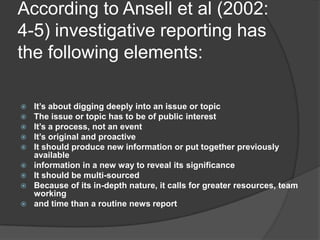

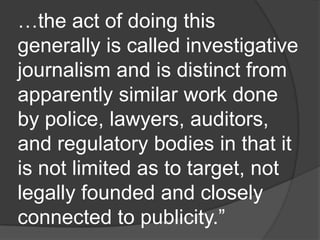

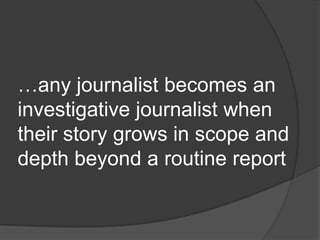

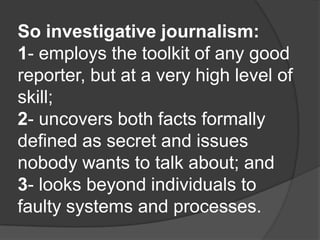

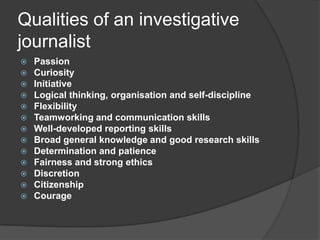

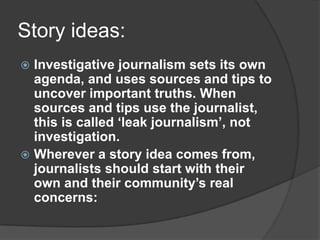

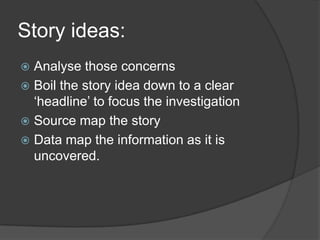

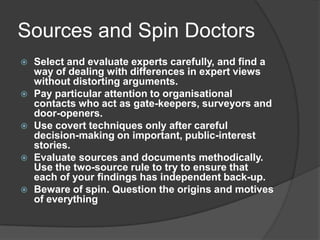

Investigative journalism involves deeply investigating topics of public interest, such as crime, corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. It requires original research through sources and documents to uncover new information or shed light on an issue in a way that reveals its significance. The core of investigative journalism is to uncover information that is in the public interest. Successful investigative journalists employ strong reporting skills, determination, and ethics to ferret out well-guarded information from hostile sources on issues that matter to readers.