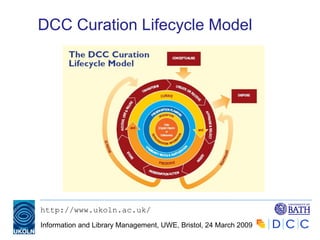

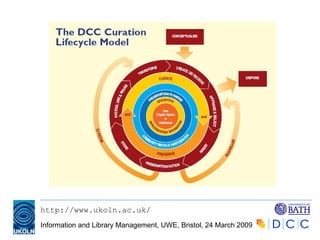

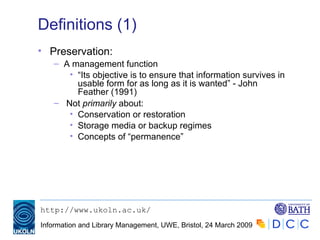

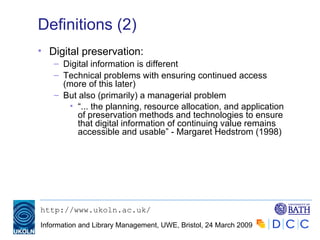

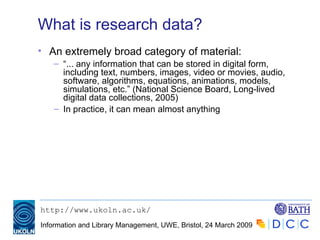

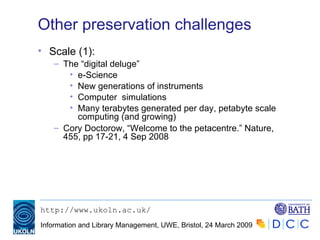

The document provides an overview of digital curation and preservation, emphasizing the importance of managing and preserving research data throughout its lifecycle. It discusses key concepts, definitions, roles, and responsibilities within the preservation process, while highlighting challenges and strategies for effective digital preservation. The document also explores the necessity of ensuring accessibility to valuable digital information and addresses the complexities involved in various preservation approaches.

![An introduction to digital curation and preservation Michael Day Digital Curation Centre UKOLN, University of Bath [email_address] Information and Library Management, University of the West of England, Bristol, 24 March 2009 Slides available on SlideShare: http://www.slideshare.net/michaelday](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/day-msc-2009-01-090323203249-phpapp01/75/Introduction-to-digital-curation-1-2048.jpg)

![Curation infrastructures (2) The need for collaboration: Need for 'deep-infrastructure' recognised as far back as 1996 by the Task Force on Archiving of Digital Information Digital preservation involves the "grander problem of organizing ourselves over time and as a society ... [to manoeuvre] effectively in a digital landscape" (p. 7)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/day-msc-2009-01-090323203249-phpapp01/85/Introduction-to-digital-curation-65-320.jpg)