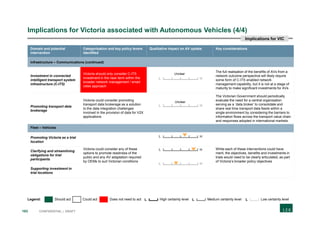

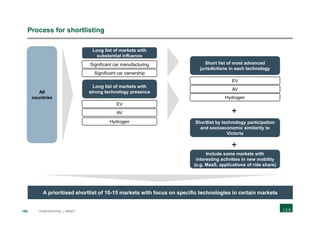

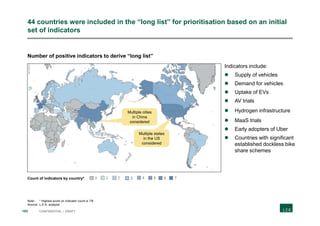

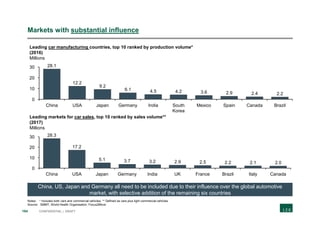

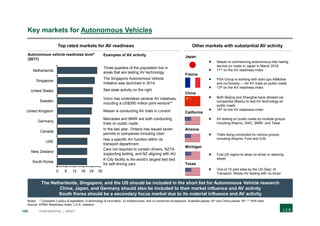

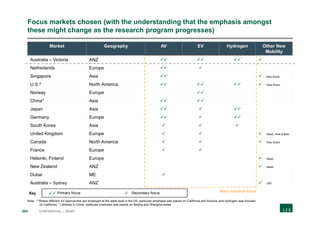

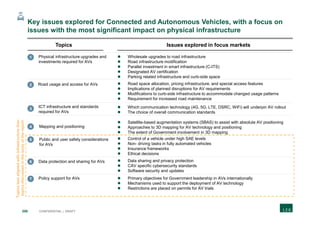

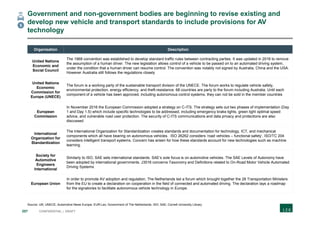

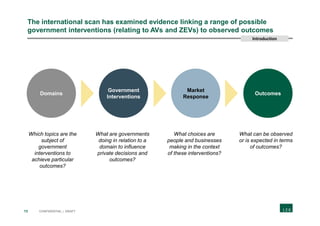

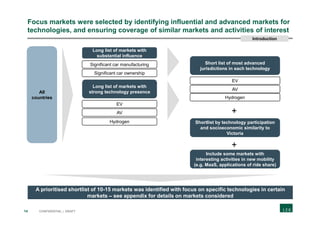

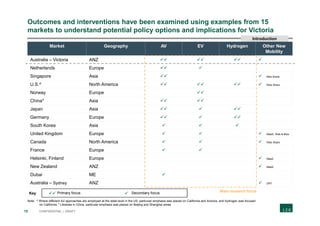

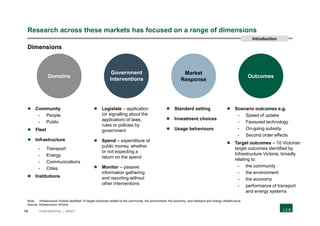

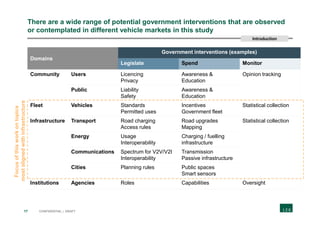

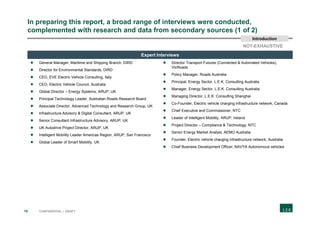

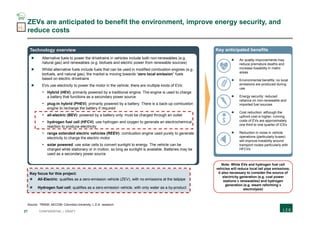

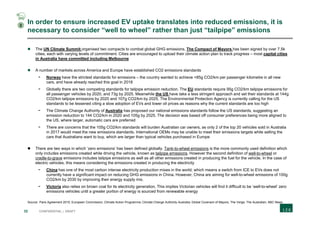

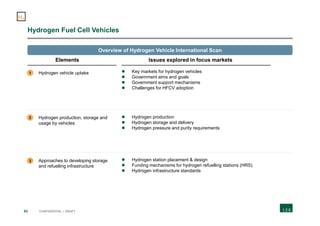

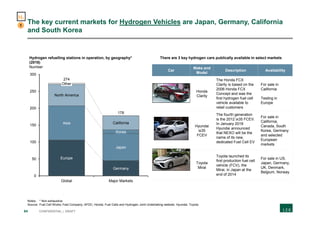

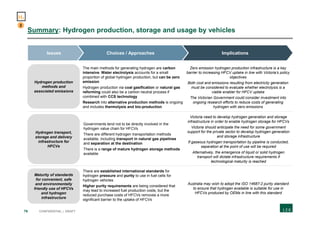

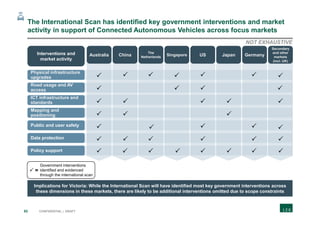

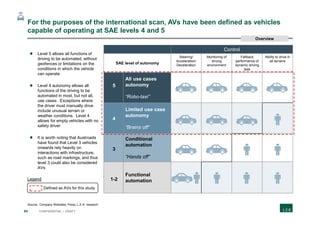

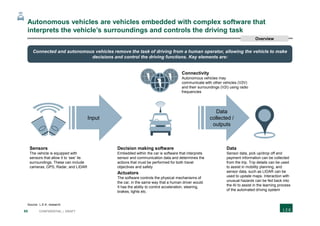

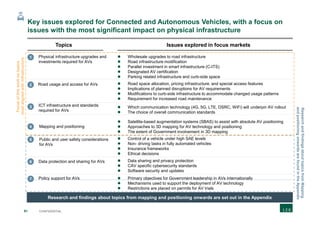

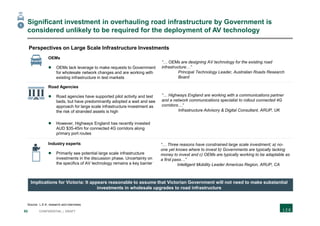

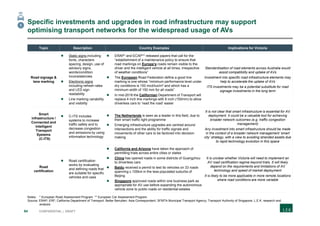

The document discusses a report by L.E.K. Consulting focused on the infrastructure requirements for implementing autonomous and zero emission vehicles in Victoria, Australia. It emphasizes the immaturity of these technologies while outlining potential government interventions to facilitate their adoption, such as promoting zero emissions electricity production and supporting hydrogen infrastructure. The report presents findings from an international scan of approximately 15 markets, identifying insights, implications, and possible strategies for the Victorian government to consider.

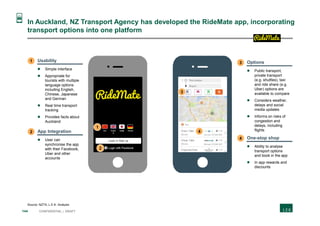

![143 CONFIDENTIAL | DRAFT

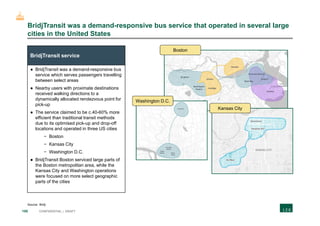

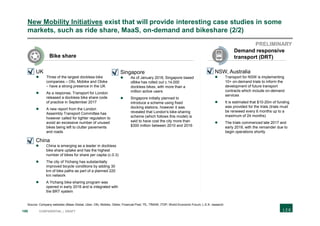

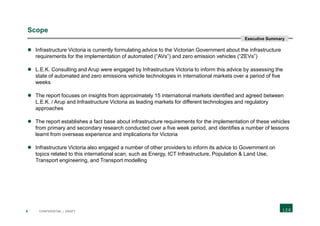

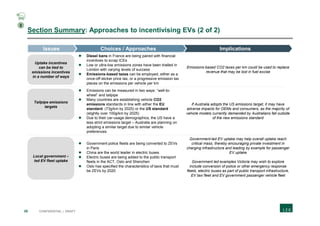

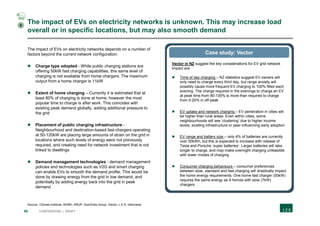

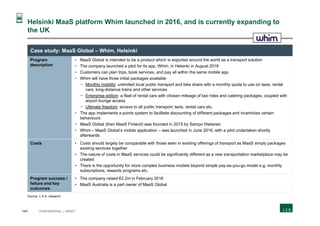

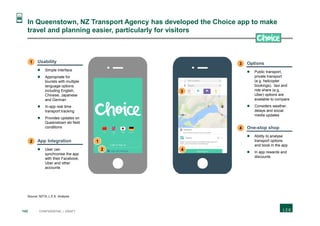

Choice has provided Queenstown tourists with the opportunity to access

personalised transport information and book their most efficient option

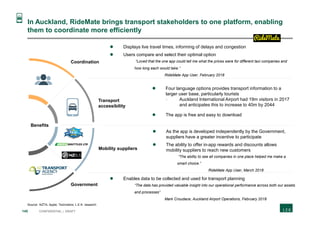

Coordination

Transport

accessibility

Mobility suppliers

Government

Assists visitors in accessing information and booking transport between

Queenstown airport, the city and ski areas

Facilitates the trip-planning process, providing a quicker, personalised journey for

customers

Information is simple, understandable and on one platform

Greater utilisation of existing government transport services

Increased tourism as travel locations (e.g. ski resorts) become more accessible

Benefits

The app improves accessibility to transport information for the 2m

tourists that visit annually

“Choice is available in three languages and will be a boost for the tourism

industry, reducing the language barriers for tourists using the local transport

system”

Simon Bridges, former NZ Transport Minister, August 2017

As the app is developed by the Government, suppliers have a greater

incentive to participate

“[The] obstacle of commercial rivalry was removed, and all transport providers

had an incentive to get on board”

Simon Bridges, former NZ Transport Minister, August 2017

Source: NZTA; L.E.K. Analysis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/infrastructurevictoriaavzevinternationalscan-180815121018/85/Infrastructure-Victoria-AZ-ZEV-International-Scan-143-320.jpg)