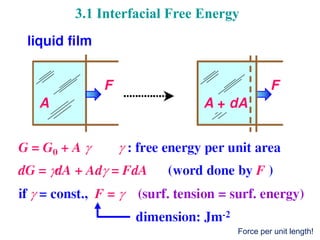

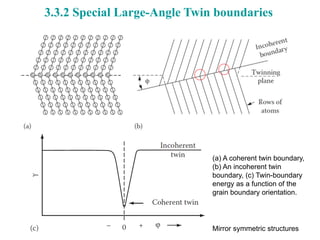

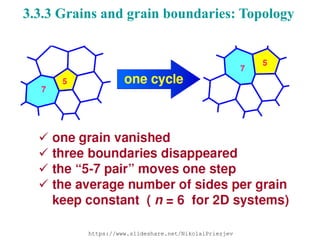

The document focuses on the phase transformations in metals and alloys, highlighting interfacial free energy, grain boundaries, and the kinetics of migration within crystal structures. It discusses various boundary types, including low-angle, high-angle, twist, and special boundaries, and their implications on microstructure and grain growth. Additionally, it covers interphase interfaces and coherency strains, providing insights into the behavior of different phases within metallic systems.