This document summarizes information from various sources on several topics:

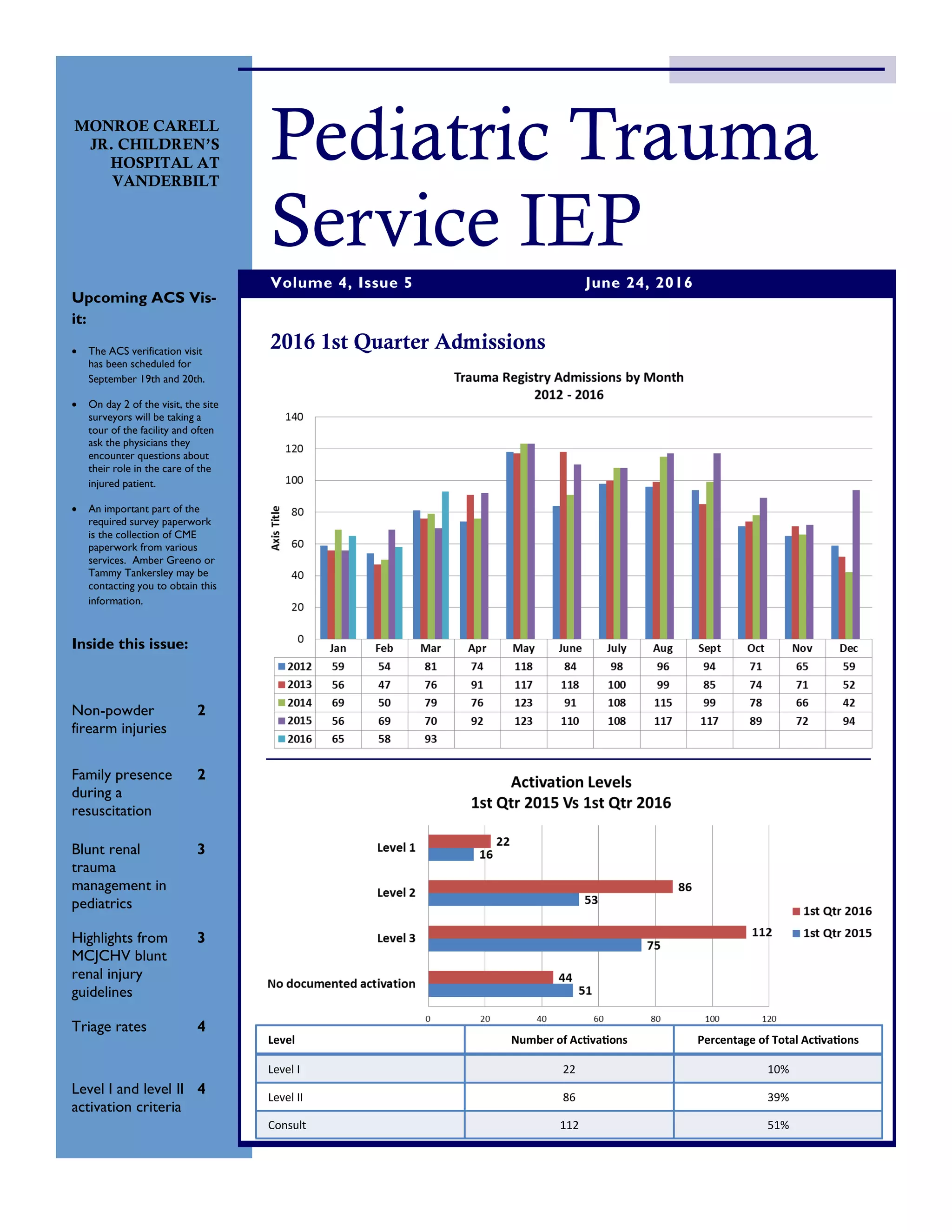

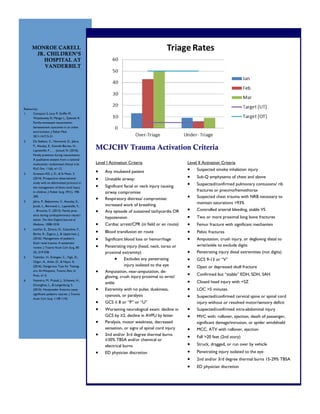

1) It provides guidelines from Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt for levels of trauma activation, including criteria for level I and level II activations.

2) It discusses the management of pediatric blunt renal trauma, highlighting guidelines that include recommendations for ICU stay, bed rest, imaging and antibiotics based on injury grade.

3) It summarizes literature on non-powder firearm injuries in pediatrics, noting they are underrecognized as dangerous and can cause injuries similar to handguns.