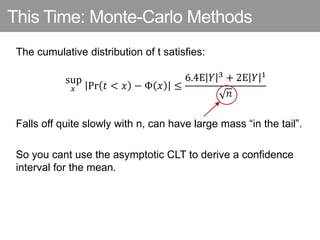

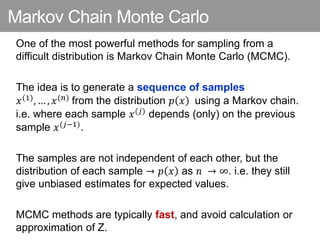

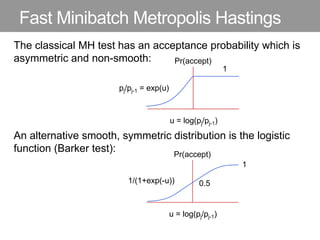

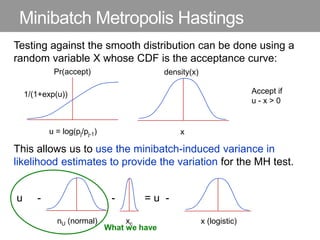

This document discusses Monte Carlo methods for approximating integrals and sampling from distributions. It introduces importance sampling to more efficiently sample from distributions, and Markov chain Monte Carlo methods like Gibbs sampling and Metropolis-Hastings algorithms to generate dependent samples that converge to the desired distribution. It also describes how minibatch Metropolis-Hastings allows efficient sampling of model parameters from minibatches of data using a smooth acceptance test.