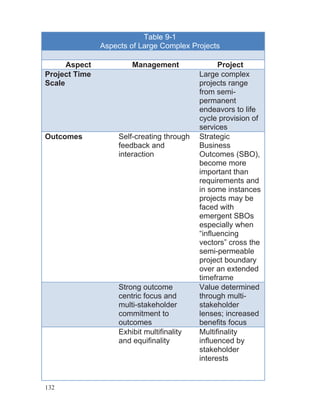

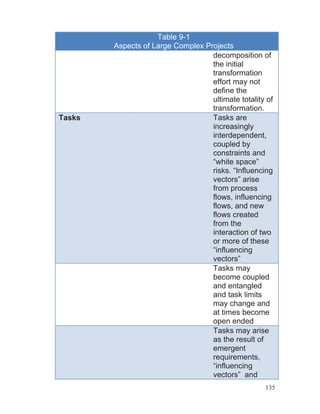

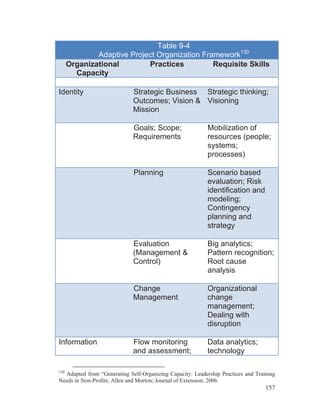

The document explores the evolving theory of management concerning large complex projects, emphasizing the need to integrate general management practices with project management. It identifies critical attributes such as long time scales, multi-stakeholder engagement, and the impact of emergent factors on project outcomes, suggesting a shift towards an outcomes-focused approach rather than an outputs-driven one. Additionally, it highlights the significance of stakeholder roles and managing flows across semi-permeable boundaries, which are crucial for successful project execution and adaptability.