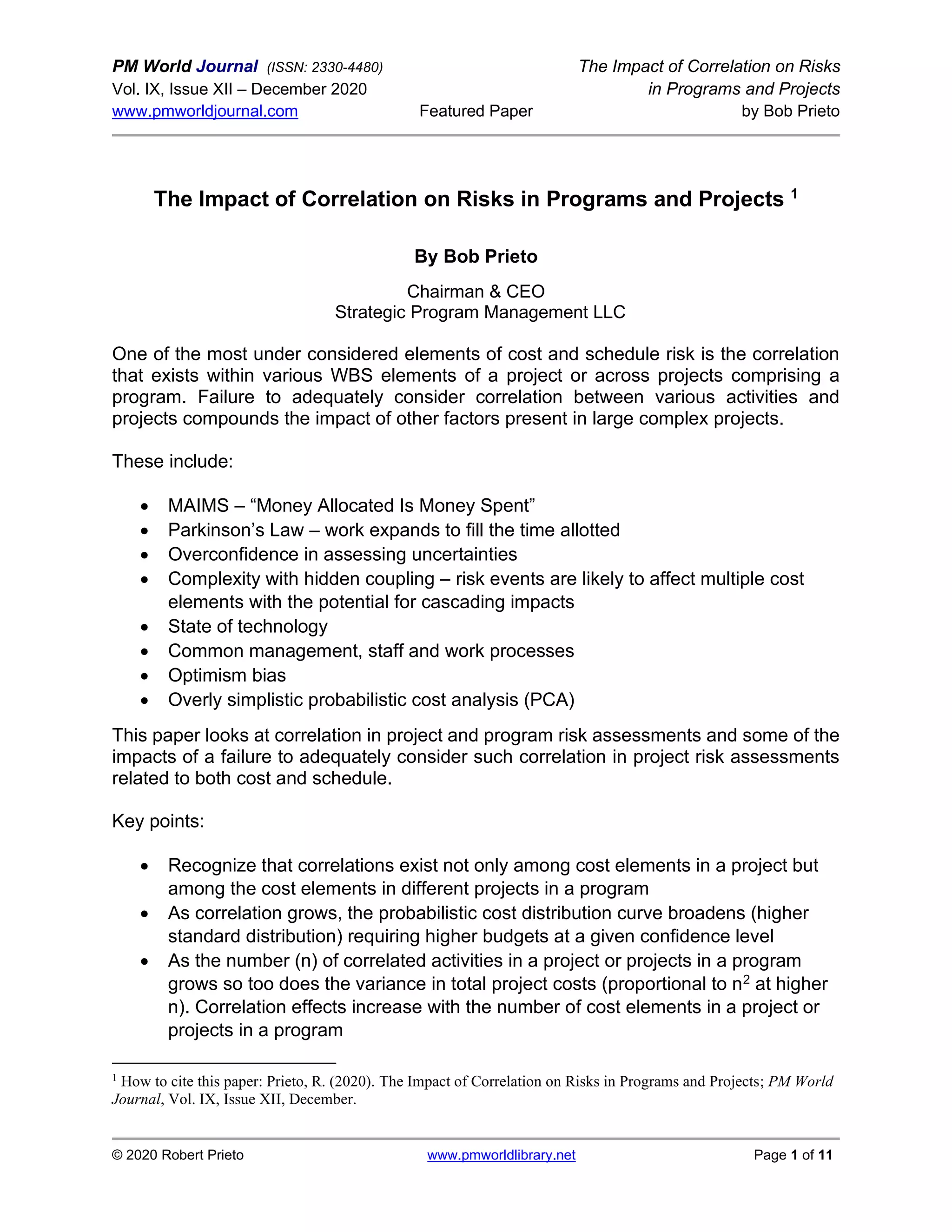

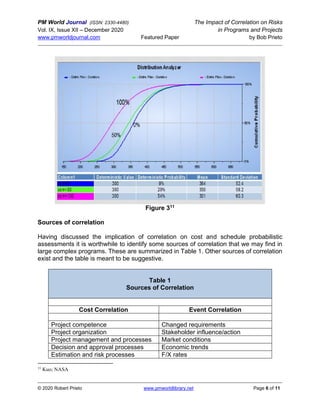

The paper by Bob Prieto discusses the significance of considering correlation in cost and schedule risk assessments for projects and programs. It highlights that failing to account for correlation can lead to substantial underestimations of total cost variance, especially in complex programs with multiple projects where dependencies exist. Key recommendations include treating correlations realistically, using suitable distributions for cost analysis, and recognizing the impacts of various biases and systemic factors.