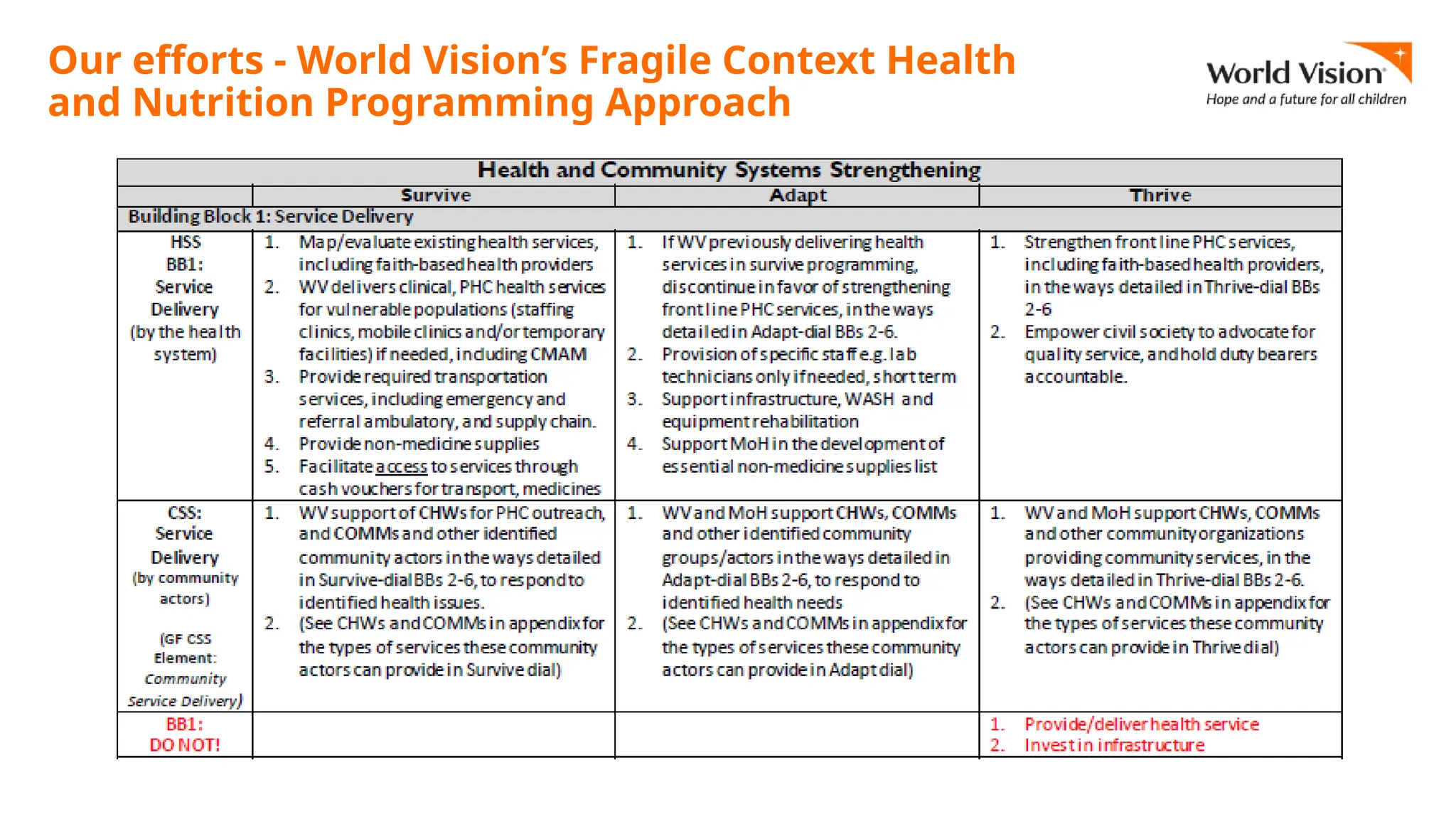

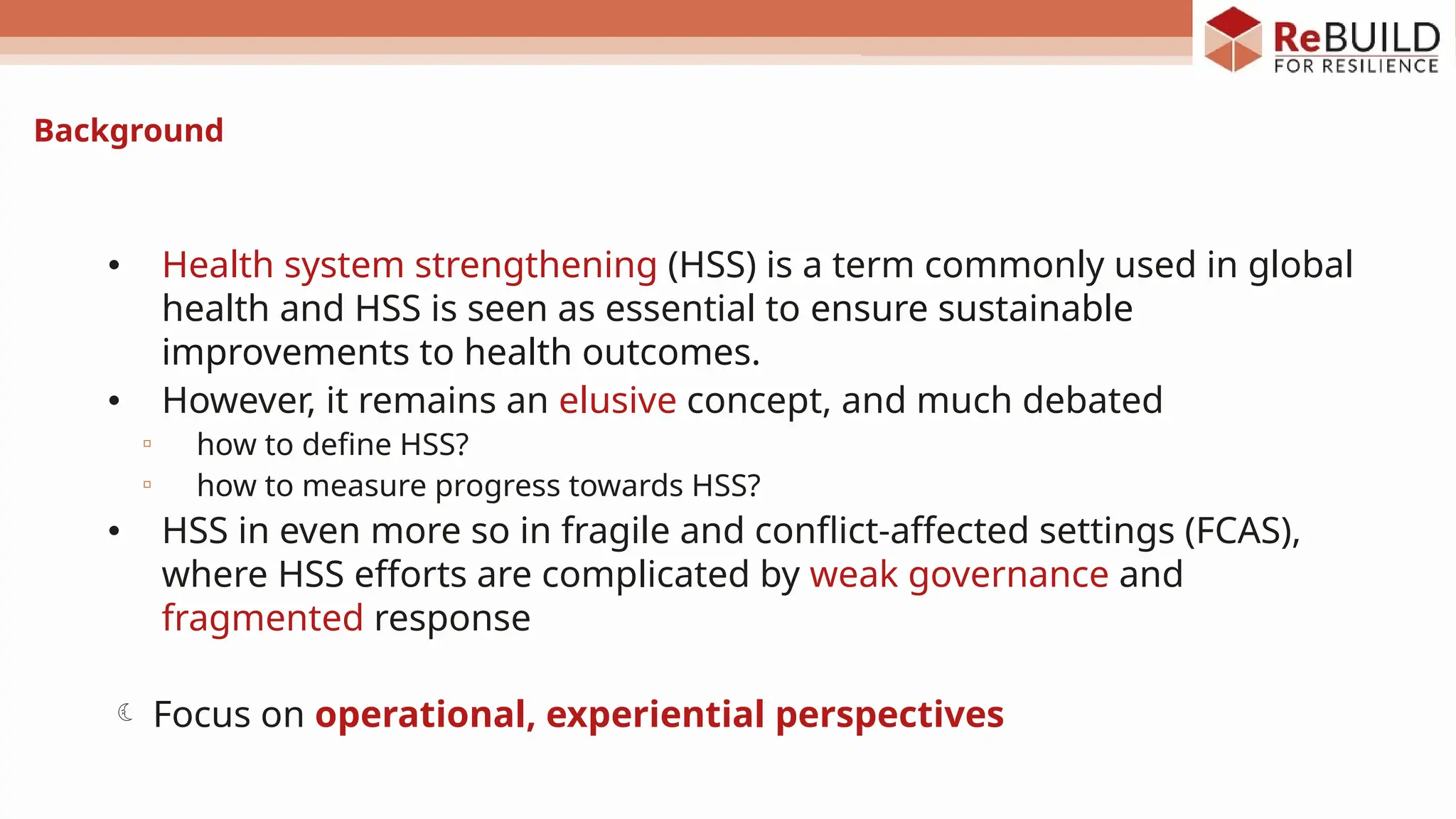

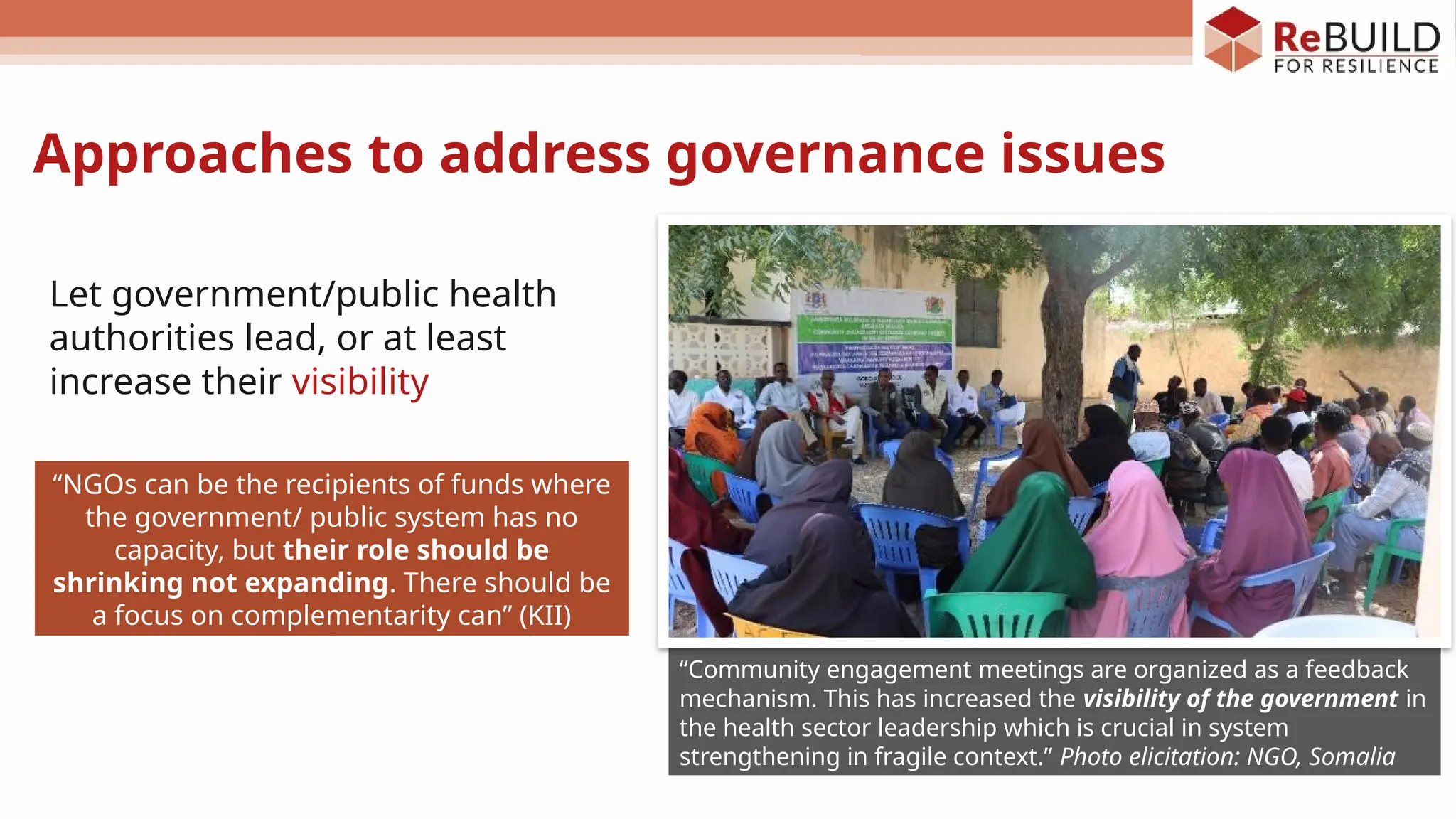

The document discusses health systems strengthening (HSS) in fragile and conflict-affected settings (FCAS), highlighting the operational experiences and challenges faced by NGOs in these contexts. It synthesizes findings from key informant interviews, emphasizing the need for flexibility, better governance, and integration between humanitarian and development efforts. The session aims to foster discussion on promoting effective HSS programming in FCAS while addressing critical gaps and challenges.

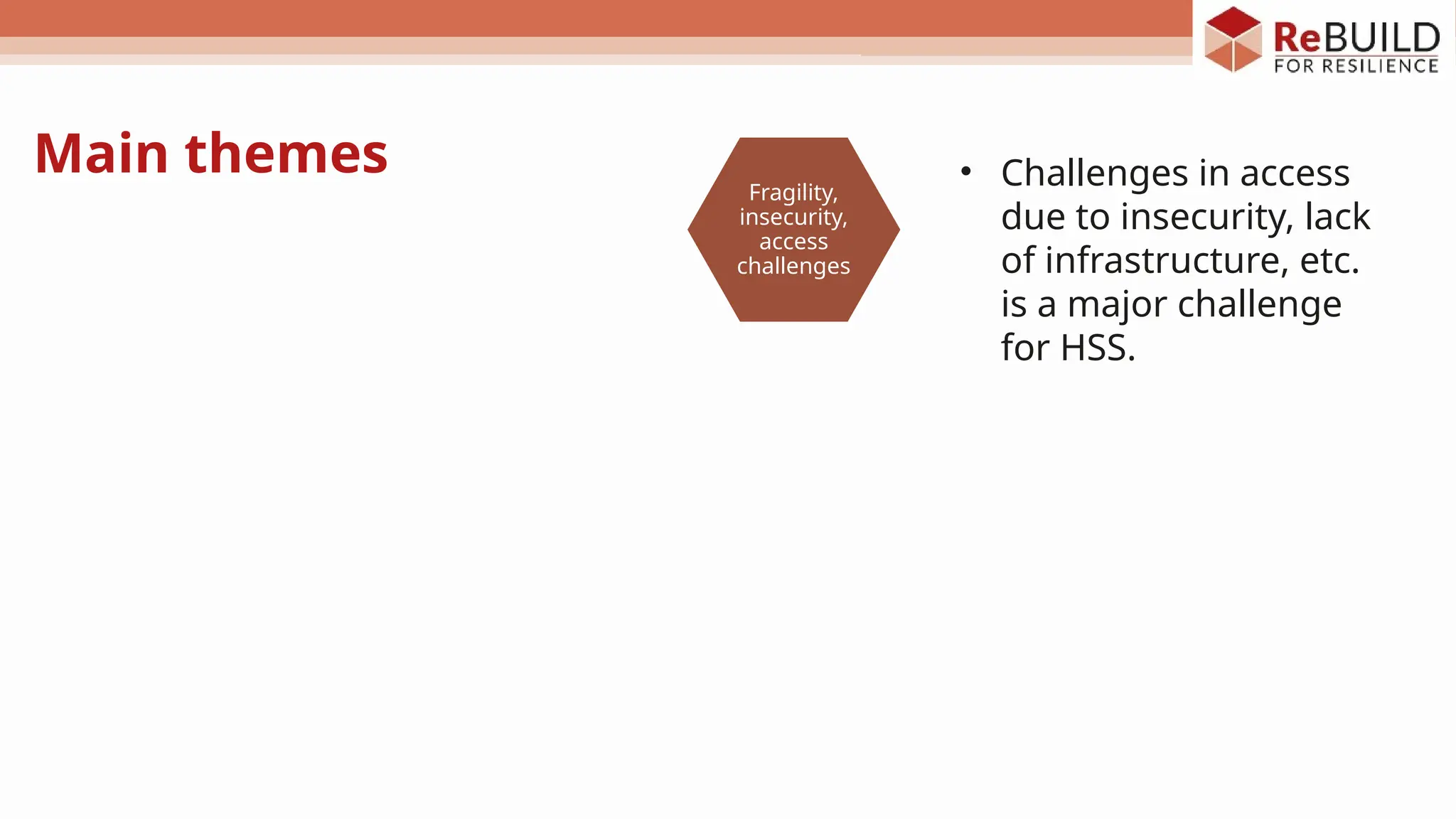

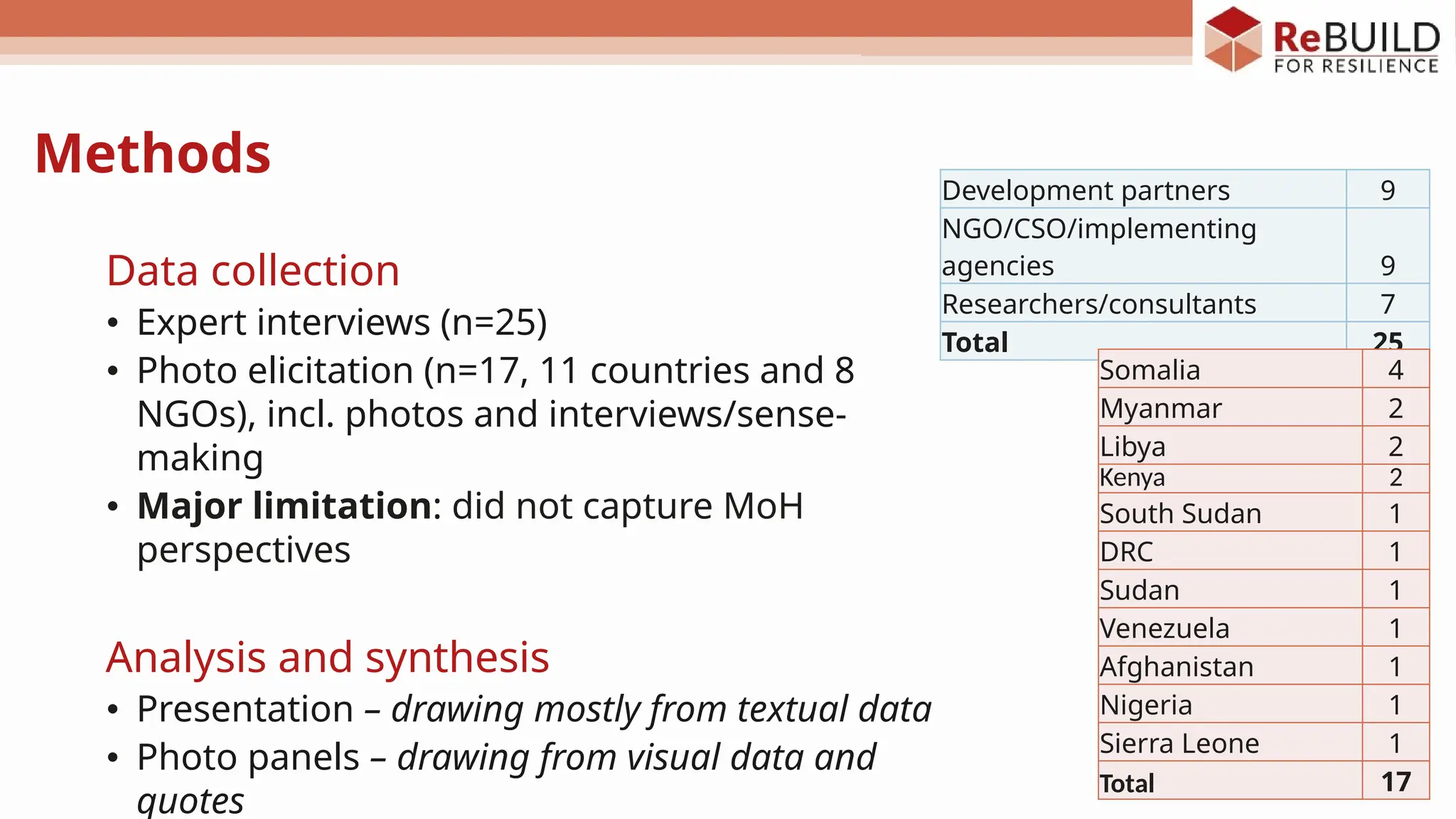

![• Potential to leverage the

humanitarian phase for HSS

• In some cases, crisis can even

provide windows for reforms / HSS:

▫ COVID-19

▫ Ukraine

▫ Vulnerabilities are more visible

“We need to have a clear understanding of what is

possible in each setting. We have to be realistic

about what is possible in terms of HSS. It is very

contextualised” (KII).

“It is important not to overestimate the priority of

HSS in humanitarian contexts, where the priority is

saving lives. Humanitarian actors are happy to use

existing systems where possible, but gaps are

sometimes too big. NGOs need to deliver, so having

to hire externally or bringing their own systems

might be needed” (KII).

• Priority is saving lives

• Focus on service delivery and

health system support at most “Emergencies are cyclical in a setting like eastern

DRC. We need to be able to capitalise on the

emergency response for HSS” (KII)

“Humanitarian actors are not mandated to do HSS

but [should] at least “do no harm”” (KII)

Fragility, insecurity, humanitarian priorities](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hssinfcassatellitesession-241203134319-148643d5/75/Health-System-Strengthening-in-Fragile-Conflict-Affected-Settings-19-2048.jpg)

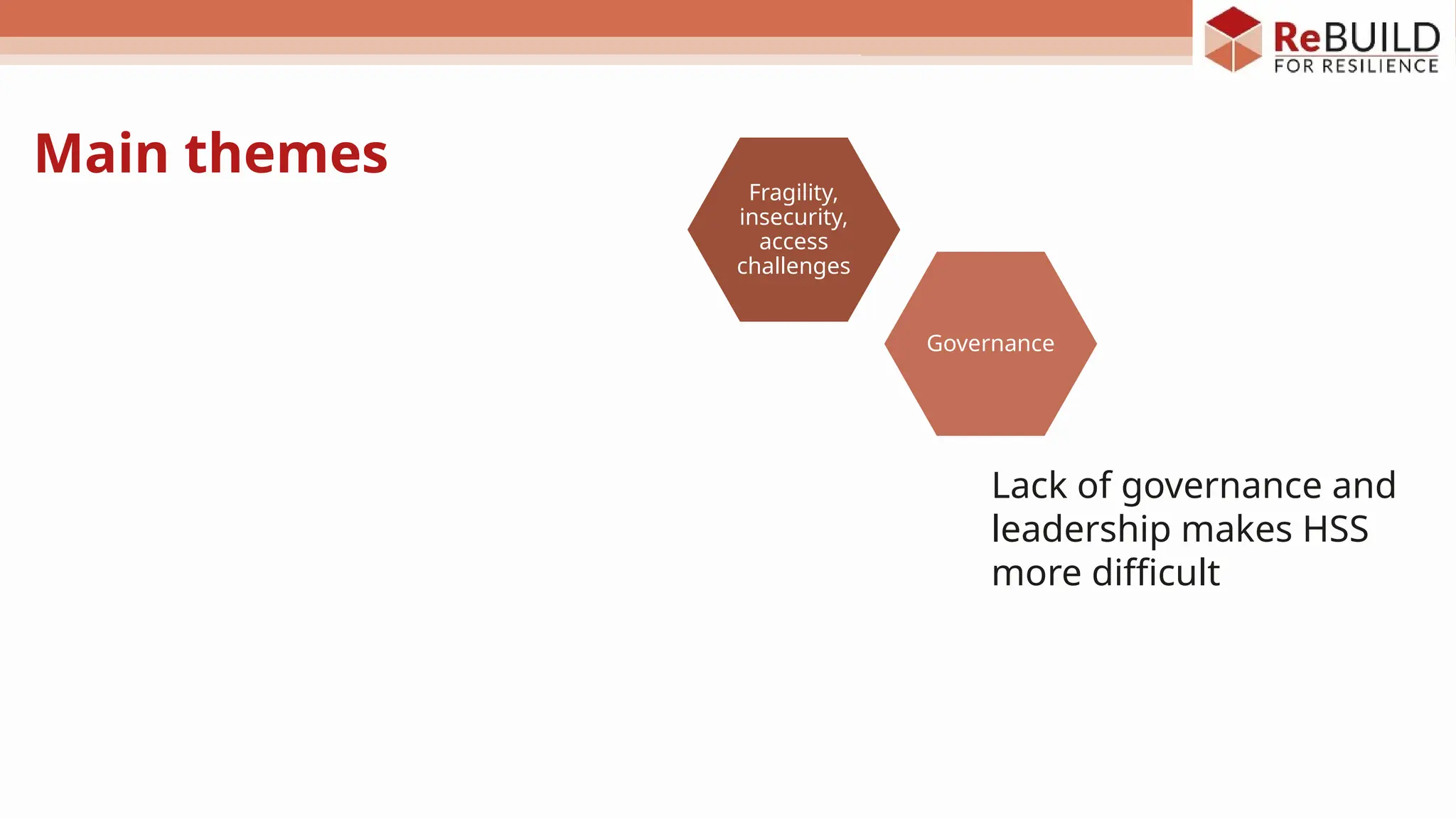

![Governance

• Lack of political peace and weak

governance and leadership make HSS

more difficult.

▫ Governments are weak, absent or multiple,

not legitimate (internally or externally), etc.

• HSS somewhat assumes the existence of a

single, national government and a public

health system as a precondition, what can

be done without it?

• Even more fundamentally, if there is no

government leadership/stewardship, how

can local ownership be fostered which

would make interventions sustainable?

“We are trying to build capacity at all

levels in case the transition [to

Government ownership] has to happen,

but the Somali government is very

politically fragmented, for any

activities there is the need for a lot of

negotiations, to sit with them at

different levels and multiple times, to

bring all to the table”. Photo elicitation:

NGO, Somalia](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hssinfcassatellitesession-241203134319-148643d5/75/Health-System-Strengthening-in-Fragile-Conflict-Affected-Settings-21-2048.jpg)

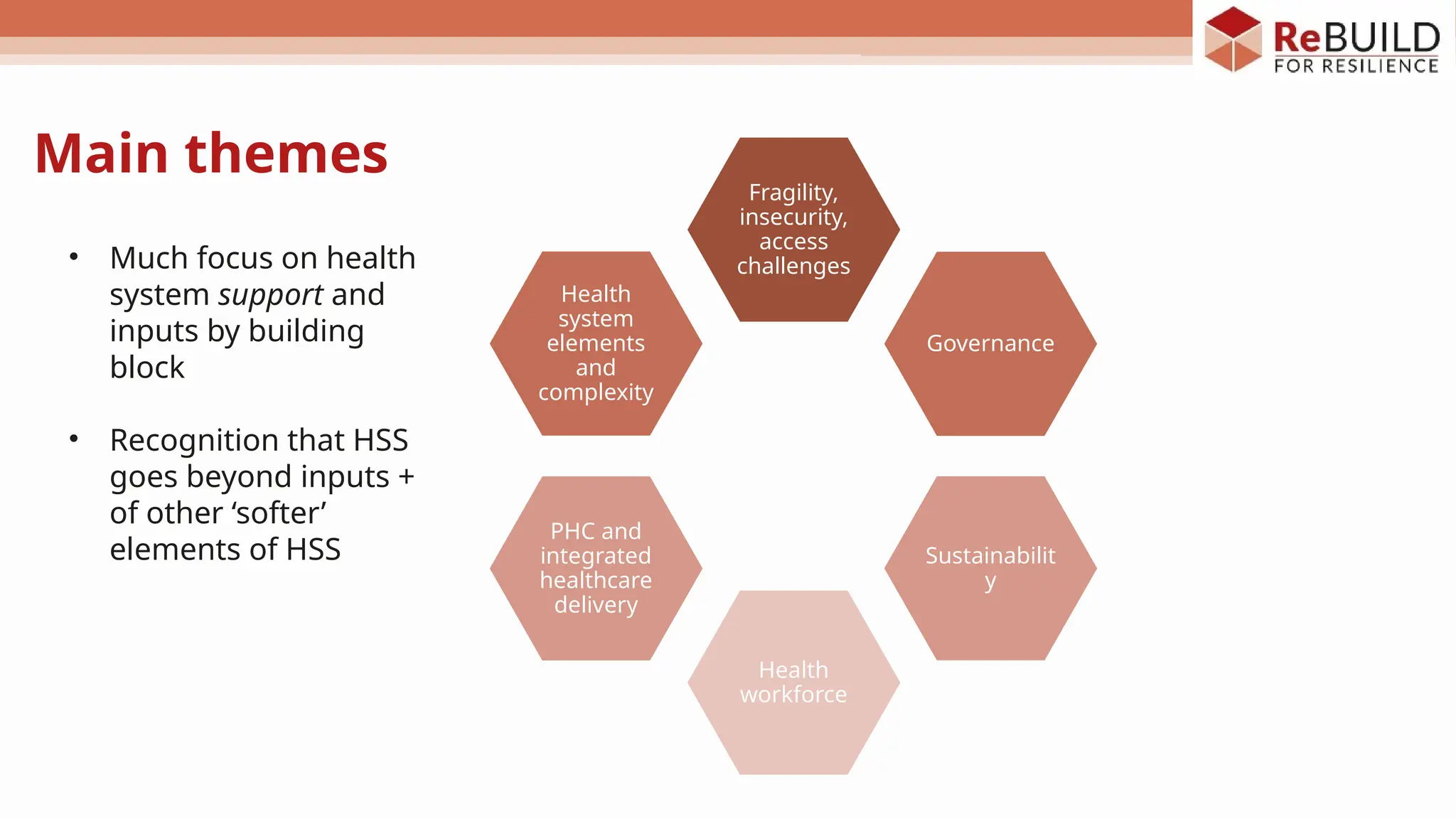

![• NGOs are not better placed for HSS and

taking the “strategic view”

• They needs supportive structures and a

clear set of incentives from funders to be

able to facilitate/do HSS

• There is also need for more understanding

and capacity building around HSS

▫ Varying definitions and level of

conceptual reflections

▫ Also reflecting mandates and funding

sources (e.g. humanitarian or GHI

funding)

Role of NGOs

“NGOs have more competence in service delivery and

less in working across the building blocks. Is [HSS]

really their role? They can’t work if [governance]

structures are not well set up. But at the same time, is it

their role to do it [set up governance structures]?” (KII).

“We can’t expect NGOs to be strategic at such high level

(...). But they can be involved in the discussions to

ensure empowerment, allow them to contribute to the

debate and share their learnings, ask donors to set the

right incentives for NGOs” (KII).

“Donors should allow, NGOs should do” (KII).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/hssinfcassatellitesession-241203134319-148643d5/75/Health-System-Strengthening-in-Fragile-Conflict-Affected-Settings-29-2048.jpg)