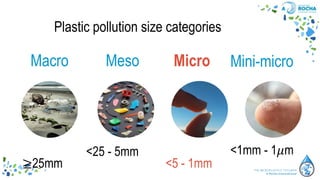

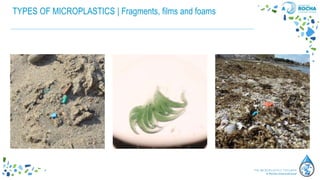

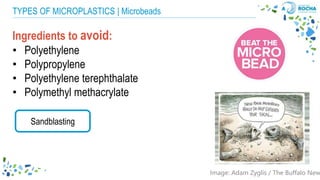

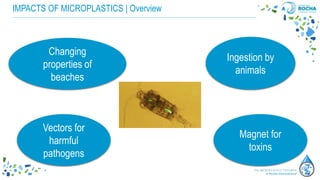

This document provides an introduction to microplastics, including their size categories and sources. It discusses the main types of microplastics such as fibers, pellets, fragments, films and foam. The impacts of microplastics are outlined, including ingestion by animals, changes to beach properties, spreading of pathogens, and concentration of toxins. Microplastics can be ingested by both marine life and humans.