The document discusses headache disorders, with a focus on migraines, highlighting their prevalence, etiology, and clinical management. It details types of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, their effectiveness, and potential side effects, emphasizing the importance of individualized treatment. Additionally, it outlines the role of various medications, including triptans and beta-adrenergic antagonists, in both acute management and prophylactic therapy for migraine sufferers.

![Introduction [2]

All clinicians should be familiar with:

The various types of headache,

Clinical indicators suggesting the need for urgent medical

attention and

Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic options for

treatment

The International Headache Society (IHS) classifies

primary headaches as:

Migraine,

Tension-type,

Cluster and Other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias

2/3/2023

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-3-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [2]

Gender differences in migraine prevalence have been

linked to menustration ,

However, these differences persist beyond menopause.

Prevalence is highest in both men and women between

the ages of 30 and 49 years.

The usual age of onset is 12 to 17 years of age for

females and 5 to 11 years for males.

About 93% of those with migraine reported some

headache-related disability,

2/3/2023

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-5-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [3]

And 54% were severely disabled or needed bed rest

during an attack

A number of neurologic and psychiatric disorders as

well as CVD show increased comorbidity with migraine.

Whether this relationship is causal or representative of

a common pathophysiologic mechanism is unknown.

The economic burden of migraine is substantial;

The indirect costs from work-related disability far

exceed the direct costs associated with treatment.

2/3/2023

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-6-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [4]

Etiology and Pathophysiology

“Vascular hypothesis,” it was thought that focal

neurologic symptoms preceding or accompanying the

headache were caused by vasoconstriction and

reduction in cerebral blood flow.

The headache was thought to be caused by a

compensatory vasodilation with displacement of pain

sensitive intracranial structures.

Although blood flow is decreased during the aura of

migraine, other observations do not support the vascular

hypothesis

2/3/2023

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-7-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [5]

Negative neuroimaging evidence for such vascular

changes and

The effectiveness of medications with no vascular

properties make this contention untenable.

A neuronal etiology has emerged as the leading

mechanism for the development of migraine pain.

More recent evidence suggests that the pain of migraine

is generated centrally

2/3/2023

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-8-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [5]

Which involves episodic dysfunction of neural

structures that control the cranial circulation (the

trigeminovascular system)

This area may represent an endogenous “migraine

generator.”

Sporadic dysfunction of the nociceptive system and the

neural control of cerebral blood flow is hypothesized

These trigger migraine headache via their effects on

the trigeminovascular system

2/3/2023

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-9-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [5]

It is believed that depressed neuronal electrical activity

spreads across the brain,

This produce transitory neural dysfunction.

Headache pain is likely due to compensatory

overactivity in the trigeminovascular system of the brain.

Activation of trigeminal sensory nerves leads to the

release of vasoactive neuropeptides :

Eg, calcitonin gene-related peptide, neurokininA,

substance P

These produce inflammatory response around vascular

structures in the brain, provoking the sensation of pain

2/3/2023

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-10-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [5]

Continued sensitization of CNS sensory neurons can

potentiate and intensify headache pain as an attack

progresses.

Bioamine pathways projecting from the brainstem

regulate activity within the trigeminovascular system.

The pathogenesis of migraine is most likely due to an

imbalance in the modulation of nociception and blood

vessel tone by serotonergic and noradrenergic neurons

2/3/2023

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-11-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [6]

Abnormalities in serotonin (5-HT) activity are also thought to

play a role in migraine headache.

Plasma 5-HT levels decrease by nearly half during a

migraine attack,

And a corresponding rise in the urinary excretion of 5-

hydroxyindoleacetic acid, the primary metabolite of 5-HT.

Also, reserpine, a drug that depletes 5-HT from body stores,

has been found to induce a stereotypical headache in

migraineurs and

It induce a dull discomfort in patients not prone to migraine

2/3/2023

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-12-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [7]

In summary, the pathophysiology of migraine probably

involves dysfunction of the trigeminal neurons that

provide sensory innervation and modulate blood flow to

intracranial blood vessels.

The endogenous stimulus causing this dysfunction may

arise from a “migraine generator” in the brainstem.

Disturbances in 5-HT activity are also probably involved

It is this feature that serves as the target for many

migraine-specific therapies

2/3/2023

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-13-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [8]

Clinical presentation

General

Migraine is a common, recurrent, severe headache that

interferes with normal functioning.

Symptoms

Migraine is characterized by:

Recurring episodes of throbbing head pain,

Frequently unilateral, with gradual onset

when untreated can last from 4 to 72 hours.

2/3/2023

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-14-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [9]

IHS Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine

Migraine without aura

At least five attacks

Headache attack lasts 4-72 hours (untreated or

unsuccessfully treated)

Headache has at least two of the following

characteristics:

Unilateral location

Pulsating quality

Moderate or severe intensity

Aggravation by or avoidance of routine physical activity

2/3/2023

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-15-320.jpg)

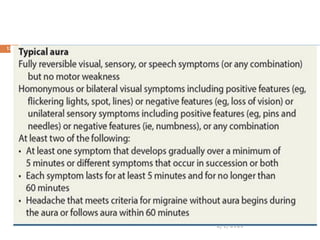

![Migraine headache [10]

During headache at least one of the following:

Nausea, vomiting, or both

Photophobia and phonophobia

Not attributed to another disorder

Migraine with aura (classic migraine)

At least two attacks

Migraine aura fulfills criteria for typical aura, hemiplegic

migraine, retinal migraine or brainstem aura

Not attributed to another disorder

2/3/2023

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-16-320.jpg)

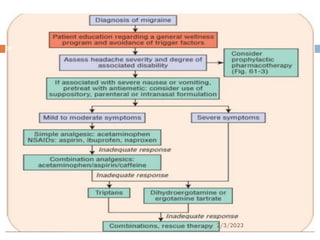

![Migraine headache [11]

Treatment

Desired Outcome

Treat migraine attacks rapidly and consistently without

recurrence

Restore the patient’s ability to function

Minimize the use of backup and rescue medications

Optimize self-care for overall management

Be cost-effective in overall management

Cause minimal or no adverse effects

2/3/2023

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-18-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [12]

Non-pharmacologic therapy of acute migraine

headache is limited but can include:

application of ice to the head and periods of rest or sleep,

usually in a dark, quiet environment.

Preventive management of migraine should begin with the

identification and avoidance of factors that consistently

provoke migraine attacks in

Behavioral interventions, such as relaxation therapy, and

cognitive therapy, are preventive treatment options for

patients who prefer nondrug therapy

2/3/2023

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-19-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [13]

Commonly Reported Triggers of Migraine

Food triggers : Alcohol Caffeine/caffeine withdrawal

Chocolate Fermented and pickled foods

Environmental triggers: Glare or flickering lights

High altitude, Loud noises ,Strong smells and fumes ,Tobacco

smoke

Behavioral–physiologic triggers: Excess or insufficient sleep,

Fatigue, Menstruation, menopause

2/3/2023

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-20-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [14]

Non opiate analgesics

Simple analgesics and NSAIDs are effective

medications for the management of many migraine

attacks

They offer a reasonable first-line choice for

treatment of mild to moderate migraine attacks or

Severe attacks that have been responsive in the past

to similar NSAIDs or nonopiate analgesics.

2/3/2023

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-21-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [15]

Of the NSAIDs, aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen sodium,

tolfenamic acid, and the combination of acetaminophen plus

aspirin and caffeine have demonstrated the most consistent

evidence of efficacy.

Evidence for other NSAIDs is either limited or inconsistent.

Metoclopramide can speed the absorption of analgesics and

alleviate migraine-related nausea and vomiting.

NSAIDs should be avoided or used cautiously in patients with

previous ulcer disease, renal disease, or hypersensitivity to

aspirin.

Acetaminophen alone is not generally recommended for

migraine because the scientific support is not optimal

2/3/2023

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-22-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [16]

Opiate Analgesics

Narcotic analgesic drugs (e.g., meperidine,

butorphanol, oxycodone, and hydromorphone) are

effective

But generally should be reserved for patients with:

moderate to severe infrequent headaches in whom

conventional therapies are contraindicated

or as "rescue medication" after patients have failed to

respond to conventional therapies.

2/3/2023

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-23-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [17]

Corticosteroids

Can be considered as rescue therapy for status migrainous

Status migrainous is severe, continuous migraine that can

last up to 1 week.

Intravenous or intramuscular dexamethasone at a dose of

10 to 25 mg has also been used as an adjunct to abortive

therapy

2/3/2023

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-24-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [18]

Ergot Alkaloids and Derivatives

Ergotamine tartrate ,dihydroergotamine

Can be considered for the treatment of moderate to

severe migraine attacks

Are nonselective 5-HT1 receptor agonists

Constrict intracranial blood vessels

Then inhibit the development of neurogenic inflammation in

the trigeminovascular system

2/3/2023

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-25-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [19]

Ergotamine tartrate is available for oral, sublingual,

and rectal administration.

Oral and rectal preparations contain caffeine to

enhance absorption and potentiate analgesia.

Ergotamine use is limited because of issues of efficacy

and side effects.

Dihydroergotamine is available for intranasal and

parenteral administration.

Mixing with 1% or 2% lidocaine can reduce burning at

the injection site.

2/3/2023

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-26-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [20]

Nausea and vomiting

Resulting from stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone

Are among most common adverse effects of the ergotamine

derivatives.

Pretreatment with an antiemetic agent should be considered

Other common side effects include:

Abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, paresthesias,

muscle pain, diarrhea, and chest tightness.

Rarely but severe Side effects:

Symptoms of severe peripheral ischemia (ergotism),

2/3/2023

27](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-27-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [21]

Ergotamine derivatives are contraindicated in patients:

Renal or hepatic failure;

Coronary, cerebral, or peripheral vascular disease;

Uncontrolled hypertension; and sepsis; and

In pregnant or nursing women

2/3/2023

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-28-320.jpg)

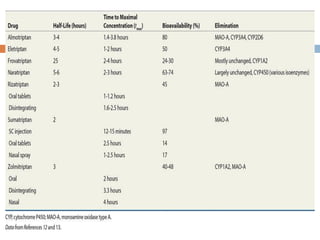

![Migraine headache [22]

Serotonin Receptor Agonists (Triptans)

Introduction of the serotonin receptor agonists, or

triptans, represented a significant advance in migraine

pharmacotherapy.

The first member of this class, sumatriptan, and

The second-generation agents zolmitriptan,

naratriptan, rizatriptan, almotriptan, frovatriptan, and

eletriptan

2/3/2023

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-29-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [22]

Are selective agonists of the 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors.

The triptans are appropriate first-line therapy for patients

with mild to severe migraine

And are used for rescue therapy when nonspecific

medications are ineffective.

Selection of a triptan is based on characteristics of the

headache, convenience of dosing,

At all marketed doses, the oral triptans are effective and

well tolerated.

The triptans differ in their pharmacokinetic and

pharmacodynamic profiles

2/3/2023

30](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-30-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [23]

In general, triptans can be divided into:

faster onset and higher efficacy and slower onset and low

efficacy

Triptans like frovatriptan and naratriptan have the longest

half lives, the slowest onset of action, and less headache

recurrence.

This may make them more suitable for patients who have

migraine attacks of a slow onset and longer duration

Faster-acting triptans are more efficacious when a rapid

onset is necessary.

Subcutaneous, intranasal, or orally dissolving tablets may be

useful in patients with prominent early nausea or vomiting .

2/3/2023

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-32-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [24]

Side effects to the triptans are common but usually mild

to moderate in nature and of short duration.

Adverse effects are consistent among the class and

include

paresthesias, fatigue, dizziness, flushing,

warm sensations, and somnolence.

One forth of patients receiving a triptan consistently

report “triptan sensations,”

These include: tightness, pressure, heaviness, or pain in

the chest, neck, or throat.

2/3/2023

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-33-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [24]

The triptans are contraindicated in patients with:

History of ischemic heart disease

Uncontrolled hypertension

cerebrovascular disease

hemiplegic and basilar migraine

Should not be used routinely in pregnancy.

The triptans should not be given within 24 hours of the

ergotamine derivatives.

MAOIs use is not recommended with in 2 weeks of triptans

therapy

Concomitant use of SSRI may result in Serotonin syndrome

2/3/2023

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-34-320.jpg)

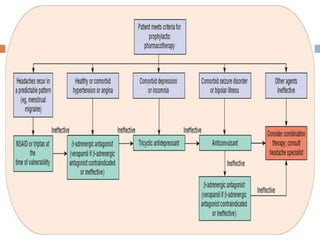

![Migraine headache [25]

Prophylactic drug therapy

Preventive migraine therapies are administered on a

daily basis to reduce the frequency, severity, and

duration of attacks

Preventive therapy should be considered in the setting

of:

Recurring migraines that produce significant disability

despite acute therapy;

Frequent attacks occurring more than twice per week with

the risk of developing medication-overuse headache;

2/3/2023

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-36-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [26]

Symptomatic therapies that are ineffective or

contraindicated, or produce serious side effects

patient preference to limit the number of attacks

Preventive therapy also may be administered preemptively

or intermittently when headaches recur in a predictable

pattern

The evidence to support the various agents used for

migraine prophylaxis has recently been reviewed

2/3/2023

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-37-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [27]

Beta -Adrenergic Antagonists

are among the most widely used drugs for migraine

prophylaxis.

drugs Propranolol, nadolol, timolol, atenolol, and metoprolol

They have proven efficacy in controlled clinical trials,

reducing the frequency of attacks by 50% in 60% to 80% of

patients

Selection of a -blocker can be based on -selectivity,

convenience of the formulation, and tolerability.

Can be considered in healthy or hypertension or angina

comorbidity

Used cautiously in : CHF, PVD, Asthma, DM

2/3/2023

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-38-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [28]

Antidepressants

Amitriptyline, the most widely studied antidepressant for

migraine prophylaxis,

Has demonstrated efficacy in placebo-controlled and

comparative studies.

Use of other antidepressants is based primarily on clinical

and anecdotal experience

Especially in comorbid depression

2/3/2023

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-39-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [29]

Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsant medications have emerged as important

therapeutic options for migraine prophylaxis with

valproate, divalproex, topiramate, and gabapentin all

demonstrating efficacy.

Anticonvulsants are particularly useful in migraineurs with

comorbid seizures, anxiety disorder, or manic-depressive

illness.

2/3/2023

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-40-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [29]

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

Are modestly effective for reducing the frequency, severity, and

duration of migraine attacks,

But potential GI and renal toxicity limit the daily or prolonged use

of these agents.

Consequently, NSAIDs have been used intermittently to prevent

headaches that recur in a predictable pattern, such as menstrual

migraine.

Administration of NSAIDs in the perimenstrual period can be

beneficial in women with true menstrual migraine.

NSAIDs should be initiated up to 1 week prior to the expected

onset of headache and continued for no more than 10 days.

2/3/2023

41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-41-320.jpg)

![Migraine headache [30]

Calcium Channel Blockers

The calcium channel blockers generally are considered

second or third-line options for preventive treatment

Used when other drugs with established clinical benefit are

ineffective or contraindicated.

Verapamil is the most widely used calcium channel blocker

for preventive treatment,

2/3/2023

42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-42-320.jpg)

![Tension–type headache [2]

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of pain in CTT headache is thought to

originate from myofascial factors and peripheral

sensitization of nociceptors.

Central mechanisms also are involved, with heightened

sensitivity of pain pathways in the CNS

The following may be initiating stimulus:

Mental stress, nonphysiologic motor stress,

a local myofascial release of irritants, or a combination of

these

2/3/2023

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-45-320.jpg)

![Tension–type headache [3]

Following activation of supraspinal pain perception

structures, a self-limiting headache results in most

individuals

CTT headache can evolve from ETT headache in

predisposed individuals due to a change in central

circuits and nociceptors

It is likely that other pathophysiologic mechanisms also

contribute to the development of tension-type headache

2/3/2023

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-46-320.jpg)

![Tension–type headache [4]

Clinical Presentation

The pain usually is mild to moderate in intensity

Often is described as a dull, nonpulsatile tightness or

pressure.

Bilateral pain is most common, but the location can vary

The pain is classically described as having a "hatband"

pattern.

Associated symptoms generally are absent, but mild

photophobia or phonophobia may be reported.

The disability associated with tension-type headache

typically is minor

2/3/2023

47](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-47-320.jpg)

![Tension–type headache [5]

Treatment

General Approach to Treatment

The vast majority of episodic tension-type headache

sufferers self-medicate with OTC medications

Simple analgesics and NSAIDs are the mainstay of acute

therapy.

Most agents used for tension-type headache have not been

studied in controlled clinical trials

2/3/2023

48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-48-320.jpg)

![Tension–type headache [6]

Nonpharmacologic Therapy

Psychophysiologic therapy and physical therapy have

been used in the management of tension-type

headache.

Behavioral therapies can consist of reassurance and

counseling, stress management, relaxation training,

and biofeedback.

These therapies (alone or in combination) can result in

a 35% to 50% reduction in headache activity.

2/3/2023

49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-49-320.jpg)

![Tension–type headache [7]

Pharmacologic Therapy

Simple analgesics (alone or in combination with caffeine) and

NSAIDs are effective for the acute treatment of most mild to

moderate tension-type headaches.

the following have demonstrated efficacy in placebo

controlled and comparative studies.

Acetaminophen, Aspirin,

Ibuprofen, naproxen,

ketoprofen, and ketorolac

2/3/2023

50](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-50-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [2]

The male-to-female ratio for cluster headache is

approximately 4:1

Age of onset typically in the third to fifth decade.

Up to 85% of patients with cluster headache are

tobacco smokers or have a history of smoking.

Tobacco cessation does not, however, seem to improve

the course of cluster headaches.

Recent genetic epidemiologic surveys support a

predisposition for cluster headache can exist in certain

families. 2/3/2023

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-52-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [3]

Cluster headache is one of a group of disorders

referred to as trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias.

This autonomic nervous system dysfunction is

characterized by SNS underactivity coupled with PNS

activation

The pain is believed to be the result of vasoactive

neuropeptide release and neurogenic inflammation.

The exact cause of trigeminal activation in this

intermittently manifest syndrome is unclear

2/3/2023

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-53-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [4]

Hypothalamic dysfunction, occasioned by diurnal or

seasonal changes in neurohumoral balance, may

responsible for headache periodicity

Serotonin affects neuronal activity and may play a role

in the pathophysiology of cluster headache.

The precipitation of cluster headache by high-altitude

exposure also implicates hypoxemia in the pathogenesis

Hypothalamus-regulated changes in cortisol, prolactin,

testosterone, growth hormone, leuteinizing hormone,

endorphin, and melatonin have been found during

periods of cluster headache attack.

2/3/2023

54](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-54-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [5]

Neuroimaging studies performed during acute cluster

headache attacks have demonstrated activation of the

ipsilateral hypothalamic gray area,

Implicating the thalamus as a cluster generator.

Significant cranial autonomic activation occurs

ipsilateral to the pain

2/3/2023

55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-55-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [6]

Patients experiencing “cluster headache” may display

the following headache symptoms and characteristics:

At least one or more of the following symptoms:

Lacrimation

Nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhea

Eyelid edema

Forehead or facial sweating/flushing

Sensation of fullness in the ear

Miosis and/or ptosis

Or a sense of restlessness or agitation

2/3/2023

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-56-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [7]

Duration of pain: 15–180 minutes (untreated)

Frequency of attacks: One every other day and/or

up to 8 per day for more than half the time the

disorder is active

Criteria for diagnosis: Five or more attacks

fulfilling the above criteria

2/3/2023

57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-57-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [8]

Treatment

As in migraine, therapy for cluster headaches involves

both abortive and prophylactic therapy.

Abortive therapy is directed at managing the acute

attack.

Prophylactic therapies are started early in the cluster

period in an attempt to induce remission.

Patients with chronic cluster headache can require

prophylactic medications indefinitely

2/3/2023

58](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-58-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [9]

Abortive Therapy

Oxygen

The standard acute treatment of cluster headache is

inhalation of 100% oxygen by non breather facial mask at

a rate of 7 to 10 L/min for 15 to 30 minutes.

Repeat administration can be necessary because of

recurrence, as oxygen appears to merely delay, rather than

abort, the attack in some patients.

No side effects have been reported with the use of oxygen,

but caution should be used for those who smoke or have

COPD

2/3/2023

59](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-59-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [10]

Ergotamine Derivatives

All forms of ergotamine have been used in cluster

headaches,

But no controlled clinical trials support their use.

In clinical use, intravenous dihydroergotamine results in the

quickest response,

Repeated administration for 3 to 7 days can break the cycle

of frequent attacks.

2/3/2023

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-60-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [11]

Ergotamine tartrate also has provided effective relief

of cluster headache attacks when administered

sublingually or rectally,

But the pharmacokinetics of these preparations

frequently limit their clinical utility.

Dosing guidelines are similar to those for migraine

headache therapy

2/3/2023

61](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-61-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [12]

Triptans

The quick onset of subcutaneous and intranasal triptans make

them safe and effective abortive agents for cluster

headaches

Subcutaneous Sumatriptan (6 mg) is the most effective agent.

Nasal sprays are less effective but may be better tolerated

in Some patients.

Adverse events reported in cluster headache patients are

similar to those seen in migraineurs.

Orally administered triptans have limited use in cluster

attacks because of their relatively slow onset of action;

2/3/2023

62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-62-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [13]

Prophylactic Therapy

Verapamil, the preferred calcium channel blocker for the

prevention of cluster headaches,

It is effective in approximately 70% of patients.

The beneficial effects of verapamil often appear after 1

week of therapy.

A typical suggested dosage range is from 360 to 720

mg/day,

Some patients requiring up to 1,200 mg/day.

2/3/2023

63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-63-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [13]

Lithium

Lithium carbonate is effective for episodic and chronic

cluster headache attacks

Can also be used in combination with verapamil.

A positive response is seen in

Up to 78% of patients with chronic cluster headache,

And in up to 63% of patients with episodic cluster

headache.

The usual dose is 600 to 1,200 mg/day, with a

suggested starting dose of 300 mg twice daily..

2/3/2023

64](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-64-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [14]

Initial side effects are mild and include :

Tremor, lethargy,

Nausea, Diarrhea, and

Abdominal discomfort.

Thyroid and renal function must be monitored during

lithium therapy

2/3/2023

65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-65-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [15]

Ergotamine

Is efficacious for prophylactic as well as abortive therapy of

cluster headaches.

A 2-mg bedtime dose is often for the prevention of nocturnal

headache attacks.

Daily use of 1 to 2 mg ergotamine alone or in combination

with verapamil or lithium

Can provide effective headache prophylaxis in patients

refractory to other agents

Risk of ergotism or rebound headache little with this regimen

2/3/2023

66](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-66-320.jpg)

![Cluster headache [16]

Corticosteroids are useful for inducing remission.

Therapy is initiated with 40 to 60 mg/day prednisone

and tapered over approximately 3 weeks.

Relief appears within 1 to 2 days of initiating therapy.

To avoid steroid-induced complications, long-term use

is not recommended.

Headaches can recur when therapy is tapered or

discontinued

2/3/2023

67](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-67-320.jpg)

![Therapeutic outcome evaluation [2]

Patients using acute therapies should be monitored to

identify potential medication-overuse headache.

Patient counseling is necessary to allow for proper

medication use

Strict adherence to dosing guidelines should be stressed

to minimize potential toxicity.

Patterns of abortive medication use can be documented

to establish the need for prophylactic therapy.

Prophylactic therapies also should be monitored closely

(every 3-6 months until stable) 2/3/2023

69](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/headachedisordersmubarik-241005224720-e4dfaf1b/85/Headache-Disorders-used-for-all-pharmacy-student-69-320.jpg)