The document discusses the composition and properties of mine air. It provides the following key points:

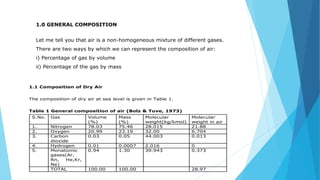

1. The main components of dry air are nitrogen (78.03%), oxygen (20.99%), and trace amounts of other gases like carbon dioxide and argon. The composition by mass is fixed but can vary by volume depending on humidity.

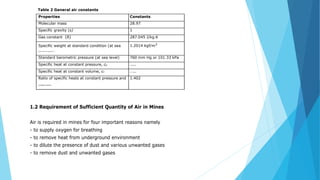

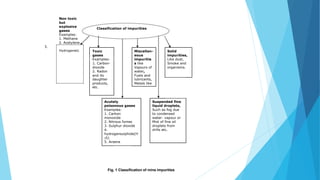

2. Air is required in mines to supply oxygen, remove heat, dilute dust and gases, and remove impurities. Mine air picks up impurities like carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapor.

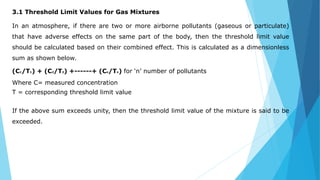

3. Threshold limit values (TLVs) define the maximum concentration of gases workers can be exposed to without health effects and are based on industrial experience and studies.