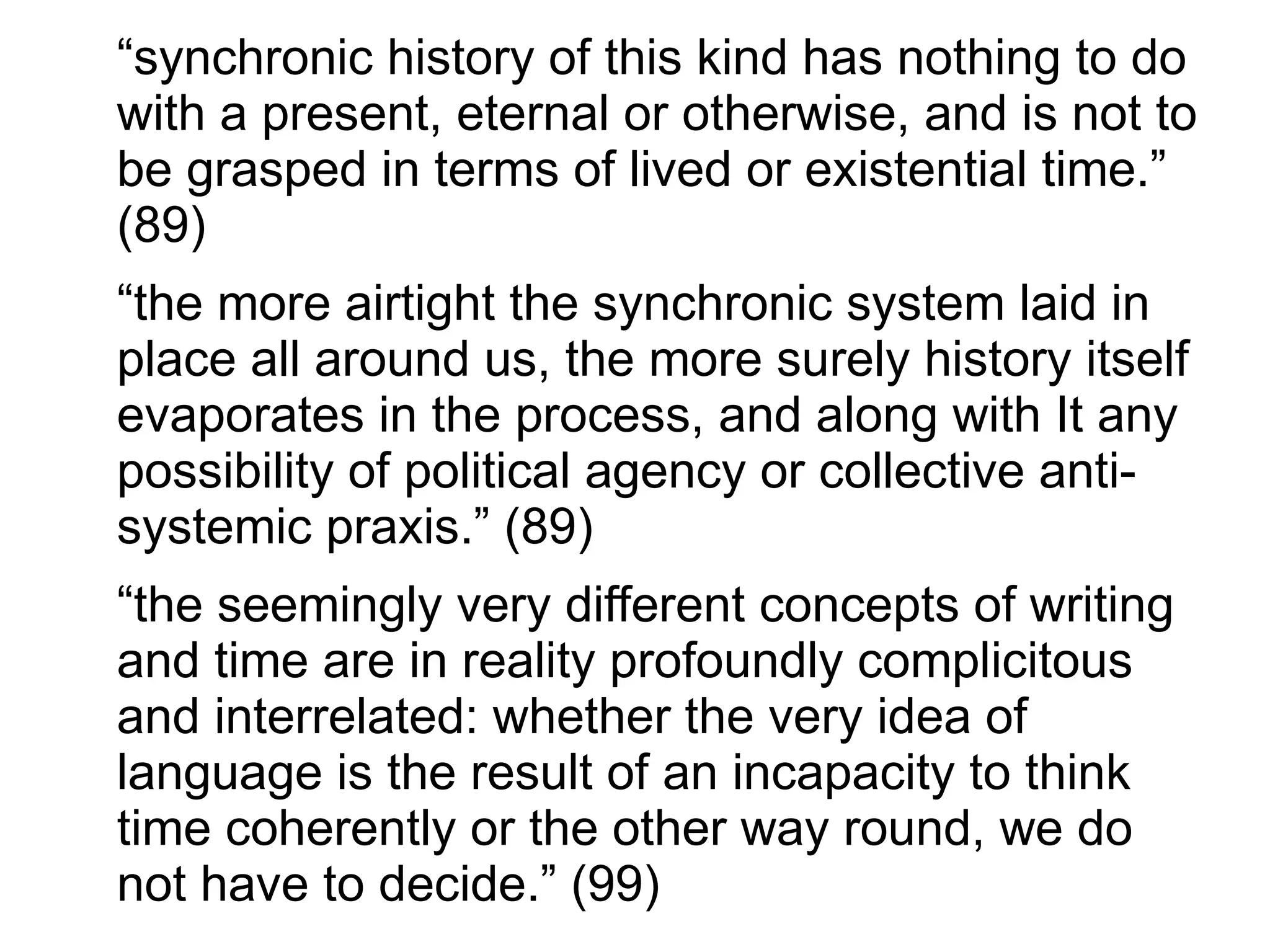

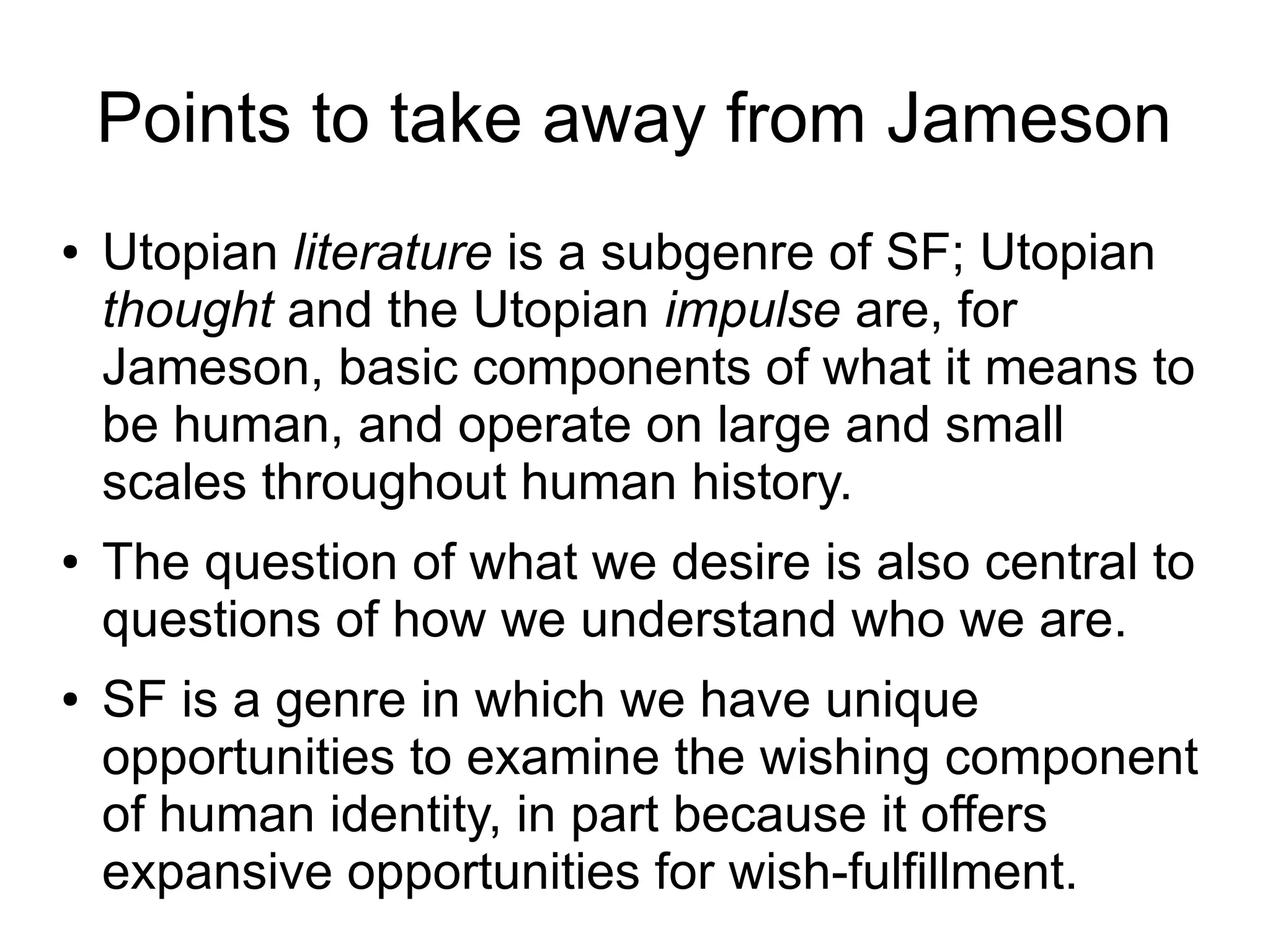

- Jameson analyzes the threat posed by understanding history solely from a synchronic perspective, which views situations statically without considering their development over time. Focusing only on structures risks naturalizing them and eliminating the possibility of change.

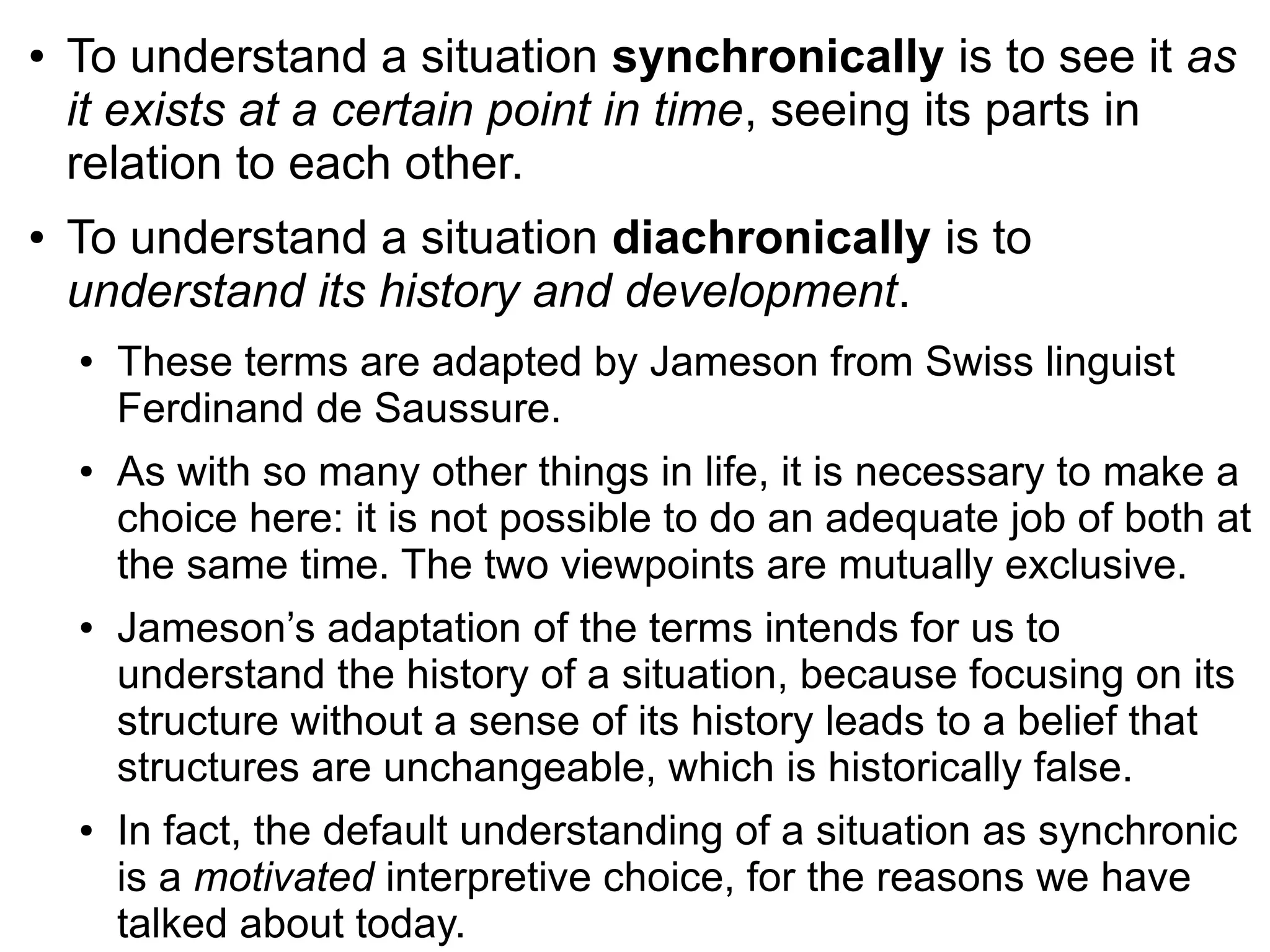

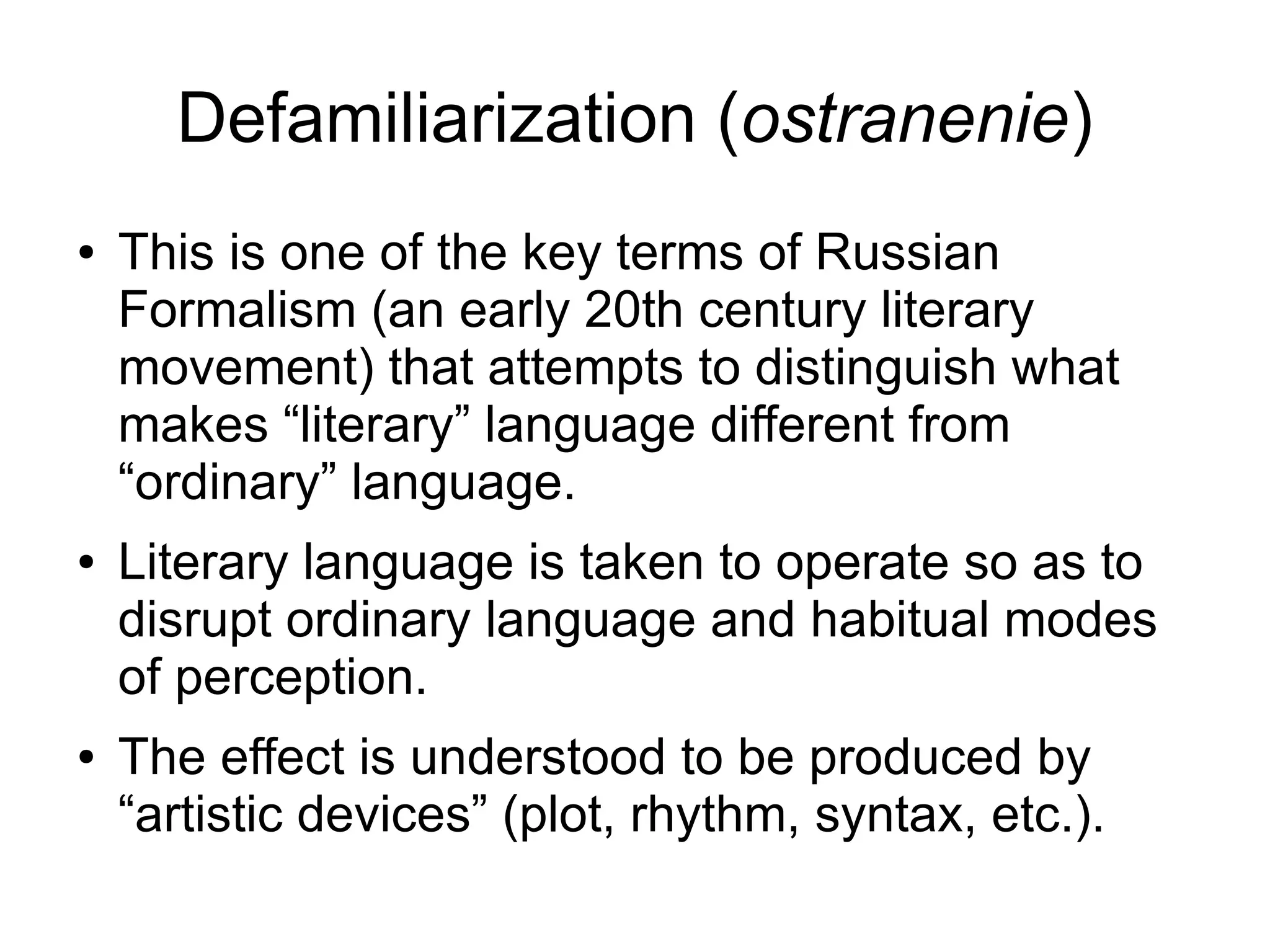

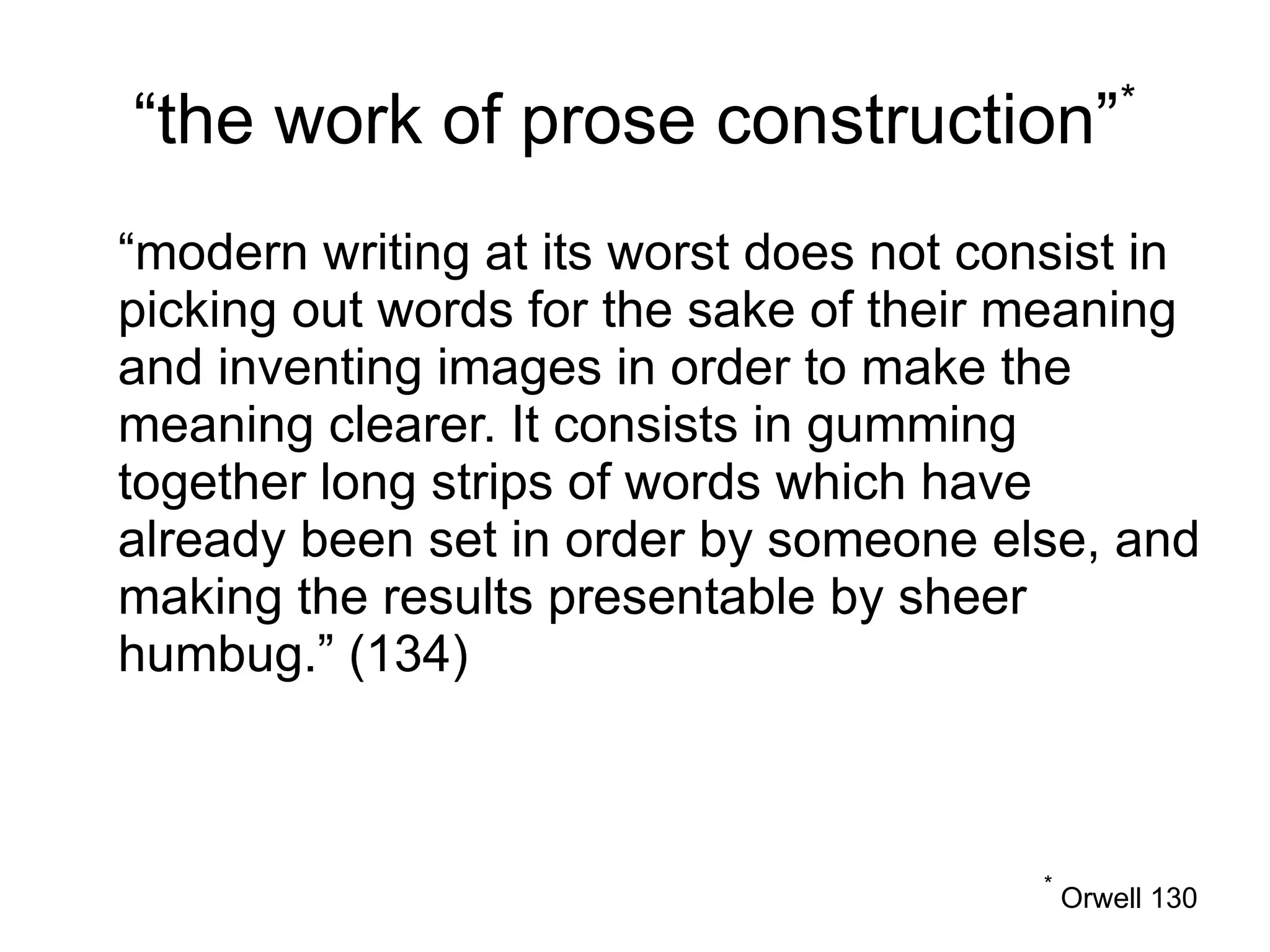

- The document discusses the concepts of defamiliarization, how habitual perceptions can be disrupted to see things in a new light, and Orwell's arguments that political language can corrupt thought and that conscious effort is needed to improve writing.

- Key terms are introduced, such as synchronic vs. diachronic perspectives, ostranenie or defamiliarization, and how concepts from different thinkers relate to questions of language, perception, and politics.

![“I think that the attack on ‘causality’ as such is

misplaced; Kant has taught us (along with many

others) that in a sense cause and causality are

mental categories, about which it makes no

sense to assert that they are either true or false.

It would be more plausible and useful to think of

causality as an essentially narrative category […]

In other words, as the number of things that

historical inquiry is willing to accept as

determinants increases – gender relations,

writing systems, weaponry – each becomes a

candidate for a new version of that ‘ultimately

determining instance’ or cause which in its turn

dictates a new historical narrative, a fresh way of

telling the story of the historical change in

question.” (87-88)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-3-2048.jpg)

![“A proliferation of narratives […] emerges which raises

the terrifying specter of postmodern relativism and which

is scarcely reduced by assigning each one its specific

sub-field and then attempting to reconstruct some new

and more ‘complex’ or ‘differentiated’ discipline as a whole

[…] From a limited series of conventional and

reassuringly simple narrative options (the so-called

master narratives), history becomes a bewildering torrent

of sheer Becoming, a stream into which, as Cratylus put it

long ago, one cannot even step once.

“It then proves reassuring to abandon these diachronic

dilemmas altogether, and to turn towards a perspective

and a way of looking at things in which they do not even

arise. Such is the realm of the synchronic, and we may

well ask ourselves what replaces narrative here and what

representational forms are available to articulate this new

systemic view of the multiple coexistence of factors or

facts.” (88-89)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-5-2048.jpg)

![“This is clearly a question that needs to be enlarged

to include Science Fiction as well, if one follows

Darko Suvin [in Metamorphoses of Science Fiction],

as I do, in believing Utopia to be a socio-economic

sub-genre of that broader literary form. Suvin’s

principle of ‘cognitive estrangement’ – an aesthetic

which, building on the Russian Formalist notion of

‘making strange’ as well as the Brechtian

Verfremdungseffekt, characterizes SF in terms of

an essentially epistemological function […] – thus

posits one specific subset of this generic category

specifically devoted to the imagination of alternative

social and economic forms.” (xiii-xiv)

Glancing back before we move on …](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-9-2048.jpg)

![“Mr. Wordsworth, on the other hand, was to […] give the

charm of novelty to things of every day, and to excite a

feeling analogous to the supernatural, by awakening the

mind's attention to the lethargy of custom, and directing it to

the loveliness and the wonders of the world before us; an

inexhaustible treasure, but for which, in consequence of the

film of familiarity and selfish solicitude, we have eyes, yet

see not, ears that hear not, and hearts that neither feel nor

understand.” (S.T. Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, 1817)

“Poetry lifts the veil from the hidden beauty of the world, and

makes familiar objects be as if they were not familiar; it

reproduces all that it represents, and the impersonations

clothed in its Elysian light stand thenceforward in the minds

of those who have once contemplated them, as memorials

of that gentle and exalted content which extends itself over

all thoughts and actions with which it coexists.” (Percy

Shelley, “A Defence of Poetry,” 1821)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-11-2048.jpg)

![“Politics and the English Language” (1946)

“Most people who bother with the matter at all

would admit that the English language is in a

bad way, but it is generally assumed that we

cannot by conscious action do anything about it.

[…] Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief

that language is a natural growth and not an

instrument which we shape for our own

purposes.” (127)

“Now, it is clear that the decline of a language

must ultimately have political and economic

causes: it is not due simply to the influence of

this or that individual writer.” (127)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-14-2048.jpg)

![“the English language […] becomes ugly and

inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the

slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us

to have foolish thoughts.” (128)

“no modern writer of the kind I am discussing—no

one capable of using phrases like ‘objective

consideration of contemporary phenomena”—would

ever tabulate his thoughts in that precise and

detailed way.” (133)

“By using stale metaphors, similes and idioms, you

save much mental effort, at the cost of leaving your

meaning vague, not only for your reader but for

yourself.” (134)

Language and Thought](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-15-2048.jpg)

![“The sole aim of a metaphor is to call up a visual

image. When these images clash—as in The Fascist

octopus has sung its swan song, the jackboot is

thrown into the melting-pot—it can be taken as certain

that the writer is not seeing a mental image of the

objects he is naming; in other words he is not really

thinking.” (134)

“When one watches some tired hack on the platform

mechanically repeating the familiar phrases […] one

often has a curious feeling that one is not watching a

live human being but some kind of dummy. […] And

this is not altogether fanciful. A speaker who uses that

kind of phraseology has gone some distance toward

turning himself into a machine. The appropriate noises

are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not

involved as it would be if he were choosing his words

for himself.” (136)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-16-2048.jpg)

![Some primary faults of bad writing

(for Orwell)

● “staleness of imagery [and] lack of precision”

(129)

● “banal statements […] given an appearance of

profundity” (131)

● “slovenliness and vagueness” (132)

● “words […] used in a consciously dishonest

way” (133)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-18-2048.jpg)

![Motivated bad writing

“In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out

of politics’. All issues are political issues, and

politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly,

hatred and schizophrenia.” (137)

“If thought corrupts language, language can also

corrupt thought. […] The debased language that I

have been discussing is in some ways very

convenient.” (137)

“one ought to recognise that the present political

chaos is connected with the decay of language,

and that one can probably bring about some

improvement by starting at the verbal end.” (139)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture10-cuibono-130830040854-phpapp02/75/Lecture-10-Cui-bono-19-2048.jpg)