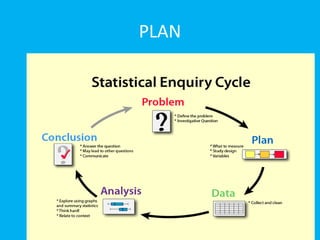

The document outlines investigation techniques by Richard Mayungbe, emphasizing the planning and methodological approach needed to conduct investigations into allegations of fraud, corruption, and ethical violations. It covers the definitions, scope, and purpose of investigations, the importance of avoiding conflicts of interest, and detailed components of an effective investigation plan. Additionally, it highlights the necessity of assessing investigatory powers and resources to ensure a successful inquiry.