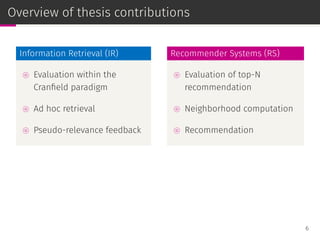

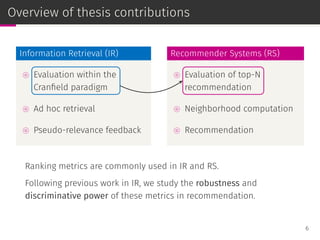

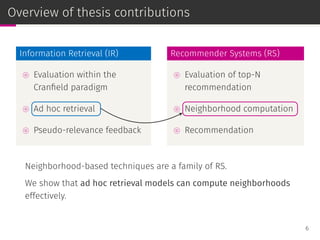

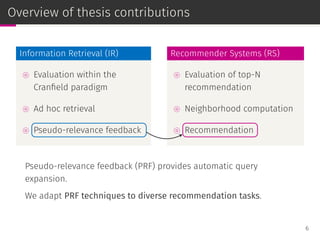

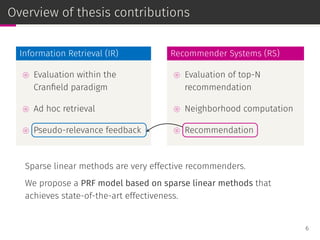

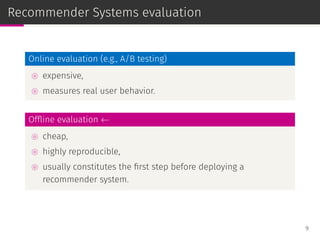

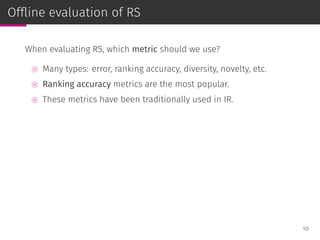

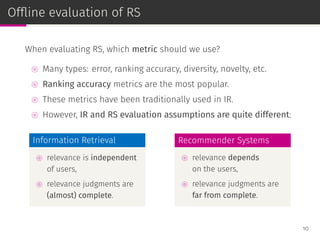

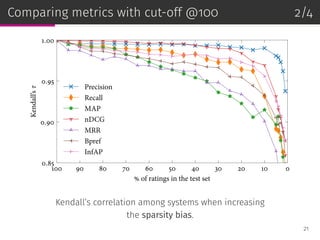

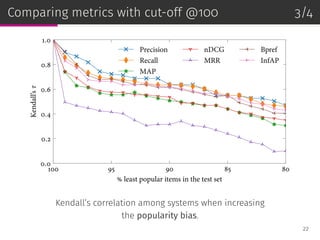

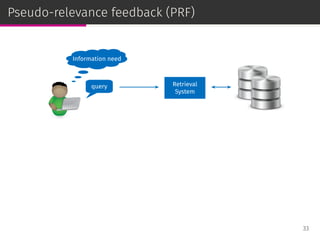

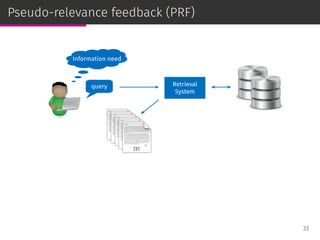

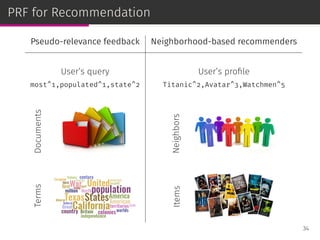

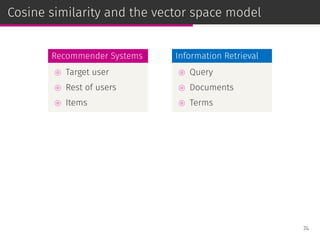

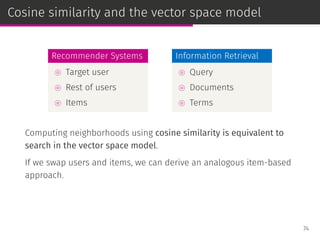

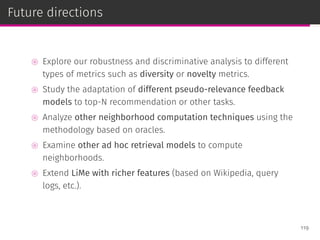

This PhD thesis by Daniel Valcarce explores the intersection of information retrieval models and recommender systems, emphasizing their shared goal of providing relevant information to users. The work includes evaluations of various recommendation techniques and metrics, highlighting robust methods for assessing the effectiveness of recommendations. Key contributions involve adapting information retrieval techniques for enhancing recommender systems, particularly through pseudo-relevance feedback and neighborhood-based approaches.

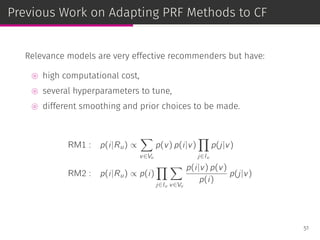

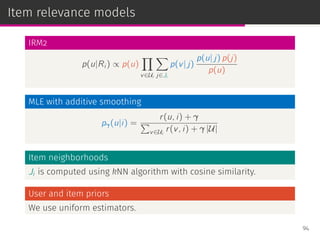

![Relevance models

Relevance-based language models or, simply, relevance models (RM)

are state-of-the-art PRF methods [Lavrenko & Croft, SIGIR ’01]:

⊚ RM1: i.i.d. sampling,

⊚ RM2: conditional sampling.

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-63-320.jpg)

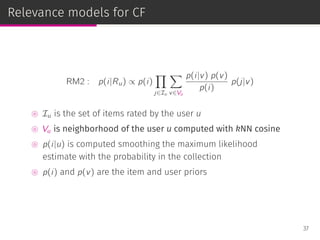

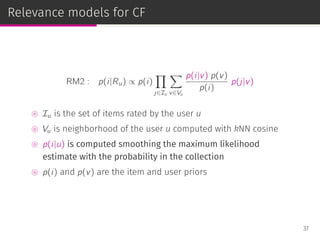

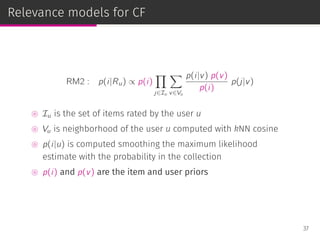

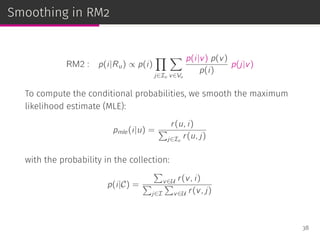

![Relevance models

Relevance-based language models or, simply, relevance models (RM)

are state-of-the-art PRF methods [Lavrenko & Croft, SIGIR ’01]:

⊚ RM1: i.i.d. sampling,

⊚ RM2: conditional sampling.

RM has been adapted to user-based CF [Parapar et al., IPM ’13].

36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-64-320.jpg)

![Why use smoothing?

In IR [Zhai & Lafferty, TOIS 2004], smoothing provides:

⊚ a way to deal with data sparsity,

⊚ inverse document frequency (IDF) effect,

⊚ document length normalization.

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-71-320.jpg)

![Why use smoothing?

In IR [Zhai & Lafferty, TOIS 2004], smoothing provides:

⊚ a way to deal with data sparsity,

⊚ inverse document frequency (IDF) effect,

⊚ document length normalization.

In RS, we have the same problems:

⊚ data sparsity,

⊚ item popularity/specificity,

⊚ user profiles with different sizes.

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-72-320.jpg)

![Smoothing techniques

Jelinek-Mercer smoothing (JMS): linear interpolation controlled by λ.

pλ(i|u) = (1 − λ) pmle(i|u) + λ p(i|C)

Dirichlet priors smoothing (DPS): Bayesian analysis with parameter µ.

pµ(i|u) =

r(u, i) + µ p(i|C)

µ +

∑

j∈Iu

r(u, j)

Absolute discounting smoothing (ADS): subtract a constant δ.

pδ(i|u) =

max[r(u, i) − δ, 0] + δ |Iu|p(i|C)

∑

j∈Iu

r(u, j)

Additive smoothing (AS): increase all the ratings by γ > 0.

pγ(i|u) =

r(u, i) + γ

∑

j∈Iu

r(u, j) + γ |I|

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-73-320.jpg)

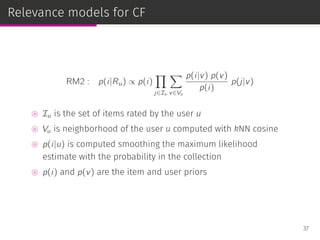

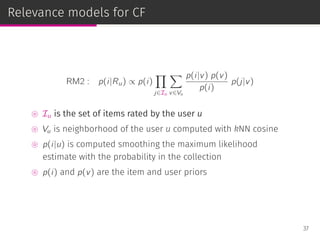

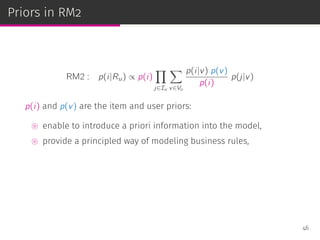

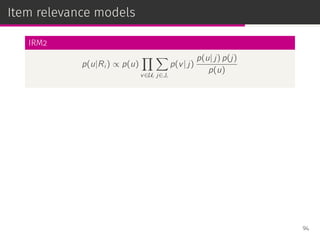

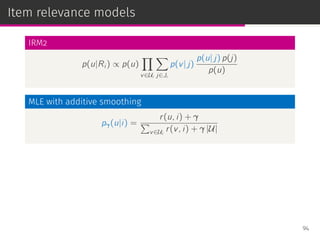

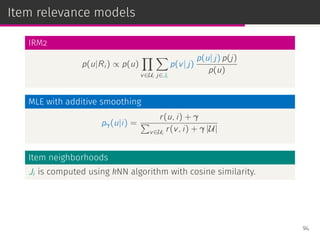

![Priors in RM2

RM2 : p(i|Ru) ∝ p(i)

∏

j∈Iu

∑

v∈Vu

p(i|v) p(v)

p(i)

p(j|v)

p(i) and p(v) are the item and user priors:

⊚ enable to introduce a priori information into the model,

⊚ provide a principled way of modeling business rules,

⊚ similar to document priors used in IR such as:

◦ linear document length prior [Kraaij et al., SIGIR ’02],

◦ probabilistic document length prior [Blanco & Barreiro, ECIR ’08].

46](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-83-320.jpg)

![Popular approaches to pseudo-relevance feedback

⊚ Relevance models

[Lavrenko & Croft, SIGIR ’01]

⊚ Scoring functions based on the Rocchio framework

[Rocchio, 1971; Carpineto et al., ACM TOIS ’01]

⊚ Divergence minimization model

[Zhai & Lafferty, SIGIR ’06]

⊚ Mixture models

[Tao & Zhai, SIGIR ’06]

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-89-320.jpg)

![Popular approaches to pseudo-relevance feedback

⊚ Relevance models

[Lavrenko & Croft, SIGIR ’01]

⊚ Scoring functions based on the Rocchio framework

[Rocchio, 1971; Carpineto et al., ACM TOIS ’01]

⊚ Divergence minimization model

[Zhai & Lafferty, SIGIR ’06]

⊚ Mixture models

[Tao & Zhai, SIGIR ’06]

52](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-90-320.jpg)

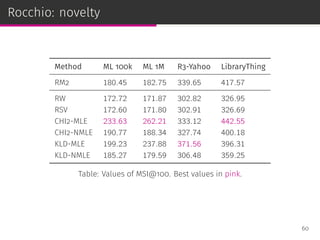

![Scoring functions from Rocchio framework

Rocchio Weights (RW)

pRW (i|u) =

∑

v∈Vu

r(v, i)

|Vu|

Robertson Selection Value (RSV)

pRSV (i|u) = p(i|Vu)

∑

v∈Vu

r(v, i)

|Vu|

CHI2

pCHI2 (i|u) =

[

p(i|Vu) − p(i|C)

]2

p(i|C)

Kullback–Leibler Divergence (KLD)

pKLD(i|u) = p(i|Vu) log

p(i|Vu)

p(i|C)

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-91-320.jpg)

![Scoring functions from Rocchio framework

Rocchio Weights (RW)

pRW (i|u) =

∑

v∈Vu

r(v, i)

|Vu|

Robertson Selection Value (RSV)

pRSV (i|u) = p(i|Vu)

∑

v∈Vu

r(v, i)

|Vu|

CHI2

pCHI2 (i|u) =

[

p(i|Vu) − p(i|C)

]2

p(i|C)

Kullback–Leibler Divergence (KLD)

pKLD(i|u) = p(i|Vu) log

p(i|Vu)

p(i|C)

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-92-320.jpg)

![Scoring functions from Rocchio framework

Rocchio Weights (RW)

pRW (i|u) =

∑

v∈Vu

r(v, i)

|Vu|

Robertson Selection Value (RSV)

pRSV (i|u) = p(i|Vu)

∑

v∈Vu

r(v, i)

|Vu|

CHI2

pCHI2 (i|u) =

[

p(i|Vu) − p(i|C)

]2

p(i|C)

Kullback–Leibler Divergence (KLD)

pKLD(i|u) = p(i|Vu) log

p(i|Vu)

p(i|C)

53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-93-320.jpg)

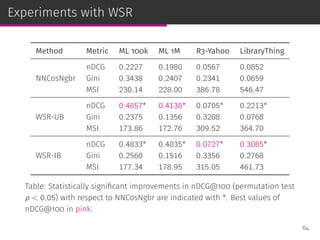

![Weighted sum recommender (WSR)

NNCosNgbr [Cremonesi et al., RecSys ’10]

We bias the MLE to perform neighborhood size normalization:

ˆru,i = bu,i +

∑

j∈Ji

shrunk_cosine (i, j) (r(u, j)−bu,i )

63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-104-320.jpg)

![Weighted sum recommender (WSR)

NNCosNgbr [Cremonesi et al., RecSys ’10]

We bias the MLE to perform neighborhood size normalization:

ˆru,i = bu,i +

∑

j∈Ji

shrunk_cosine (i, j) (r(u, j)−bu,i )

Item-based weighted sum recommender (WSR-IB)

ˆru,i =

∑

j∈Ji

cos (i, j) r(u, j)

User-based weighted sum recommender (WSR-UB)

ˆru,i =

∑

v∈Vu

cos (u, v) r(v, i)

63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-105-320.jpg)

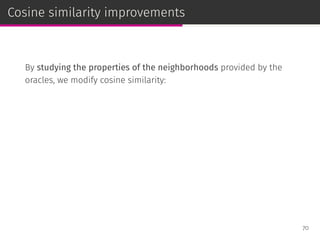

![Cosine similarity improvements

By studying the properties of the neighborhoods provided by the

oracles, we modify cosine similarity:

⊚ We penalize the cosine similarity to add user profile size

normalization.

◦ Similar to the pivoted document length normalization in IR

[Singhal et al., SIGIR ’96].

70](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-115-320.jpg)

![Cosine similarity improvements

By studying the properties of the neighborhoods provided by the

oracles, we modify cosine similarity:

⊚ We penalize the cosine similarity to add user profile size

normalization.

◦ Similar to the pivoted document length normalization in IR

[Singhal et al., SIGIR ’96].

⊚ We add the IDF effect to cosine similarity to increase the user

profile overlap of the neighbors.

◦ The IDF is a fundamental term specificity measure in IR.

70](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-116-320.jpg)

![Language models

Statistical language models are a state-of-the-art ad hoc retrieval

framework [Ponte & Croft, SIGIR ’98].

Documents are ranked according to their posterior probability given

the query:

p(d|q) =

p(q|d) p(d)

p(q)

rank

= p(q|d) p(d)

75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-124-320.jpg)

![Language models

Statistical language models are a state-of-the-art ad hoc retrieval

framework [Ponte & Croft, SIGIR ’98].

Documents are ranked according to their posterior probability given

the query:

p(d|q) =

p(q|d) p(d)

p(q)

rank

= p(q|d) p(d)

The query likelihood, p(q|d), is based on a unigram model:

p(q|d) =

∏

t∈q

p(t|d)c(t,d)

75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-125-320.jpg)

![Language models

Statistical language models are a state-of-the-art ad hoc retrieval

framework [Ponte & Croft, SIGIR ’98].

Documents are ranked according to their posterior probability given

the query:

p(d|q) =

p(q|d) p(d)

p(q)

rank

= p(q|d) p(d)

The query likelihood, p(q|d), is based on a unigram model:

p(q|d) =

∏

t∈q

p(t|d)c(t,d)

The document prior, p(d), is usually considered uniform.

75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-126-320.jpg)

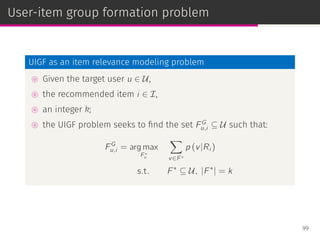

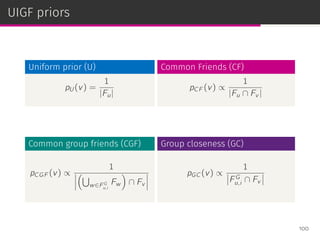

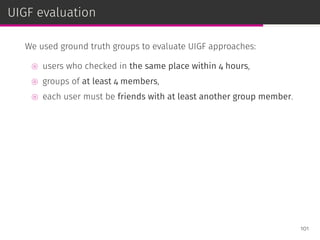

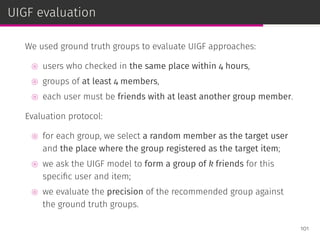

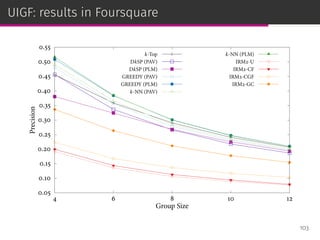

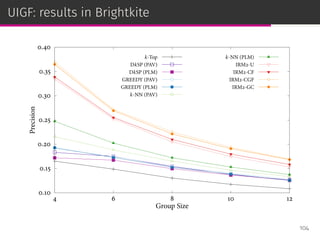

![User-item group formation

The user-item group formation (UIGF) problem aims to find the best

companions for a given item and a target user [Brilhante et al.,

ICMDM ’16].

98](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-156-320.jpg)

![User-item group formation

The user-item group formation (UIGF) problem aims to find the best

companions for a given item and a target user [Brilhante et al.,

ICMDM ’16].

IRM2:

⊚ estimates the relevance of a user given an item;

⊚ deals with long tail item liquidation with uniform priors.

98](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-157-320.jpg)

![User-item group formation

The user-item group formation (UIGF) problem aims to find the best

companions for a given item and a target user [Brilhante et al.,

ICMDM ’16].

IRM2:

⊚ estimates the relevance of a user given an item;

⊚ deals with long tail item liquidation with uniform priors.

We can model the user relationships with different priors estimators.

98](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-158-320.jpg)

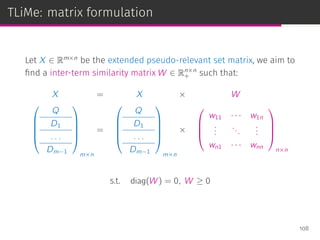

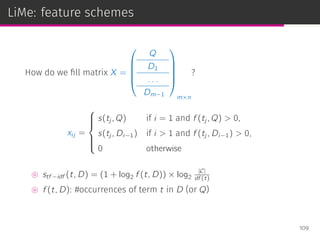

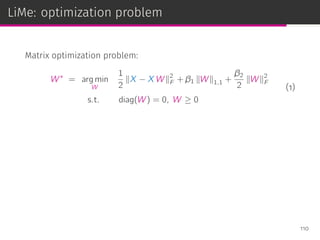

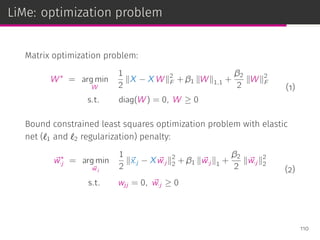

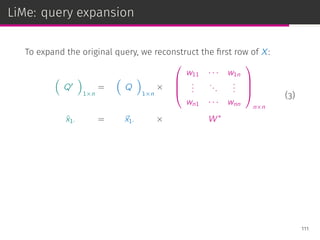

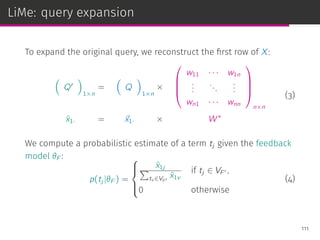

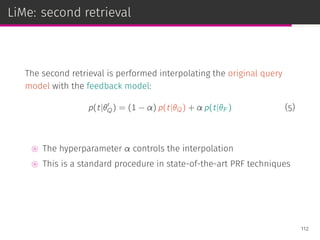

![LiMe: Linear Methods for PRF

Linear methods such as SLIM have been successfully used in

recommendation [Ning & Karypis, ICDM ’11].

We adapt them to PRF. Our proposal LiMe:

⊚ models the PRF task a matrix decomposition problem

⊚ employs linear methods to provide a solution

⊚ is able to learn inter-term or inter-doc similarities

⊚ jointly models the query and the pseudo-relevant set

⊚ admits different feature schemes

⊚ is agnostic to the retrieval model

106](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-167-320.jpg)

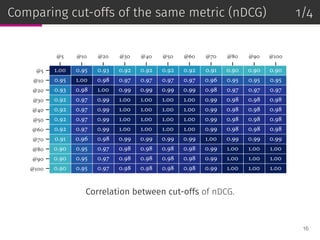

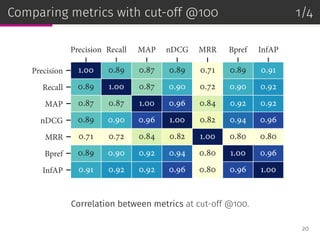

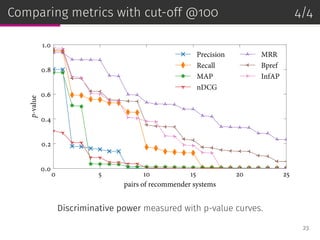

![Conferences (I)

gitemizeitemize4 [gitemize,1] leftmargin=0.3cm+, label=

A. Landin, D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “PRIN: A Probabilistic

Recommender with Item Priors and Neural Models”. ECIR ’19, pp.

133-147, 2019.

D. Valcarce, A. Bellogín, J. Parapar, P. Castells. “On the Robustness and

Discriminative Power of IR Metrics for Top-N Recommendation”.

ACM RecSys ’18, pp. 260-268, 2018.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “LiMe: Linear Methods for

Pseudo-Relevance Feedback”. ACM SAC ’18, pp. 678-687, 2018.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “Combining Top-N Recommenders

with Metasearch Algorithms”. ACM SIGIR ’17, pp. 805-808, 2017.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “Additive Smoothing for

Relevance-Based Language Modelling of Recommender Systems”. 121](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-193-320.jpg)

![Conferences (II)

gitemizeitemize4 [gitemize,1] leftmargin=0.3cm+, label=

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “Efficient Pseudo-Relevance

Feedback Methods for Collaborative Filtering Recommendation”.

ECIR ’16, pp. 602-613, 2016.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “Language Models for Collaborative

Filtering Neighbourhoods”. ECIR ’16, pp. 614-625, 2016.

D. Valcarce. “Exploring Statistical Language Models for Recommender

Systems”. ACM RecSys ’15, pp. 375-378, 2015.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “A Study of Priors for

Relevance-Based Language Modelling of Recommender Systems”.

ACM RecSys ’15, pp. 237-240, 2015.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “A Study of Smoothing Methods for

Relevance-Based Language Modelling of Recommender Systems”. 122](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-194-320.jpg)

![Journals

gitemizeitemize4 [gitemize,1] leftmargin=0.3cm+, label=

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “Document-based and Term-based Linear Methods

for Pseudo-Relevance Feedback”. Applied Computing Review 18(4), pp. 5-17, 2018.

D. Valcarce, I. Brilhante, J.A. Macedo, F.M. Nardini, R. Perego, C. Renso. “Item-driven

group formation”. Online Social Networks and Media 8, pp. 17-31, 2018.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “Finding and Analysing Good Neighbourhoods to

Improve Collaborative Filtering”. Knowledge-Based Systems 159, pp. 193-202, 2018.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “A MapReduce implementation of posterior

probability clustering and relevance models for recommendation”. Engineering

Applications of Artificial Intelligence 75, pp. 114-124, 2018.

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “Axiomatic Analysis of Language Modelling of

Recommender Systems”. International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and

Knowledge-Based Systems 25(2), pp. 113-128, 2017.

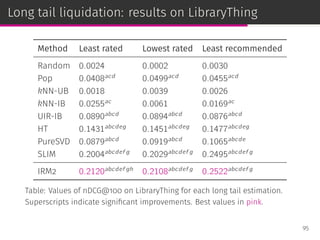

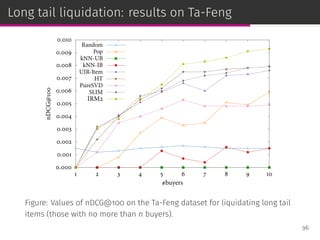

D. Valcarce, J. Parapar, Á. Barreiro. “Item-Based Relevance Modelling of

Recommendations for Getting Rid of Long Tail Products”. Knowledge-Based Systems

103, pp. 41-51, 2016. 123](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-190509153630/85/Information-Retrieval-Models-for-Recommender-Systems-PhD-slides-195-320.jpg)