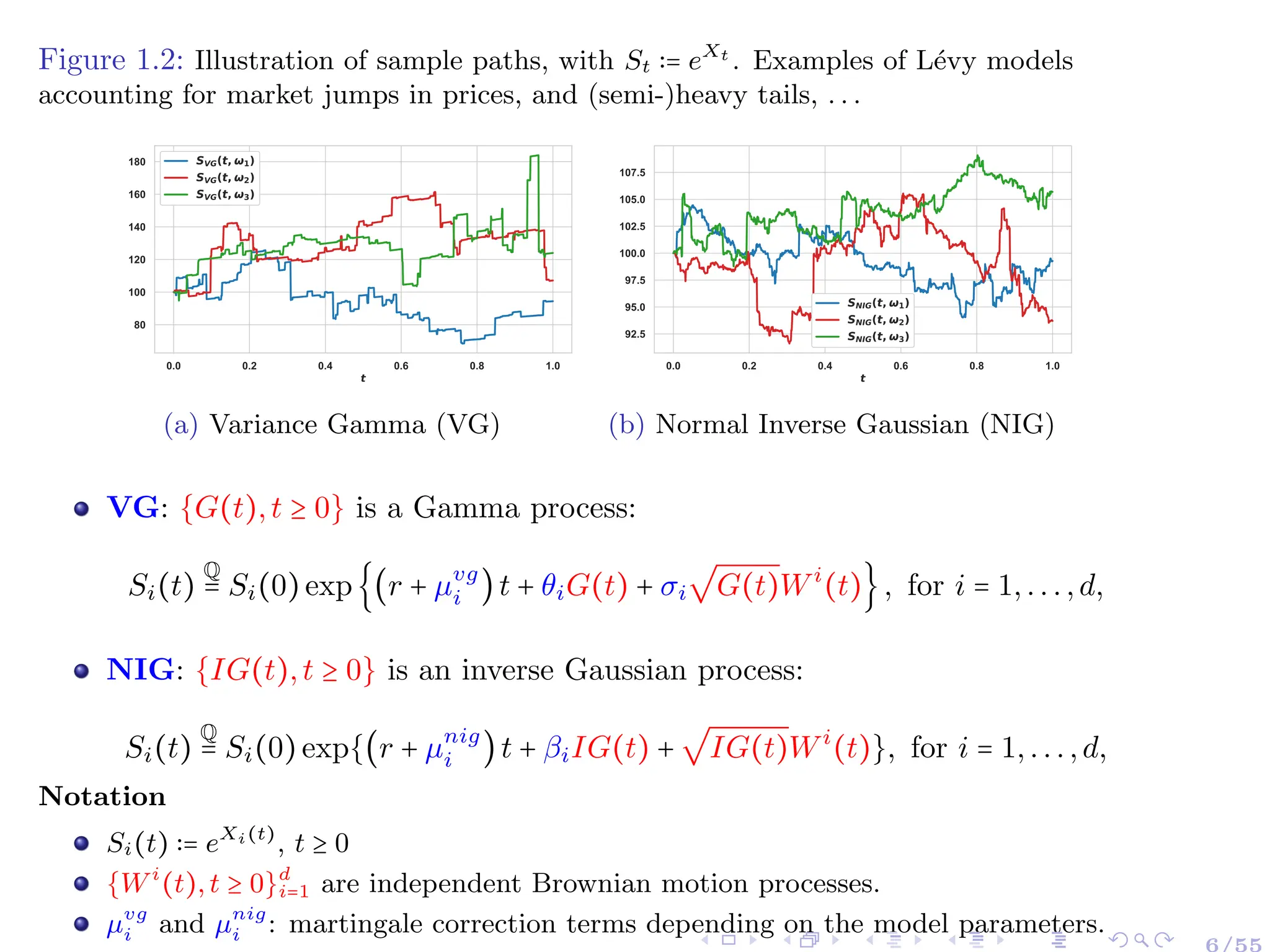

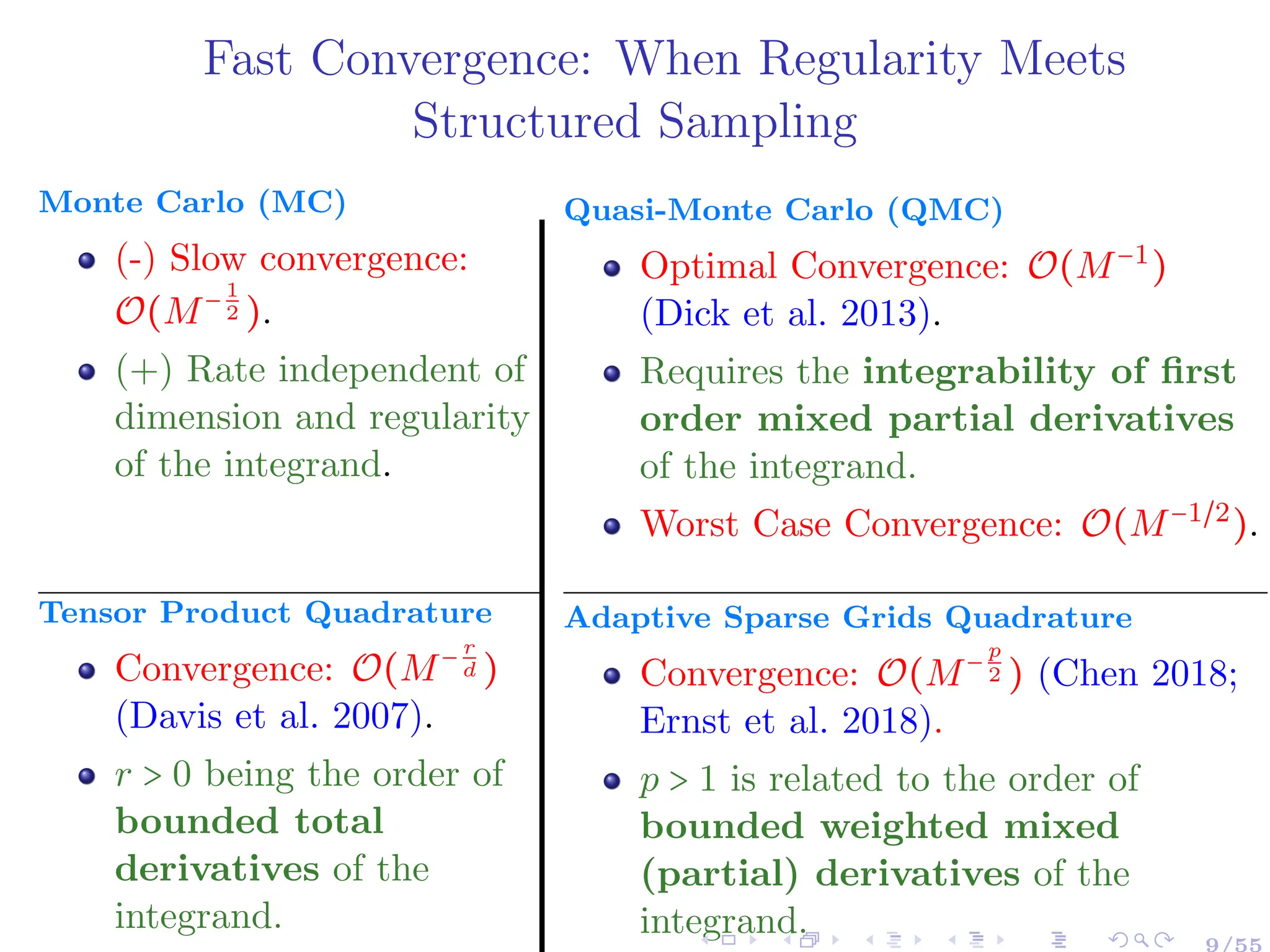

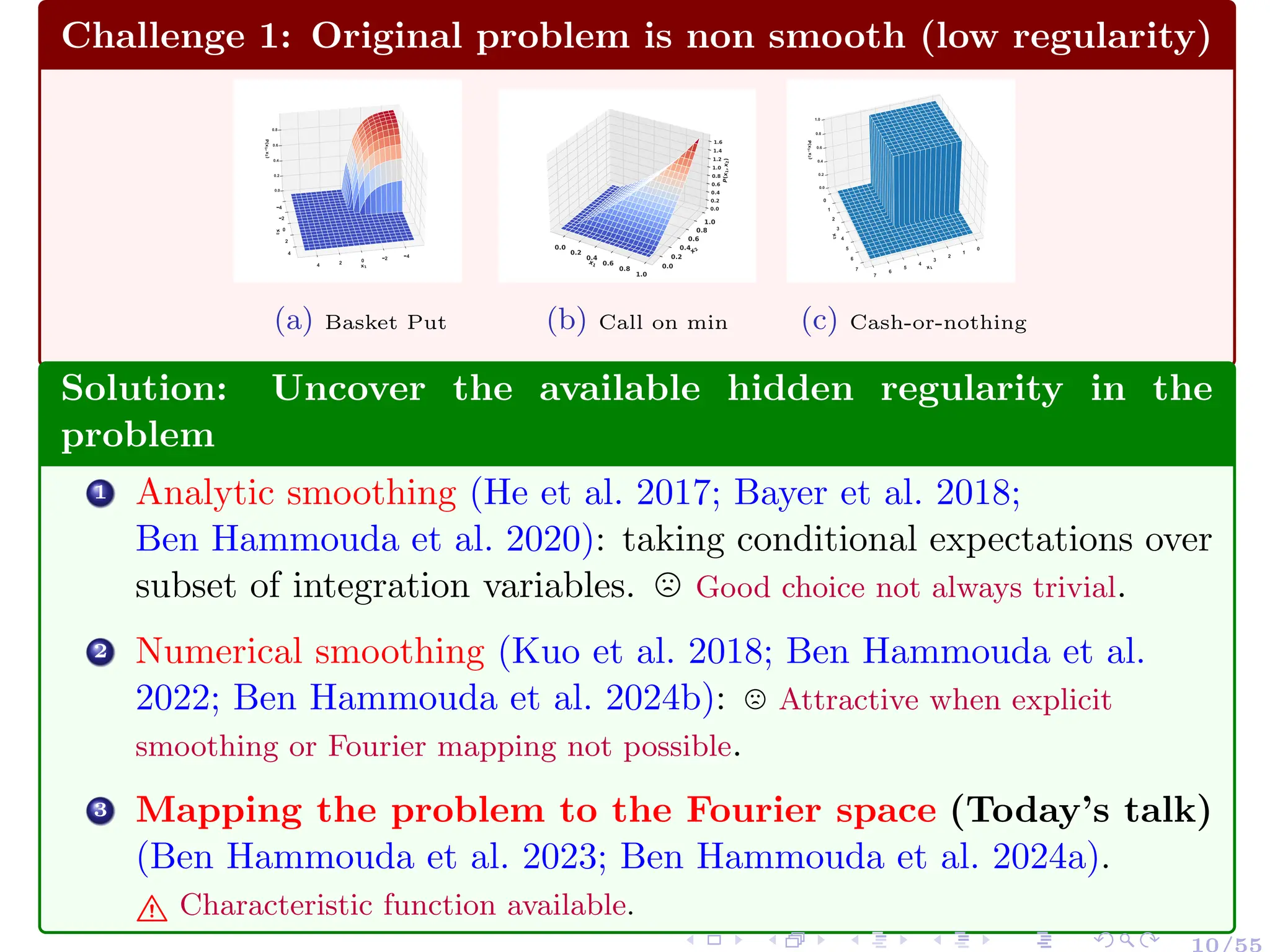

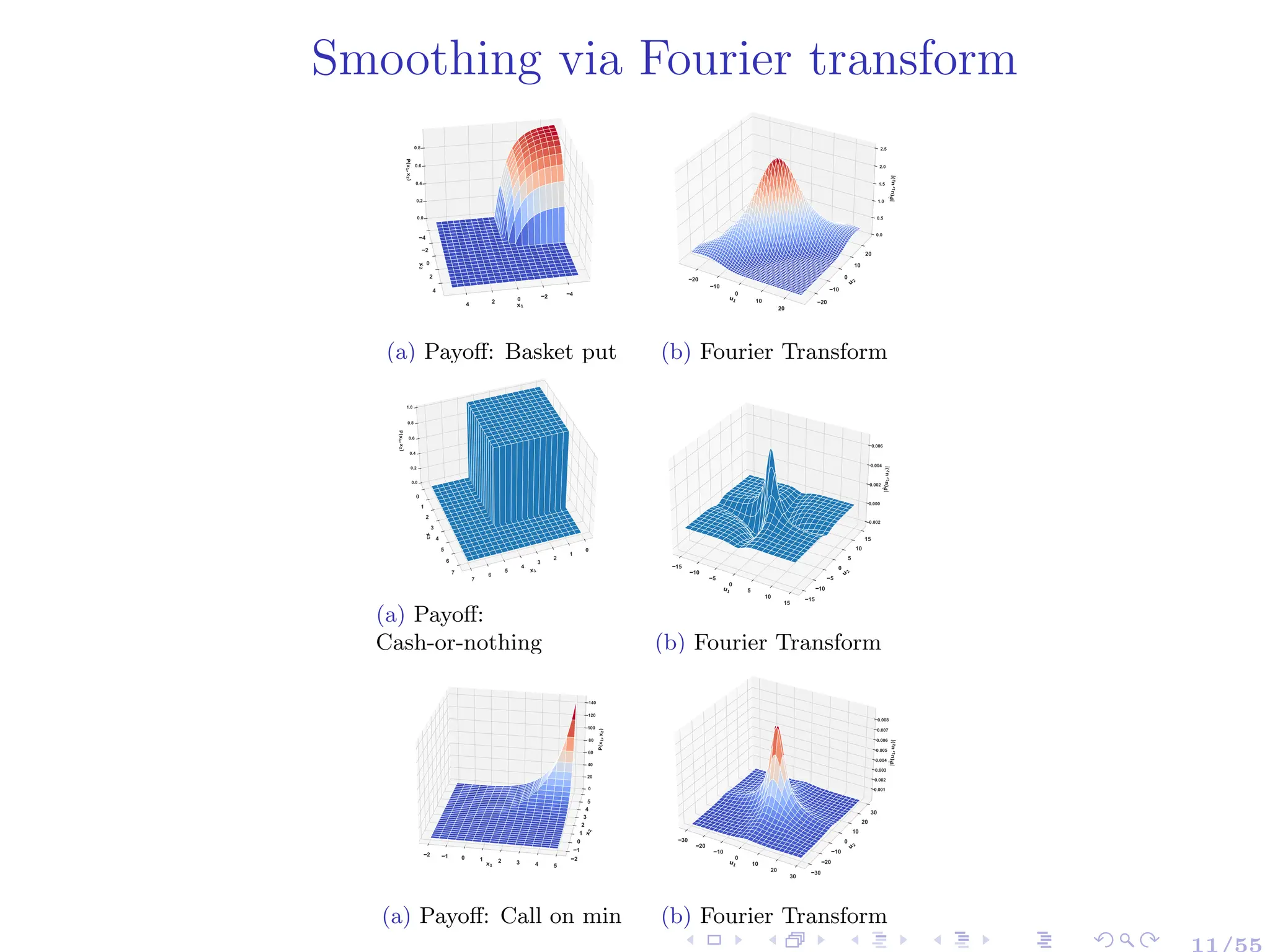

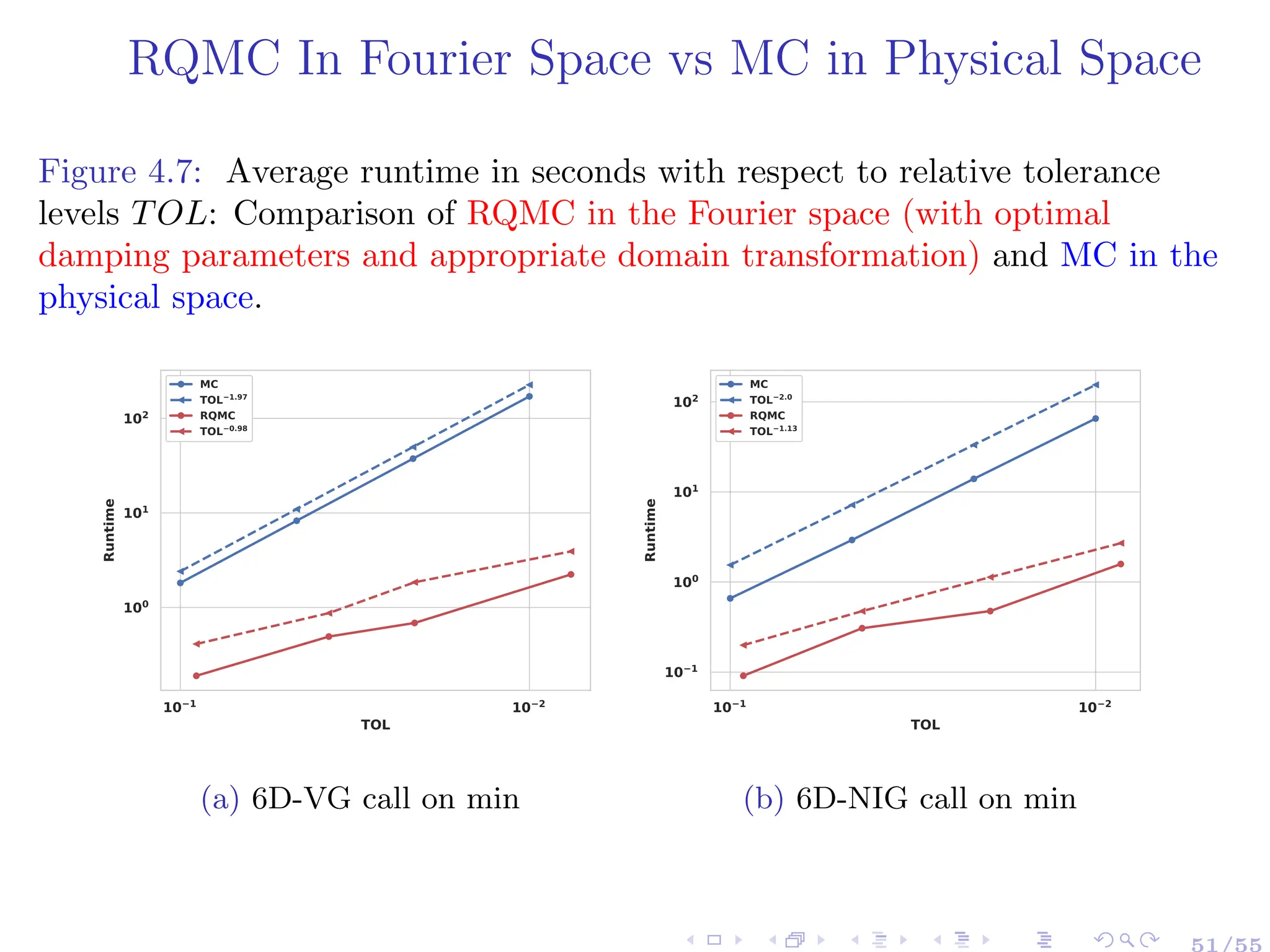

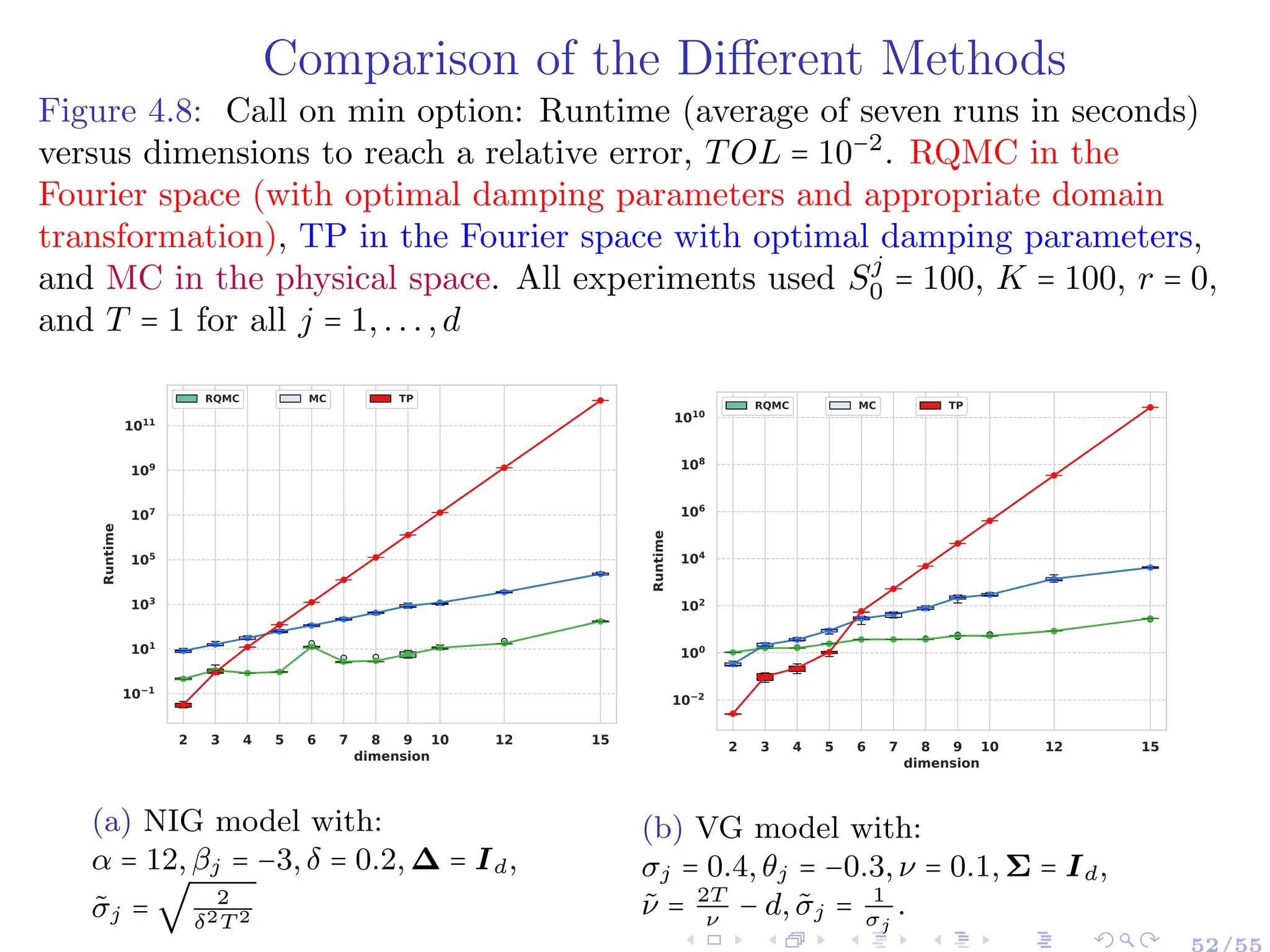

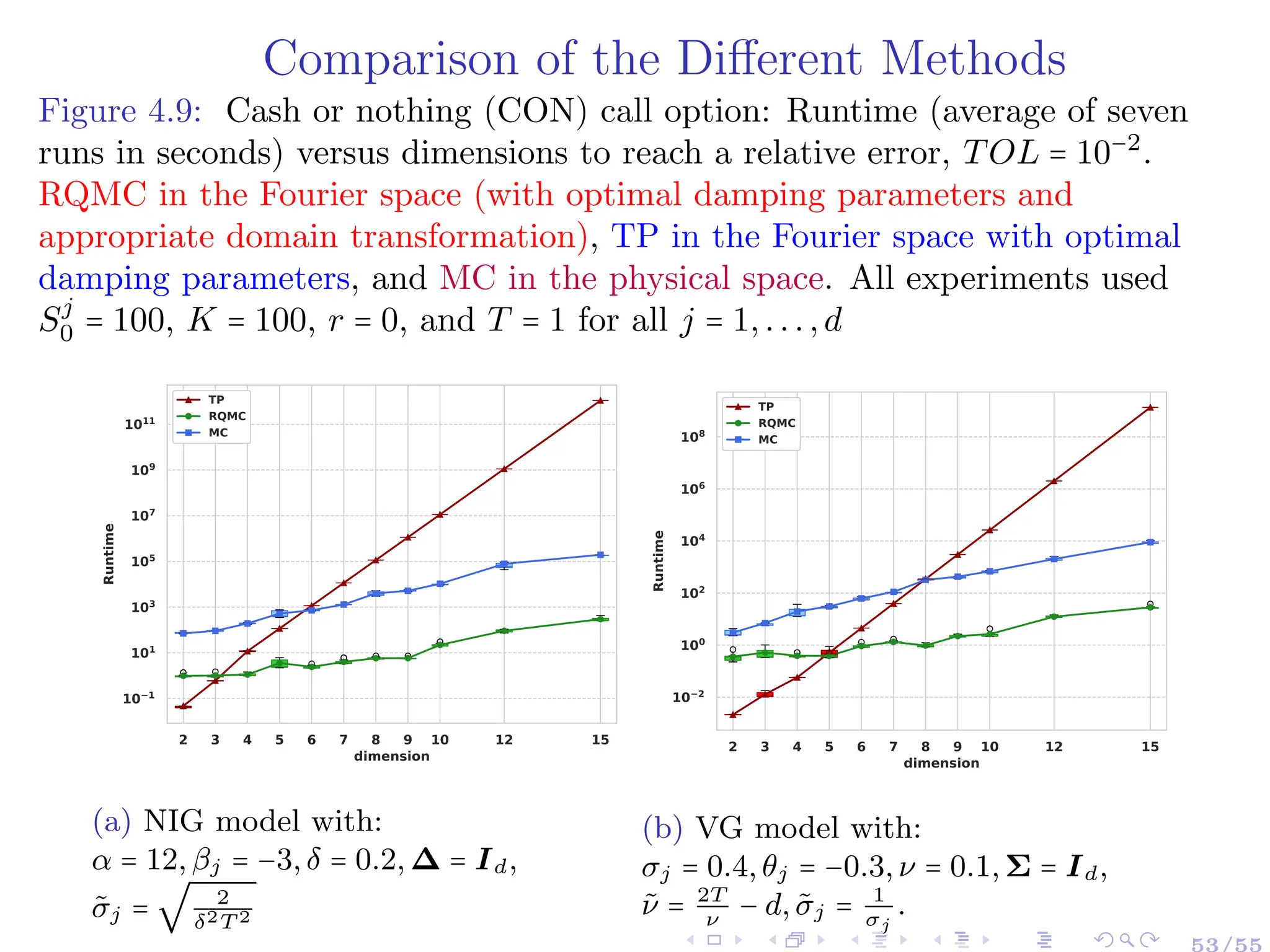

The document discusses efficient pricing methods for high-dimensional derivatives using Fourier-based techniques. It highlights challenges such as the non-smoothness of payoff functions and large dimensions, proposing solutions like mapping to Fourier space and using quasi-Monte Carlo methods. Key findings and methodologies are summarized based on collaborative research involving multiple authors and related works.

![Framework and Problem Setting

Task: Compute efficiently (up to a discount factor)

E[P(X(T)) ∣ X(0) = x0] = ∫

Rd

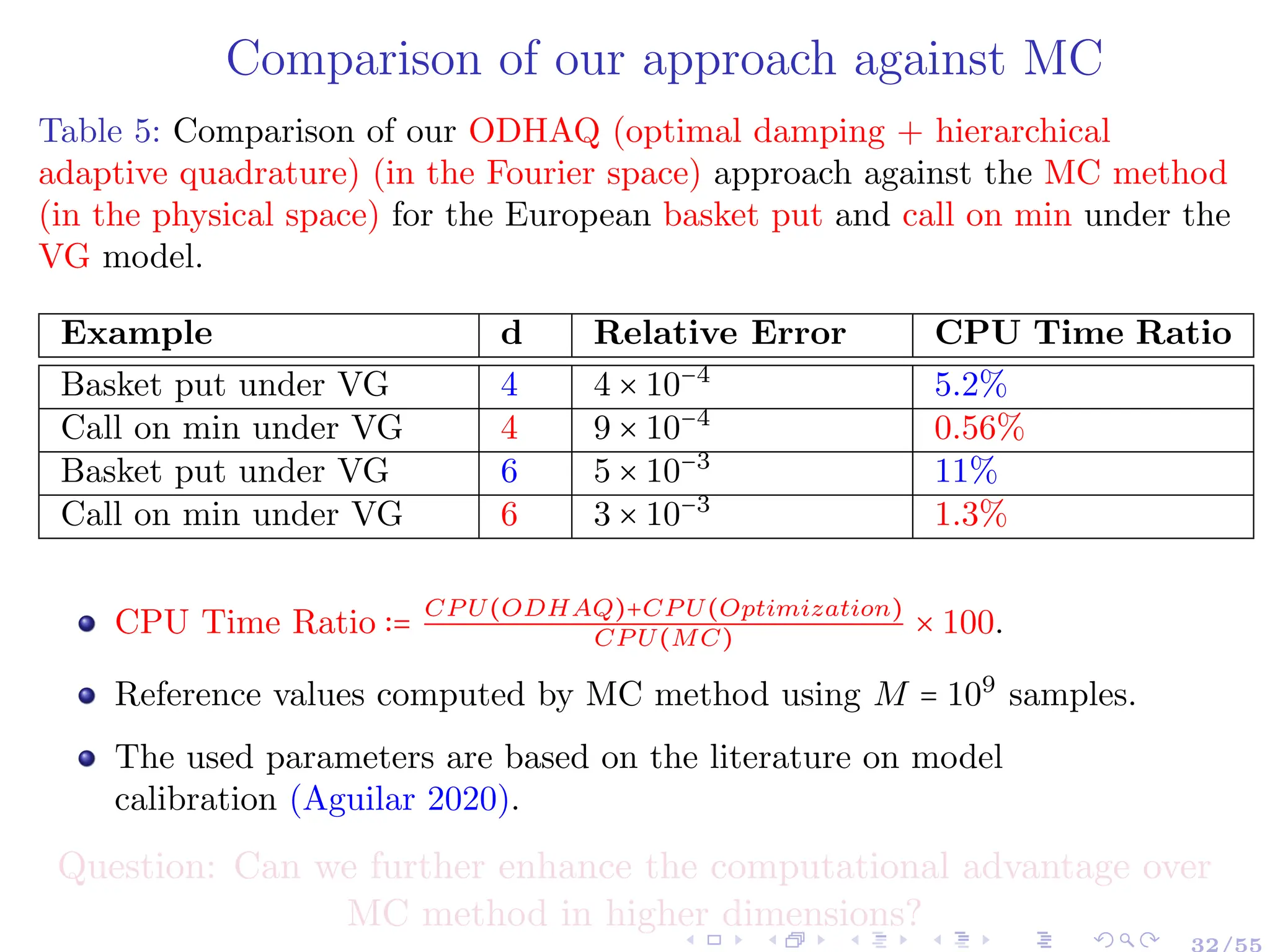

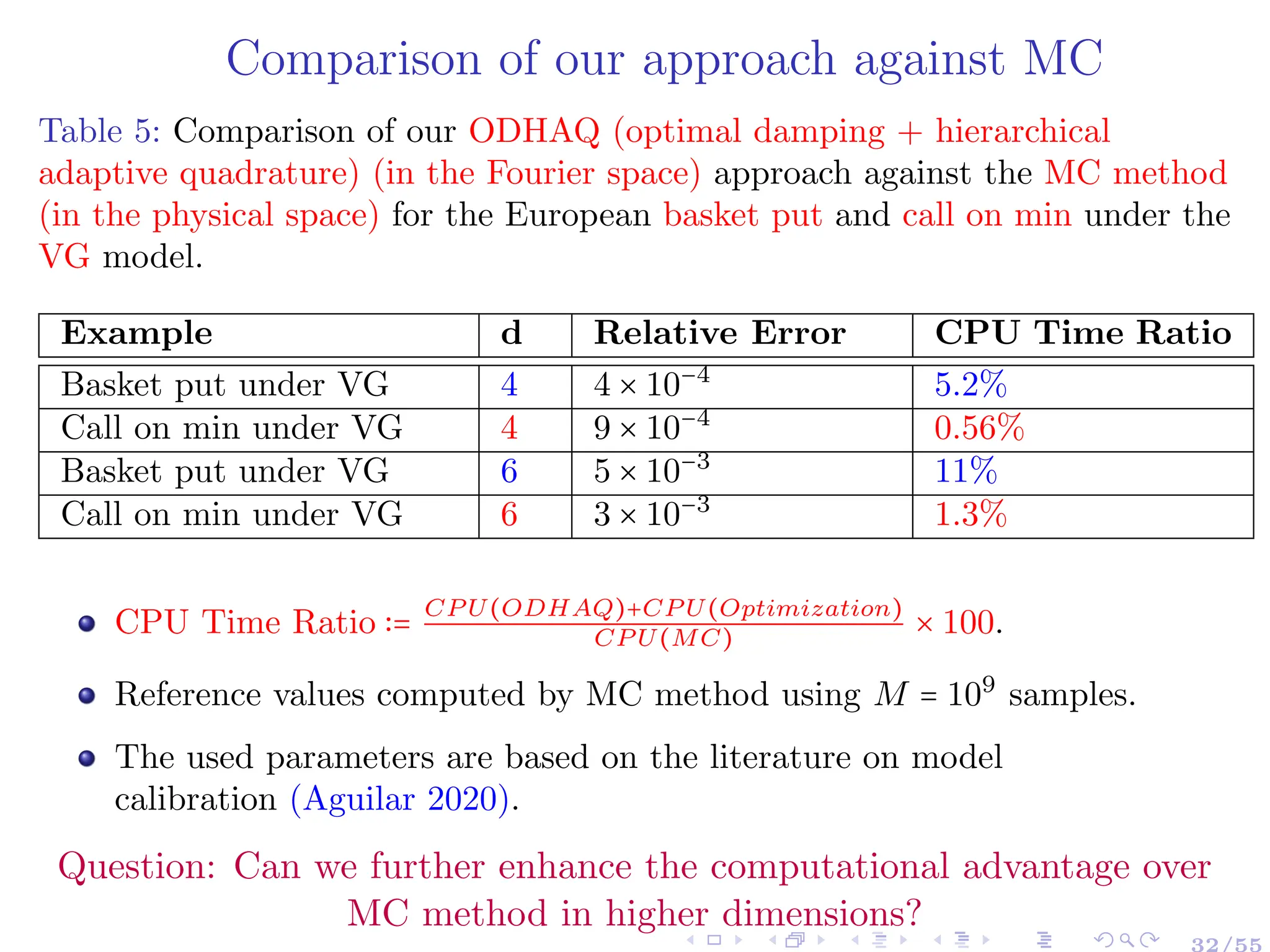

P(x) ρXT ∣x0

(x) dx

▸ P ∶ Rd

→ R: payoff function

▸ {Xt ∈ Rd

∶ t ≥ 0}: stochastic processes representing the log-prices of

the underlying assets (resp. risk factors) at time t, defined on a

continuous-time probability space (Ω,F,Q), with Q is the

risk-neutral measure.

Applications in Mathematical Finance: Computing the value

of derivatives (resp. risk measures) depending on multiple assets

(resp. risk factors) and their sensitivities (Greeks).

Features of the problem

P(⋅) is non-smooth.

The dimension d is large.

The pdf, ρXT

, is not known explicitly or expensive to

sample from.

3/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-5-2048.jpg)

![Task ((Multi-Asset) Option Pricing and Beyond): Compute efficiently (up to a

discount factor)

E[P(X(T)) ∣ X(0) = x0] = ∫

Rd

P(x) ρXT ∣x0

(x) dx

Setting: Payoff Function

P(⋅): payoff function (typically non-smooth), e.g., (K: the strike price)

▸ Basket put: P(x) = max(K − ∑

d

i=1 ciexi

,0), s.t. ci > 0,∑

d

i=1 ci = 1;

▸ Rainbow (E.g., Call on min): P(x) = max(min(ex1

,...,exd

) − K,0)

▸ Cash-or-nothing (CON) put : P(x) = ∏

d

i=1 1[0,Ki](exi

).

x1

4

2

0

2

4

x

2

4

2

0

2

4

P(x

1

,

x

2

)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

(a) Basket put

x1

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

x

2

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

P

(

x

1

,

x

2

)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

1.4

1.6

(b) Call on min

x1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

x

2

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

P(x

1

,

x

2

)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

(c) Cash-or-nothing

Figure 1.1: Payoff functions illustration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-6-2048.jpg)

![Task ((Multi-Asset) Option Pricing and Beyond): Compute efficiently (up to

a discount factor)

E[P(X(T)) ∣ X(0) = x0] = ∫

Rd

P(x) ρXT ∣x0

(x) dx

Setting: Asset Price Model

XT is a d-dimensional (d ≥ 1) vector of log-asset prices at time T,

following a multivariate stochastic model:

▸ Characteristic function, ΦXT

(⋅) ∶= EρXT

[ei⟨⋅,XT ⟩

],

can be known (semi-)analytically or approximated numerically,

e.g,.

☀ Lévy models (Cont et al. 2003): Characteristic function obtained

via Lévy–Khintchine representation.

☀ Affine processes (Duffie et al. 2003): Characteristic function

obtained via Ricatti Equations.

▸ The pdf, ρXT

, is

☀ not known explicitly (e.g. α-stable Lévy processes

(0 < α ≤ 2, α ≠ {1, 1

2

, 2}) (Eberlein 2009)), or

☀ expensive to sample from (e.g. non-Markovian models such

as rough Heston (El Euch et al. 2019)).

5/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-7-2048.jpg)

![Numerical Integration Methods

Task ((Multi-Asset) Option Pricing and Beyond): Compute

efficiently (up to discount factor)

E[P(X(T)) ∣ X(0) = x0] = ∫

Rd

P(x) ρXT ∣x0

(x) dx

Features of the problem

P(⋅) is non-smooth.

The dimension d is large.

The pdf, ρXT

, is not known explicitly or expensive to

sample from.

Challenges

1 Monte Carlo method has a convergence rate independent of the

problem’s dimension and integrand’s regularity BUT can be very slow.

2 non-smoothness of P(⋅) and the high dimensionality ⇒ deteriorated

convergence of deterministic quadrature methods.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-9-2048.jpg)

![Numerical Integration Methods: Sampling in [0,1]2

E[P(X(T))] = ∫Rd P(x)ρXT

(x)dx ≈ ∑

M

m=1 ωmP (Ψ(um)) (Ψ ∶ [0,1]d

→ Rd

).

Monte Carlo (MC)

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

u1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

u2

Tensor Product Quadrature

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

u1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

u2

Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC)

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

u1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

u2

Adaptive Sparse Grids Quadrature

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

u1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

u2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-10-2048.jpg)

![Fourier Pricing Formula in d Dimensions

Assumption 2.1

1 x ↦ P(x) is continuous on Rd

(can be replaced by additional assumptions on XT ).

2 δP ∶= {R ∈ Rd

∶ x ↦ eR′x

P(x) ∈ L1

bc(Rd

) and y ↦ ̂

P(y + iR) ∈ L1

(Rd

)} ≠ ∅.

(strip of analyticity of ̂

P(⋅))

3 δX ∶= {R ∈ Rd

∶ y ↦∣ ΦXT

(y + iR) ∣< ∞,∀ y ∈ Rd

} ≠ ∅. (strip of analyticity of ΦXT (⋅))

Proposition (Ben Hammouda et al. 2023 (Extension of (Lewis 2001) in 1D and based on

(Eberlein et al. 2010))

Under Assumptions 1, 2 and 3, and for R ∈ δV ∶= δP ∩ δX, the option value on d stocks is

V (ΘX,Θp) ∶= e−rT

E[P(XT)] = ∫

Rd

P(x) ρXT

(x) dx (1)

= (2π)−d

e−rT

∫

Rd

R(ΦXT

(y + iR) ̂

P(y + iR))dy.

Notation

ΘX,Θp: the model and payoff parameters, respectively;

̂

P(⋅): the extended Fourier transform of the payoff P(⋅) ( ̂

P(z) ∶= ∫Rd e−iz′

⋅x

P(x)dx, for z ∈ Cd

);

XT : vector of log-asset prices at time T, with extended characteristic function ΦXT

(⋅) (i.e.,

Φ ∶= ̂

ρ);

R ∈ Rd

: damping parameters ensuring integrability and controlling the integration contour.

R[⋅]: real part of the argument. i: imaginary unit. 12/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-15-2048.jpg)

![Fourier Pricing Formula in d Dimensions

Proof (Ben Hammouda et al. 2023).

Using the inverse generalized Fourier transform and Fubini theorems:

V (ΘX,ΘP ) = e−rT

E[P(XT)]

= e−rT

E[(2π)−d

R(∫

Rd

ei(y+iR)′

XT ̂

P(y + iR)dy)], R ∈ δP

= (2π)−d

e−rT

R(∫

Rd

E[ei(y+iR)′

XT

] ̂

P(y + iR)dy), R ∈ δV ∶= δP ∩ δX

= (2π)−d

e−rT

∫

Rd

R(ΦXT

(y + iR) ̂

P(y + iR))dy, R ∈ δV

Notation 2.2 (Integrand)

Given R ∈ δV ⊆ Rd

, we define the integrand of interest by

g (y;R,ΘX,ΘP ) ∶= (2π)−d

e−rT

R[ΦXT

(y + iR) ̂

P(y + iR)], y ∈ Rd

, (2)

13/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-16-2048.jpg)

![Characteristic Functions: Illustrations

Table 1: ΦXT

(z) = exp(iz′

(X0 + (r + µ)T))ϕXT

(z): extended characteristic function of various

pricing models. I[⋅]: the imaginary part of the argument. Kλ(⋅) is the Bessel function of the

second kind. GH coincides with NIG for λ = −1

2

.

Model ϕXT

(z),z ∈ Cd

, I[z] ∈ δX

GBM exp(−T

2

z′

Σz)

VG (1 − iνz′

θ + 1

2

νz′

Σz)

−T /ν

GH ( α2

−β⊺

∆β

α2−β⊺

∆β+z⊺∆z−2iβ⊺

∆z

)

λ/2 Kλ(δT

√

α2−β⊺

∆β+z⊺∆z−2iβ⊺

∆z)

Kλ(δT

√

α2−β⊺

∆β)

NIG exp(δT (

√

α2 − β′

∆β −

√

α2 − (β + iz)′∆(β + iz)))

Table 2: Strip of analyticity, δX, of ΦXT

(⋅) (Eberlein et al. 2010)

Model δX

GBM Rd

VG {R ∈ Rd

,(1 + νθ′

R − 1

2

νR′

ΣR) > 0}

GH, NIG {R ∈ Rd

,(α2

− (β − R)′

∆(β − R)) > 0}

Notation:

Σ: Covariance matrix for the Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) model.

ν > 0, θ, σ, Σ: Variance Gamma (VG) model parameters.

α, δ > 0, β, ∆: Normal Inverse Gaussian (NIG) and Generalized Hyperbolic (GH) model parameters.

µ: martingale correction terms depending on the model parameters.

14/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-17-2048.jpg)

![Payoff Fourier Transforms: Illustration

Table 3: Fourier Transforms of (scaled) Payoff Functions, z ∈ Cd

. Γ(z) is the

complex Gamma function defined for z ∈ C with R[z] > 0.

Payoff P(XT ) ̂

P(z)

Basket put max(1 − ∑d

i=1 eXi

T ,0)

∏d

j=1 Γ(−izj)

Γ(−i ∑d

j=1 zj+2)

Call on min max(min(eX1

T ,...,eXd

T ) − 1,0) 1

(i(∑d

j=1 zj)−1) ∏d

j=1(izj)

CON put ∏d

j=1 1

{e

X

j

T <1 }

(Xj

T ) ∏d

j=1 (− 1

izj

)

Table 4: Strip of analyticity, δP , of ̂

P(⋅).

Payoff δP

Basket put {R ∈ Rd

,Ri > 0 ∀i ∈ {1,...,d}}

Call on min {R ∈ Rd

, Ri < 0 ∀i ∈ {1...d}, ∑d

i=1 Ri < −1}

CON put {Rj > 0}

15/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-18-2048.jpg)

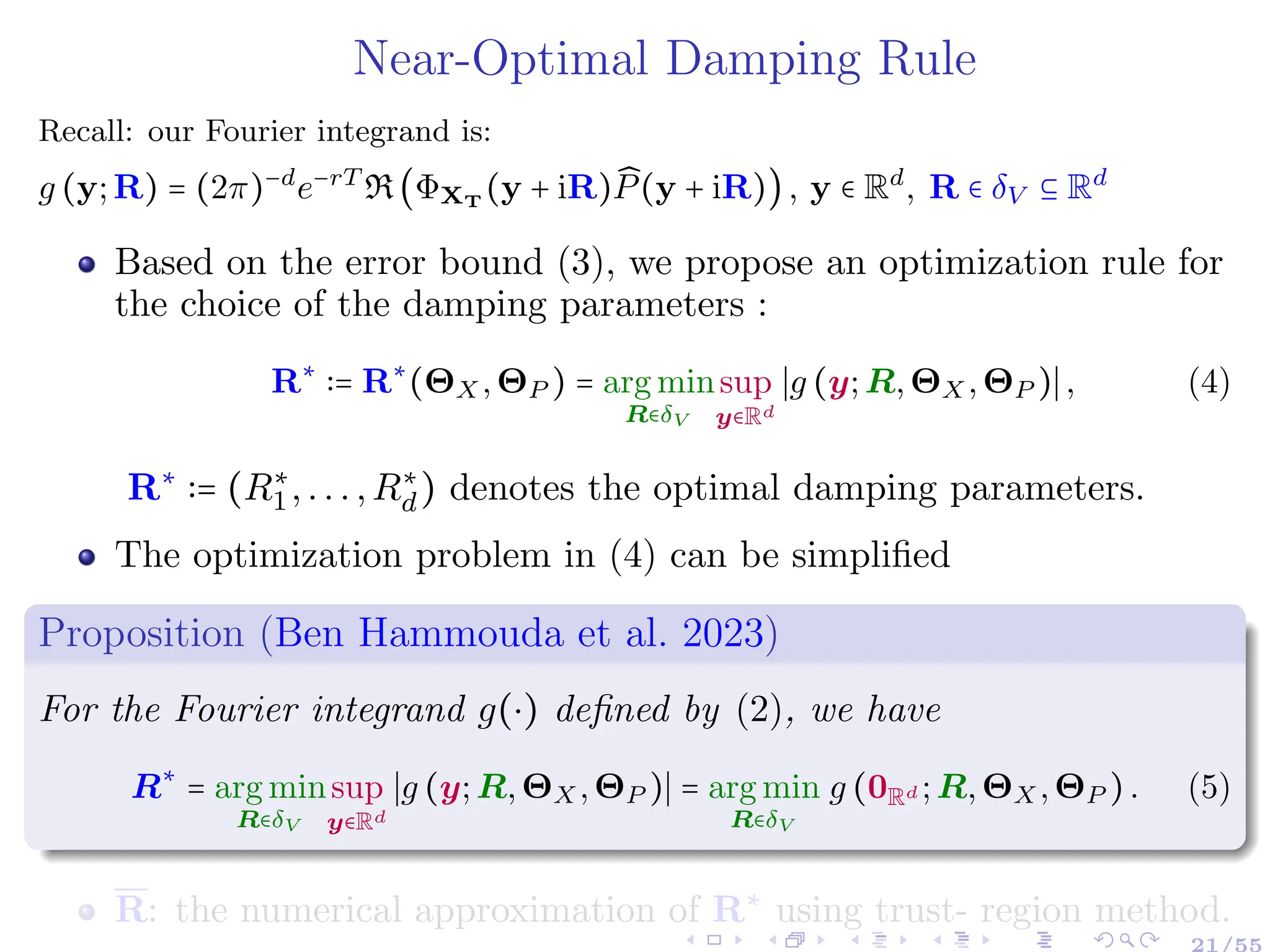

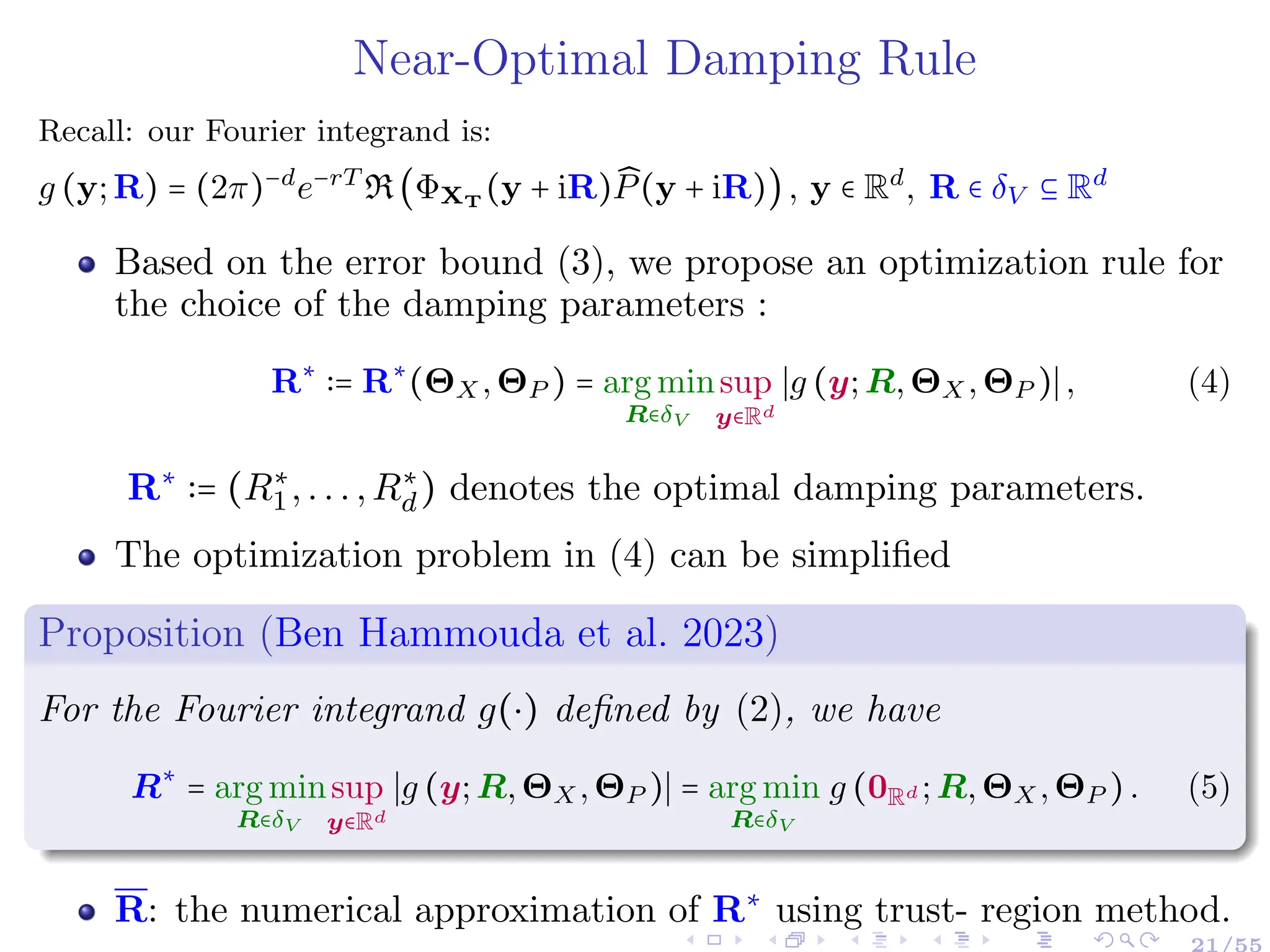

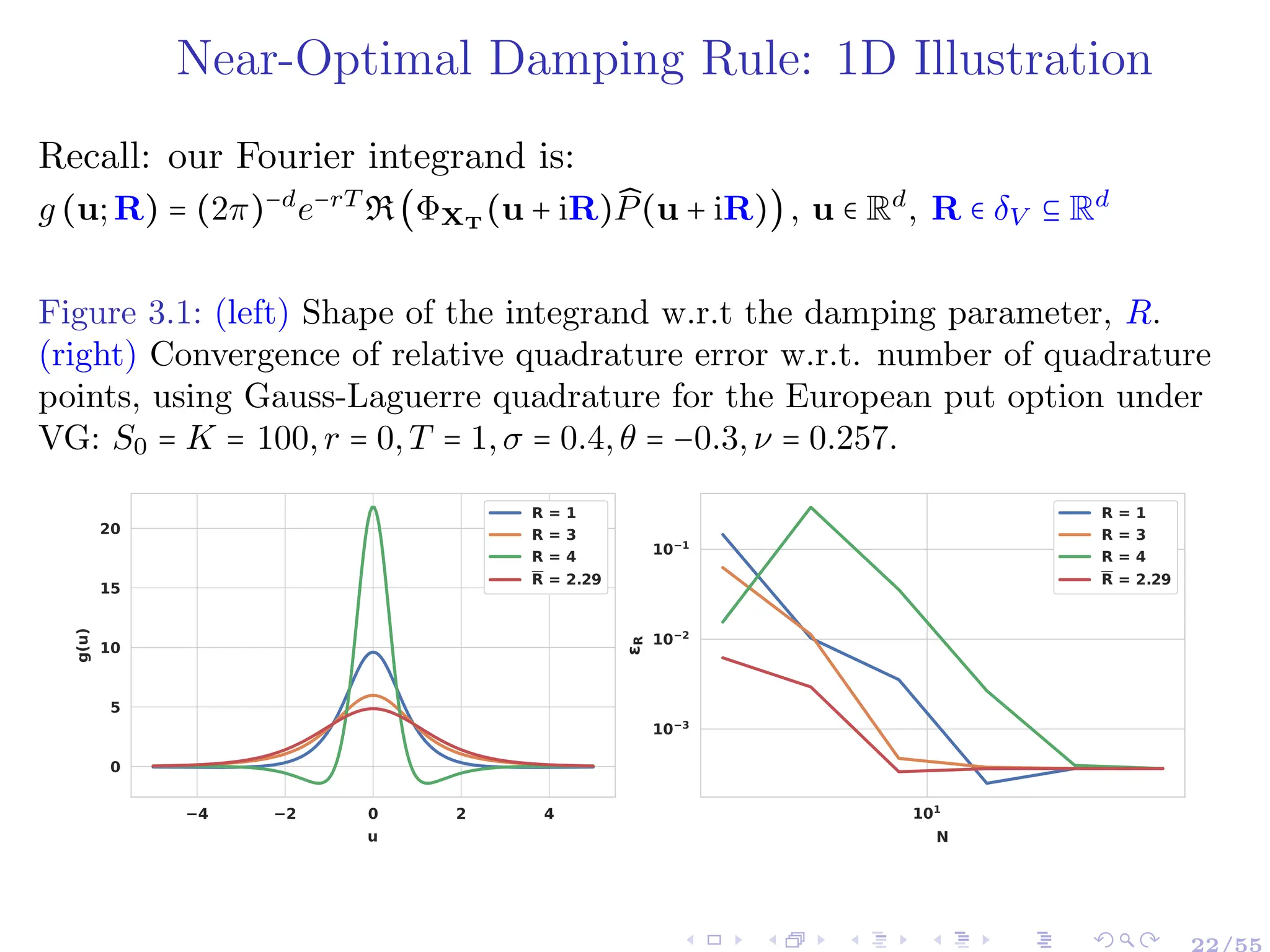

![Near-Optimal Damping Rule: Theoretical Argument

Theorem 3.1 (Error Estimate Based on Contour Integration)

Assuming f can be extended analytically along a sizable contour, C ⊇ [a,b], in

the complex plane, and f has no singularities in C, then we have,

∣EQN

[f]∣ ∶= ∣∫

b

a

f(x)λ(x)dx −

N

∑

k=1

f (xk)wk∣

= ∣

1

2πi

∮

C

KN (z)f(z)dz∣ ≤

1

2π

sup

z∈C

∣f(z)∣∮

C

∣KN (z)∣dz,

(3)

(Ben Hammouda et al. 2023) proves the extension to the

multivariate setting.

Notation:

KN (z) =

HN (z)

πN (z) , HN (z) = ∫

b

a λ(x)

πN (x)

z−x dx.

πN (⋅): the roots of the orthogonal polynomial related to the considered

quadrature with weight function λ(⋅).

20/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-24-2048.jpg)

![Option value on d stocks

(Multivariate Expectation of Interest)

Recall: our Fourier integrand is:

g (y;R) = (2π)−d

e−rT

R(ΦXT

(y + iR) ̂

P(y + iR)), y ∈ Rd

, R ∈ δV ⊆ Rd

Physical space:

E[P(X(T))] =

∫Rd P(x) ρXT

(x) dx

A non-smooth

d-dimensional

integration problem

Fourier space:

∫Rd g (y;R)dy

A highly-smooth

d-dimensional

integration problem

Fourier Mapping

+ Damping Rule](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-29-2048.jpg)

![Quadrature Methods: Illustration of Grids Construction

Figure 3.3: N = 81 Clenshaw-Curtis quadrature points on [0,1]2

for (left) TP,

(center) sparse grids, (right) adaptive sparse grids quadrature

(ASGQ). The ASGQ is built for the function: f(u1,u2) = 1

u2

1+exp(10 u2)+0.3

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

u1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

u2

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

u1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

u2

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

u1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

u2

25/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-32-2048.jpg)

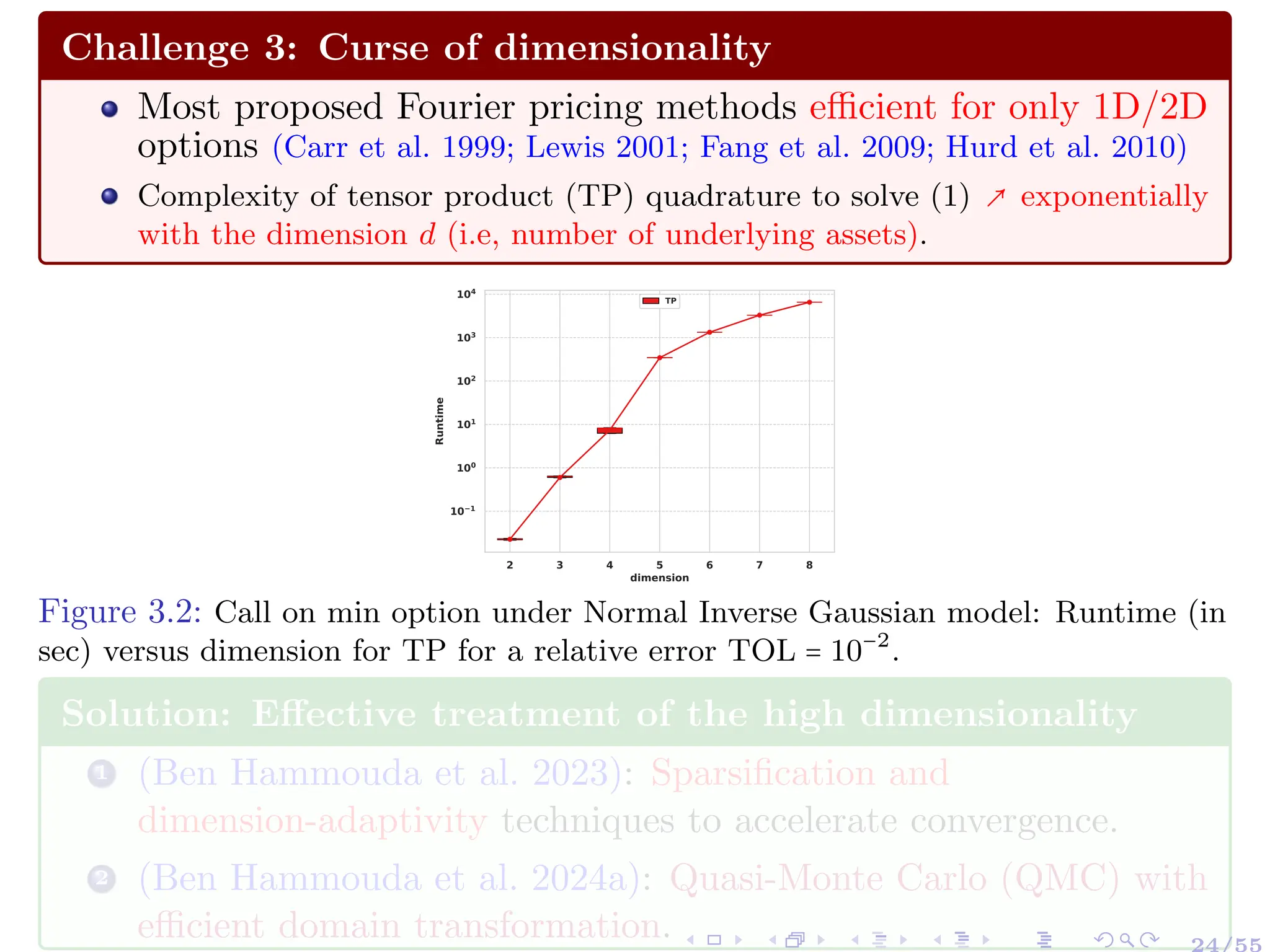

![Quadrature Methods

Naive Quadrature operator based on a Cartesian quadrature grid

∫

Rd

g(x)ρ(x)dx ≈

d

⊗

k=1

QNk

k [g] ∶=

N1

∑

i1=1

⋯

Nd

∑

id=1

wi1 ⋯wid

g (xi1 ,...,xid

)

" Caveat: Curse of dimension: i.e., total number of quadrature

points N = ∏d

k=1 Nk.

Solution:

1 Sparsification of the grid points to reduce computational work.

2 Dimension-adaptivity to detect important dimensions of the

integrand.

Notation:

{xik

,wik

}Nk

ik=1 are respectively the sets of quadrature points and

corresponding quadrature weights for the kth dimension, 1 ≤ k ≤ d.

QNk

k [.]: the univariate quadrature operator for the kth dimension.

26/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-33-2048.jpg)

![1D Hierarchical Construction of Quadrature Methods

Let m(⋅) ∶ N+ → N+ be a strictly increasing function with m(1) = 1;

▸ β ∈ N+: hierarchical quadrature level.

▸ m(β) ∈ N+: number of quadrature points used at level β.

Hierarchical construction: example for level 3 quadrature Qm(3)

[g]:

Qm(3)

[g] = Qm(1)

´¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¶

∆m(1)

[g] + (Qm(2)

− Qm(1)

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

∆m(2)

)[g] + (Qm(3)

− Qm(2)

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

∆m(3)

)[g],

where ∆m(β)

∶= Qm(β)

− Qm(β−1)

, Qm(0)

= 0: univariate detail operator.

The exact value of the integral can be written as a series expansion of

detail operators

∫

R

g(x)dx =

∞

∑

β=1

∆m(β)

[g],

27/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-34-2048.jpg)

![Hierarchical Sparse grids: Construction

Let β = [β1,...,βd] ∈ Nd

+, m(β) ∶ N+ → N+ an increasing function,

1 1D quadrature operators: Q

m(βk)

k on m(βk) points, 1 ≤ k ≤ d.

2 Detail operator: ∆

m(βk)

k = Q

m(βk)

k − Q

m(βk−1)

k , Q

m(0)

k = 0.

3 Hierarchical surplus: ∆m(β)

= ⊗d

k=1 ∆

m(βk)

k .

4 Hierarchical sparse grid approximation: on an index set I ⊂ Nd

QI

d [g] = ∑

β∈I

∆m(β)

[g] (6)

28/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-35-2048.jpg)

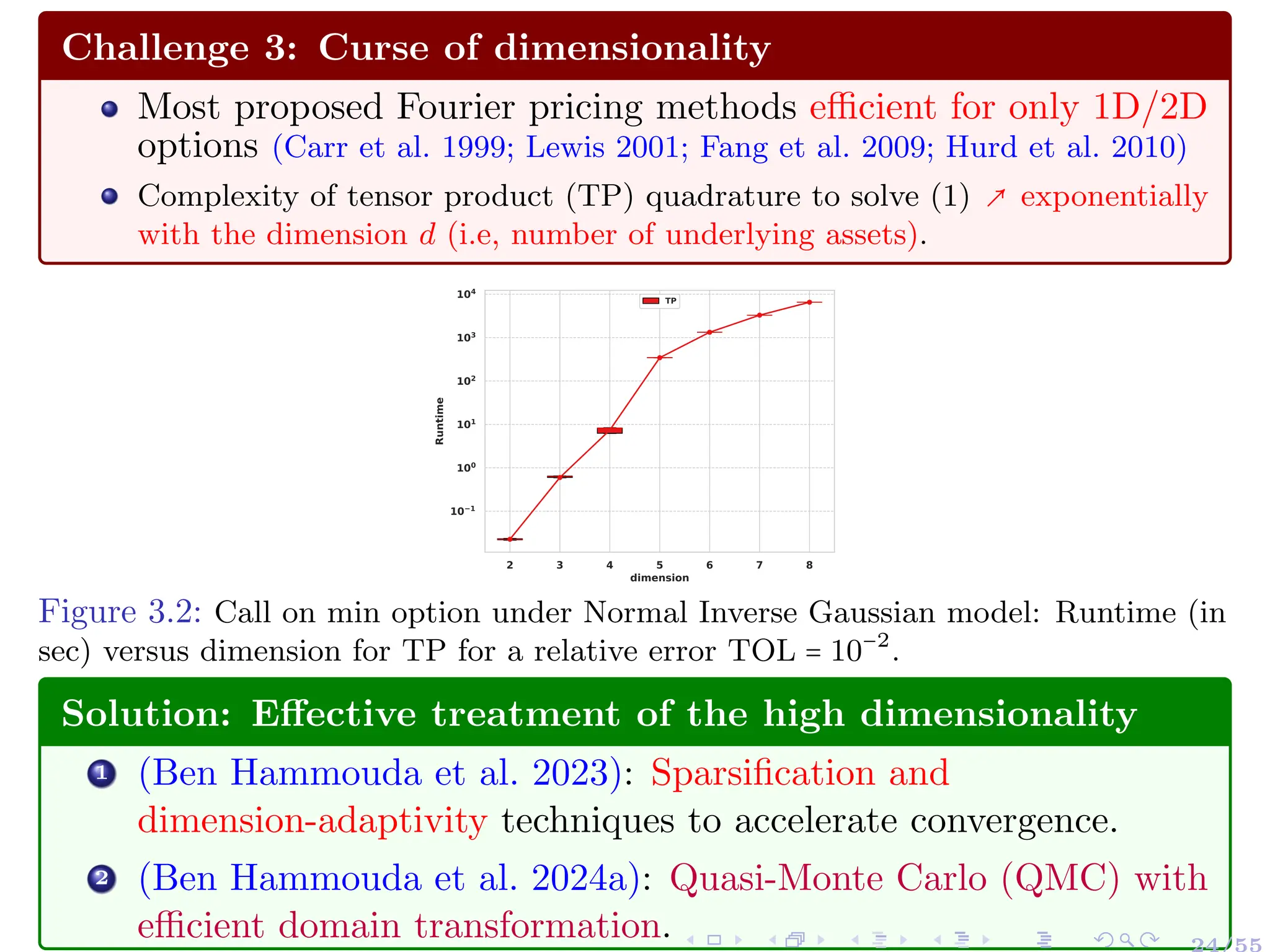

![Grids Construction

Tensor Product (TP) approach: I ∶= Iℓ = {∣∣ β ∣∣∞≤ ℓ; β ∈ Nd

+}.

Regular sparse grids (SG): I ∶ Iℓ = {∣∣ β ∣∣1≤ ℓ + d − 1; β ∈ Nd

+}

Adaptive sparse grids (ASG): Adaptive and a posteriori

construction of I = IASGQ

by profit rule

IASGQ

= {β ∈ Nd

+ ∶ Pβ ≥ T}, with Pβ =

∣∆Eβ∣

∆Wβ

:

▸ ∆Eβ = ∣Q

I∪{β}

d [g] − QI

d [g]∣ (error contribution);

▸ ∆Wβ = Work[Q

I∪{β}

d [g]] − Work[QI

d [g]] (work contribution).

Figure 3.4: 2-D Illustration (Chen 2018): Admissible index sets I (top) and

corresponding quadrature points (bottom). Left: TP; middle: SG; right: ASG .

29/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-36-2048.jpg)

![Quasi Monte Carlo methods and Discrepancy

Let P = {ξ1,...ξM } be a set of points ξi ∈ [0,1]N

and f ∶ [0,1]N

→ R a

continuous function. A Quasi Monte Carlo (QMC) method to

approximate IN (f) = ∫[0,1]N f(y)dy is an equal weight cubature

formula of the form

IN,M (f) =

1

M

M

∑

i=1

f(ξi) .

The key concept in the analysis of QMC methods is the one of

discrepancy. Notation: for x ∈ [0,1]N

let

[0,x] ∶= [0,x1] × ... × [0,xN ]. Then

V ol([0,x]) ≈ ̂

V olP ([0,x]) ∶=

# points in [0,x]

M

for a given point set P = {ξ1,...ξM }.

Local discrepancy function ∆P ∶[0,1]N

→ [−1,1]

∆P (x) ∶= ̂

V olP ([0,x]) − V ol([0,x])

=

1

M

M

∑

i=1

1[0,x](ξi) −

N

∏

i=1

xi

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

000000000000000

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

111111111111111

x

33/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-42-2048.jpg)

![Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC):

Need for Domain Transformation

Recall: our Fourier integrand is:

g (y;R) = (2π)−d

e−rT

R(ΦXT

(y + iR) ̂

P(y + iR)), y ∈ Rd

, R ∈ δV ⊂ Rd

Our Fourier integrand is in Rd

BUT QMC constructions are restricted

to the generation of low-discrepancy point sets on [0,1]d

.

0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1

u1

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

u2

Figure 4.1: shifted QMC (Lattice rule) low discrepancy points (LDP)

in 2D

⇒ Need to transform the integration domain

34/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-43-2048.jpg)

![Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC):

Need for Domain Transformation

Recall: our Fourier integrand is:

g (y;R) = (2π)−d

e−rT

R(ΦXT

(y + iR) ̂

P(y + iR)), y ∈ Rd

, R ∈ δV ⊂ Rd

Our Fourier integrand is in Rd

BUT QMC constructions are restricted

to the generation of low-discrepancy point sets on [0,1]d

.

⇒ Need to transform the integration domain

Compositing with inverse cumulative distribution function, we obtain

∫

Rd

g(y)dy = ∫

[0,1]d

g ○ Ψ−1

(u;Λ)

ψ ○ Ψ−1(u;Λ)

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

=∶g̃(u;Λ)

du.

▸ ψ(⋅;Λ): a probability density function (PDF) with parameters Λ.

▸ Ψ(⋅;Λ): the cumulative distribution function (CDF) corresponding

to ψ(⋅;Λ).

34/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-44-2048.jpg)

![Randomized Quasi-Monte Carlo (RQMC)

The transformed integration problem reads now:

∫

[0,1]d

g ○ Ψ−1

(u;Λ)

ψ ○ Ψ−1(u;Λ)

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

=∶g̃(u;Λ)

du. (7)

Once the choice of ψ(⋅;Λ) (respectively Ψ−1

(⋅;Λ)) is determined,

the RQMC estimator of (7) can be expressed as follows:

QRQMC

N,S [g̃] ∶=

1

S

S

∑

i=1

1

N

N

∑

n=1

g̃ (u(s)

n ;Λ), (8)

▸ {un}N

n=1 is the sequence of deterministic QMC points in [0,1]d

▸ For n = 1,...,N, {u

(s)

n }S

s=1: obtained by an appropriate

randomization of {un}N

n=1, e.g.,

u

(s)

n = {un + ηs}, with {ηs}S

s=1

i.i.d

∼ U([0,1]d

) and {⋅} is the

modulo-1 operator.

35/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-45-2048.jpg)

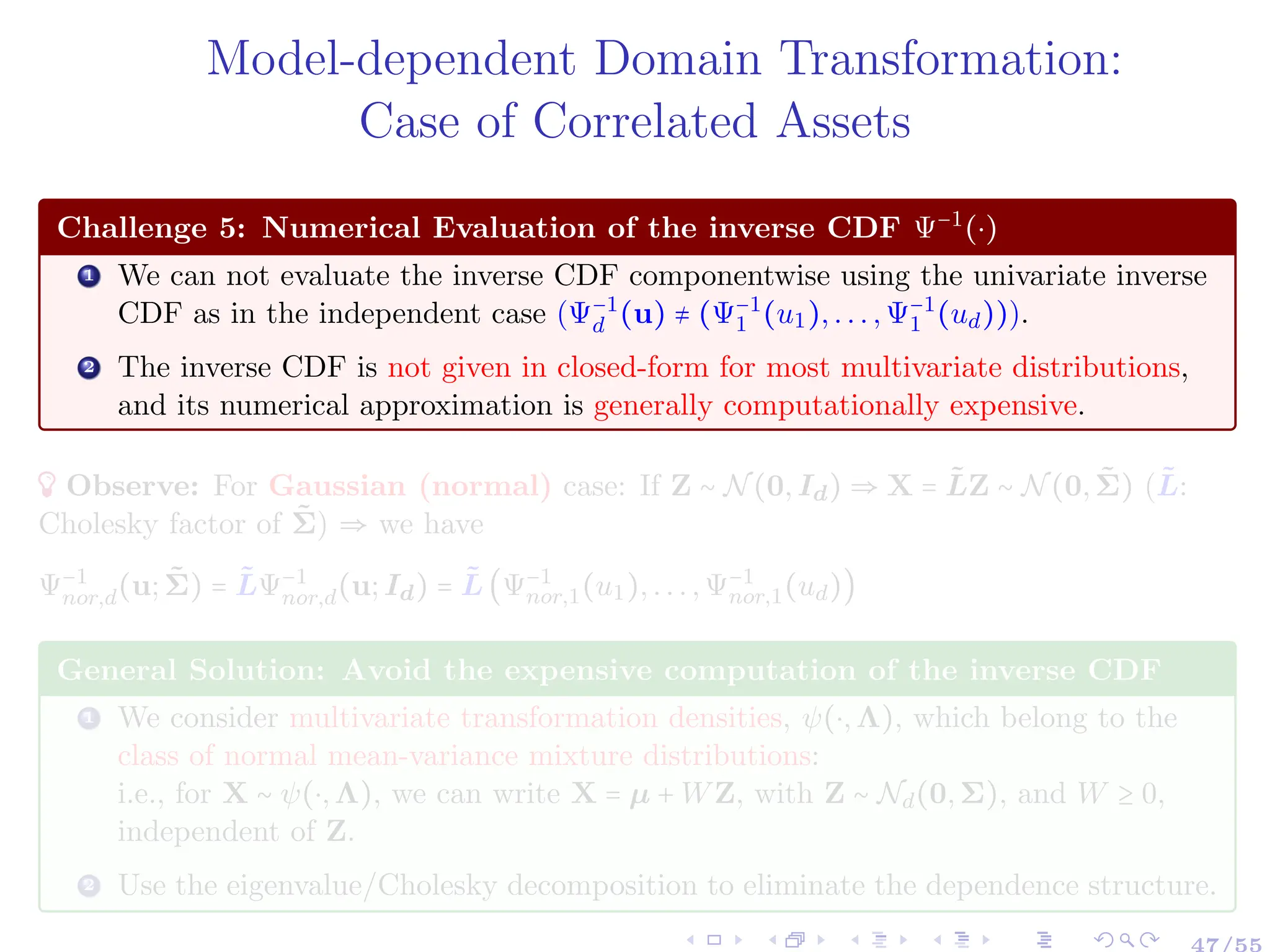

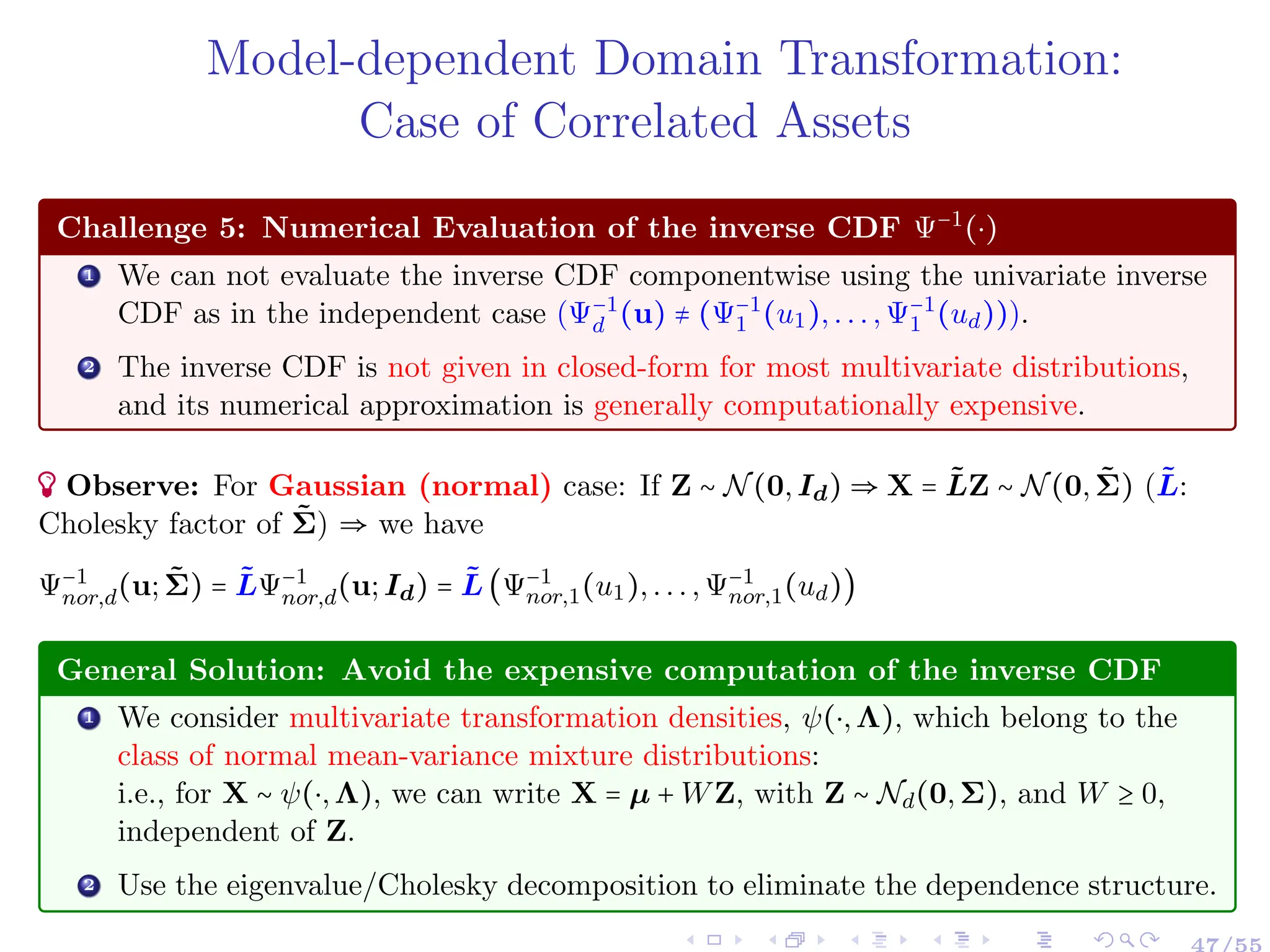

![Previous literature (Kuo et al. 2011; Nichols et al. 2014; Ouyang et al.

2023) considers a different setting (more straightforward) for QMC:

Transformation for a weighted integration problem

(i.e., ∫Rd g(y) ρ(y) dy),

In the physical space

Assumes an independence structure

Our Setting

Recall the transformed integration problem in the Fourier space

∫

[0,1]d

g ○ Ψ−1

(u;Λ)

ψ ○ Ψ−1(u;Λ)

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

=∶g̃(u;Λ)

du.

⇒ We need to design a transformation adapted to our setting and take

into account possible dependencies between the dimensions (i.e.,

correlation between asset prices). 36/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-46-2048.jpg)

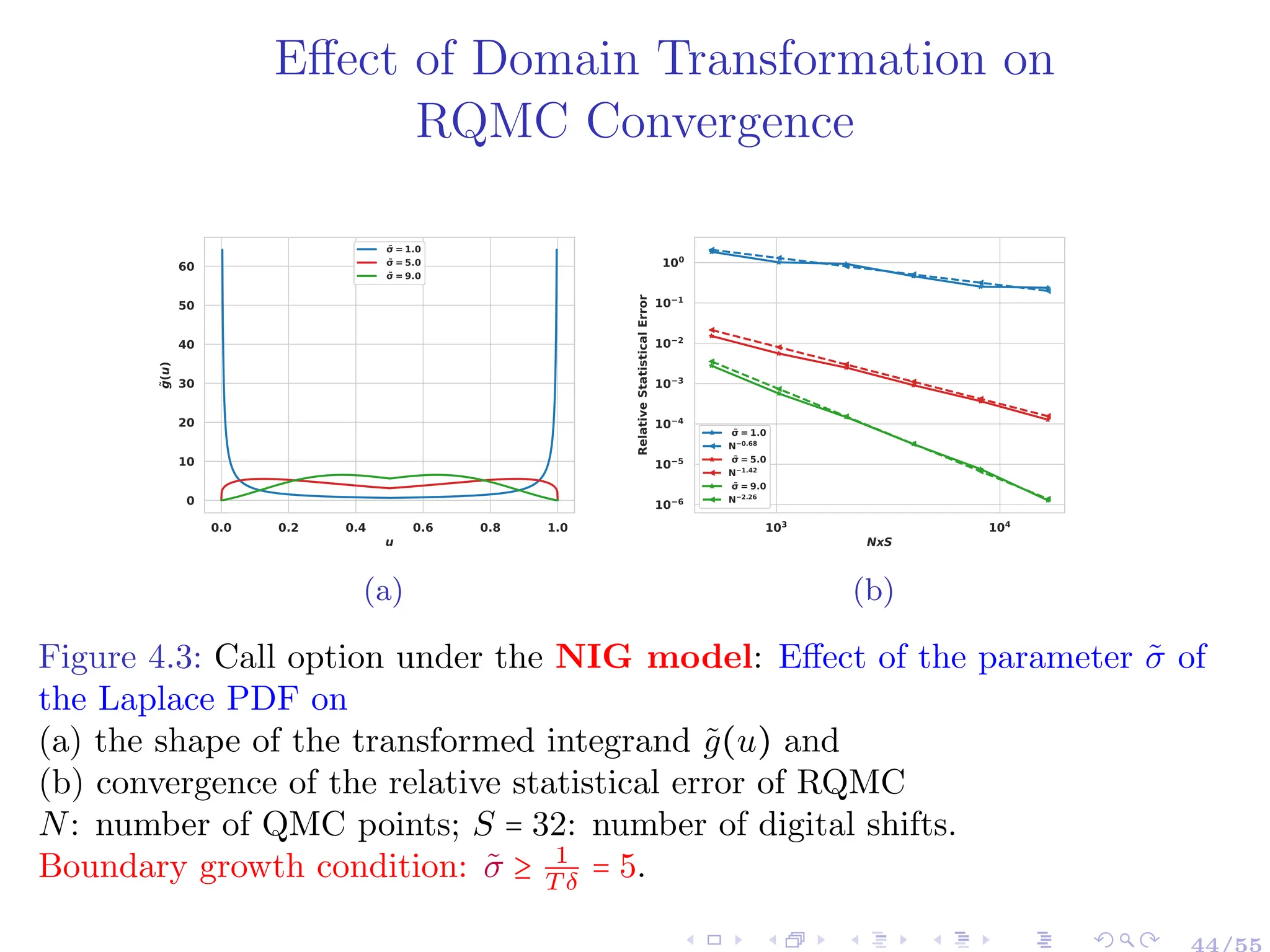

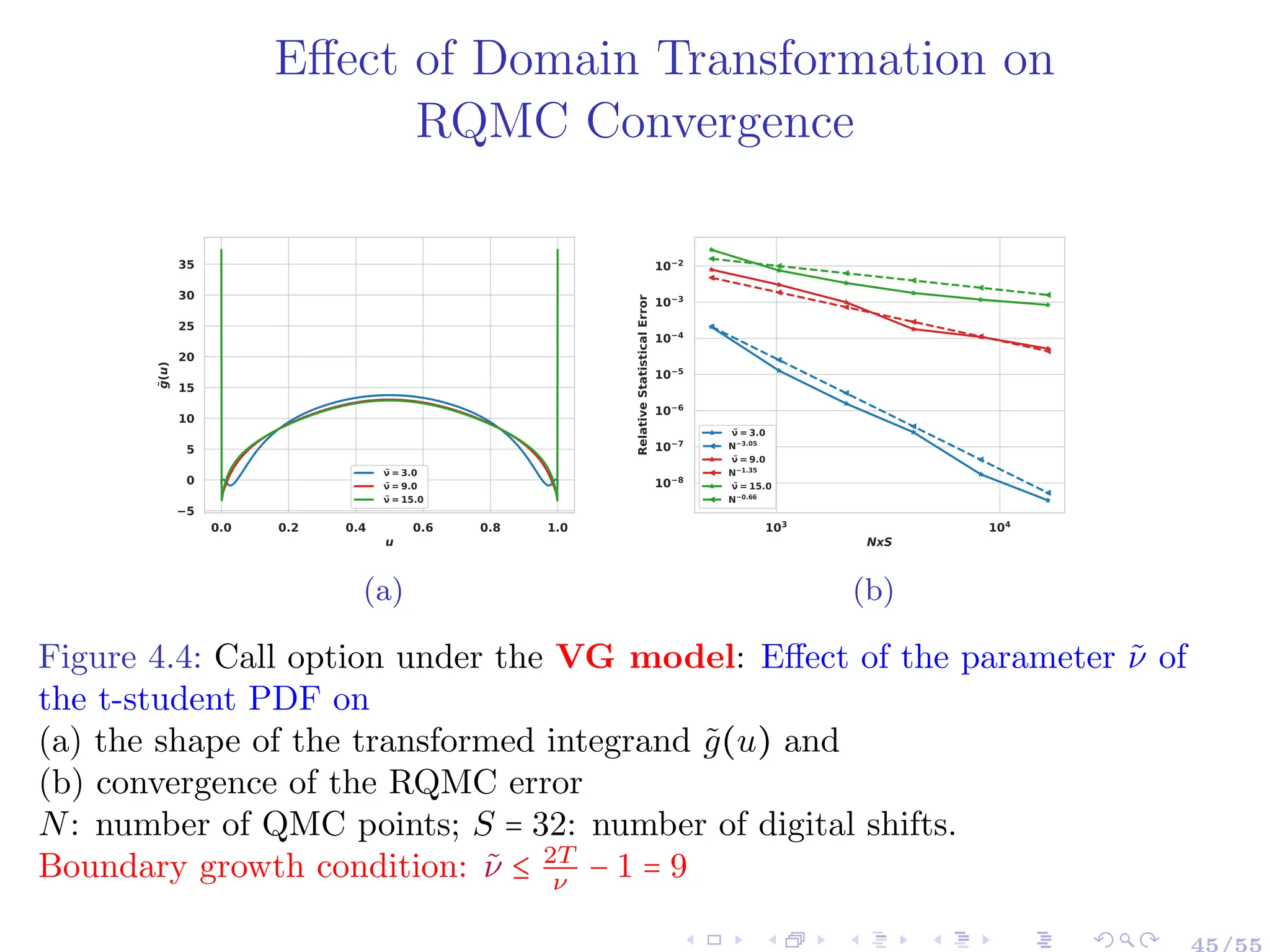

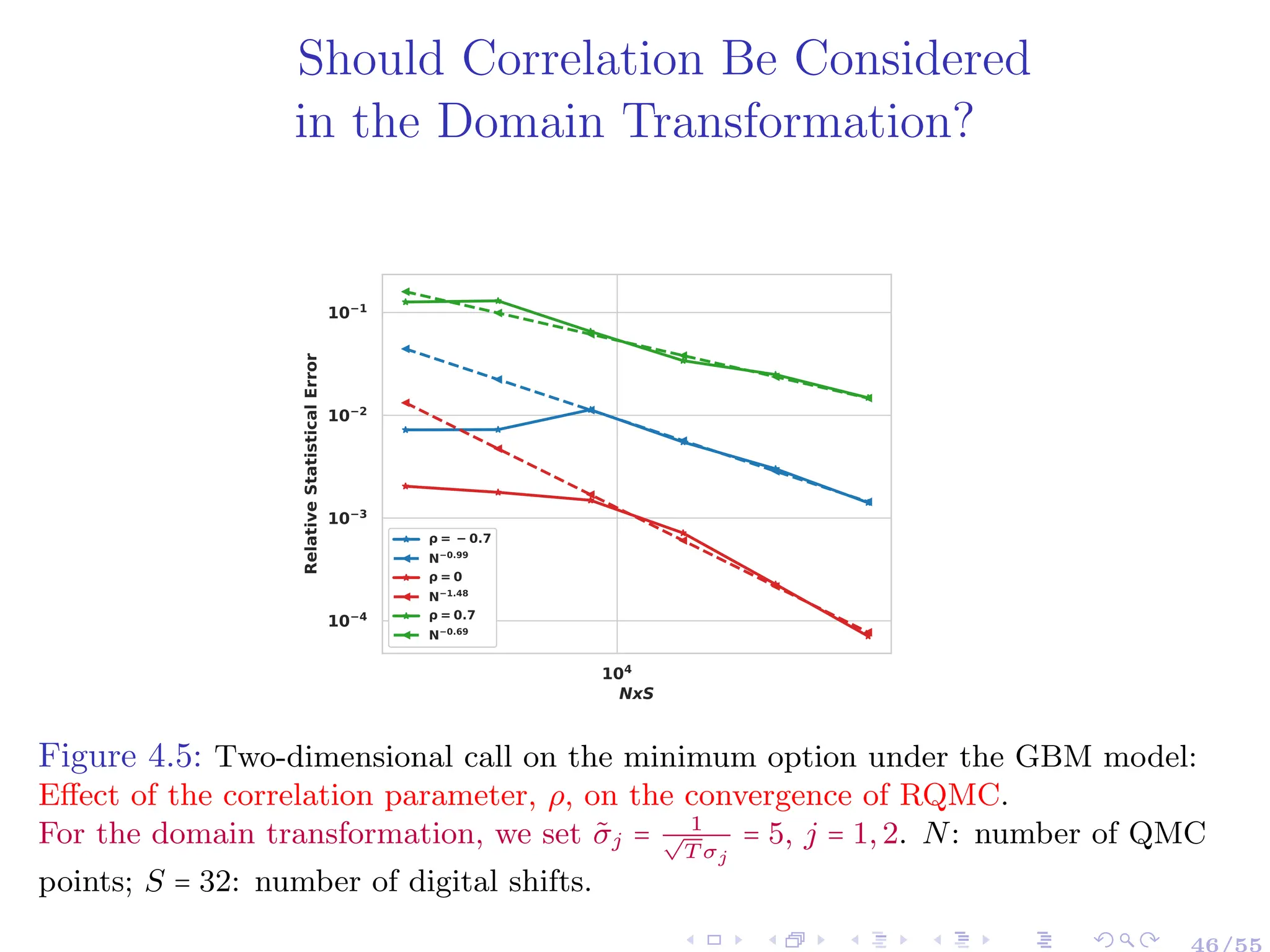

![Challenge 4: Deterioration of QMC convergence if ψ

or/and Λ are badly chosen

Observe: The denominator of g̃(u) =

g○Ψ−1(u;Λ)

ψ○Ψ−1(u;Λ)

decays to 0 as

uj → 0,1 for j = 1,...,d.

The transformed integrand may have singularities near the

boundary of [0,1]d

⇒ Deterioration of QMC convergence.

−20 −15 −10 −5 0 5 10 15 20

u

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

g

(

u

)

(a) Original Fourier integrand

for call option under GBM

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

u

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

̃

g

(

u

)

̃ ̃

σ = 1.0

̃ ̃

σ = 5.0

̃ ̃

σ = 9.0

(b) Transformed integrand, based

on Gaussian density with scale σ̃.

Questions

Q1: Which density to choose? Q2: How to choose its parameters?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-47-2048.jpg)

![Challenge 4: Deterioration of QMC convergence if ψ

or/and Λ are badly chosen

Observe: The denominator of g̃(u) =

g○Ψ−1(u;Λ)

ψ○Ψ−1(u;Λ)

decays to 0 as

uj → 0,1 for j = 1,...,d.

The transformed integrand may have singularities near the

boundary of [0,1]d

⇒ Deterioration of QMC convergence.

−20 −15 −10 −5 0 5 10 15 20

u

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

g

(

u

)

(a) Original Fourier integrand

for call option under GBM

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

u

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

̃

g

(

u

)

̃ ̃

σ = 1.0

̃ ̃

σ = 5.0

̃ ̃

σ = 9.0

(b) Transformed integrand, based

on Gaussian density with scale σ̃.

Questions

Q1: Which density to choose? Q2: How to choose its parameters?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-48-2048.jpg)

![How to choose ψ(⋅;Λ) (respectively Ψ−1(⋅;Λ) ) and

and its parameters, Λ?

For u ∈ [0,1]d

,R ∈ δV ⊂ Rd

, the transformed Fourier integrand reads:

g̃(u) =

g ○ Ψ−1

(u;Λ)

ψ ○ Ψ−1(u;Λ)

=

e−rT

(2π)d

R

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

̂

P(Ψ−1

(u) + iR)

ΦXT

(Ψ−1

(u) + iR)

ψ (Ψ−1(u))

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

.

⇒ Sufficient to design the domain transformation to control the growth

at the boundaries of the term

ΦXT

(Ψ−1(u)+iR)

ψ(Ψ−1(u))

(Conservative choice).

The payoff Fourier transforms ( ̂

P(⋅)) decay at a polynomial rate.

PDFs of the pricing models (light and semi-heavy tailed models), if

they exist, are much smoother than the payoff ⇒ the decay of their

Fourier transforms (charactersitic functions) is faster the one of the

payoff Fourier transform (Trefethen 1996; Cont et al. 2003).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-49-2048.jpg)

![How to choose ψ(⋅;Λ) (respectively Ψ−1(⋅;Λ) ) and

and its parameters, Λ?

For u ∈ [0,1]d

,R ∈ δV ⊂ Rd

, the transformed Fourier integrand reads:

g̃(u) =

g ○ Ψ−1

(u;Λ)

ψ ○ Ψ−1(u;Λ)

=

e−rT

(2π)d

R

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

̂

P(Ψ−1

(u) + iR)

ΦXT

(Ψ−1

(u) + iR)

ψ (Ψ−1(u))

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

.

⇒ Sufficient to design the domain transformation to control the growth

at the boundaries of the term

ΦXT

(Ψ−1(u)+iR)

ψ(Ψ−1(u))

(Conservative choice).

The payoff Fourier transforms ( ̂

P(⋅)) decay at a polynomial rate.

PDFs of the pricing models (light and semi-heavy tailed models), if

they exist, are much smoother than the payoff ⇒ the decay of their

Fourier transforms (charactersitic functions) is faster the one of the

payoff Fourier transform (Trefethen 1996; Cont et al. 2003).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-50-2048.jpg)

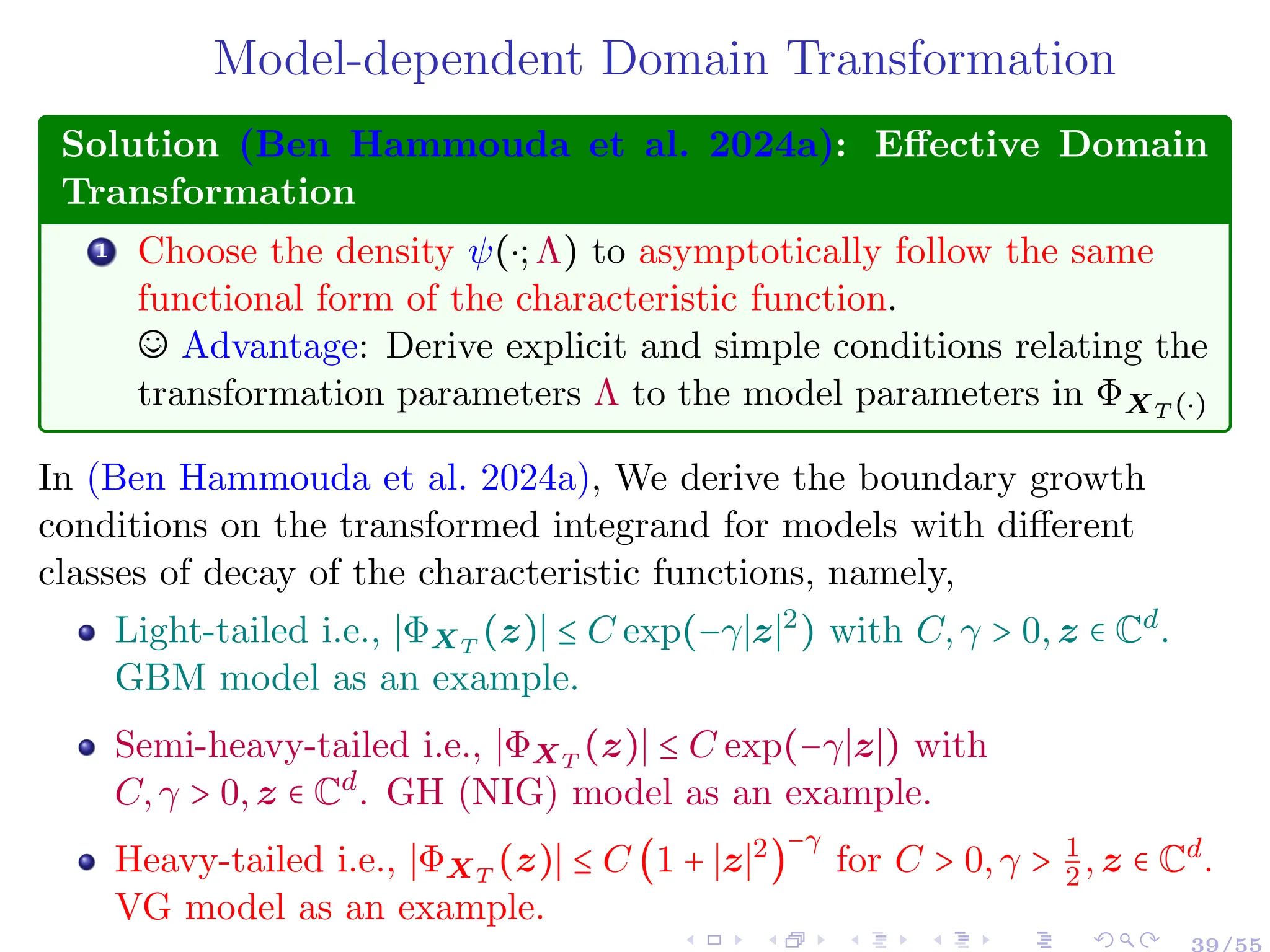

![Model-dependent Domain Transformation

Solution (Ben Hammouda et al. 2024a): Effective Domain Transformation

1 Choose the density ψ(⋅;Λ) to asymptotically follow the same functional form of the

characteristic function.

© Advantage: Derive explicit and simple conditions relating the transformation parameters Λ

to the model parameters in ΦXT (⋅)

Table 6: Extended characteristic function: ΦXT

(z) = exp(iz′

X0)exp(iz′

µT)ϕXT

(z), and choice of ψ(⋅).

ϕXT

(z),z ∈ Cd

, I[z] ∈ δX ψ(y;Λ),y ∈ Rd

Gaussian (Λ = Σ̃):

GBM model: exp(−T

2

z′

Σz)

(2π)− d

2 (det(Σ̃))− 1

2 exp(−1

2

(y′

Σ̃

−1

y))

Generalized Student’s t (Λ = (ν̃,Σ̃)):

VG model: (1 − iνz′

θ + 1

2

νz′

Σz)

−T /ν Γ( ν̃+d

2

)(det(Σ̃))− 1

2

Γ( ν̃

2

)ν̃

d

2 π

d

2

(1 + 1

ν̃

(y′

Σ̃y))

− ν̃+d

2

NIG model: Laplace (Λ = Σ̃) and (v = 2−d

2

):

exp(δT (

√

α2 − β′

∆β −

√

α2 − (β + iz)′∆(β + iz)))

(2π)− d

2 (det(Σ̃))− 1

2 (y′

Σ̃

−1

y

2

)

v

2

Kv (

√

2y′Σ̃

−1

y)

Notation:

Σ: Covariance matrix for the Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) model.

ν, θ, σ, Σ: Variance Gamma (VG) model parameters.

α, β, δ, ∆: Normal Inverse Gaussian (NIG) model parameters.

µ is the martingale correction term.

Kv(⋅): the modified Bessel function of the second kind.

40/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-52-2048.jpg)

![Model-dependent Domain Transformation:

Case of Independent Assets

Using independence: Observe

ϕXT

(Ψ−1

(u)+iR)

ψ(Ψ−1(u))

= ∏

d

j=1

ϕ

X

j

T

(Ψ−1

(uj )+iRj )

ψj (Ψ−1(uj ))

Solution (Ben Hammouda et al. 2024a): Effective Domain Transformation

1 Choose the density ψ(⋅;Λ) in the change of variable to asymptotically follow the same functional

form of the extended characteristic function.

2 Select the parameters Λ to control the growth of the integrand near the boundary of [0,1]d

i.e

limuj →0,1 g̃(uj) < ∞, j = 1,...,d.

Table 7: Choice of ψ(u;Λ) ∶= ∏

d

j=1 ψj(uj;Λ) and conditions on Λ for GBM, (ii) VG and (iii) NIG. See

(Ben Hammouda et al. 2024a) for the derivation.

Model ψj(yj;Λ) Growth condition on Λ

GBM

1

√

2σ̃j

2

exp(−

y2

j

2σ̃j

2 ) (Gaussian) σ̃j ≥ 1

√

T σj

VG

Γ( ν̃+1

2

)

√

ν̃πσ̃j Γ( ν̃

2

)

(1 +

y2

j

ν̃σ̃j

2 )

−(ν̃+1)/2

(t-Student) ν̃ ≤ 2T

ν

− 1,

σ̃j = (

νσ2

j ν̃

2

)

T

ν−2T

(ν̃)

ν

4T −2ν

NIG, GH

exp(−

∣yj ∣

σ̃j

)

2σ̃j

(Laplace) σ̃j ≥ 1

δT

" In case of equality conditions, the integrand still decays at the speed of the payoff transform.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-53-2048.jpg)

![Boundary Growth Conditions: GBM as Illustration

Consider the case of independent assets, s.t. the characteristic function can be

written as

ϕXT

(u) =

d

∏

j=1

ϕXj

T

(uj),u ∈ Rd

,

where

ϕXj

T

(uj) = exp(rT − i

σj

2

T

2

uj −

σj

2

T

2

u2

j )

For the domain transformation density, we propose ψ(u) = ∏

d

j=1 ψj(uj), with

ψj(uj) =

exp(−

u2

j

2σ̃2

j

)

√

2σ̃2

j

,uj ∈ R.

⇒ The transformed integrand can be written as (y ∈ [0,1]d

)

g̃(y) ∶= (2π)−d

e−rT

e−⟨R,X0⟩

R

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

ei⟨Ψ−1

(y),X0⟩ ̂

P (Ψ−1

(y) + iR)

d

∏

j=1

ϕXj

T

(Ψ−1

(yj) + iRj)

ψj(Ψ−1(yj))

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

.

42/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-54-2048.jpg)

![Boundary Growth Condition: GBM

The term controlling the growth of the integrand near the boundary is

rj(yj) ∶=

ϕXj

T

(Ψ−1

(yj) + iRj)

ψj(Ψ−1(yj))

, yj ∈ [0,1]. (9)

After some simplifications (9) reduces to

rj(yj) = σ̃j exp(−(Ψ−1

(yj))2

(

Tσ2

j

2

−

1

2σ̃2

j

))

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

∶=T1(controls the growth of the integrand near the boundary)

×

√

2π exp(−iTΨ−1

(yj)(

σ2

j

2

+ σ2

j Rj) + R2

j Tσ2

j + rT)

´¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¸¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¹¶

∶=T2 (bounded)

,

If we set σ̃j ≥ 1

√

T σj

⇒ T1 < ∞ as yj → 0,1 (since (Ψ−1

(yj))2

→ +∞).

43/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-55-2048.jpg)

![Evaluation of Ψ−1

Distribution of ΨY belongs to the class of (centered) normal

mean-variance mixtures i.e. Y

d

=

√

WL ⋅ Z, with Z ∼ N(0,Id)

independent of W, and L ∈ Rd×d

(a Cholesky factor).

Applying an affine transformation in the integration yields (see

(Ben Hammouda et al. 2024a) for the proofs):

∫

[0,1]d

g (Ψ−1

Y (u))

ψY (Ψ−1

Y (u))

du = ∫

[0,1]d+1

g (Ψ−1

√

W

(ud+1)LΨ−1

Z (u−(d+1)))

ψY (Ψ−1

√

W

(ud+1)LΨ−1

Z (u−(d+1)))

du, (10)

with u−(d+1) denotes the vector excluding the (d + 1)-th

component.

(10) can be computed using QMC with (d + 1)-dimensional LDPs.

For the multivariate t-student distribution:

√

W follows the

inverse chi distribution with degrees of freedom ν̃.

For the multivariate Laplace distribution:

√

W follows the

Rayleigh distribution with scale 1

√

2

.

48/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-61-2048.jpg)

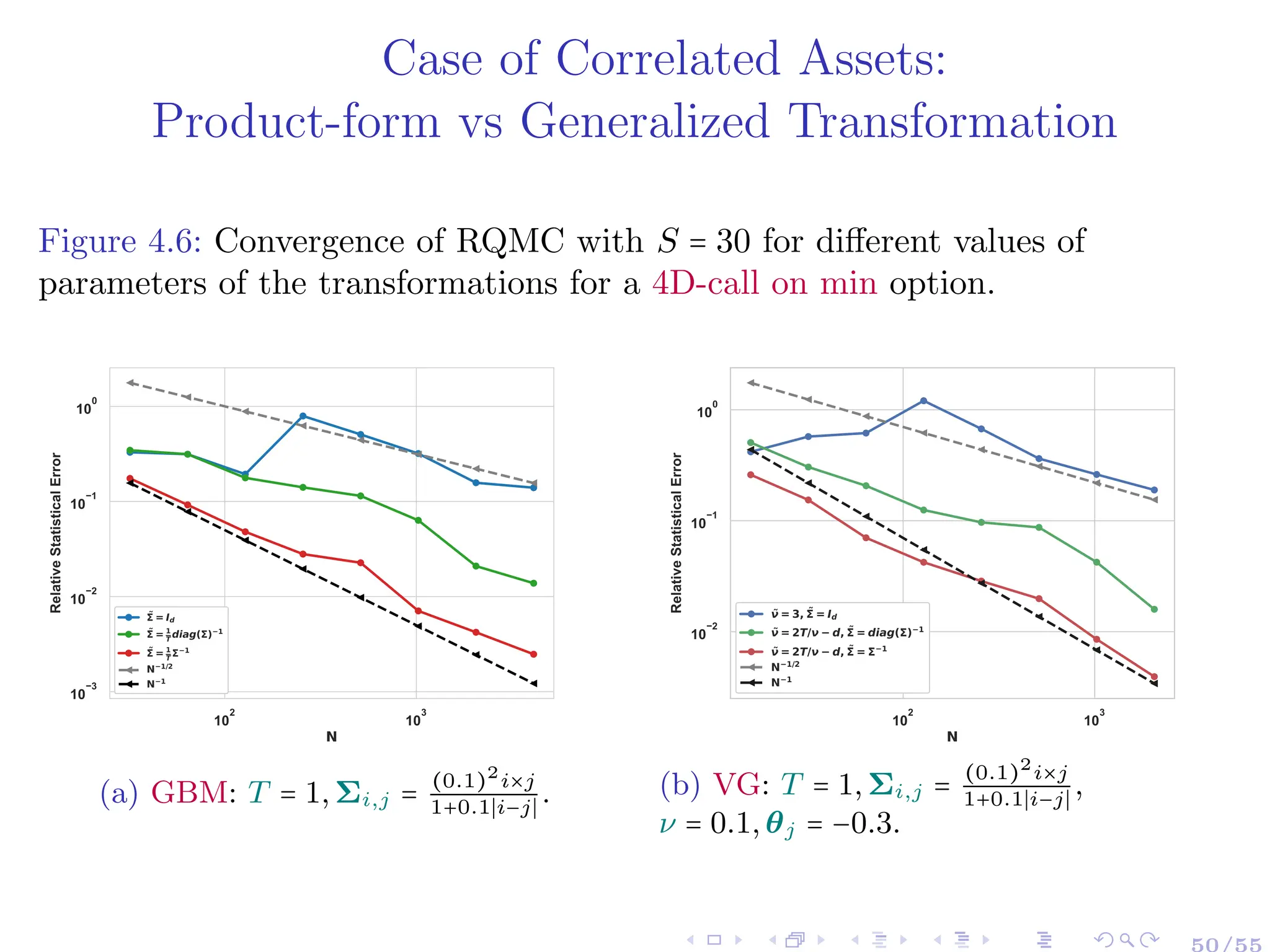

![Model-dependent Domain Transformation:

Case of Correlated Assets

Solution (Ben Hammouda et al. 2024a): Effective Domain Transformation

1 Choose the density ψ(⋅;Λ) in the change of variable to asymptotically follow the

same functional form of the extended characteristic function.

2 Select the parameters Λ to control the growth of the integrand near the boundary

of [0,1]d

i.e limuj→0,1 g̃(uj) < ∞,j = 1,...,d.

Table 8: Choice of ψ(u;Λ) ∶= ∏

d

j=1 ψj(uj;Λ) and sufficient conditions on Λ for GBM, (ii) VG and

(iii) NIG. See (Ben Hammouda et al. 2024a) for the derivation. Kλ(y) is the modified Bessel

function of the second kind with λ = 2−d

2

, y > 0. ” ⪰ 0” ∶ denotes positive-semidefiniteness of a

matrix

Model ψ(y;Λ) Growth condition on Λ

GBM Gaussian: (2π)− d

2 (det(Σ̃))− 1

2 exp(−1

2(y′

Σ̃

−1

y)) TΣ − Σ̃

−1

⪰ 0

VG Generalized Student’s t:

Γ(ν̃+d

2

)(det(Σ̃))− 1

2

Γ(ν̃

2

)ν̃

d

2 π

d

2

(1 + 1

ν̃

(y′

Σ̃y))

− ν̃+d

2

ν̃ = 2T

ν −d, Σ−Σ̃

−1

⪰ 0

or

ν̃ ≤ 2T

ν − d, Σ̃ = Σ−1

GH Laplace: (2π)− d

2 (det(Σ̃))− 1

2 (y′Σ̃

−1

y

2 )

λ

2

Kλ (

√

2y′Σ̃

−1

y) δ2

T2

∆ − 2Σ̃

−1

⪰ 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-62-2048.jpg)

![Conclusion

Task (Option Pricing and Beyond): Efficiently compute:

E[g(X(T))] = ∫

Rd

g(x) ρXT

(x) dx.

The pdf, ρXT

, is not known explicitly or expensive to

sample from.

g(⋅) is non-smooth.

The dimension d is large.

54/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-68-2048.jpg)

![Conclusion

Task (Option Pricing and Beyond): Efficiently compute:

E[g(X(T))] = ∫

Rd

g(x) ρXT

(x) dx.

1 Uncovering the Available Hidden Regularity:

Physical space:

∫Rd g(x) ρXT

(x) dx

Fourier space:

1

(2π)d ∫Rd ̂

g(u + iR) Φ(u + iR) du

Fourier Transform

2 Parametric Smoothing:

Challenge:

Arbitrary choices for R may deteriorate

the regularity of Fourier integrand.

Solution:

(Generic) optimization rule for the choice of R

based on contour integration error estimates.

3 Addressing the Curse of Dimension:

Challenge:

Complexity of (standard) tensor

product (TP) quadrature ↗

exponentially with the dimension, d.

Solution:

▸ Sparsification and dimension-adaptivity.

▸ Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) with efficient domain

transformation.

54/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-69-2048.jpg)

![References I

[1] J.-P. Aguilar. “Some pricing tools for the Variance Gamma

model”. In: International Journal of Theoretical and Applied

Finance 23.04 (2020), p. 2050025.

[2] C. Bayer, M. Siebenmorgen, and R. Tempone. “Smoothing the

payoff for efficient computation of basket option pricing.”. In:

Quantitative Finance 18.3 (2018), pp. 491–505.

[3] C. Ben Hammouda, C. Bayer, and R. Tempone. “Hierarchical

adaptive sparse grids and quasi-Monte Carlo for option pricing

under the rough Bergomi model”. In: Quantitative Finance 20.9

(2020), pp. 1457–1473.

[4] C. Ben Hammouda, C. Bayer, and R. Tempone. “Numerical

smoothing with hierarchical adaptive sparse grids and

quasi-Monte Carlo methods for efficient option pricing”. In:

Quantitative Finance (2022), pp. 1–19.

55/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-72-2048.jpg)

![References II

[5] C. Ben Hammouda et al. “Optimal Damping with Hierarchical

Adaptive Quadrature for Efficient Fourier Pricing of Multi-Asset

Options in Lévy Models”. In: Journal of Computational Finance

27.3 (2023), pp. 43–86.

[6] C. Ben Hammouda et al. “Quasi-Monte Carlo for Efficient

Fourier Pricing of Multi-Asset Options”. In: arXiv preprint

arXiv:2403.02832 (2024).

[7] C. Ben Hammouda, C. Bayer, and R. Tempone. “Multilevel

Monte Carlo with numerical smoothing for robust and efficient

computation of probabilities and densities”. In: SIAM Journal on

Scientific Computing 46.3 (2024), A1514–A1548.

[8] P. Carr and D. Madan. “Option valuation using the fast Fourier

transform”. In: Journal of computational finance 2.4 (1999),

pp. 61–73.

55/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-73-2048.jpg)

![References III

[9] P. Chen. “Sparse quadrature for high-dimensional integration

with Gaussian measure”. In: ESAIM: Mathematical Modelling

and Numerical Analysis 52.2 (2018), pp. 631–657.

[10] R. Cont and P. Tankov. Financial Modelling with Jump

Processes. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2003.

[11] P. J. Davis and P. Rabinowitz. Methods of numerical integration.

Courier Corporation, 2007.

[12] J. Dick, F. Y. Kuo, and I. H. Sloan. “High-dimensional

integration: the quasi-Monte Carlo way”. In: Acta Numerica 22

(2013), pp. 133–288.

[13] D. Duffie, D. Filipović, and W. Schachermayer. “Affine processes

and applications in finance”. In: The Annals of Applied

Probability 13.3 (2003), pp. 984–1053.

55/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-74-2048.jpg)

![References IV

[14] E. Eberlein. “Jump–type Lévy processes”. In: Handbook of

financial time series. Springer, 2009, pp. 439–455.

[15] E. Eberlein, K. Glau, and A. Papapantoleon. “Analysis of Fourier

transform valuation formulas and applications”. In: Applied

Mathematical Finance 17.3 (2010), pp. 211–240.

[16] O. El Euch, J. Gatheral, and M. Rosenbaum. “Roughening

heston”. In: Risk (2019), pp. 84–89.

[17] O. G. Ernst, B. Sprungk, and L. Tamellini. “Convergence of

sparse collocation for functions of countably many Gaussian

random variables (with application to elliptic PDEs)”. In: SIAM

Journal on Numerical Analysis 56.2 (2018), pp. 877–905.

[18] F. Fang and C. W. Oosterlee. “A novel pricing method for

European options based on Fourier-cosine series expansions”. In:

SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 31.2 (2009), pp. 826–848.

55/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-75-2048.jpg)

![References V

[19] Z. He, C. Weng, and X. Wang. “Efficient computation of option

prices and Greeks by quasi–Monte Carlo method with smoothing

and dimension reduction”. In: SIAM Journal on Scientific

Computing 39.2 (2017), B298–B322.

[20] J. Healy. “The Pricing of Vanilla Options with Cash Dividends

as a Classic Vanilla Basket Option Problem”. In: arXiv preprint

arXiv:2106.12971 (2021).

[21] T. R. Hurd and Z. Zhou. “A Fourier transform method for

spread option pricing”. In: SIAM Journal on Financial

Mathematics 1.1 (2010), pp. 142–157.

[22] F. Y. Kuo, C. Schwab, and I. H. Sloan. “Quasi-Monte Carlo

methods for high-dimensional integration: the standard (weighted

Hilbert space) setting and beyond”. In: The ANZIAM Journal

53.1 (2011), pp. 1–37.

55/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-76-2048.jpg)

![References VI

[23] F. Y. Kuo et al. “High dimensional integration of kinks and

jumps—smoothing by preintegration”. In: Journal of

Computational and Applied Mathematics 344 (2018), pp. 259–274.

[24] A. L. Lewis. “A simple option formula for general jump-diffusion

and other exponential Lévy processes”. In: Available at SSRN

282110 (2001).

[25] J. A. Nichols and F. Y. Kuo. “Fast CBC construction of

randomly shifted lattice rules achieving O (n- 1+ δ) convergence

for unbounded integrands over Rs in weighted spaces with POD

weights”. In: Journal of Complexity 30.4 (2014), pp. 444–468.

[26] D. Ouyang, X. Wang, and Z. He. “Quasi-Monte Carlo for

unbounded integrands with importance sampling”. In: arXiv

preprint arXiv:2310.00650 (2023).

55/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-77-2048.jpg)

![References VII

[27] L. N. Trefethen. “Finite difference and spectral methods for

ordinary and partial differential equations”. In: (1996).

55/55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22slidesbenhamouda-250123205348-1bb4dd63/75/Empowering-Fourier-based-Pricing-Methods-for-Efficient-Valuation-of-High-Dimensional-Derivatives-78-2048.jpg)