This document provides a nutrition assessment and medical nutrition therapy plan for a 63-year-old male patient who underwent a laryngectomy, pharyngectomy, esophagectomy with gastric pull-up followed by radiation for squamous cell carcinoma. The registered dietitian found the patient to be at high nutritional risk due to a 23 pound unintended weight loss over the past year and being 79% of his ideal body weight at the time of surgery. The initial plan was to start enteral nutrition via tube feeding post-operatively. Follow-up notes document the patient tolerating the tube feeding well with some loose stools. The plan was adjusted to a fiber-containing formula and supplements to address this. The registered diet

![Megan McDermett

March 28, 2016

2

Labs

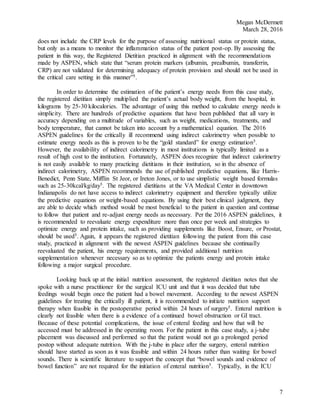

Albumin 3.0 L 11/05/2015

Anion Gap 4.0 11/13/2015

BUN 24 11/13/2015

Ca 8.1 11/13/2015

Cl 102 11/13/2015

CO2 30 11/13/2015

Creatinine 1.0 11/13/2015

Glucose 128 H 11/13/2015

K 3.9 11/13/2015

Na 136 11/13/2015

PO4 4.4 11/13/2015

eGFR 80.2 11/13/2015

SGOT 19 11/05/2015

SGPT 23 11/05/2015

Hgb A1c 4.9 05/07/2014

Mg 3.4 H 11/13/2015

Alk Phos 88 11/05/2015

Estimated Energy Requirements

Energy: 35-40 kcal/kg actual BW = 1700-1900 kcal/day

Protein: 1.5-2.0 gm/kg actual BW = 70-95 gm/day

Fluids: 1 ml/kcal = >1700 mls/day

Nutrition Diagnoses

1) Unintentional weight loss (NC-3.2 [Clinical category from the Academy of Nutrition and

Dietetics’ Nutrition Care Process terminology]) as related to odynophagia and dysphagia

secondary to squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx, cervical esophagus as

evidenced by a noted 23 pound weight loss over the last year.

2) Increased nutrient (protein and kcal) needs (NI-5.1 [Nutrient Intake category from the

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Nutrition Care Process terminology]) related to need

for healing post-op as evidenced by status post laryngophareygectomy, transhiatal

esophagectomy/j-tube placement with gastric pull-up.

Nutrition Intervention: Prescription/Plan

Initiate trickle feeds of Pivot 1.5 and advance to goal rate of 45 ml/hour continuous as patient

tolerates tube feeding. The goal rate of tube feeding provides 1620 kcals, 101 gm pro (2.1

gm/kg), and 820 mls free water. Additional free water autoflushes at 25 mls/hour will give the

patient 1420 mls of free water.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/23948b47-a3e5-4789-9455-909ab75c55cd-161212203137/85/ISPEN-MNT-Case-Study-2-320.jpg)

![Megan McDermett

March 28, 2016

3

Nutrition Intervention: MNT Goals

1) For the patient to tolerate the tube feeding so as to promote positive nutritional status

post-op and surgical wound healing.

2) For the patients electrolytes to be within normal limits status-post tube feeding initiation

so as to prevent refeeding syndrome.

3) For the patient to have normal bowel function post op so as to avoid post op ileus and

further decline in nutritional status.

Nutrition Monitoring/Evaluation

Dietitian will monitor patient’s weight, labs, electrolyte levels (magnesium, potassium, and

phosphorus), tube feeding tolerance, and overall hospital course. Patient’s nutritional status noted

as “severely compromised” and the patient will be reassessed within 3-5 days per hospital policy

unless a nutrition follow up is indicated anytime prior to 3-5 days.

Nutrition Status

This patient has been marked as “severely compromised” based on entire nutrition assessment.

Follow up Nutrition Assessment

Patient is a 63-year-old male status-post laryngopharyngectomy, transhiatal esophagectomy/j-

tube placement with gastric pull-up for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma with pharyngeal and

cervical esophageal extension. Patient communicating via “Boogie Board” eWriter. Patient

reports to be tolerating tube feeding well and denies any gastrointestinal discomfort. He reports

some loose stool, but otherwise all previous goals are being met. Noted that patient is also

receiving docusate, omeprazole, ondanseteron, and calcitriol.

Follow up Estimated Energy Requirements

Energy: 35-40 kcal/kg actual BW = 1700-1900 kcal/day

Protein: 1.5-2.0 gm/kg actual BW = 70-95 gm/day

Fluids: 1 ml/kcal = >1700 mls/day

(no change since initial assessment)

Follow up Nutrition Diagnoses

1) Unintentional weight loss (NC-3.2 [Clinical category from the Academy of Nutrition and

Dietetics’ Nutrition Care Process terminology]) as related to odynophagia and dysphagia

secondary to squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx, cervical esophagus as

evidenced by noted 23 pound weight loss over the last year.

2) Increased nutrient (protein and kcal) needs (NI-5.1 [Nutrient Intake category from the

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Nutrition Care Process terminology]) related to need

for healing post-op as evidenced by status post laryngophareygectomy, transhiatal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/23948b47-a3e5-4789-9455-909ab75c55cd-161212203137/85/ISPEN-MNT-Case-Study-3-320.jpg)