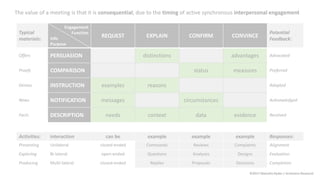

The document discusses the significance of meetings in the context of constant information access, emphasizing that they should only be held if they contribute to outcomes that cannot be achieved otherwise. Key factors for successful meetings include timing, the knowledge of attendees, and the actual accomplishments of the meeting. The Archestra research framework is presented as a tool for understanding the elements that drive effective meetings and the interactions within them.