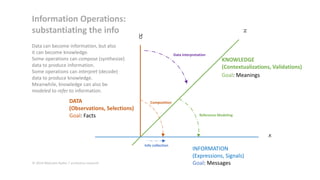

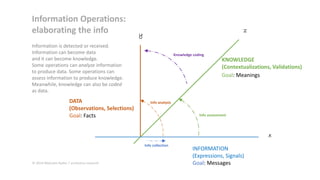

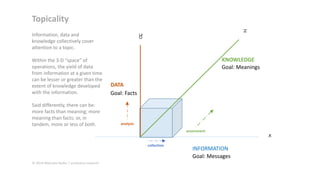

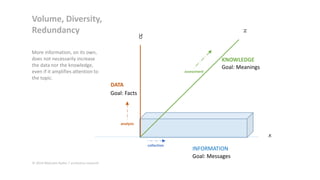

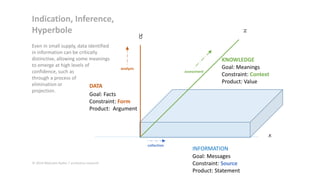

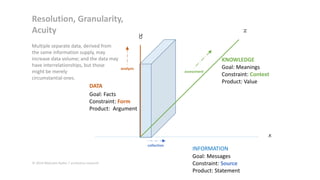

The document explores the relationship between data, information, and knowledge, arguing that they interact non-linearly and are defined by utilitarian needs and contextual use. It highlights the roles these elements play in communication and understanding, emphasizing that information processing involves various operations that can transform one into the other. Ultimately, the document presents content management as a crucial function in organizing and conceptualizing diverse intellectual materials within a given field of interest.