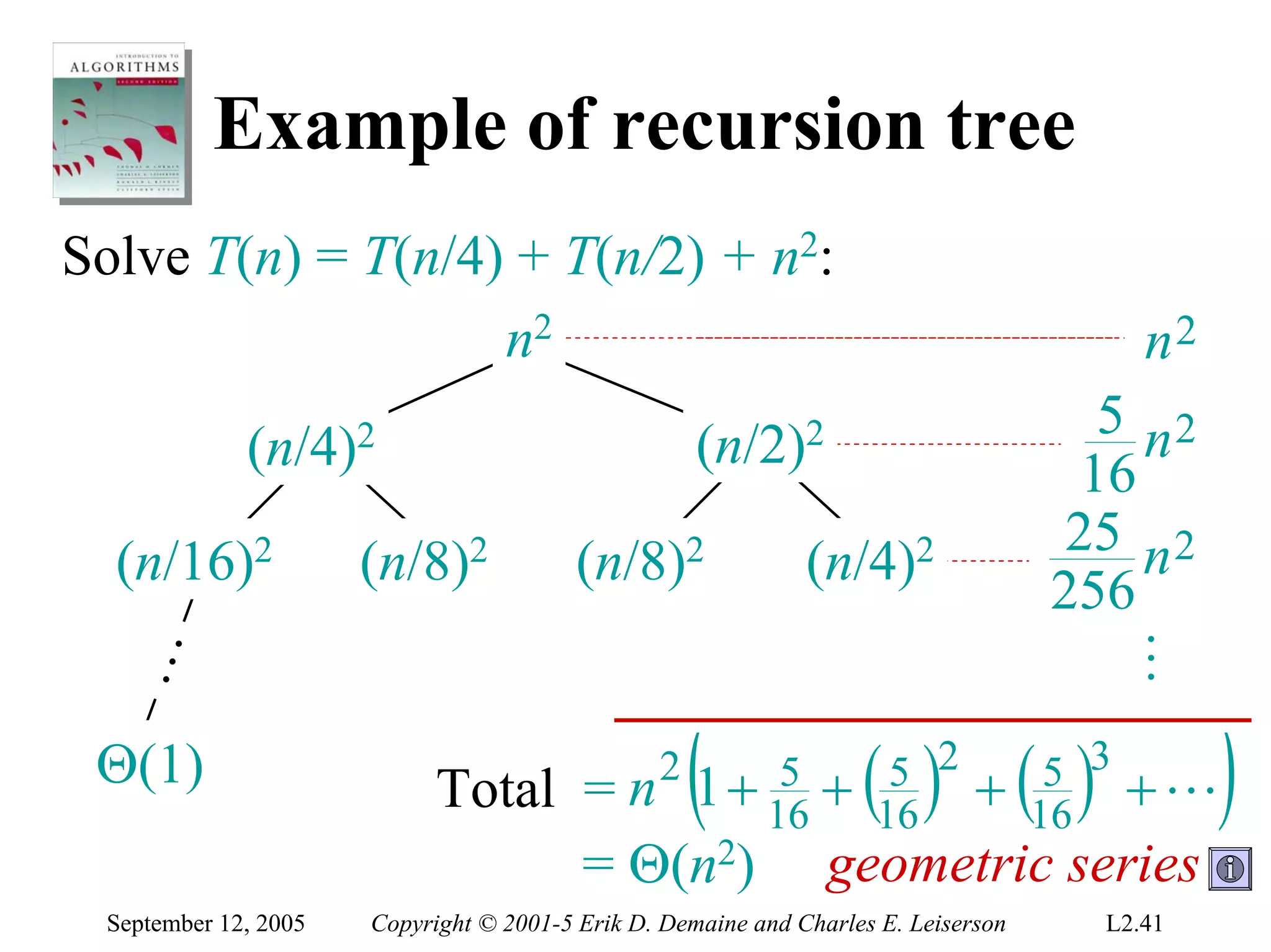

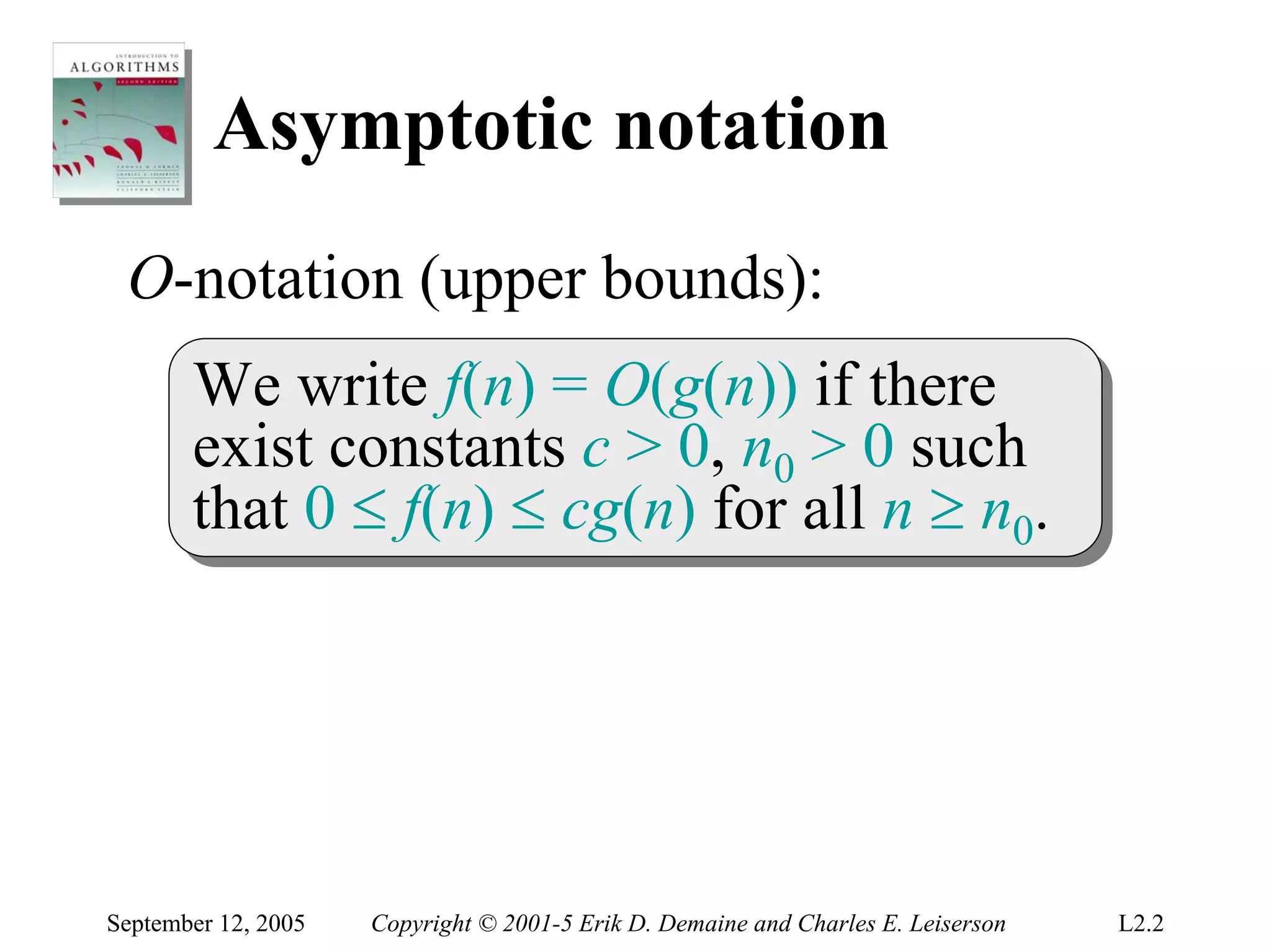

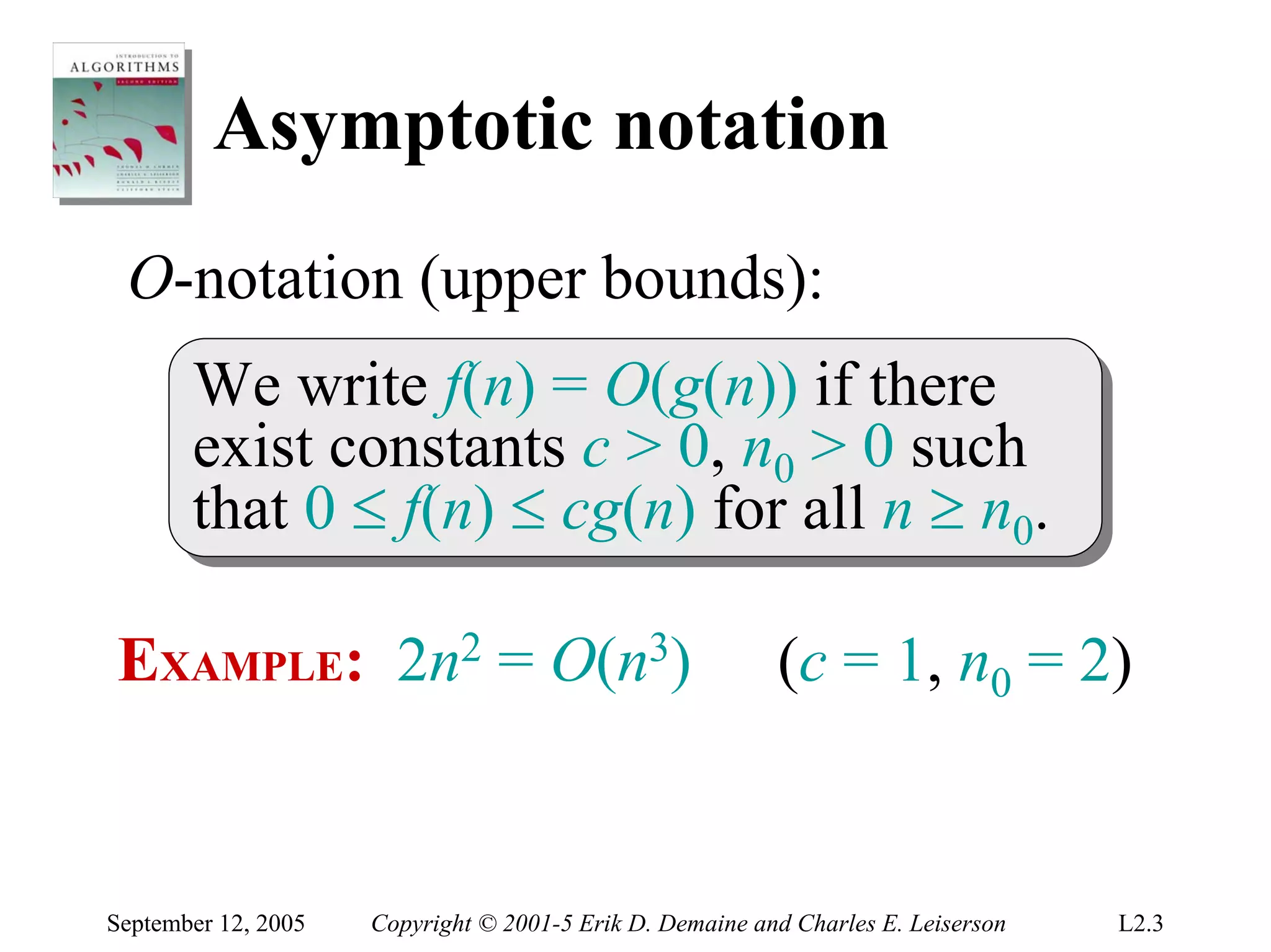

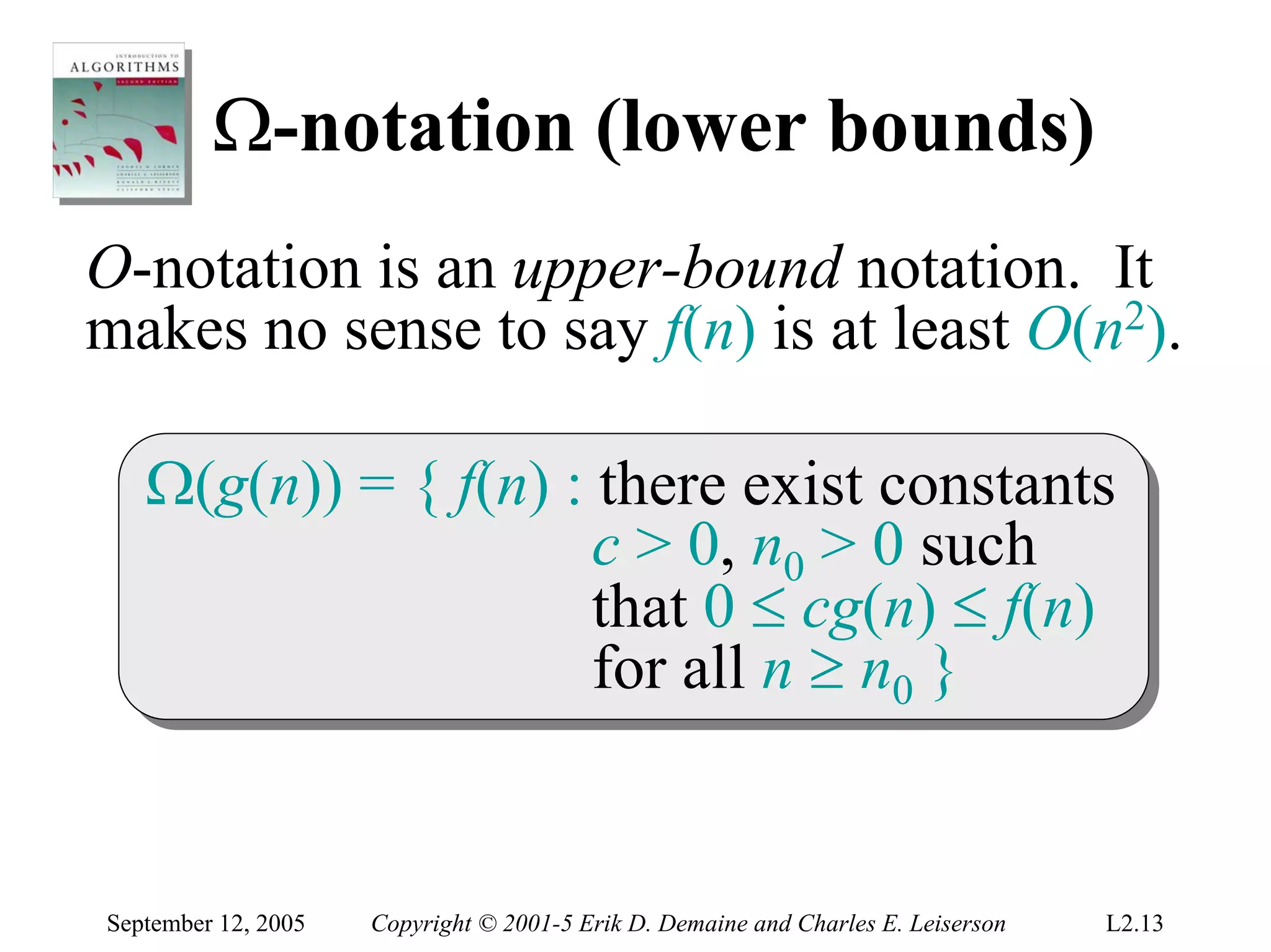

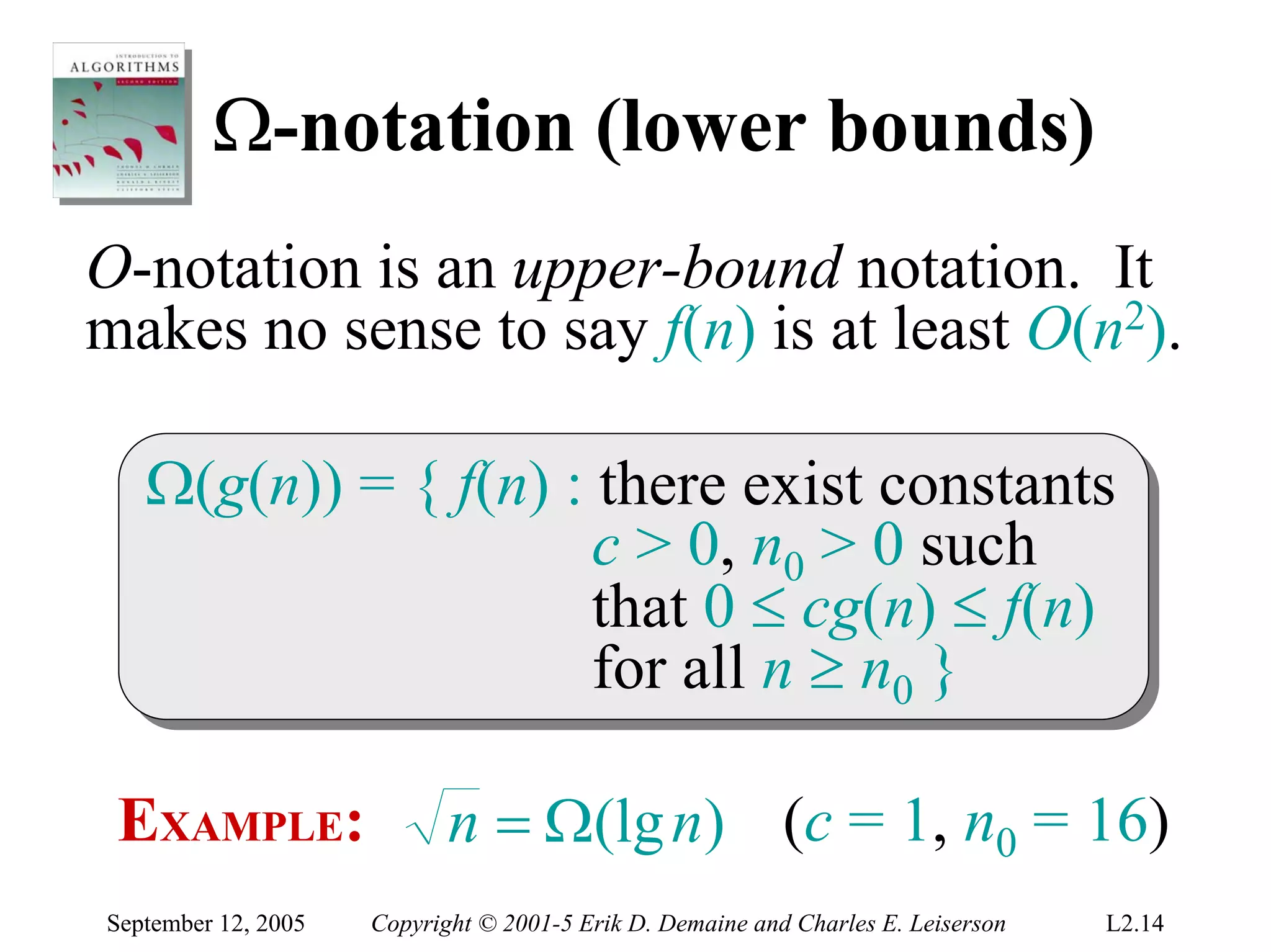

This document summarizes a lecture on asymptotic notation and techniques for solving recurrence relations. It introduces O, Ω, and Θ notation for describing asymptotic upper bounds, lower bounds, and tight bounds of functions. It also discusses methods for solving recurrence relations, including the substitution method of guessing a solution, verifying it by induction, and solving for constants. Recurrence relations are important for analyzing divide-and-conquer algorithms.

![Substitution method

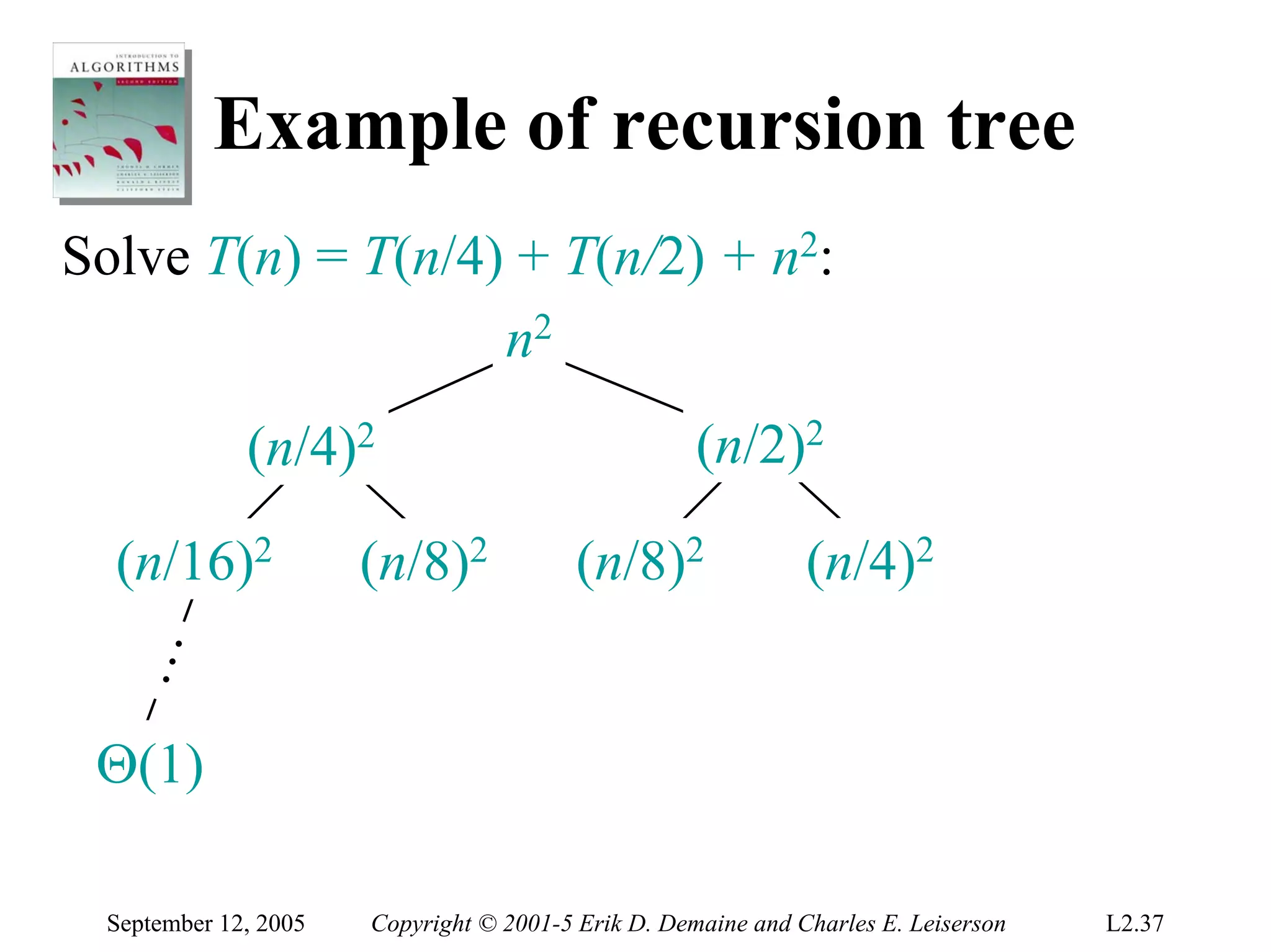

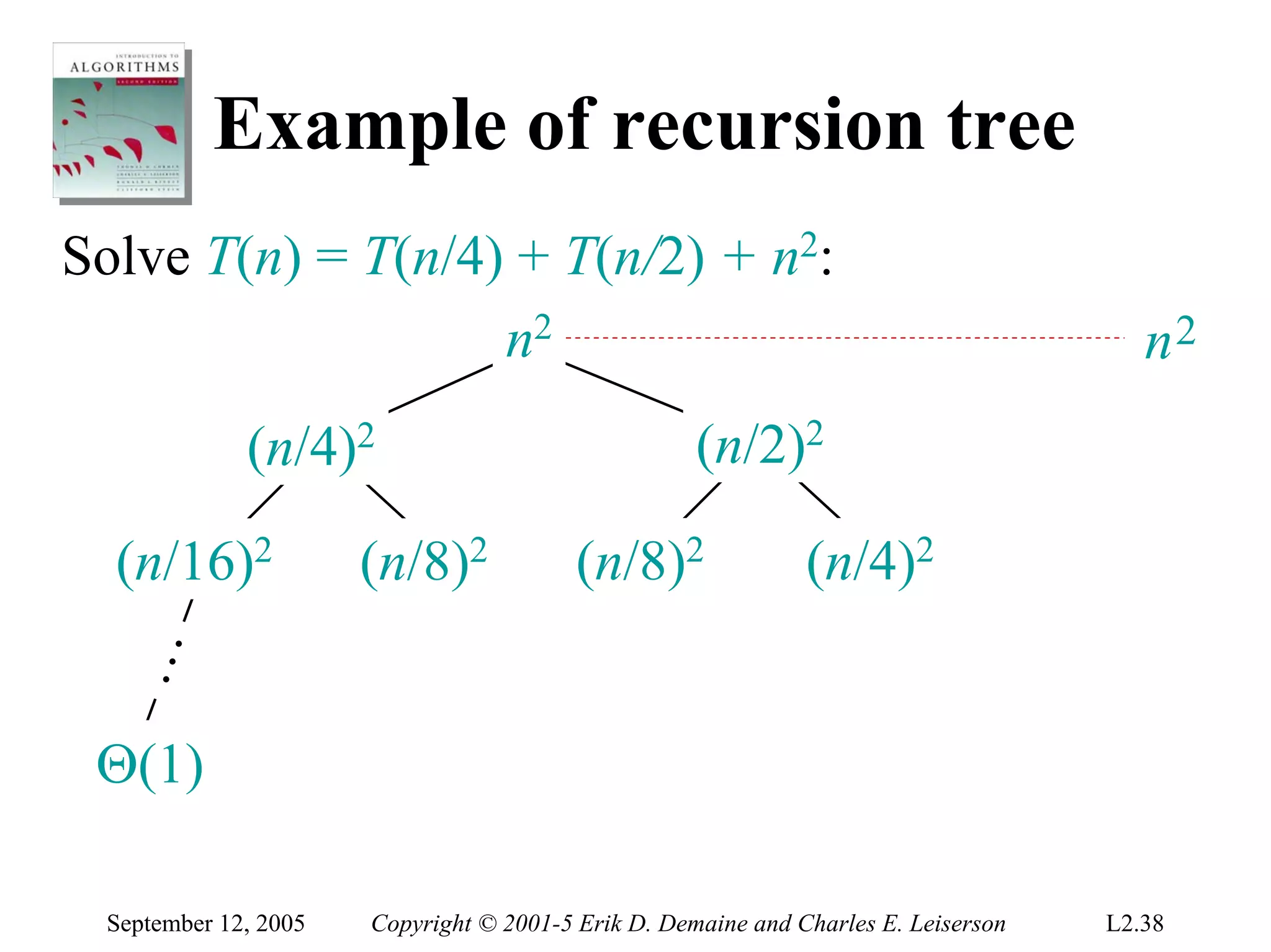

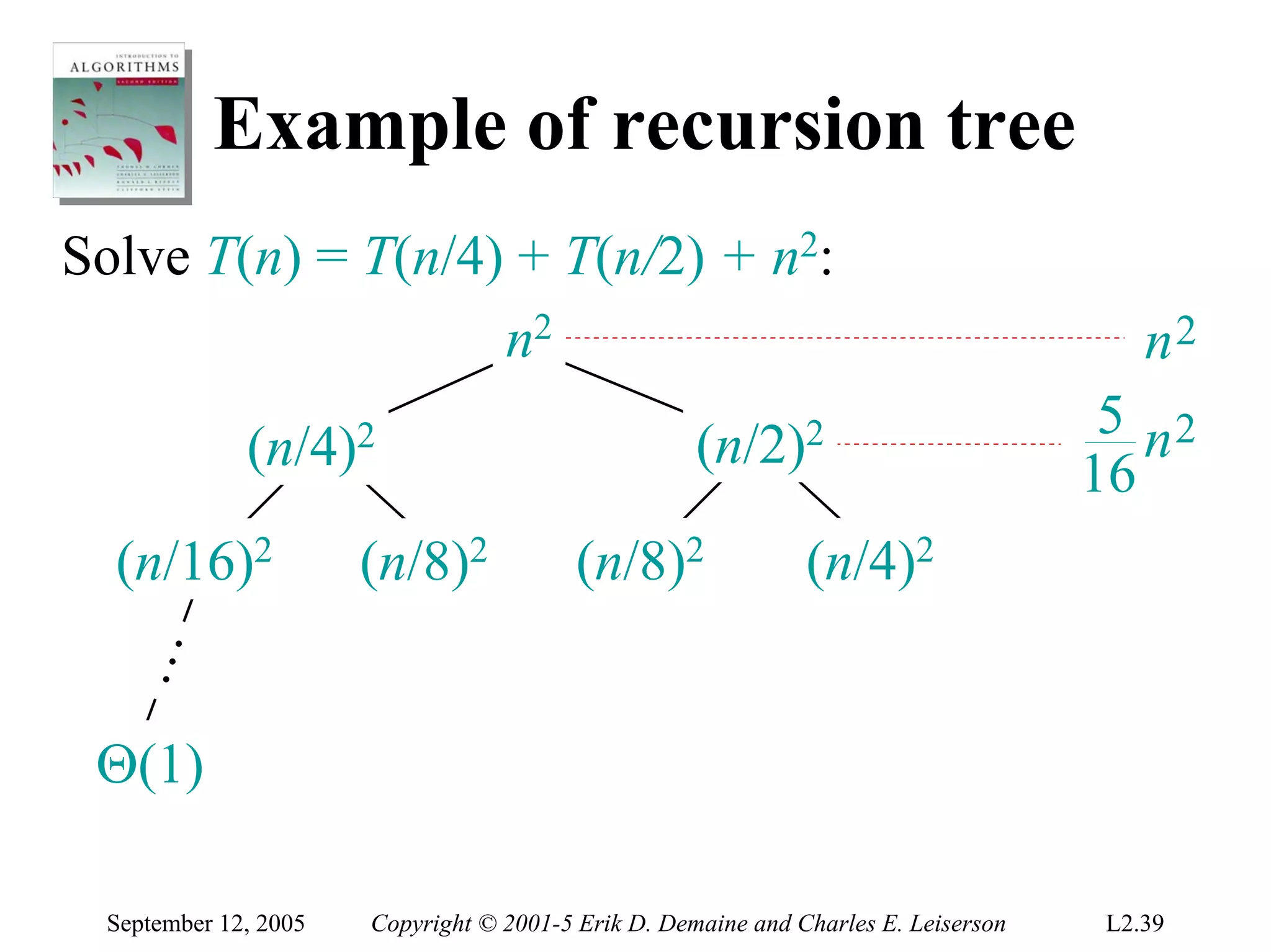

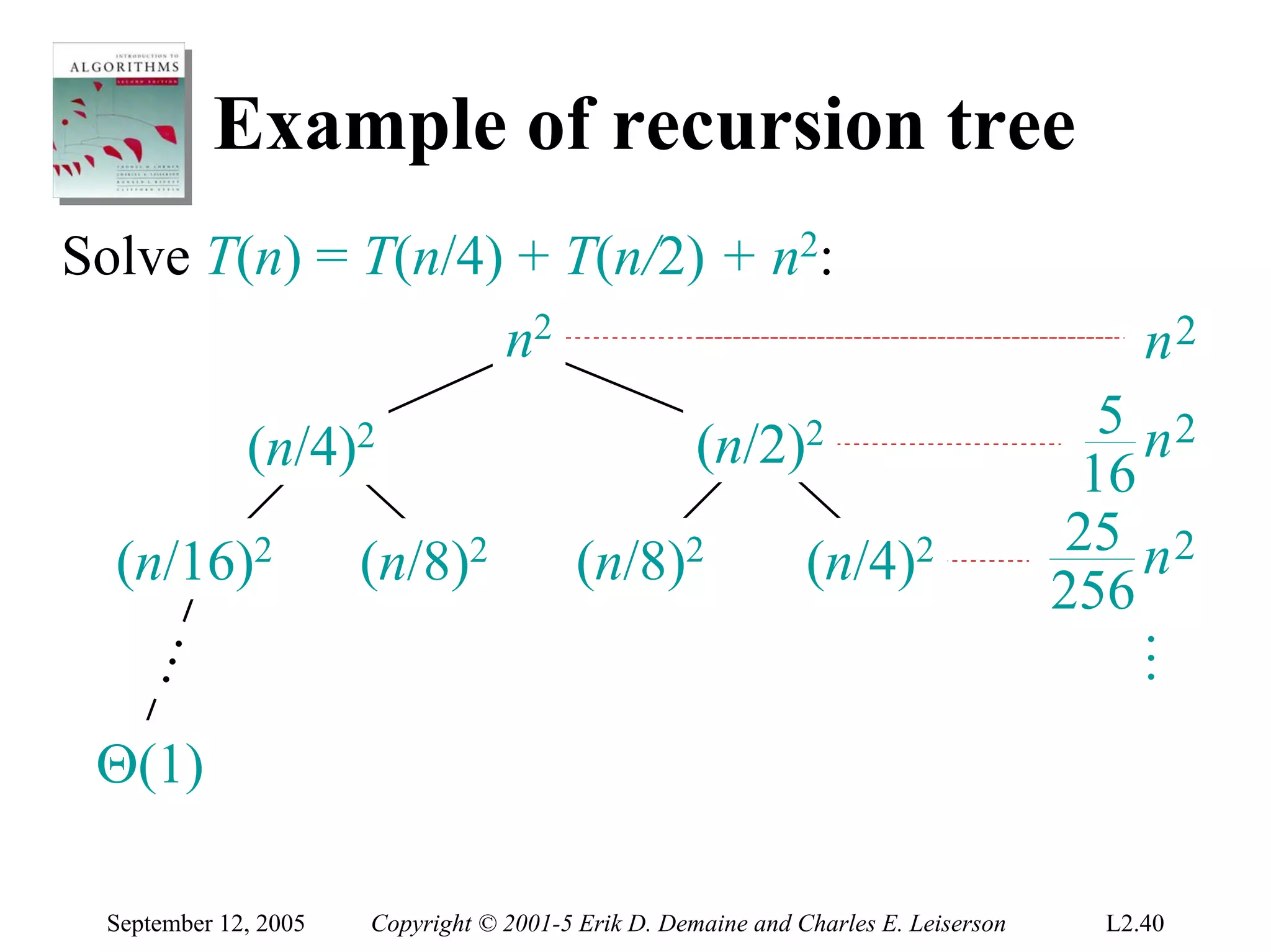

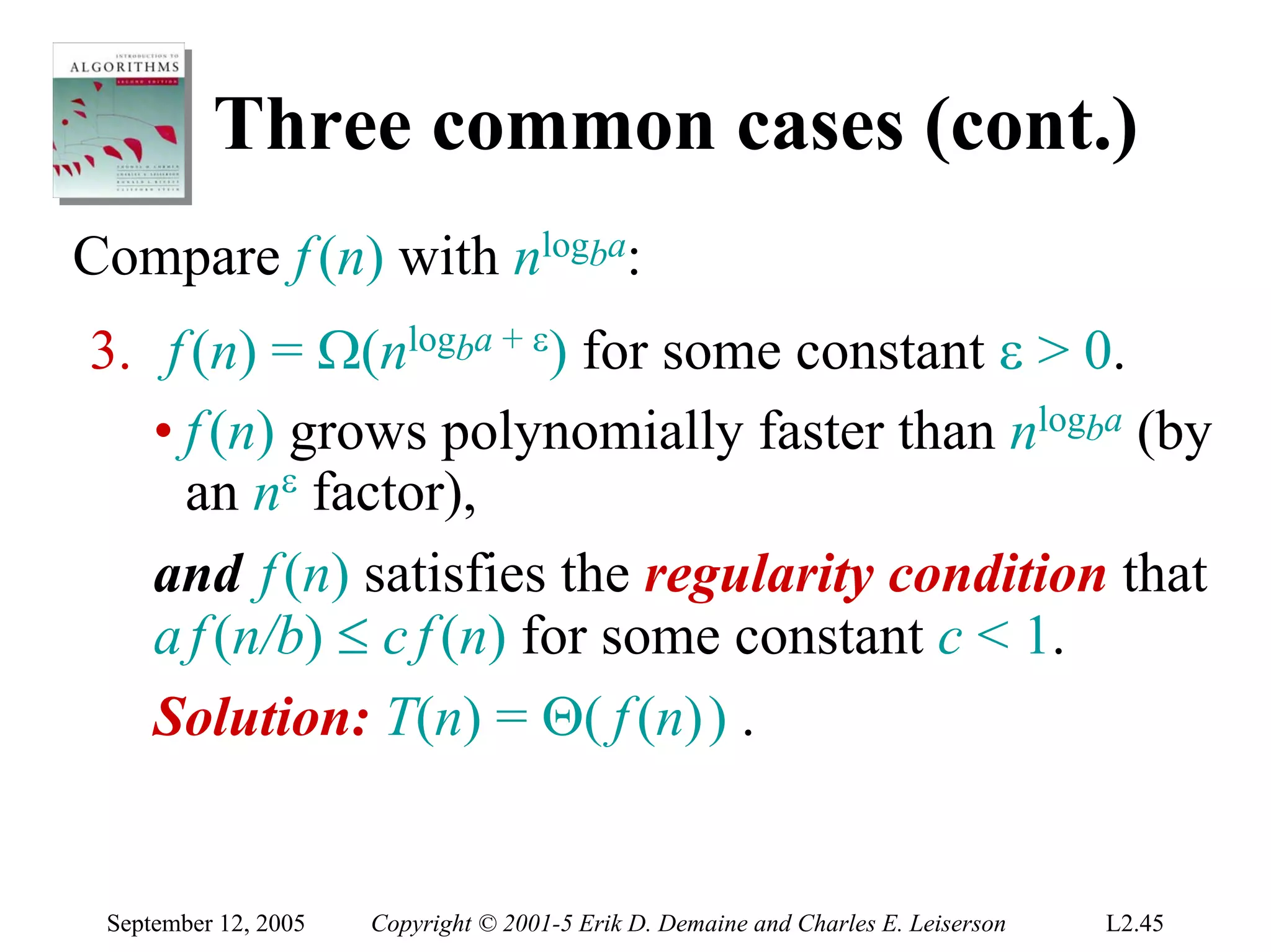

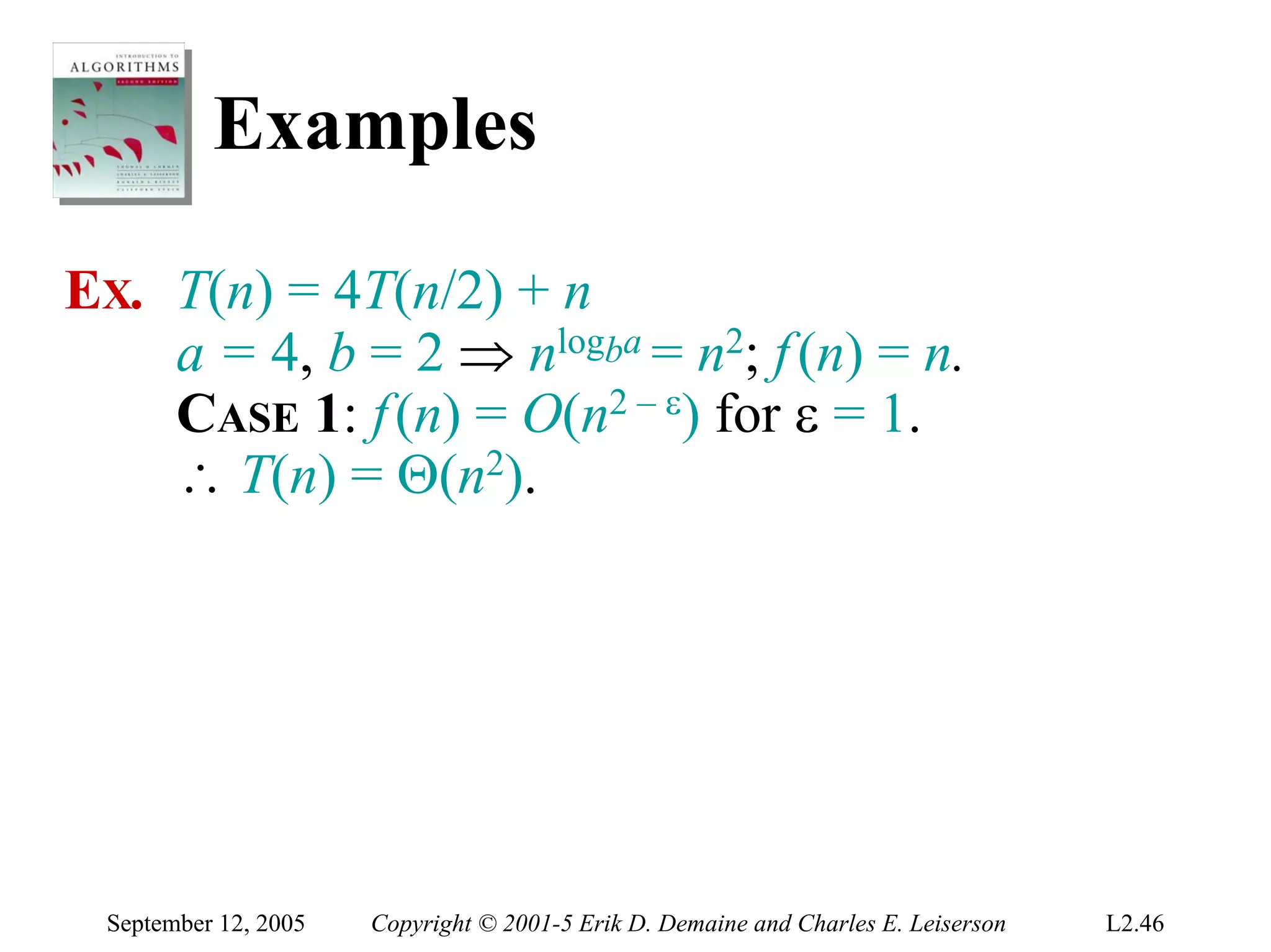

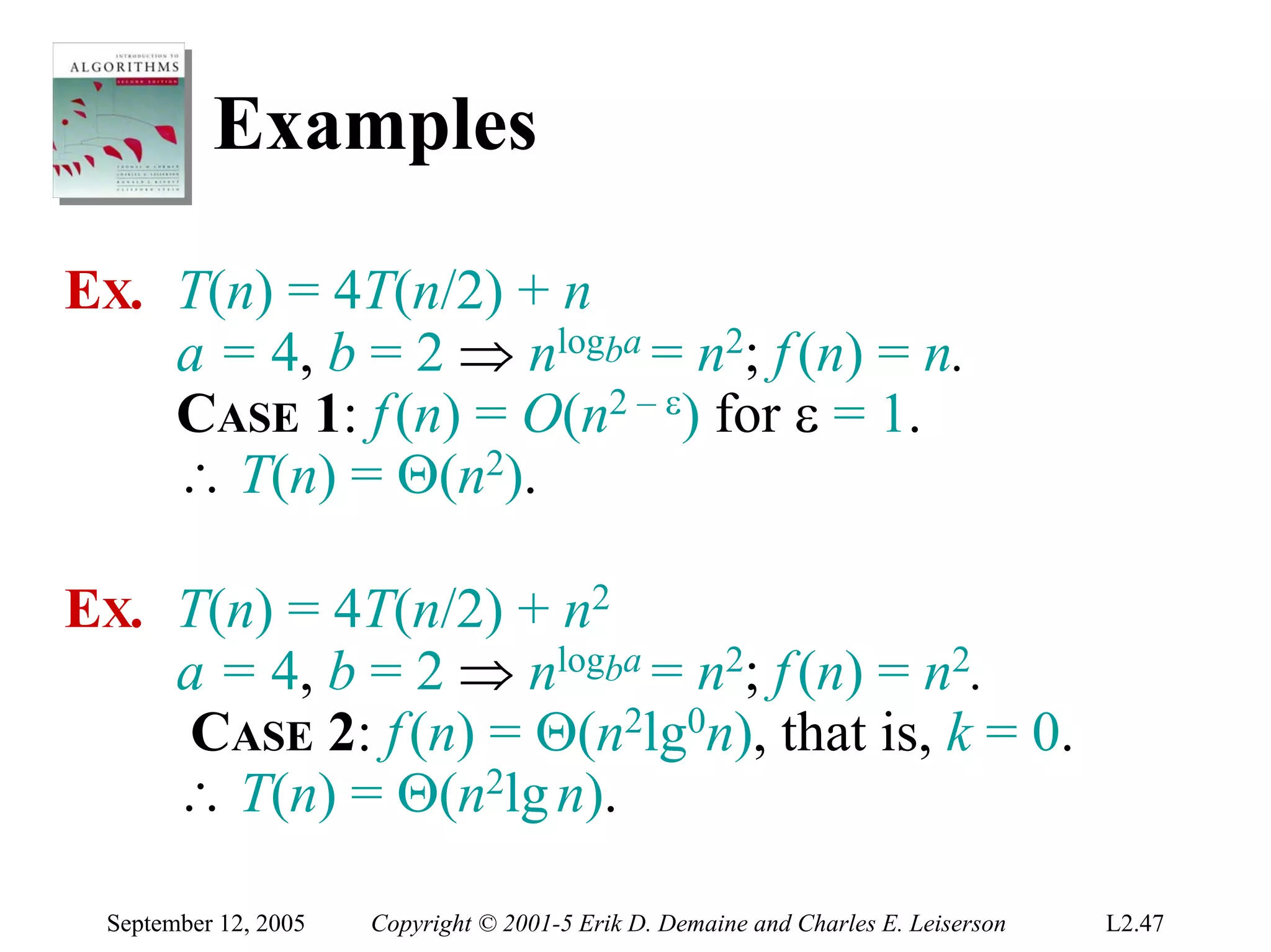

The most general method:

1. Guess the form of the solution.

2. Verify by induction.

3. Solve for constants.

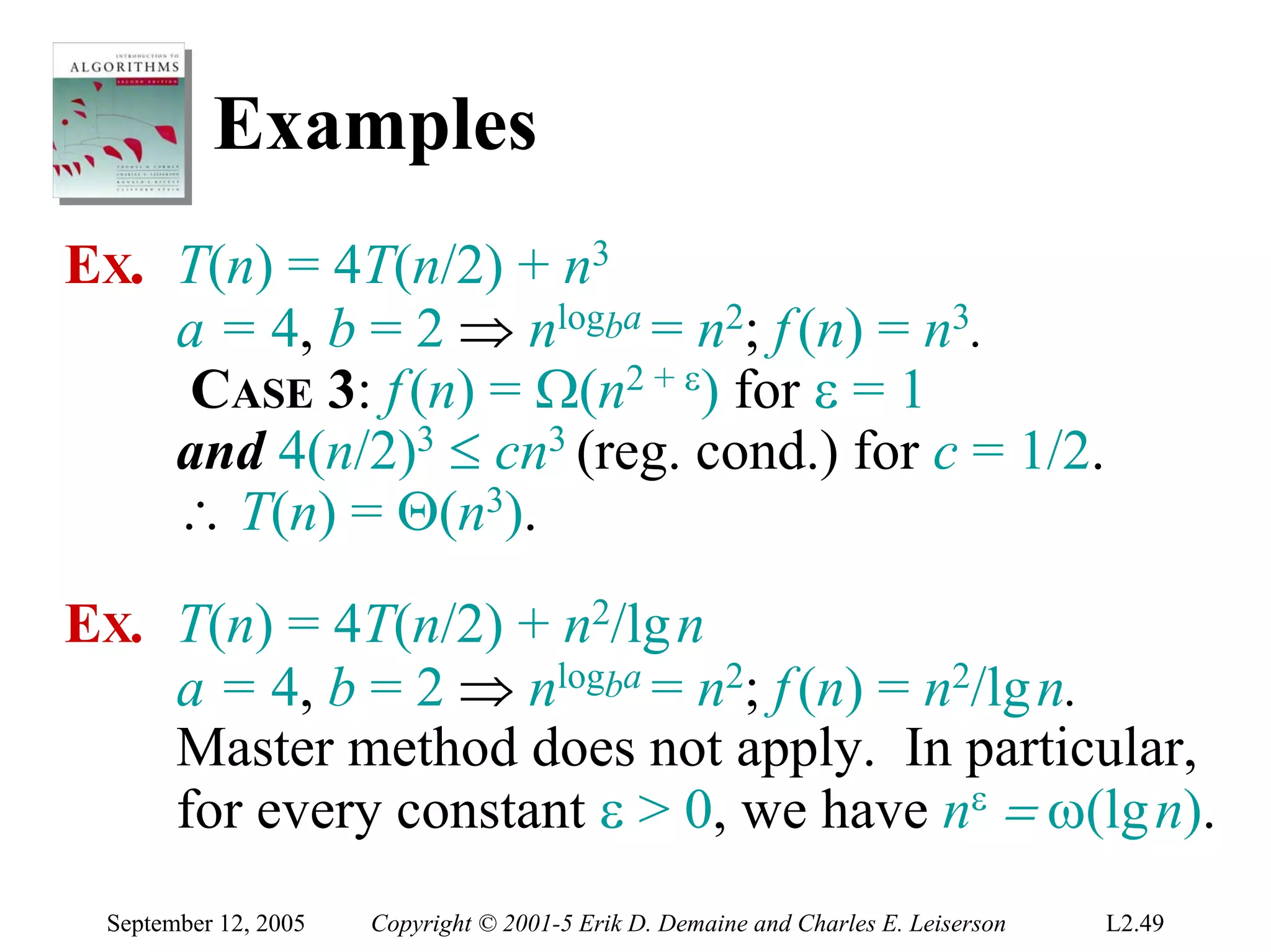

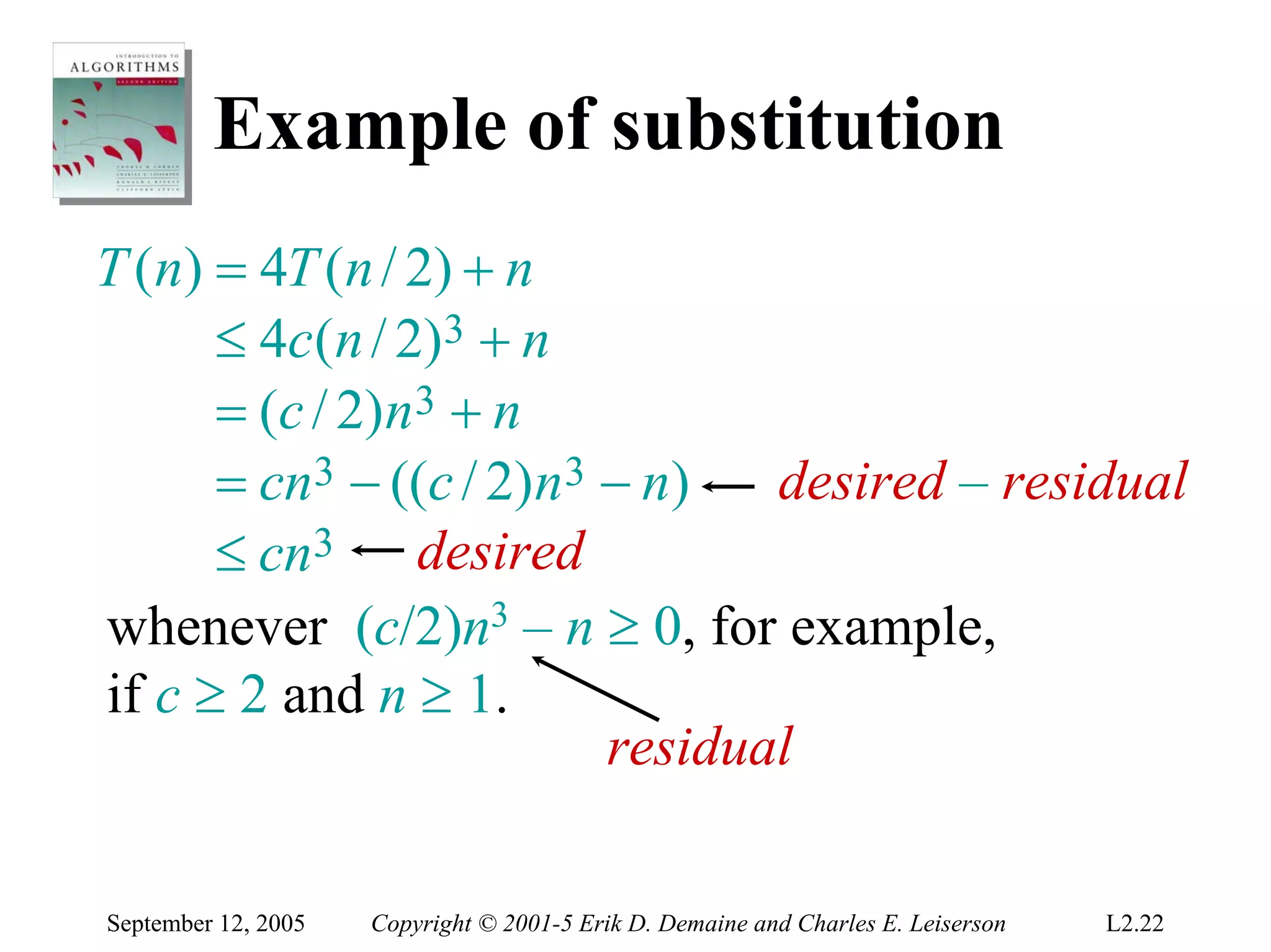

EXAMPLE: T(n) = 4T(n/2) + n

• [Assume that T(1) = Θ(1).]

• Guess O(n3) . (Prove O and Ω separately.)

• Assume that T(k) ≤ ck3 for k < n .

• Prove T(n) ≤ cn3 by induction.

September 12, 2005 Copyright © 2001-5 Erik D. Demaine and Charles E. Leiserson L2.21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2-algorth-100204074220-phpapp01/75/Lec2-Algorth-21-2048.jpg)

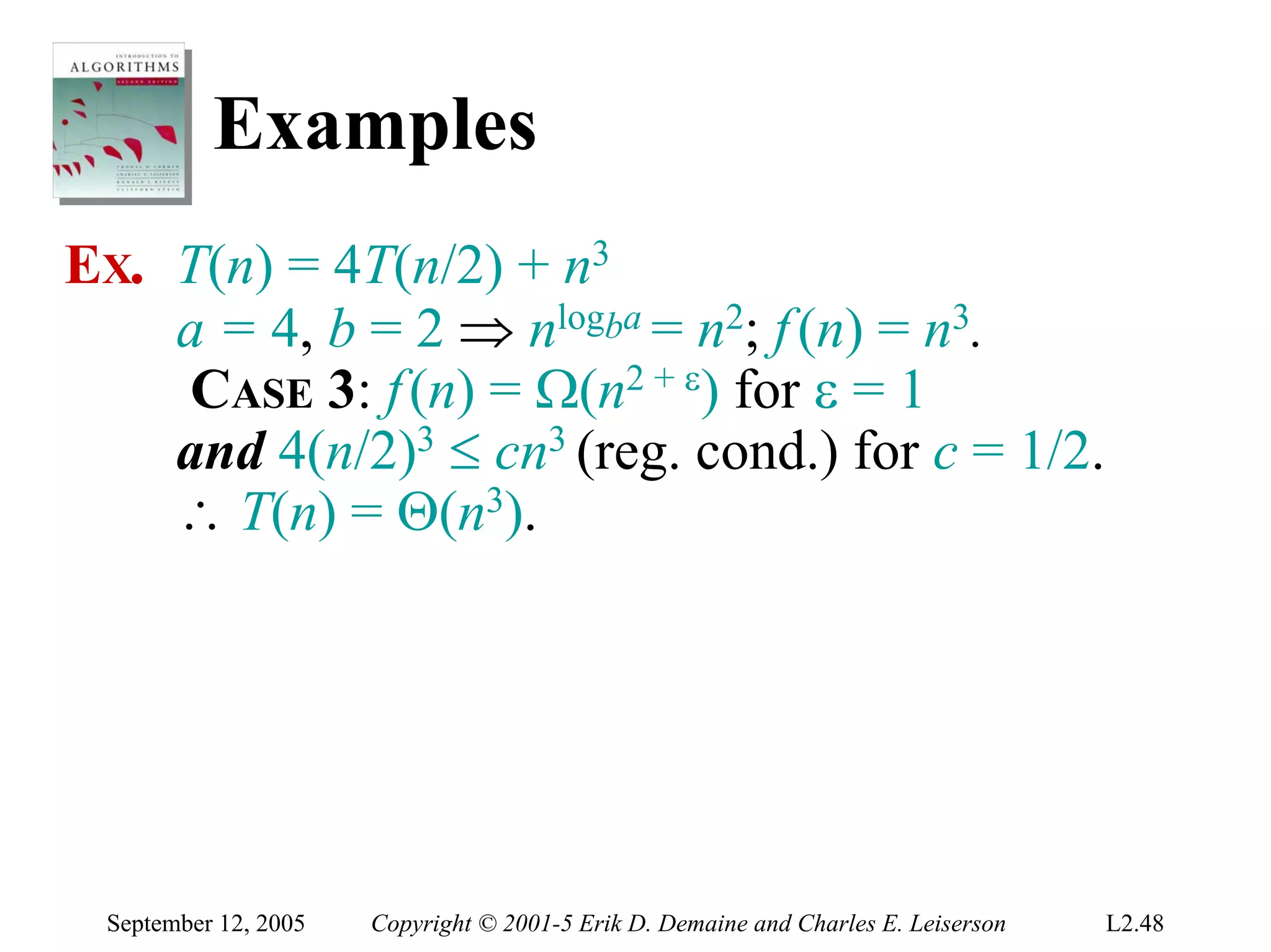

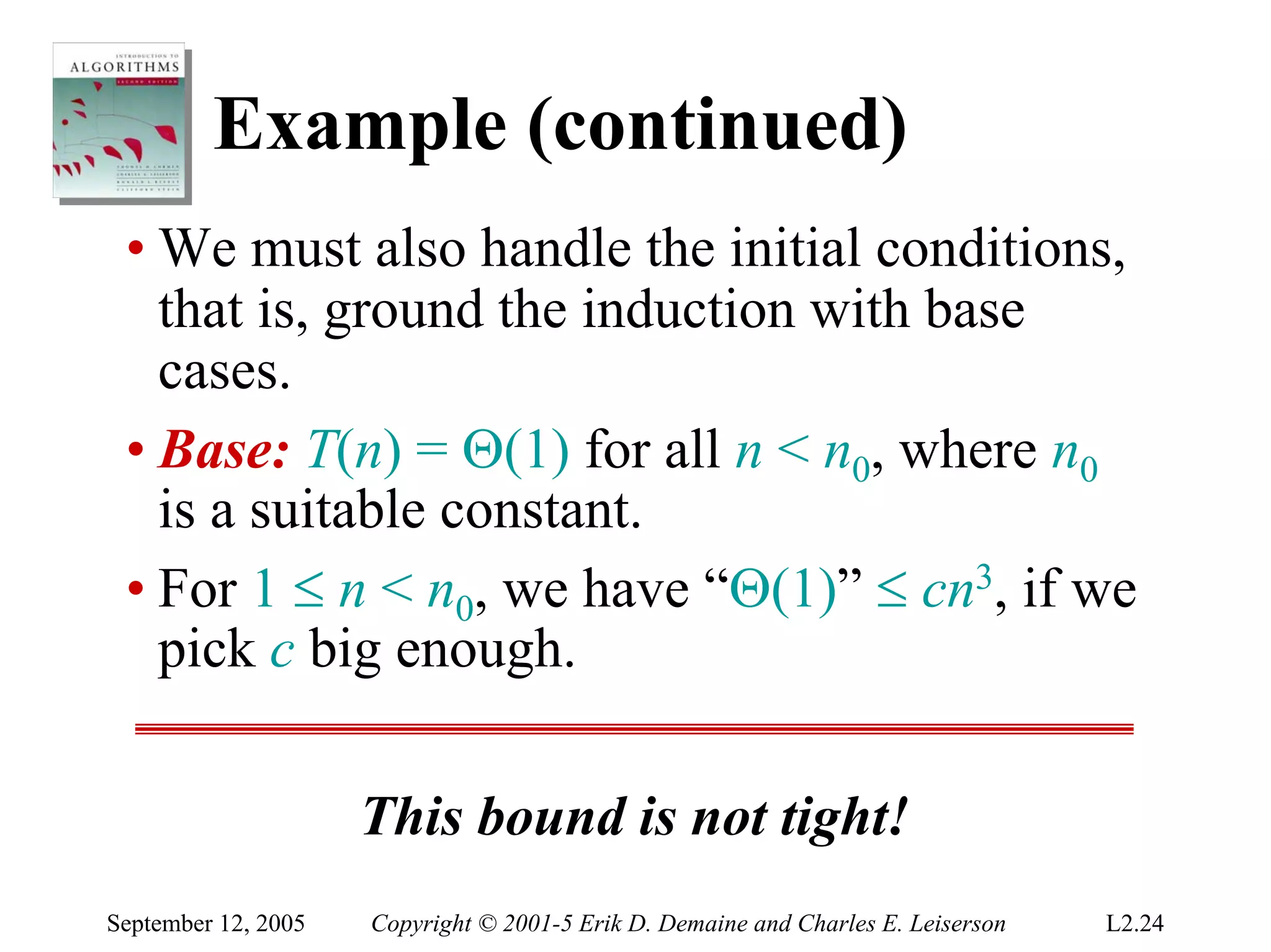

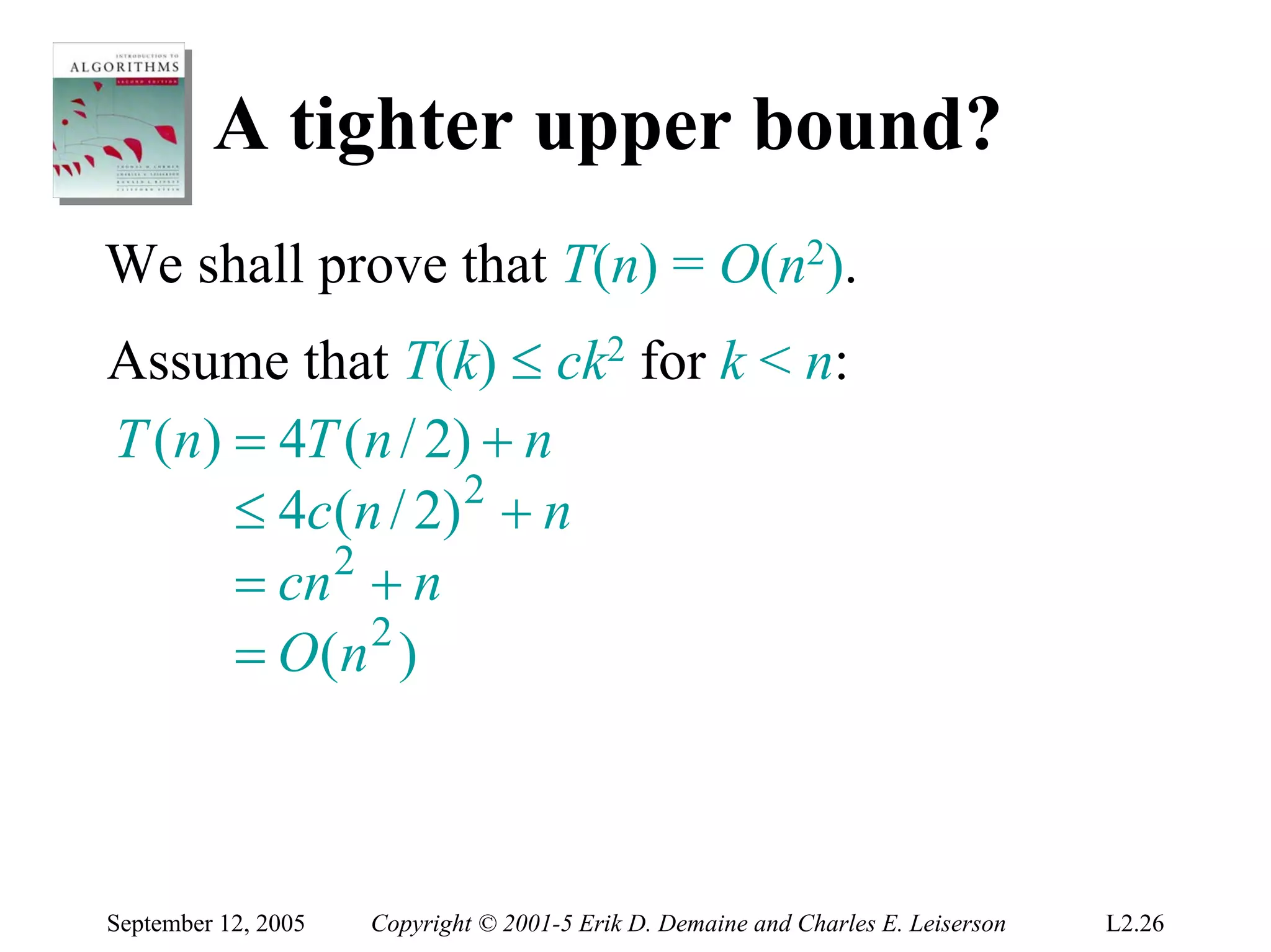

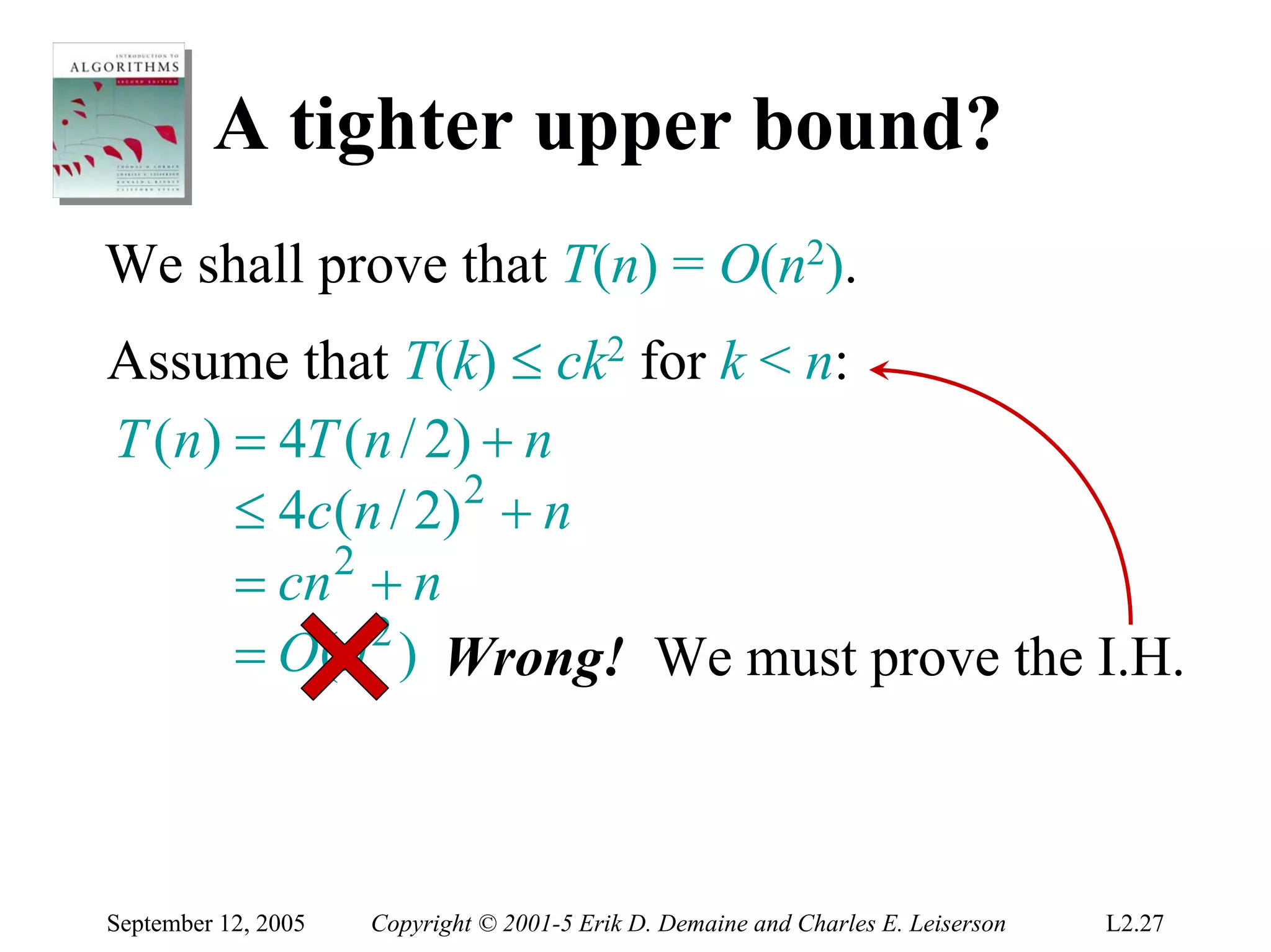

![A tighter upper bound?

We shall prove that T(n) = O(n2).

Assume that T(k) ≤ ck2 for k < n:

T (n) = 4T (n / 2) + n

≤ 4c ( n / 2) 2 + n

= cn 2 + n

= O(n 2 ) Wrong! We must prove the I.H.

= cn 2 − (− n) [ desired – residual ]

≤ cn 2 for no choice of c > 0. Lose!

September 12, 2005 Copyright © 2001-5 Erik D. Demaine and Charles E. Leiserson L2.28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lec2-algorth-100204074220-phpapp01/75/Lec2-Algorth-28-2048.jpg)