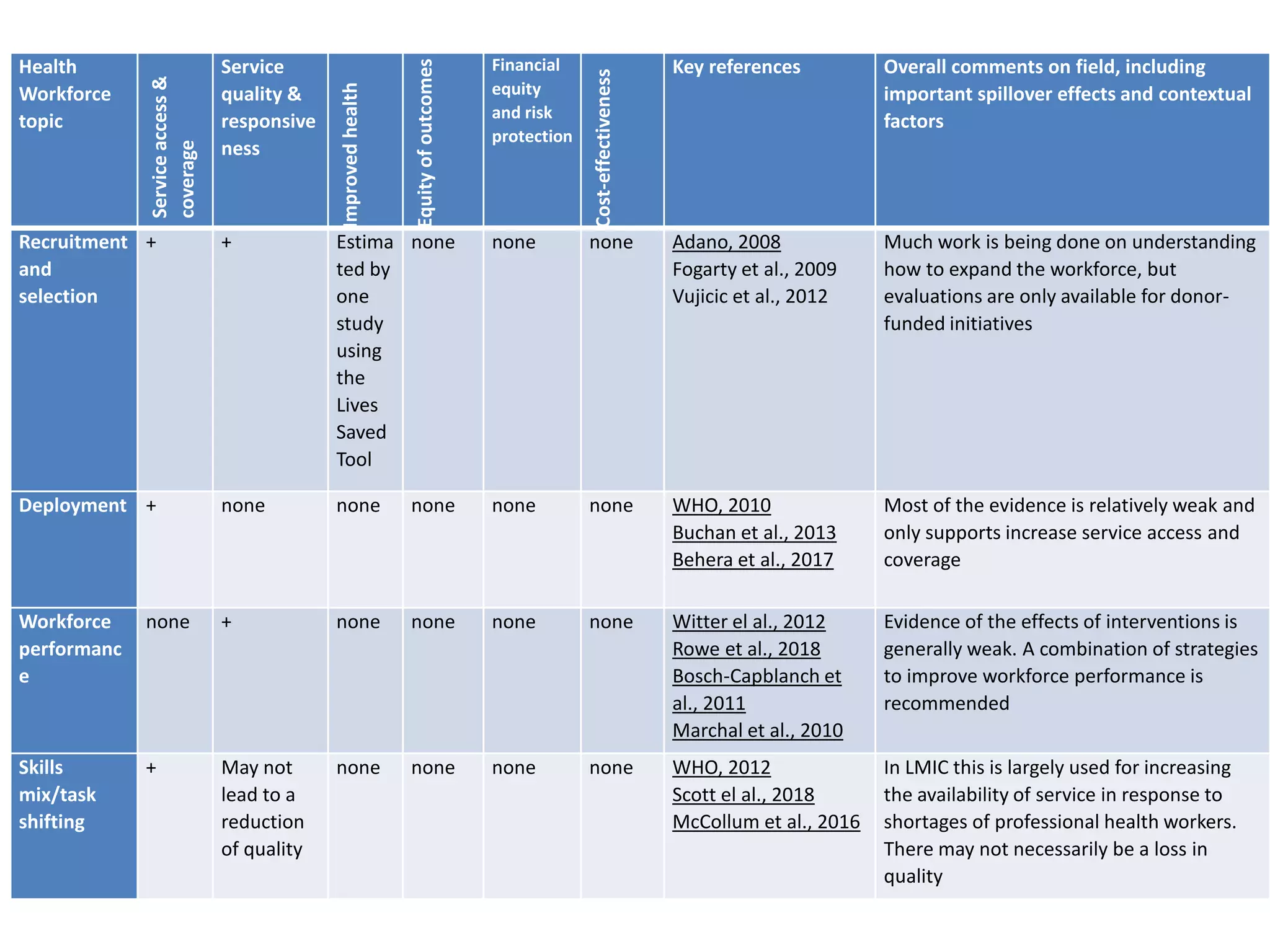

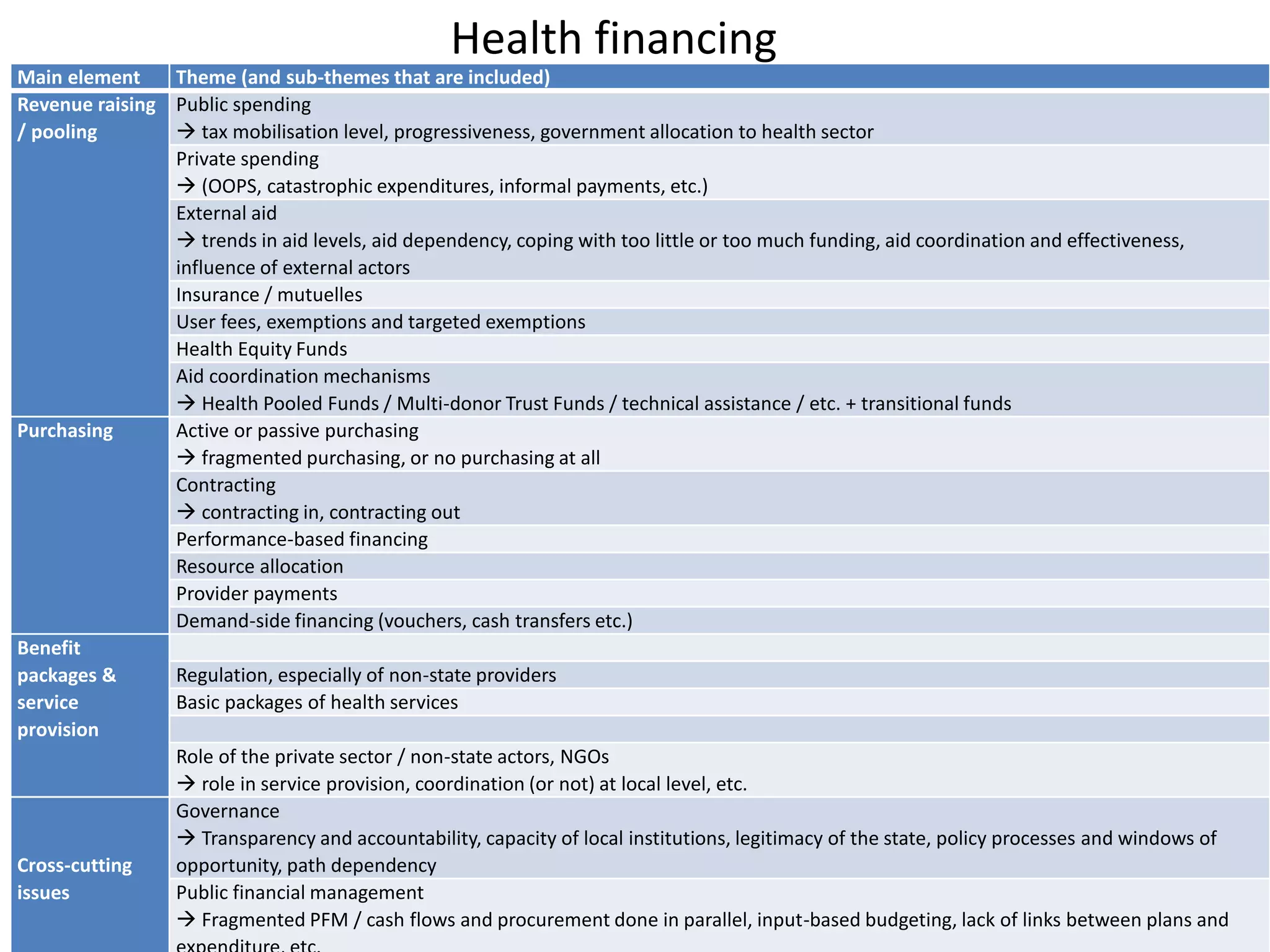

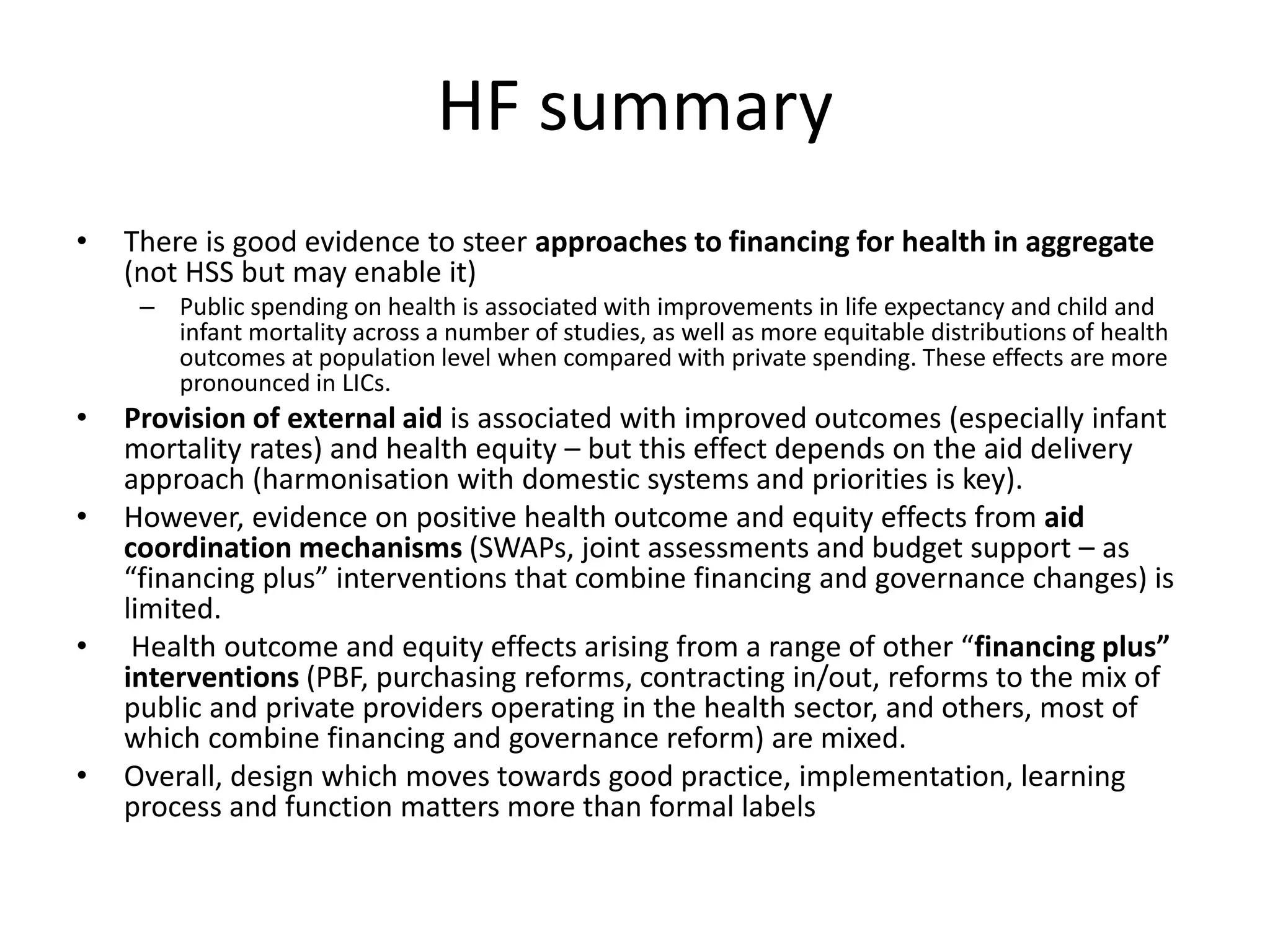

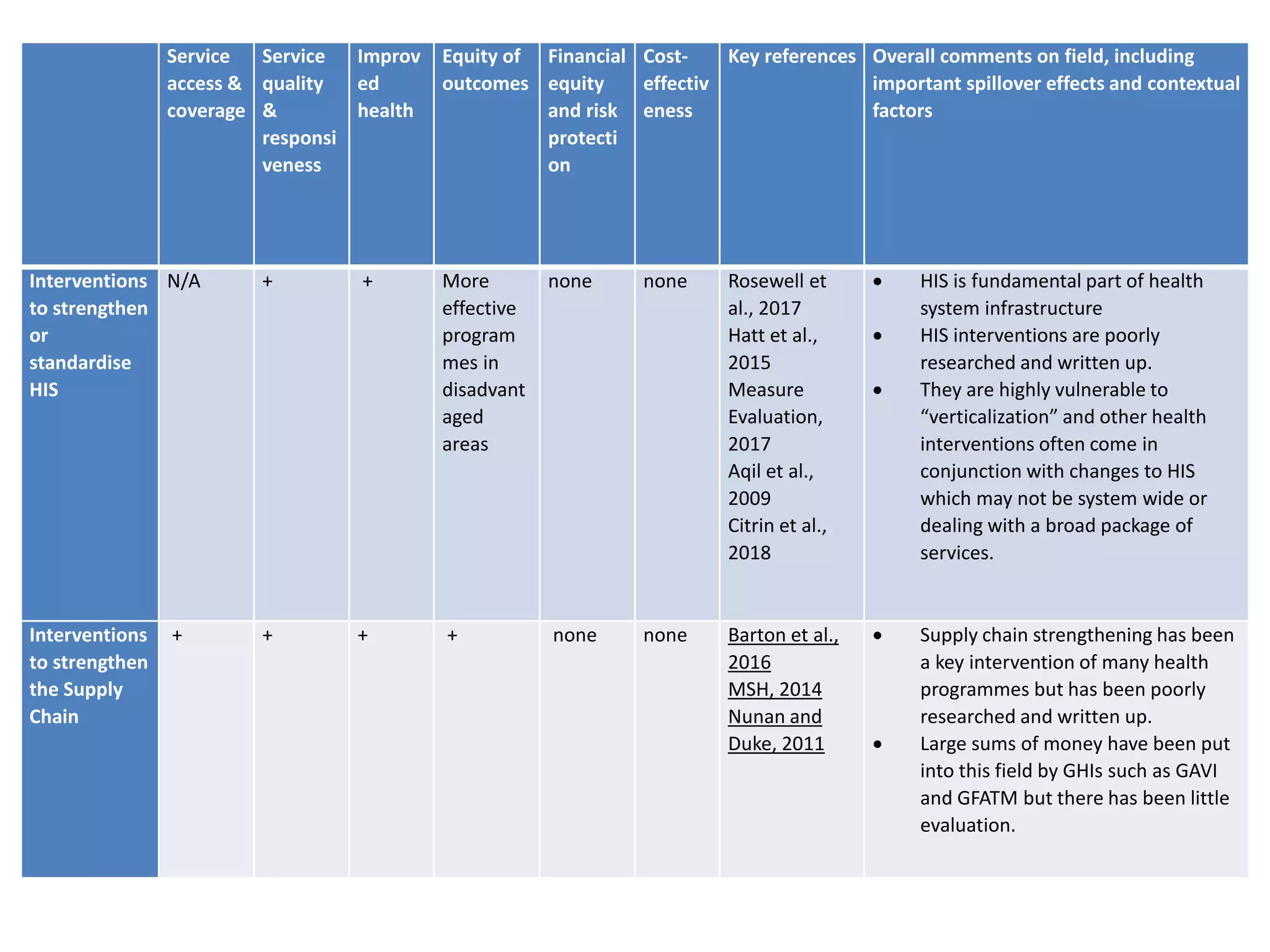

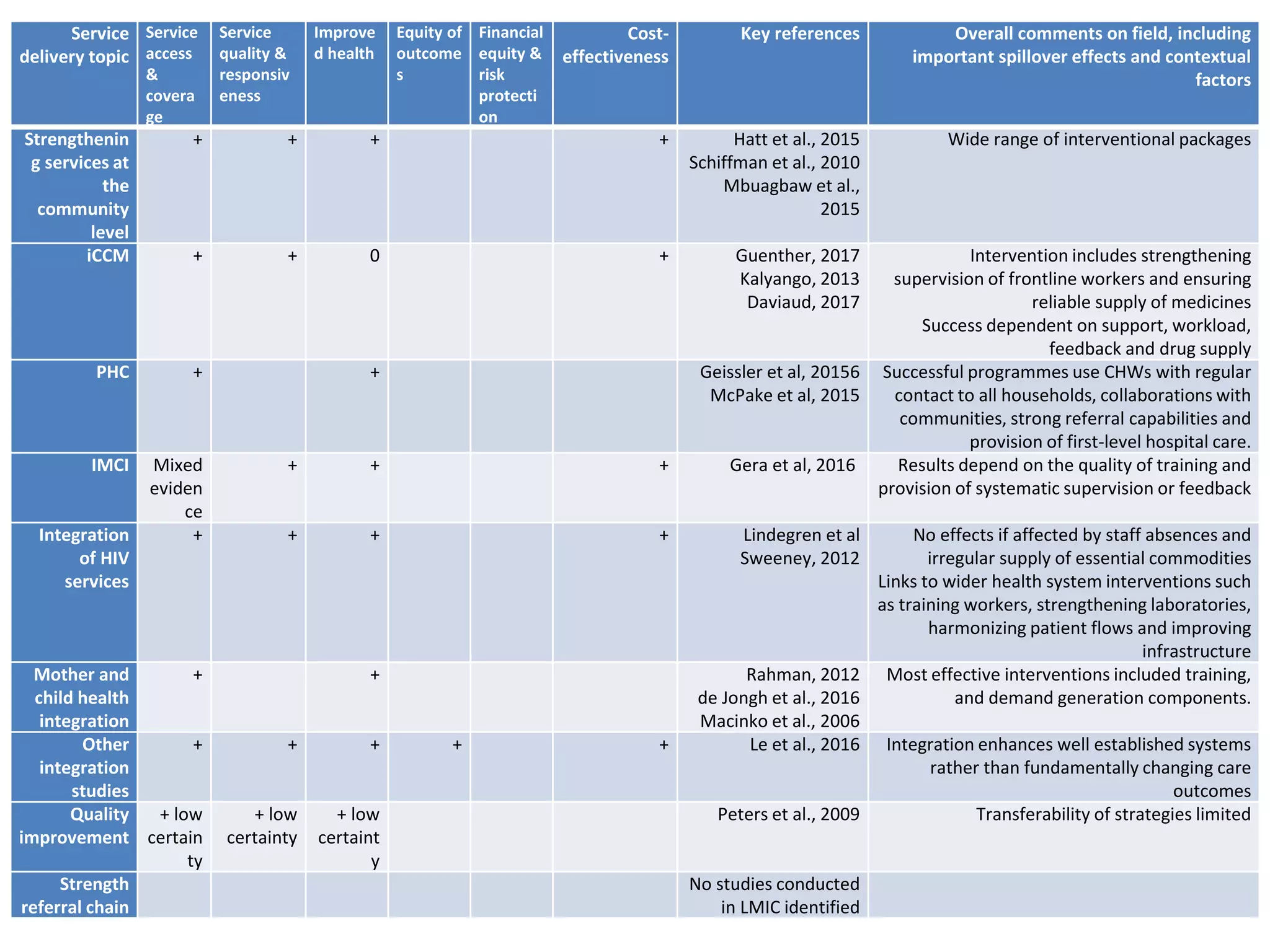

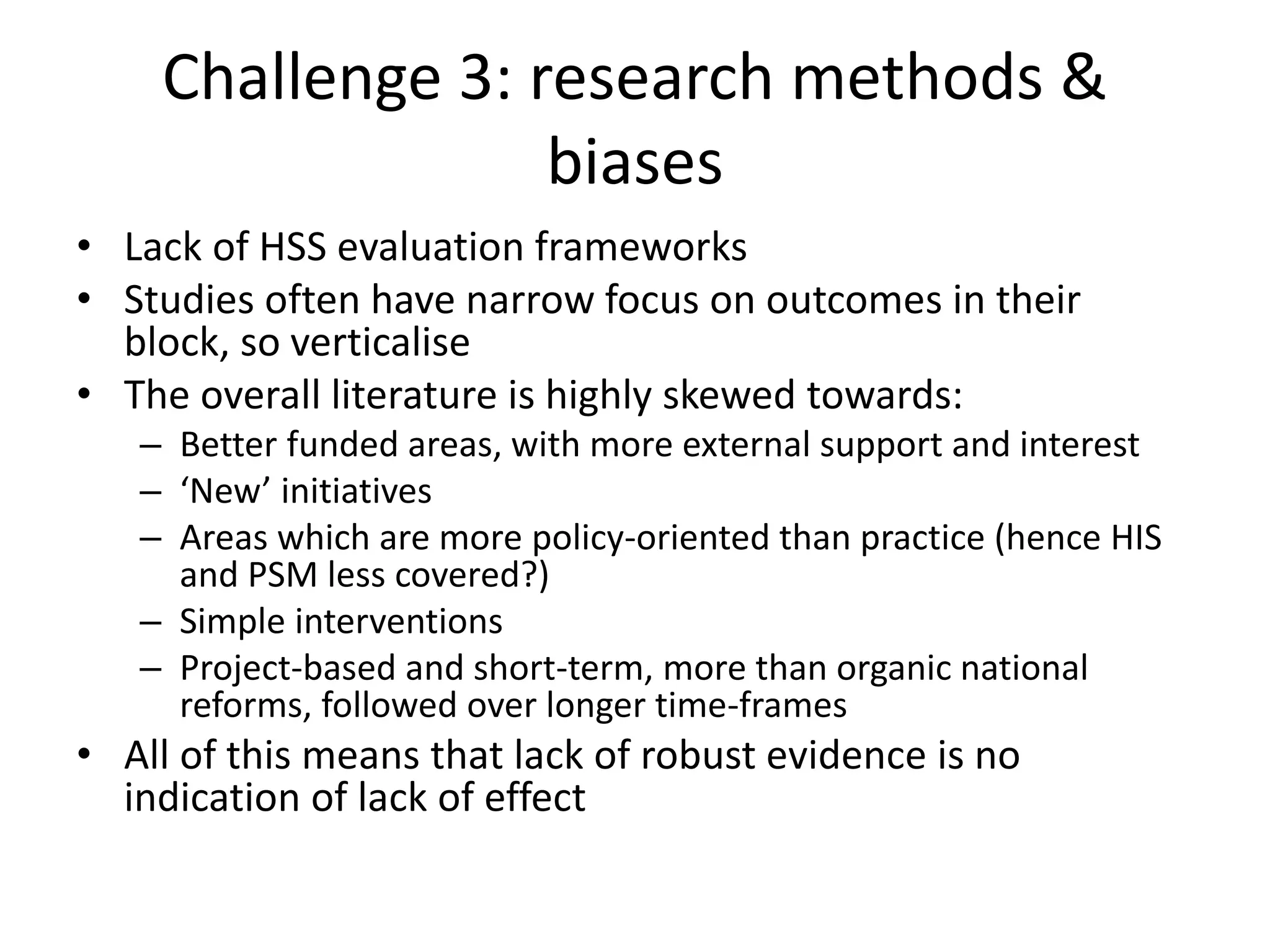

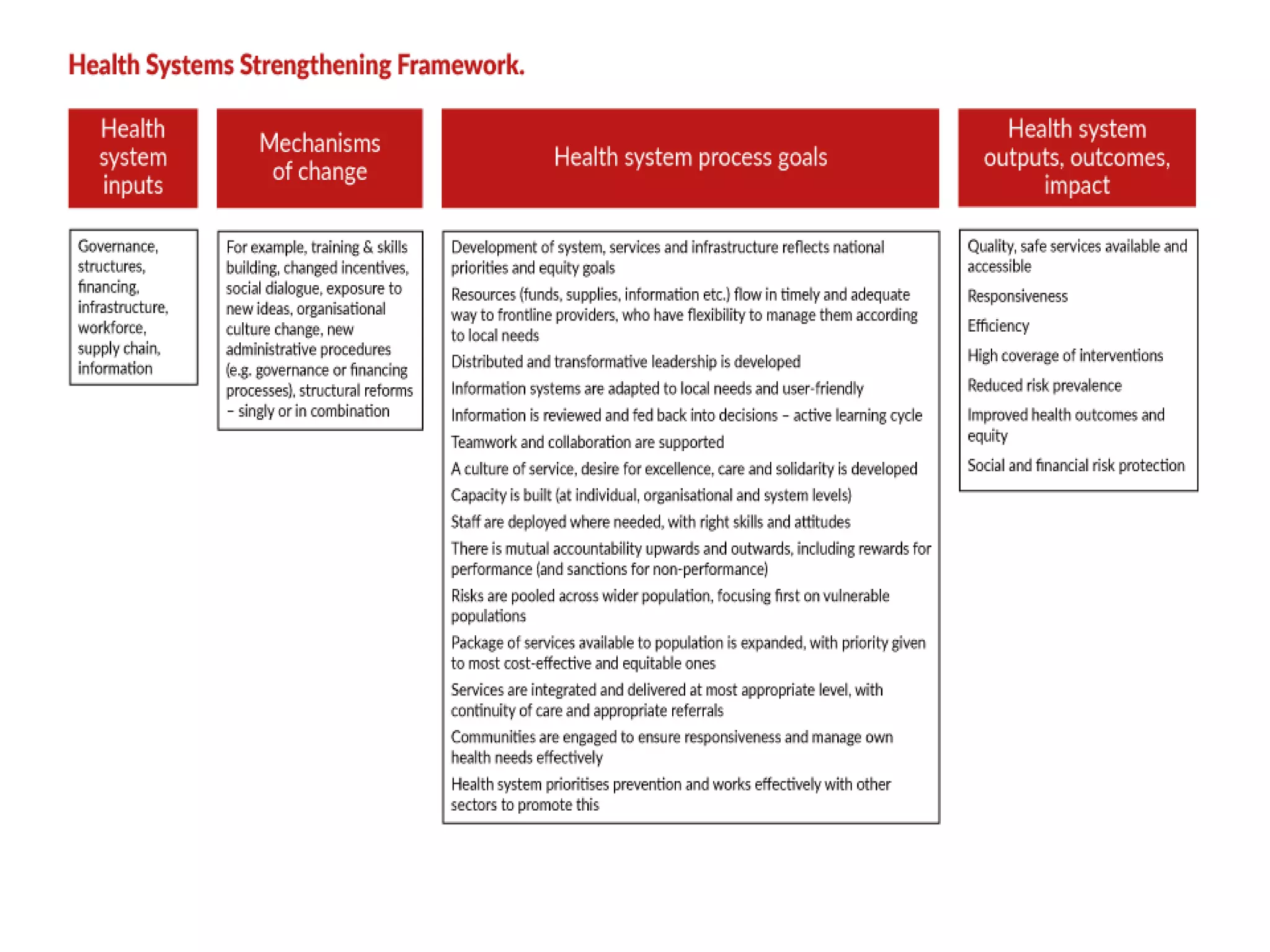

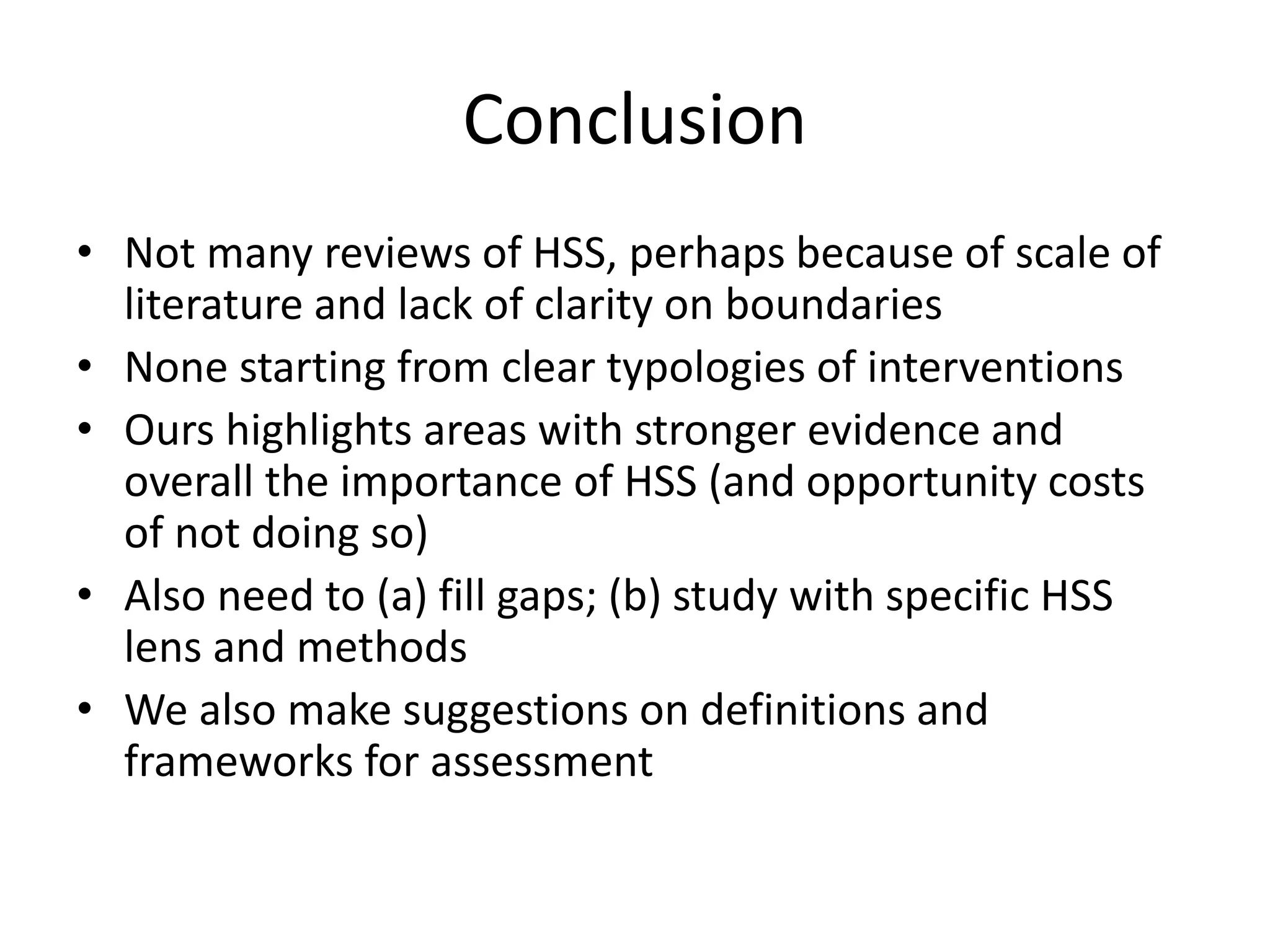

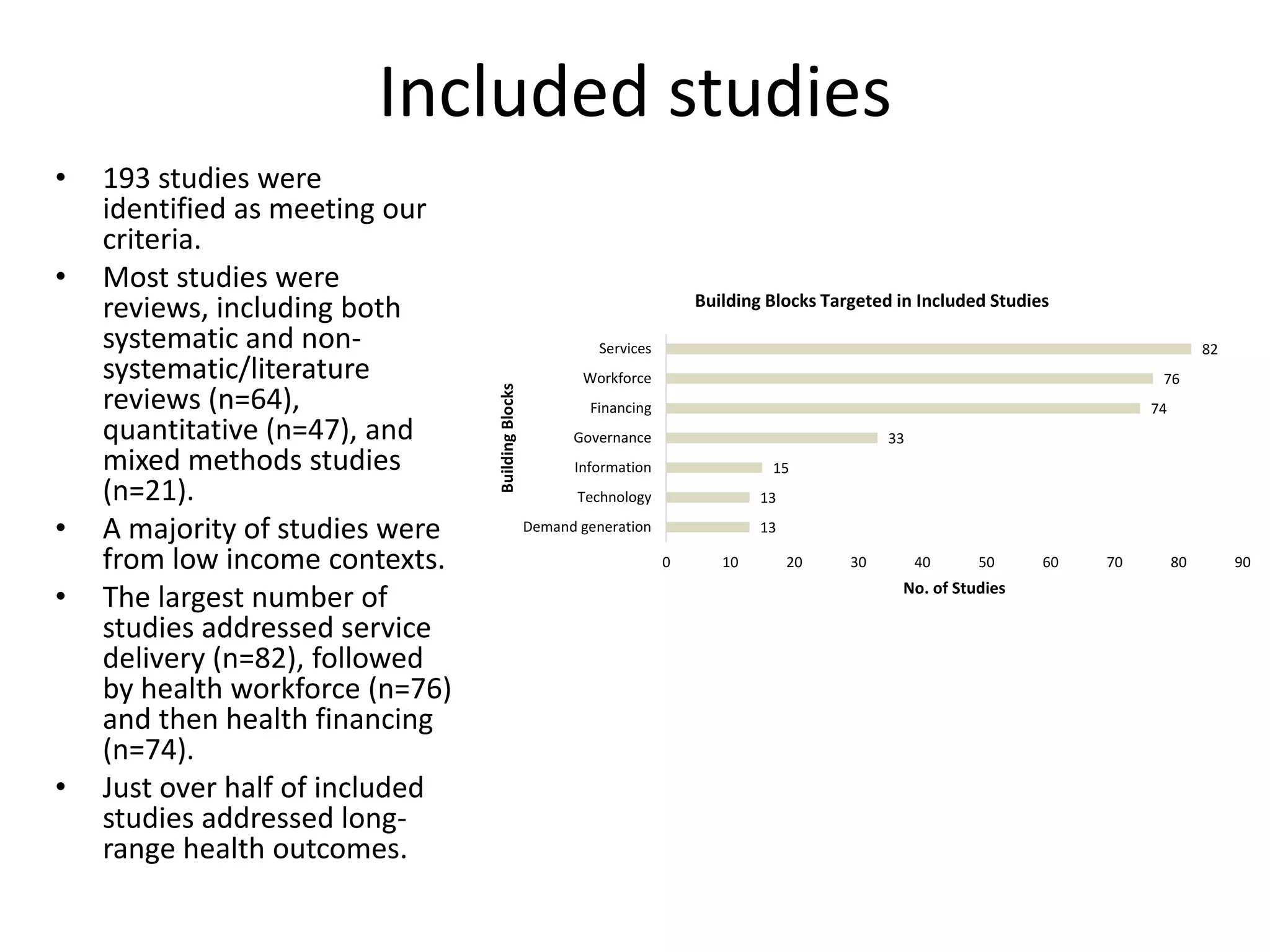

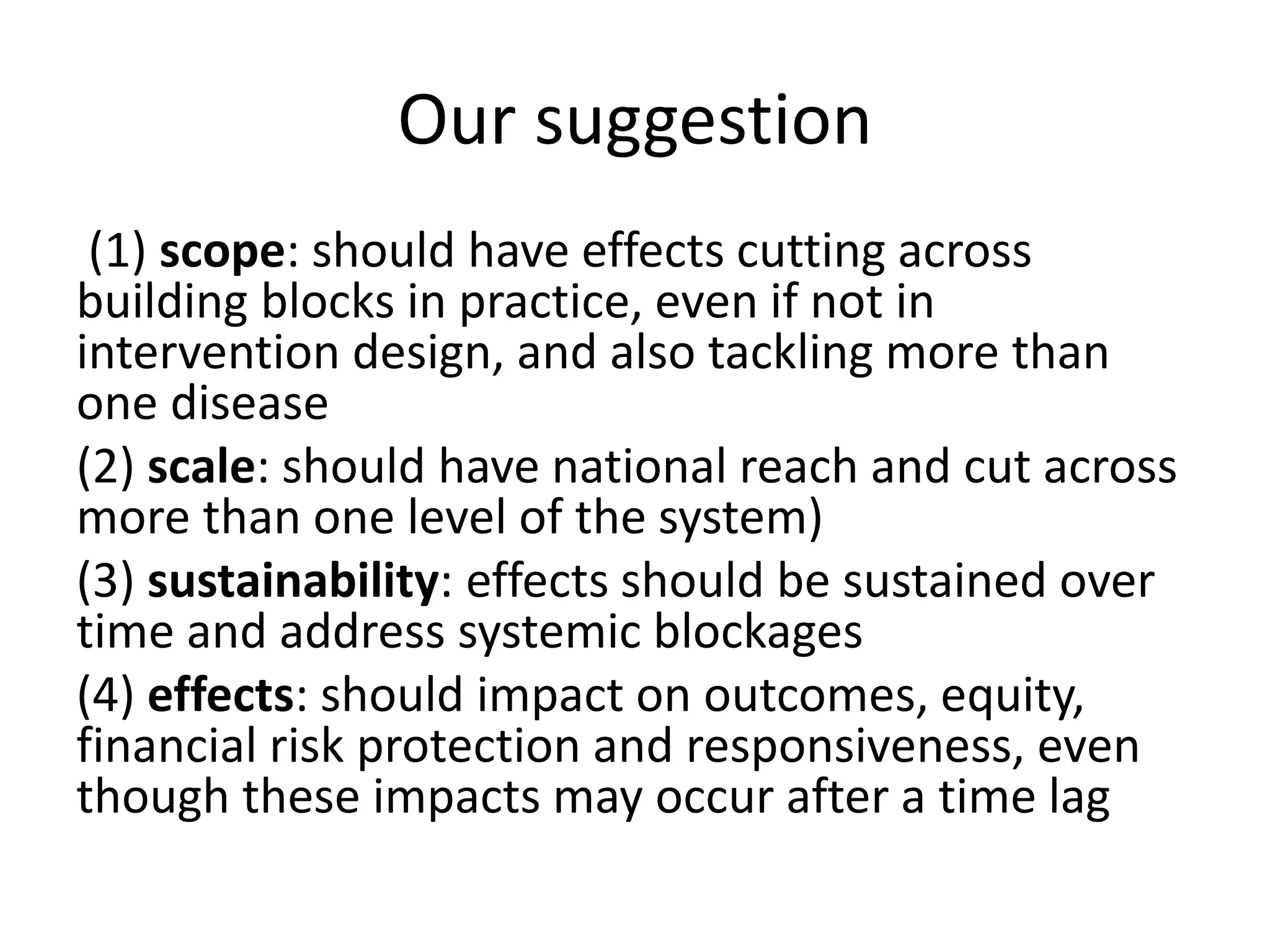

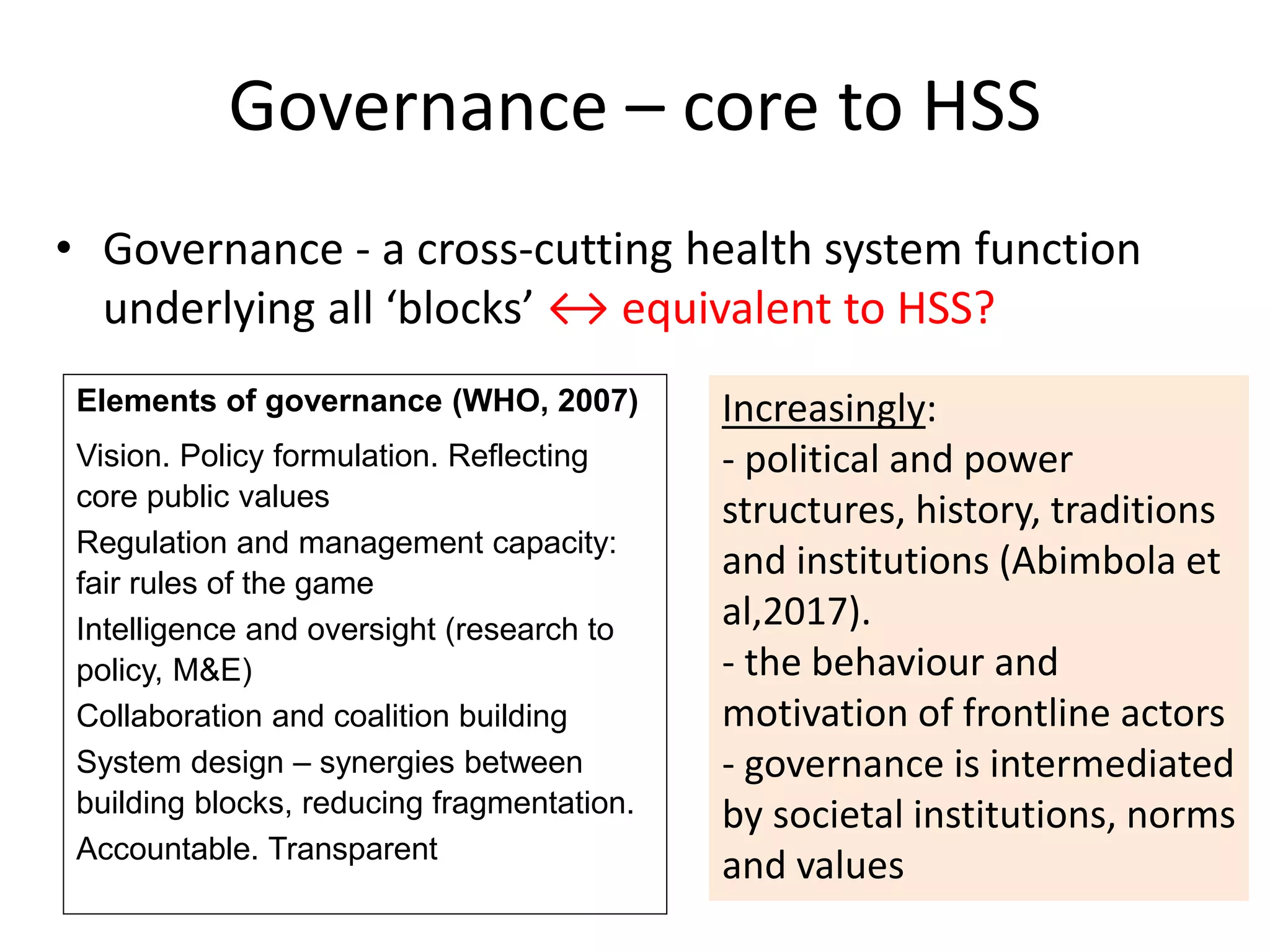

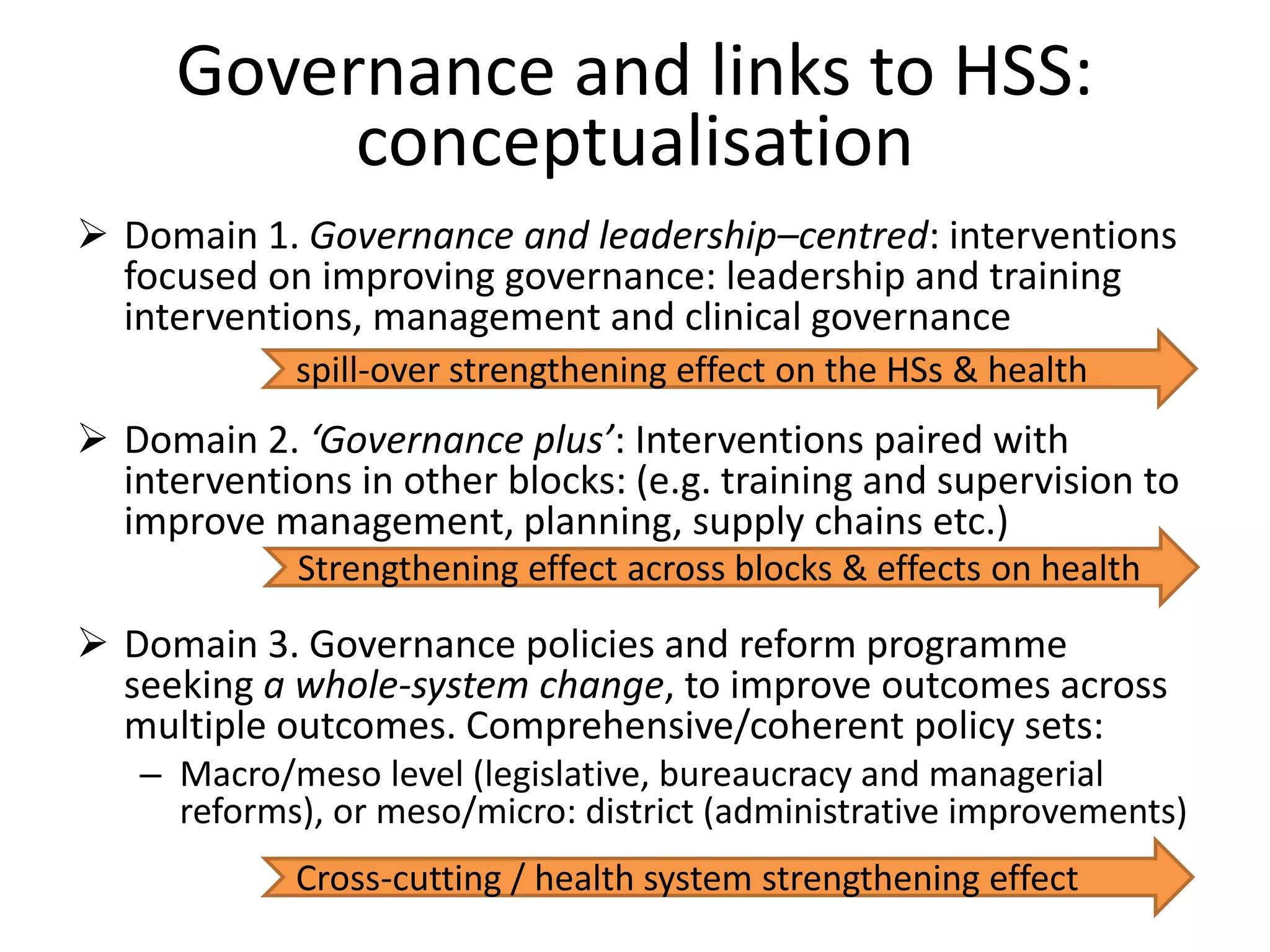

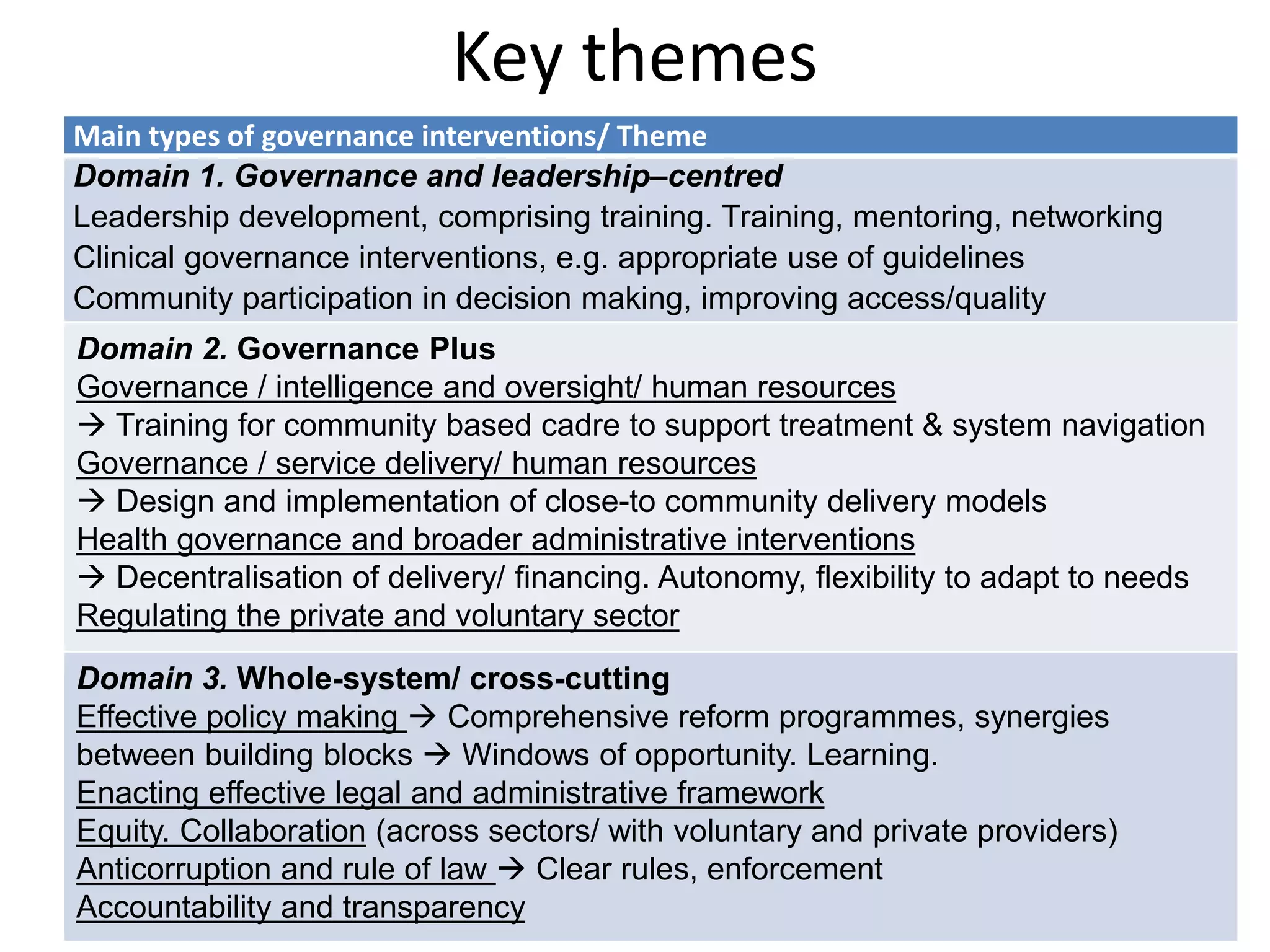

The document discusses health system strengthening (HSS), emphasizing its definition, assessment methods, and effectiveness in various contexts, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. It identifies challenges in evaluating HSS, outlines key governance and service delivery elements, and highlights the need for integrated approaches across multiple health system blocks to achieve sustainable improvements in health outcomes. The findings suggest that robust, context-sensitive evaluations and a deep understanding of the existing systems are crucial for HSS success.

![Governance: selected findings

• Whole-system change: comprehensive HSS identify good

governance within complex, system-wide reform programmes

achieve impact across outcomes [7 studies, e.g. the Good Health at Low

Cost study)

– collaborative working, long-term strategic reforms across all levels of the

health system, using windows of opportunity

• Governance-focused interventions (civil participation and engaging

community members with health service structures) improve

health, uptake and quality of care (e.g. MCH)

• Leadership programmes blending skills development, mentoring

and teamwork improve service quality, management

competence and motivation [Bhoma, effect but sustained]

• Mixed evidence on decentralisation: can be promoting or

obstructing depending on the quality of management and

wider political processes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hssfordfid300719-190731093522/75/Health-system-strengthening-what-is-it-how-should-we-assess-it-and-does-it-work-12-2048.jpg)