This document summarizes a presentation on pediatric headache and migraine management in the emergency department. It discusses:

1) Common differential diagnoses for pediatric headache in the ED including primary headaches like migraine and secondary headaches.

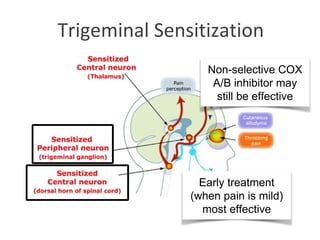

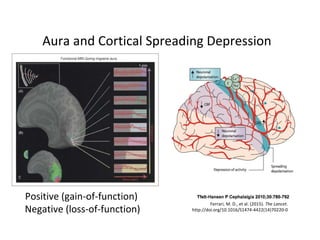

2) An overview of migraine physiology and the trigeminovascular system. Cortical spreading depression may trigger migraines by activating the trigeminovascular system.

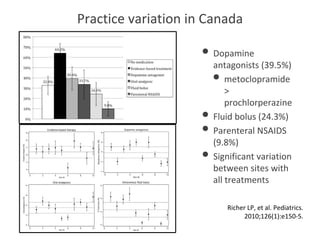

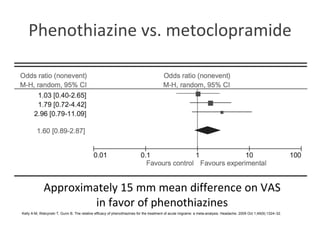

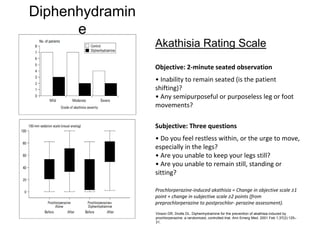

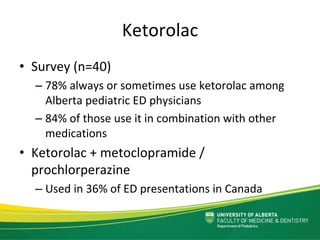

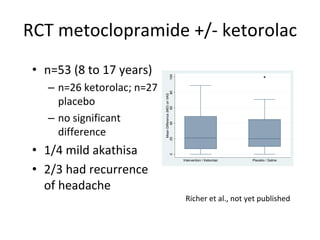

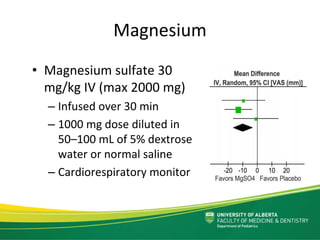

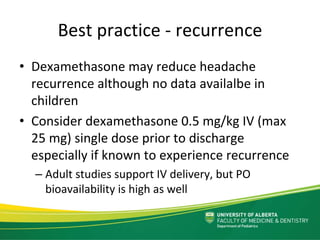

3) Current evidence and controversies around migraine treatment in the ED, including oral, nasal, and subcutaneous triptan therapies as well as novel drug targets in development. Fluid bolus therapy and dopamine antagonists are commonly used but practice varies significantly between sites.

![ACR Appropriateness Criteria for Child

with Headache

Primary Headache

• No imaging is indicated for typical

migraine.

• In ophthalmologic migraine with focal

neurologic symptoms of unilateral

ptosis or complete third‐nerve palsy,

MRI is recommended.

• MRI is also recommended for patients

with miscellaneous findings such as

vertigo, basilar artery migraine

syndrome, persistent confusion

migraine syndrome, progressive chronic

headache, or hemiplegic migraine.

• MRI should be performed for patients

with seizures and postictal headaches.

Secondary Headache

• If neurologic signs or symptoms of increased

intracranial pressure are present, MRI is

recommended. If MRI is not available or

there are problems with sedation, CT should

be performed.

• CT of the head without intravenous contrast

is recommended for sudden severe

headaches (thunderclap headaches).

• If subarachnoid hemorrhage is detected, CT

or conventional angiography should be

performed. MRA is also appropriate but is

generally considered less sensitive in

detecting small aneurysms.

• If intracranial hemorrhage is present, MRI of

the brain should be performed if possible.

Obtaining a concomitant MRA is

recommended.

Hayes LL, Coley BD, Karmazyn B et al. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Headache—child.

Reston (VA): ACR [Internet]. 2012[cited 2015 Jun 25]; 8. Available from: https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69439/Narrative/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-151109134702-lva1-app6891/85/La-migraine-16-320.jpg)

![Appropriateness Rating

Category

N Imaged % Important

Abnormalities

Incidental

Abnormalities

Usually not appropriate 72 4 6% 0 1

May be appropriate 13 8 61% 1 1

Usually appropriate 10 8 80% 1 3

Imaging Audit

- 95 patient visits sampled

- Diagnosis: headache in 35, migraine in 53, meningeal infection

in 1, neoplasm with hydrocephalus in 1, metabolic disease in 1

and other non-relevant conditions in 4

- 4 patients imaged did not meet any appropriateness criteria,

but each had prior neurosurgery

Hayes LL, Coley BD, Karmazyn B et al. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Headache—child.

Reston (VA): ACR [Internet]. 2012[cited 2015 Jun 25]; 8. Available from: https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69439/Narrative/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dr-151109134702-lva1-app6891/85/La-migraine-18-320.jpg)