This document summarizes a study on the rheological properties of chemically modified rice starch model solutions. Native rice starches have poor resistance to shear and stability to retrogradation, which can be altered through chemical modifications like acetylation, cross-linking, and dual modification. The study investigated the effects of different combinations of modification reagents on the rheological properties of starches isolated from three rice cultivars. Results showed that acetylation and dual modification increased viscosity while cross-linking decreased viscosity. Modified starches also showed improved flow behavior and consistency compared to native starches. The effect of modification was similar across cultivars but varied most for the cultivar with relatively higher amylose content.

![starches (162 g, dry basis [db]) were placed in a 500-mL beaker and then

220 mL distilled water was added at 25C to obtain a 42.4% w/w (db) starch

suspension. The mixture was stirred using a magnetic stirrer until homoge-

neous slurry was obtained. The pH was adjusted to 8.0 by adding dropwise

3% aqueous sodium hydroxide solution. Then, the required amount of vinyl

acetate (4, 8 and 10%, on dry starch basis [dsb]) was added dropwise, while

simultaneously, 3% sodium hydroxide was also added to maintain the pH at

8.0–8.4 with continuous stirring. When the addition of vinyl acetate was

completed, the pH was adjusted to 4.5 with 0.5 N HCl to terminate the

reaction. The slurry was filtered under vacuum through a Buckner funnel. The

filtered cake was washed with 5 vol of distilled water. The resultant cake was

dried at 45C for about 8 h to bring moisture content to less than 12%. The

acetylated starch was ground, passed through a 75-mm sieve and stored in an

airtight container for further use.

Hydroxyethylation Cross-linking. The modification of starch was

carried out using the method of Wurzburg (1964) and Suwanliwong (1998) by

first reacting starch with EPH followed by adipic acid anhydride and vinyl

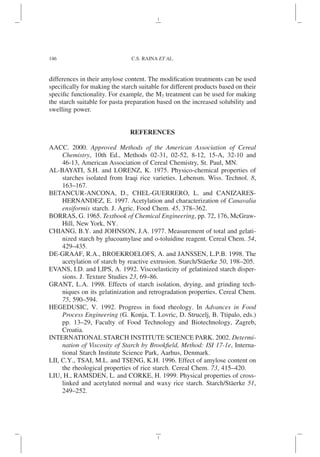

a

b

c

FIG. 1. SUGGESTED POSSIBLE STRUCTURE OF (a) ACETYLATED STARCH; (b)

HYDROXYETHYLATED STARCH; AND (c) ACETYLATED DISTARCH ADIPATE

137

RHEOLOGICAL PROPERTIES OF RICE STARCH MODEL SOLUTIONS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-210403205642/85/J-1745-4530-2006-00053-x-4-320.jpg)

![acetate. The etherification reaction was done at 40 ± 2C for 24 h using EPH in

a 40% w/w (db) starch slurry at pH 10.5 containing 15% sodium sulfate (db)

(to restrict starch swelling during modification) and 5% sodium hydroxide (to

maintain pH). Following etherification, the modified starch was cross-linked

for 2 h using adipic acid anhydride and vinyl acetate.

Sodium sulfate (30 g, 15% dsb) was added into water (300 mL) and

stirred. When the salt was dissolved, rice starch (200 g dsb, equivalent to 40%

starch solids in slurry) was added and the mixture was stirred to make a

uniform slurry. Then, 5% sodium hydroxide solution was added to slurry with

vigorous stirring to maintain the pH at 10.5. The EPH was added and the slurry

was stirred for 30 min at room temperature using a magnetic shaker. The slurry

was then transferred to glass bottles, contained in a shaking incubator at a

temperature of 40 ± 2C with shaking rate at 200 rpm and held for 24 h. The pH

(8.0–8.5) of the slurry was noted and maintained, and then cross-linking

reagent was added with vigorous shaking for 30 min. After that, the slurry was

again transferred to glass bottles and the reaction was allowed to proceed for

120 min at 40 ± 2C in an incubator shaker at 200 rpm. The starch slurry was

then adjusted to pH 5.5 with 10% HCl to terminate the reaction. The starch

was recovered under vacuum through the Buckner funnel. The filtered cake

was washed with 5 vol of distilled water. The resultant cake was dried at 45C

for about 8 h to bring moisture content to less than 12%. The modified starch

was ground, passed through a 75-mm sieve and stored in airtight containers for

further use.

Acetyl Content

The AG (%, db) and degree of substitution (DS) of rice starch were

determined according to Smith (1967). A 5-g sample of starch was weighed,

transferred to a 250-mL conical flask and dispersed in 50 mL of distilled water.

A few drops of phenolphthalein indicator were added and titrated with sodium

hydroxide 0.1 N to a permanent pink color. Then, 25.0 mL of 0.45 N NaOH

was added to it and was shaken vigorously for half an hour. The stopper and

neck of the flask was flushed with a little distilled water, and then the excess

alkali was titrated with 0.2 N HCl to the disappearance of the pink color.

Twenty-five milliliters of 0.45 N NaOH was titrated as a blank. AG and DS

were calculated as follows:

Acetyl group %

( ) =

−

( ) × ×

[ ]×

b s N

W

0 043 100

.

where b is the volume of 0.2 N HCl used to titrate the blank (mL); s is the

volume of 0.2 N HCl used to titrate the sample (mL); N is the normality of

0.2 N HCl; and W is the mass of the sample (g, db).

138 C.S. RAINA ET AL.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/j-210403205642/85/J-1745-4530-2006-00053-x-5-320.jpg)