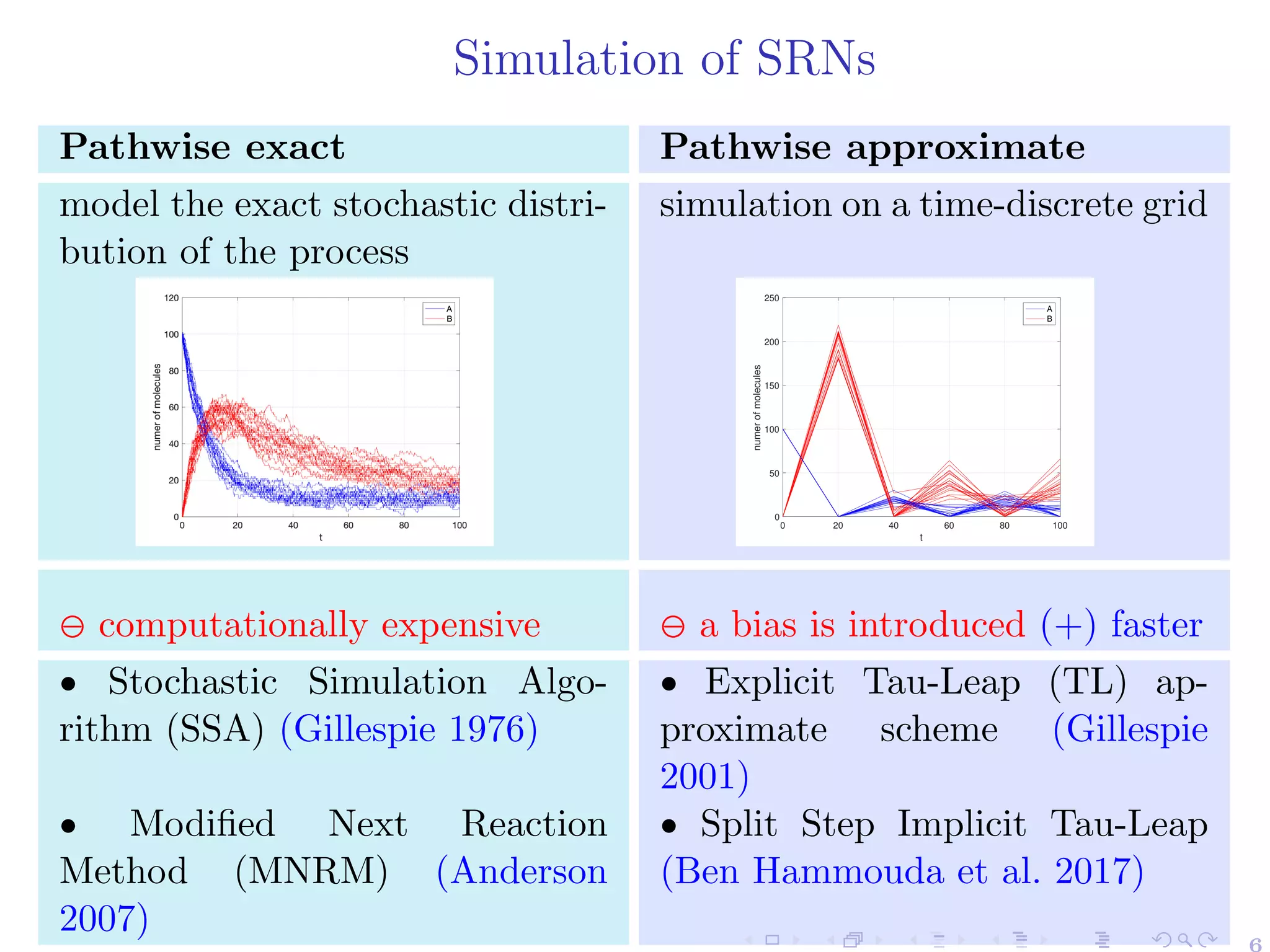

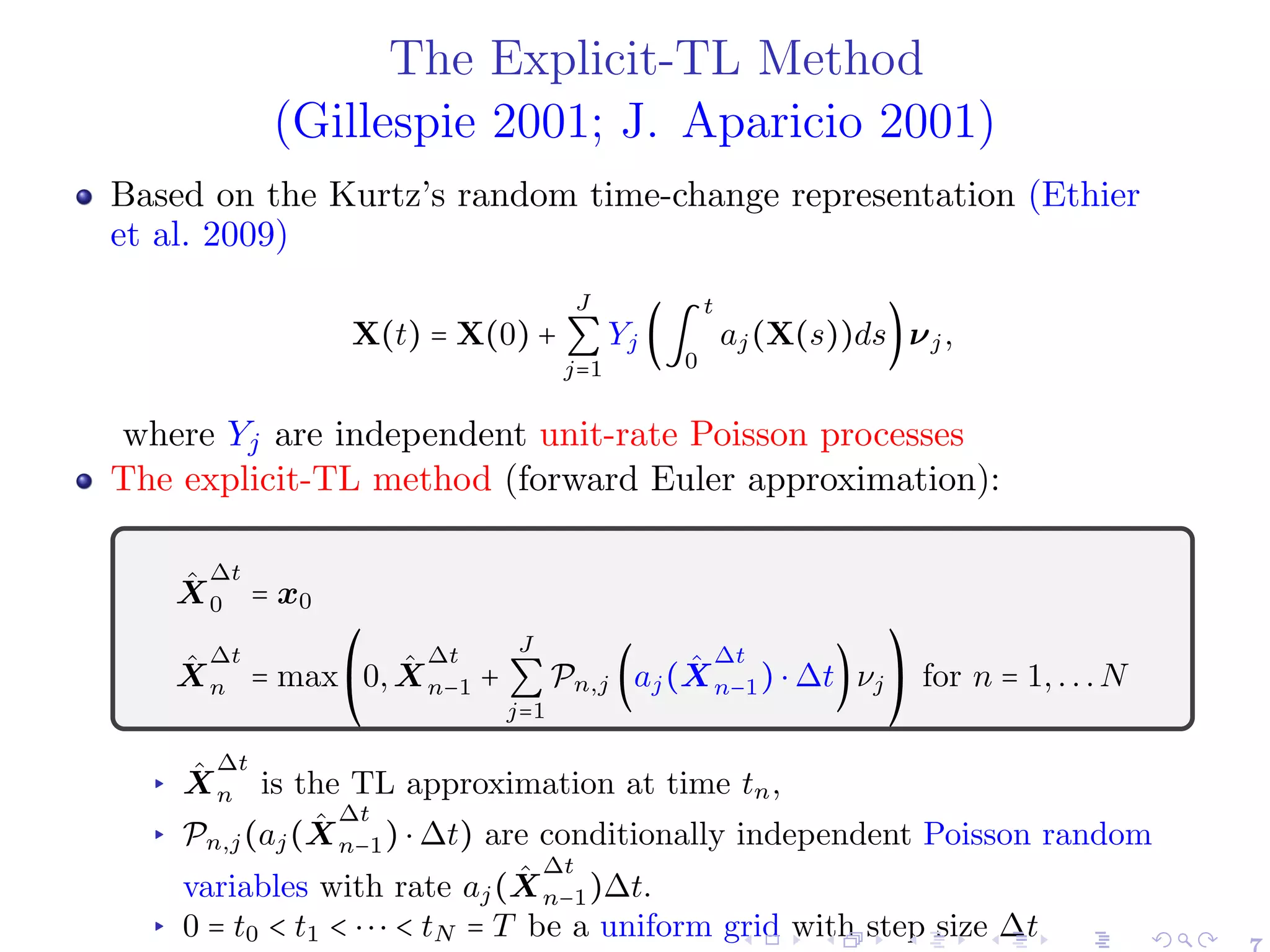

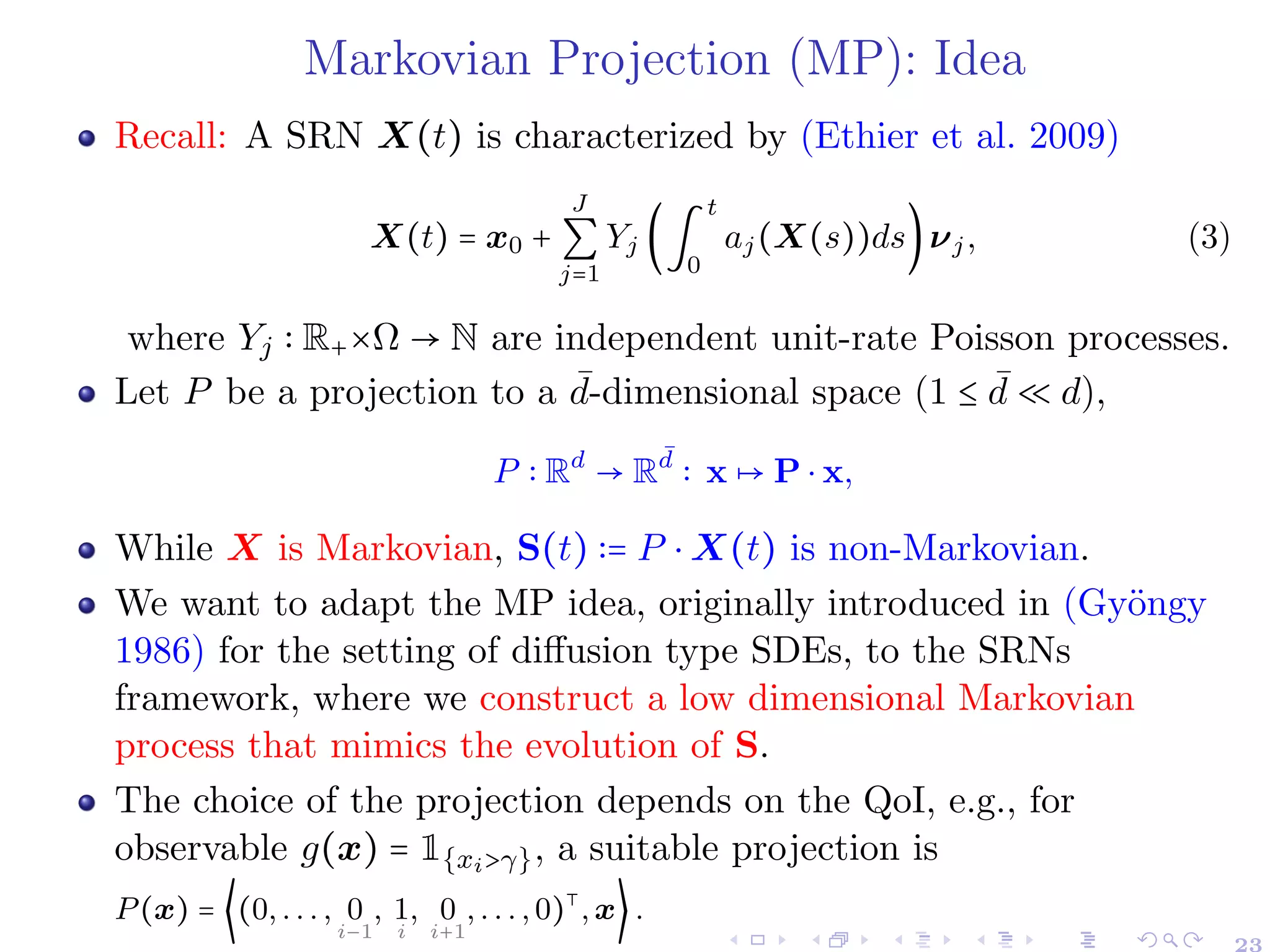

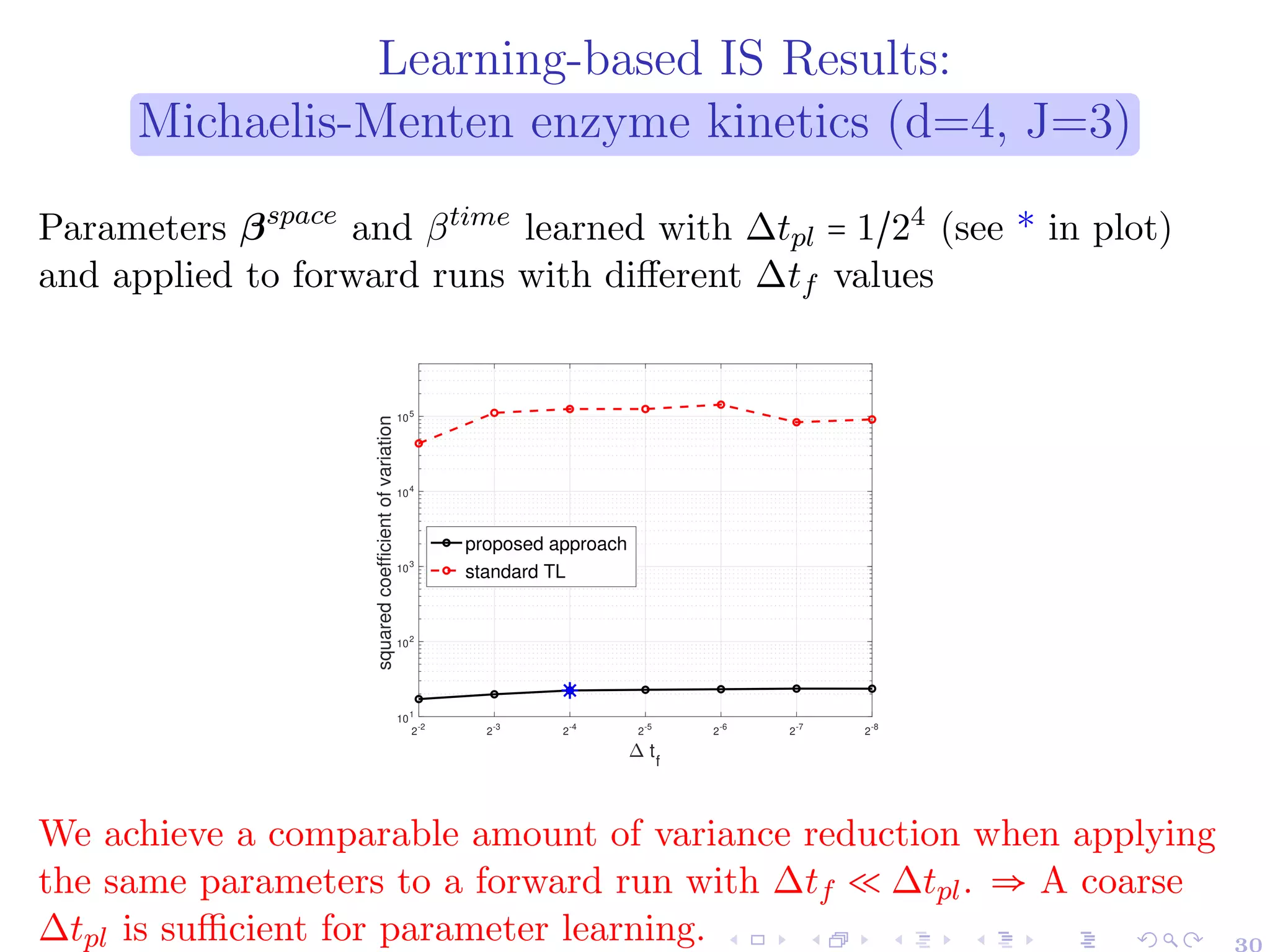

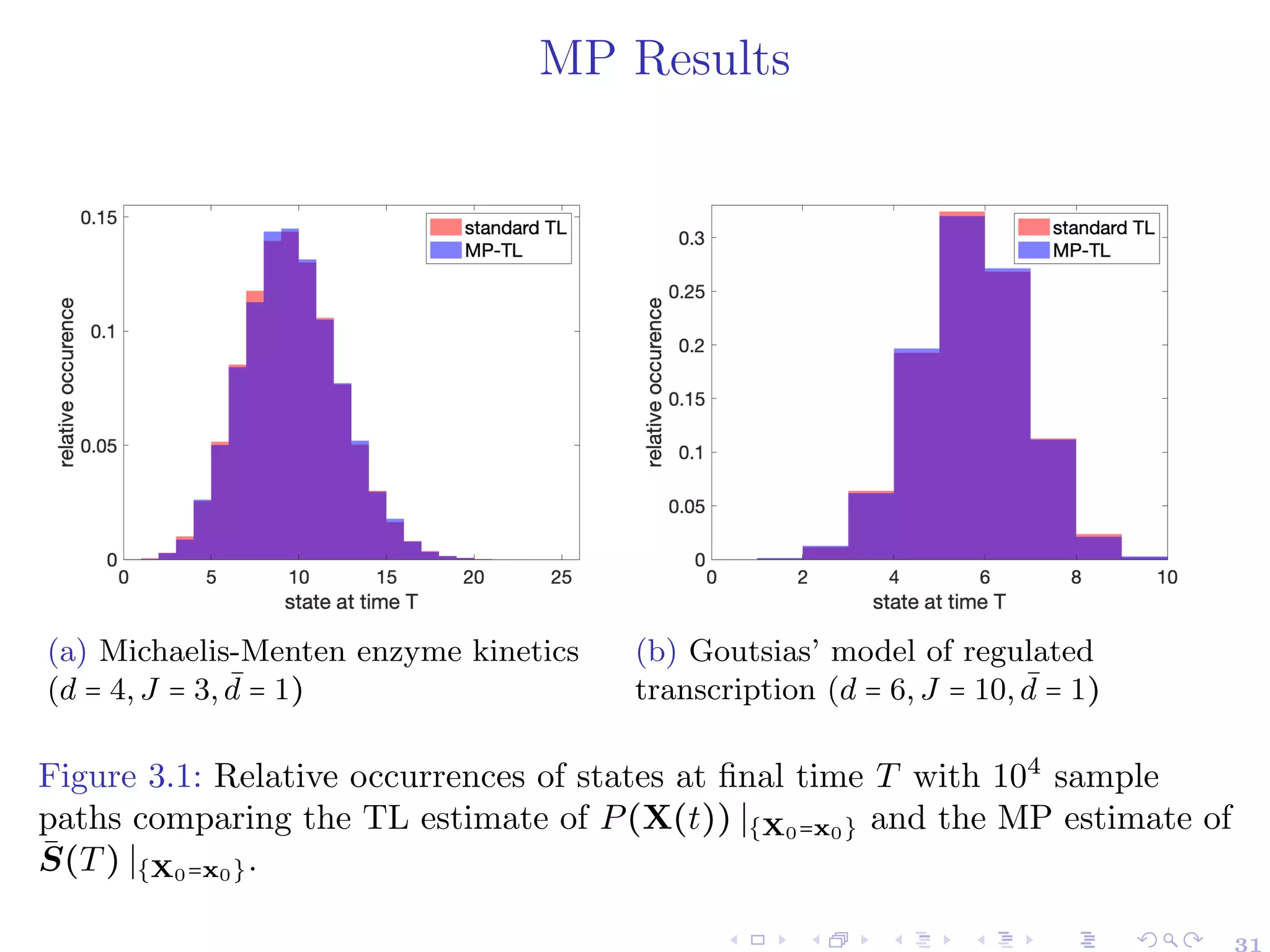

The document discusses the design of efficient Monte Carlo estimators for rare event probabilities in stochastic reaction networks using optimal importance sampling via stochastic optimal control. Two approaches are explored: a learning-based method for the value function and controls through stochastic optimization, and a Markovian projection-based method for solving reduced-dimensional Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equations. The goal is to address challenges like the curse of dimensionality while providing numerical experiments and results to support these methodologies.

![Stochastic Reaction Network (SRNs)

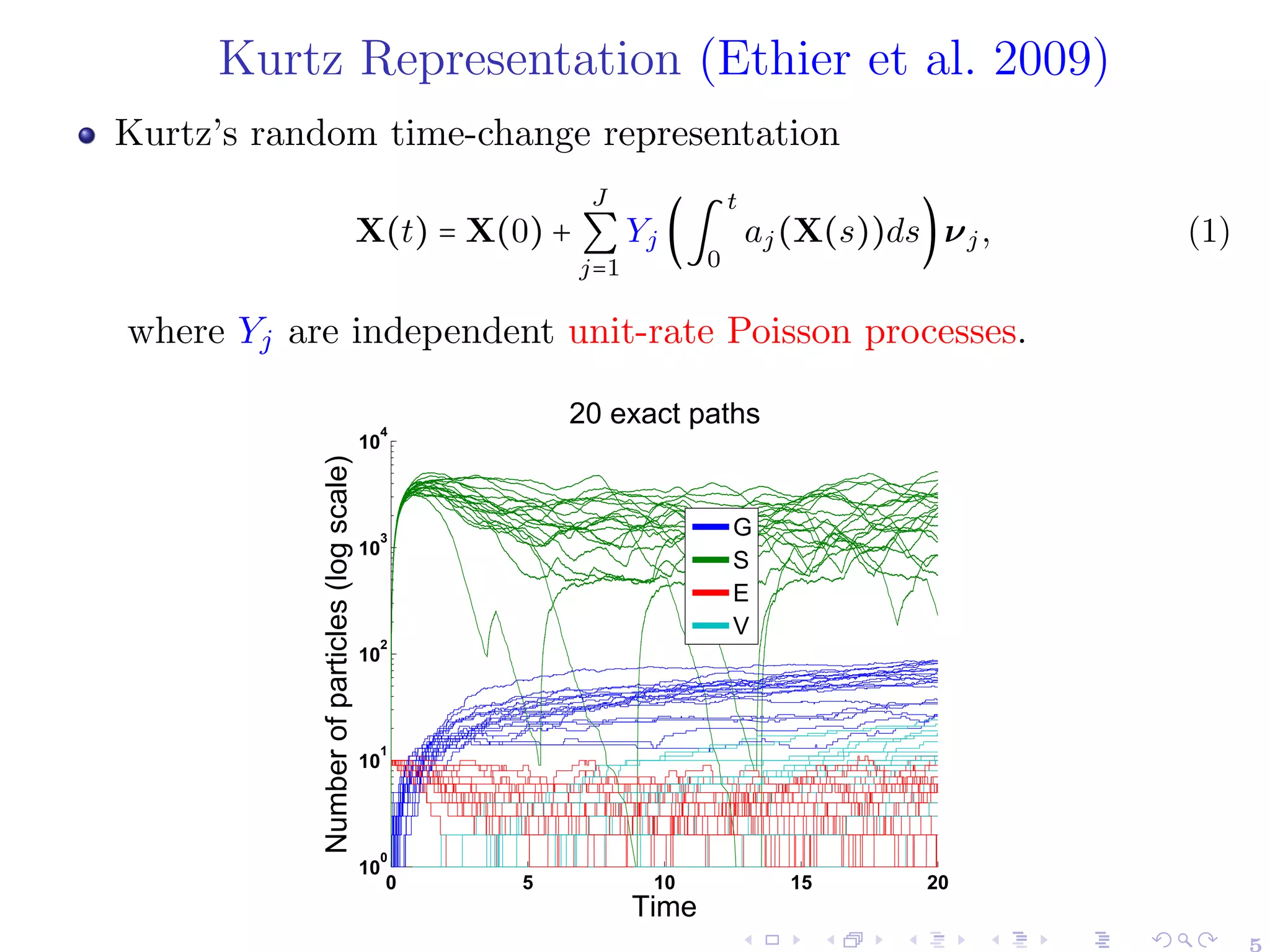

A stochastic reaction network (SRN) is a continuous-time Markov

chain, X(t), defined on a probability space (Ω,F,P)1

X(t) = (X(1)

(t),...,X(d)

(t)) ∶ [0,T] × Ω → Nd

described by J reactions channels, Rj ∶= (νj,aj), where

▸ νj ∈ Zd

: stoichiometric (state change) vector.

▸ aj ∶ Rd

+ → R+: propensity (jump intensity) function.

aj satisfies

P(X(t + ∆t) = x + νj ∣ X(t) = x) = aj(x)∆t + o(∆t), j = 1,...,J.

1

X(i)

(t) may describe the abundance (counting number) of the i-th species

(agent) present in the system at time t. 4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-6-2048.jpg)

![Importance Sampling (IS) for MC

Let Y be a real r.v.

IS is a change of measure, and it reduces the MC computational

cost by sampling on regions with the most effect on the QoI.

Instead of approximating EP

[Y ] with MC, IS uses MC for

EQ

[Y dP

dQ ].

The minimum variance is then

V arQ∗

[Y

dP

dQ∗

] = (EP

[∣Y ∣])

2

(1 − (EQ∗

[1{Y >0}] − EQ∗

[1{Y <0}])

2

)

IS-MC will be more efficient than plain MC when

V arP

[Y ]/(EP

[∣Y ∣])

2

>> 1 or Y has near constant sign, i.e.

V arQ∗

[Y

dP

dQ∗

](1 + θ) < V arP

[Y ]

Here (1 + θ) ≥ 1 is the relative cost of sampling Y dP

dQ∗ under Q∗

wrt sampling Y under P.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-10-2048.jpg)

![Aim and Setting

Design a computationally efficient MC estimator for

E[g(X(T))] using IS:

▸ We are interested in g(X(T)) = 1{X(T )∈B} for a set B ⊆ Nd

for

rare event applications: E[g(X(T))] = P(X(T) ∈ B) ≪ 1

▸ {X(t) ∶ t ∈ [0,T]} is a SRNs.

Challenge

IS often requires insights into the given problem.

Solution

Propose an automated path dependent measure change based on a

novel connection between finding optimal IS parameters and a SOC

formulation, corresponding to solving a variance minimization

problem.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-11-2048.jpg)

![SOC Formulation for the IS scheme

Aim: Find IS parameters which result in the lowest possible variance

Value Function

Let u∆t(⋅,⋅) be the value function which gives the optimal second

moment. For time step 0 ≤ n ≤ N and state x ∈ Nd

:

u∆t(n,x) ∶= inf

{δ∆t

i }i=n,...,N−1∈AN−n

E[g2

(X

∆t

N )

N−1

∏

i=n

Li(P i,δ∆t

i (X

∆t

i ))

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

likelihood factor

2

∣X

∆t

n = x]

Notation:

A = ⨉x∈Nd ⨉J

j=1 Ax,j is the admissible set for the IS parameters.

Li(P i,δ∆t

i (X

∆t

i )) =

exp(−(∑J

j=1 aj(X

∆t

i ) − δ∆t

i,j (X

∆t

i ))∆t) ⋅ ∏J

j=1 (

aj(X

∆t

i )

δ∆t

i,j (X

∆t

i )

)

Pi,j

(P i)j ∶= Pi,j and (δi)j ∶= δi,j

" Compared with the classical SOC formulation, our expected total

cost uses a multiplicative cost structure rather than the additive one.

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-14-2048.jpg)

![Approximate DP and near-Optimal IS Parameters

Idea: Approximate the value function u∆t(n,x) by Taylor expansion, and

truncation of the Taylor series and the infinite sum up to O(∆t2

)

u∆t(N,x) = g2

(x) , and for x ∈ N and n = N − 1,...,0 ∶

u∆t(n,x) = u∆t(n + 1,x)

⎛

⎝

1 − 2∆t

J

∑

j=1

aj(x)

⎞

⎠

+ ∆t ⋅

J

∑

j=1

Q∆t

(n,j,x).

For u∆t(n + 1,max(0,x + νj)) ≠ 0 (1 ≤ j ≤ J) and u∆t(n + 1,x) ≠ 0 :

δ

∆t

n,j(x) =

aj(x)

√

u∆t(n + 1,max(0,x + νj))

√

u∆t(n + 1,x)

Q∆t

(n,j,x) ∶= inf

δj ∈Ax,j

[

a2

j (x)

δj

u∆t(n + 1,max(0,x + νj)) + δju∆t(n + 1,x)]

= 2aj(x)

√

u∆t(n + 1,max(0,x + νj)) ⋅ u∆t(n + 1,x)

" Our numerical approximation reduces the complexity of the original

problem at each step from a simultaneous optimization over J variables to

decoupled/independent one-dimensional ones that can be solved in parallel.

" The conditions for attainability ensured either by some regularization

(Wiechert 2021) or modeling u∆t(⋅,⋅) using a strictly positive ansatz

function as in (Ben Hammouda et al. 2023b). 13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-16-2048.jpg)

![Numerical Dynamic Programming:

Curse of Dimensionality

The computational cost to numerically solve the previous dynamic

programming equation for step size ∆t and truncated state space

⨉d

i=1[0,Si] ⊂ Nd

can be expressed as

W(S,∆t) ≈

T

∆t

⋅ J ⋅ (S

∗

)d

, S̄∗

= max

i=1,...,d

S̄i

⊖ Computational cost scales exponentially with dimension d.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-17-2048.jpg)

![Learning-based Approach: Steps

1 Approximate the value function, u∆t(n,x), with an ansatz function, û(t,x;β):

u∆t(n,x) = inf

{δ∆t

i }i=n,...,N−1∈AN−n

E[g2

(X

∆t

N )

N−1

∏

i=n

Li(P̄ i,δ∆t

i (X

∆t

i ))

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

likelihood factor

2

∣X

∆t

n = x].

Illustration: For the observable g(X(T)) = 1{Xi(T)>γ} , we use the ansatz

û(t,x;β) =

1

1 + e−(1−t)⋅(<βspace

,x>+βtime)+b0−<β0,x>

, t ∈ [0,1], x ∈ Nd

learned parameters β = (βspace

,βtime

) ∈ Rd+1

, and

b0 and β0 are chosen to fit the final condition at time T (not learned)

Example sigmoid for d = 1:

● final fit for g(x) = 1{xi>10}

→ b0 = 14,β0 = 1.33

● βspace

= −0.5, βtime

= 1

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-21-2048.jpg)

![Learning-Based Approach: Steps

2 Use stochastic optimization (e.g. ADAM (Kingma et al. 2014))

to learn the parameters β = (βspace

,βtime

) ∈ Rd+1

which minimize

the second moment under IS:

inf

β∈Rd+1

E[g2

(X

∆t,β

N )

N−1

∏

k=0

L2

k (P̄ k,δ̂

∆t

(k,X

∆t,β

k ;β))]

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

=∶C0,X (δ̂

∆t

0 ,...,δ̂

∆t

N−1;β)

,

▸ (δ̂

∆t

(n,x;β))

j

= δ̂∆t

j (n,x;β) =

aj (x)

√

û∆t(

(n+1)∆t

T ,max(0,x+νj );β)

√

û∆t(

(n+1)∆t

T ,x;β)

▸ {X

∆t,β

n }n=1,...,N is an IS path generated with {δ̂

∆t

(n,x;β)}n=1,...,N

(+) We derive explicit pathwise derivatives, which are unbiased,

resulting in only the MC error for evaluating the expectation (i.e.,

without additional finite difference error).

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-22-2048.jpg)

![Learning-Based Approach: Steps

3 In the forward step, estimate E[g(X(T))] using the MC estimator

based on the proposed IS change of measure over M paths

µIS

M,∆t =

1

M

M

∑

i=1

Lβ∗

i ⋅ g(X

∆t,β∗

[i],N ),

where X

∆t,β∗

[i],N is the i-th IS sample path and Lβ∗

i is the

corresponding likelihood factor, both simulated with the IS

parameters obtained via the stochastic optimization step

δ̂j(n,x;β∗

) =

aj(x)

√

û((n+1)∆t

T

,max(0,x + νj);β∗

)

√

û((n+1)∆t

T

,x;β∗

)

, 0 ≤ n ≤ N − 1, x ∈ Nd

,

,1 ≤ j ≤ J

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-24-2048.jpg)

![HJB equations for IS Parameters

of the full-dimensional SRNs

Corollary (Ben Hammouda et al. 2023a)

For x ∈ Nd

, an approximate continuous-time value function ũ(t,x) fulfills the

Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman (HJB) equations for t ∈ [0,T]

ũ(T,x) = g2

(x)

−

dũ

dt

(t,x) = inf

δ(t,x)∈Ax

⎛

⎝

−2

J

∑

j=1

aj(x) +

J

∑

j=1

δj(t,x)

⎞

⎠

ũ(t,x) +

J

∑

j=1

aj(x)2

δj(t,x)

ũ(t,max(0,x + νj)),

where δj(t,x) ∶= (δ(t,x))j.

For If ũ(t,x) > 0 for all x ∈ Nd

and t ∈ [0,T] :

▸ δ̃j(t,x) = aj(x)

√

ũ(t,max(0,x+νj ))

ũ(t,x)

▸ dũ

dt

(t,x) = −2∑

J

j=1 aj(x)(

√

ũ(t,x)ũ(t,max(0,x + νj)) − ũ(t,x))

For rare event probabilities, we approximate the observable g(x) = 1xi>γ

by a sigmoid: g̃(x) = 1

1+exp(b−βxi), with appropriately chosen parameters

b ∈ R and β ∈ R.

⊖ Computational cost to solve HJB Equ. scales exponentially with dimension

d.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-26-2048.jpg)

![Markovian Projection for SRNs

For t ∈ [0,T], let us consider the projected process as S(t) ∶= P ⋅ X(t),

where X(t) follows (3).

Theorem ((Ben Hammouda et al. 2023a))

For t ∈ [0,T], let S̄(t) be a ¯

d-dimensional stochastic process, whose

dynamics are given by

S̄(t) = P(x0) +

J

∑

j=1

Ȳj (∫

t

0

āj(τ,S̄(τ))dτ)P(νj)

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

=∶ν̄j

,

where Ȳj are independent unit-rate Poisson processes and āj are

characterized by

āj(t,s) ∶= E[aj(X(t))∣P (X(t)) = s,X(0) = x0], for 1 ≤ j ≤ J,s ∈ N

¯

d

.

Then, S(t) ∣{X(0)=x0} and S̄(t) ∣{X(0)=x0} have the same conditional

distribution for all t ∈ [0,T].

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-29-2048.jpg)

![Propensities of the Projected Process

Under MP, the propensity becomes time-dependent

āj(t,s) ∶= E[aj(X(t)) ∣ P (X(t)) = s;X(0) = x0], for 1 ≤ j ≤ J,s ∈ N

¯

d

The index set of the projected propensities is (#JMP ≤ J)

JMP ∶= {1 ≤ j ≤ J ∶ P(νj) ≠ 0 and aj(x) ≠ f(P(x)) ∀f ∶ R

¯

d

→ R}.

To approximate āj for j ∈ JMP , we use discrete L2

regression:

āj(⋅,⋅) = argminh∈V ∫

T

0

E[(aj(X(t)) − h(t,P(X(t))))

2

]dt

≈ argminh∈V

1

M

M

∑

m=1

1

N

N−1

∑

n=0

(aj(X̂∆t

[m],n) − h(tn,P(X̂∆t

[m],n)))

2

▸ V ∶= {f ∶ [0,T] × R

¯

d

→ R ∶ ∫

T

0 E[f(t,P(X(t))2

)]dt < ∞}

▸ {X̂∆t

[m]}

M

m=1

are M independent TL paths on a uniform time grid

0 = t0 < t1 < ⋅⋅⋅ < tN = T with step size ∆t.

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-30-2048.jpg)

![IS for SRNs via MP: Steps

1 Perform the MP as described in the previous slides

2 For t ∈ [0,T], solve the reduced-dimensional HJB equations

(system of ODEs) corresponding to the MP process

ũ¯

d(T,s) = g̃2

(s), s ∈ N

¯

d

dũ¯

d

dt

(t,s) = −2

J

∑

j=1

āj(t,s)(

√

ũ¯

d(t,s)ũ¯

d(t,max(0,s + ν̄j)) − ũ¯

d(t,s)), s ∈ N

¯

d

.

3 Obtain the continuous-time IS controls for the d-dimensional SRN

δ̄j(t,x) = aj(x)

¿

Á

Á

Àũ¯

d (t,max(0,P(x + νj)))

ũ¯

d (t,P(x))

, for x ∈ Nd

,t ∈ [0,T].

4 Construct the MP-IS-MC estimator for a given uniform time grid

0 = t0 ≤ t1 ≤ ⋅⋅⋅ ≤ tN = T with stepsize ∆t, with TL paths using the

IS control parameters δ̄j(tn,x), j = 1,...,J,x ∈ Nd

,n = 0,...,N − 1.

26](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-31-2048.jpg)

![Related References

Thank you for your attention!

[1] C. Ben Hammouda, N. Ben Rached, R. Tempone, S. Wiechert. Automated

Importance Sampling via Optimal Control for Stochastic Reaction

Networks: A Markovian Projection-based Approach. To appear soon (2023).

[2] C. Ben Hammouda, N. Ben Rached, R. Tempone, S. Wiechert.

Learning-based importance sampling via stochastic optimal control for

stochastic reaction networks. Statistics and Computing, 33, no. 3 (2023).

[3] C. Ben Hammouda, N. Ben Rached, R. Tempone. Importance sampling for

a robust and efficient multilevel Monte Carlo estimator for stochastic

reaction networks. Statistics and Computing, 30, no. 6 (2020).

[4] C. Ben Hammouda, A. Moraes, R. Tempone. Multilevel hybrid split-step

implicit tau-leap. Numerical Algorithms, 74, no. 2 (2017).

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-45-2048.jpg)

![References I

[1] David F Anderson. “A modified next reaction method for simulating chemical

systems with time dependent propensities and delays”. In: The Journal of chemical

physics 127.21 (2007), p. 214107.

[2] David F Anderson and Thomas G Kurtz. Stochastic analysis of biochemical systems.

Springer, 2015.

[3] C. Ben Hammouda et al. “Automated Importance Sampling via Optimal Control for

Stochastic Reaction Networks: A Markovian Projection-based Approach”. In: To

appear soon (2023).

[4] C. Ben Hammouda et al. “Learning-based importance sampling via stochastic

optimal control for stochastic reaction networks”. In: Statistics and Computing 33.3

(2023), p. 58.

[5] Chiheb Ben Hammouda, Alvaro Moraes, and Raúl Tempone. “Multilevel hybrid

split-step implicit tau-leap”. In: Numerical Algorithms 74.2 (2017), pp. 527–560.

[6] Chiheb Ben Hammouda, Nadhir Ben Rached, and Raúl Tempone. “Importance

sampling for a robust and efficient multilevel Monte Carlo estimator for stochastic

reaction networks”. In: Statistics and Computing 30.6 (2020), pp. 1665–1689.

[7] Corentin Briat, Ankit Gupta, and Mustafa Khammash. “A Control Theory for

Stochastic Biomolecular Regulation”. In: SIAM Conference on Control Theory and

its Applications. SIAM. 2015.

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-46-2048.jpg)

![References II

[8] Nai-Yuan Chiang, Yiqing Lin, and Quan Long. “Efficient propagation of

uncertainties in manufacturing supply chains: Time buckets, L-leap, and multilevel

Monte Carlo methods”. In: Operations Research Perspectives 7 (2020), p. 100144.

[9] Stewart N Ethier and Thomas G Kurtz. Markov processes: characterization and

convergence. Vol. 282. John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

[10] D. T. Gillespie. “Approximate accelerated stochastic simulation of chemically

reacting systems”. In: Journal of Chemical Physics 115 (July 2001), pp. 1716–1733.

doi: 10.1063/1.1378322.

[11] Daniel Gillespie. “Approximate accelerated stochastic simulation of chemically

reacting systems”. In: The Journal of chemical physics 115.4 (2001), pp. 1716–1733.

[12] Daniel T Gillespie. “A general method for numerically simulating the stochastic time

evolution of coupled chemical reactions”. In: Journal of computational physics 22.4

(1976), pp. 403–434.

[13] John Goutsias. “Quasiequilibrium approximation of fast reaction kinetics in

stochastic biochemical systems”. In: The Journal of chemical physics 122.18 (2005),

p. 184102.

[14] John Goutsias and Garrett Jenkinson. “Markovian dynamics on complex reaction

networks”. In: Physics reports 529.2 (2013), pp. 199–264.

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-47-2048.jpg)

![References III

[15] István Gyöngy. “Mimicking the one-dimensional marginal distributions of processes

having an Itô differential”. In: Probability theory and related fields 71.4 (1986),

pp. 501–516.

[16] SebastianC. Hensel, JamesB. Rawlings, and John Yin. “Stochastic Kinetic Modeling

of Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Intracellular Growth”. English. In: Bulletin of

Mathematical Biology 71.7 (2009), pp. 1671–1692. issn: 0092-8240.

[17] H. Solari J. Aparicio. “Population dynamics: Poisson approximation and its relation

to the langevin process”. In: Physical Review Letters (2001), p. 4183.

[18] Hye-Won Kang and Thomas G Kurtz. “Separation of time-scales and model

reduction for stochastic reaction networks”. In: (2013).

[19] Diederik P Kingma and Jimmy Ba. “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization”.

In: arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

[20] Hiroyuki Kuwahara and Ivan Mura. “An efficient and exact stochastic simulation

method to analyze rare events in biochemical systems”. In: The Journal of chemical

physics 129.16 (2008), 10B619.

[21] Christopher V Rao and Adam P Arkin. “Stochastic chemical kinetics and the

quasi-steady-state assumption: Application to the Gillespie algorithm”. In: The

Journal of chemical physics 118.11 (2003), pp. 4999–5010.

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-48-2048.jpg)

![References IV

[22] Elijah Roberts et al. “Noise Contributions in an Inducible Genetic Switch: A

Whole-Cell Simulation Study”. In: PLoS computational biology 7 (Mar. 2011),

e1002010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002010.

[23] Sophia Wiechert. “Optimal Control of Importance Sampling Parameters in Monte

Carlo Estimators for Stochastic Reaction Networks”. MA thesis. 2021.

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kausttalkshort-230531154446-ae89ff73/75/KAUST_talk_short-pdf-49-2048.jpg)