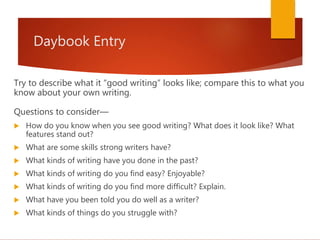

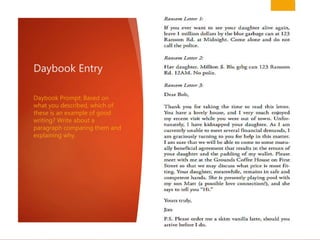

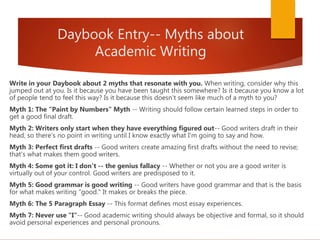

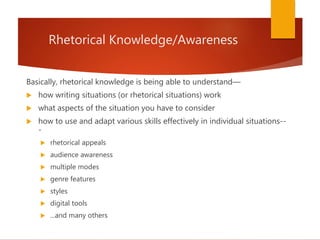

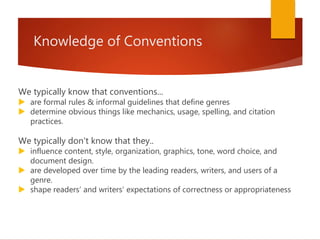

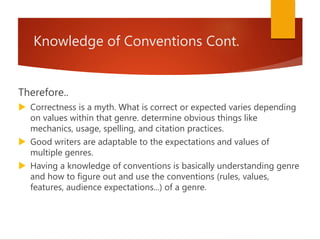

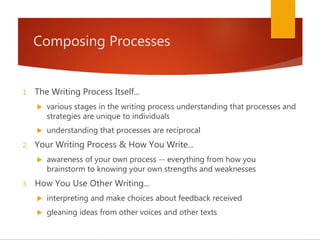

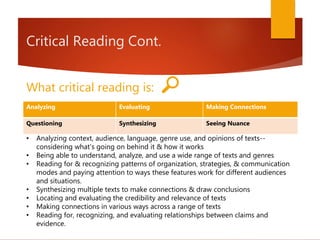

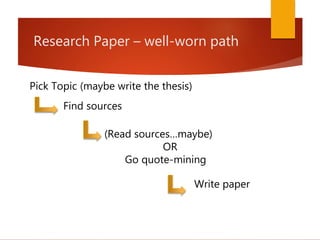

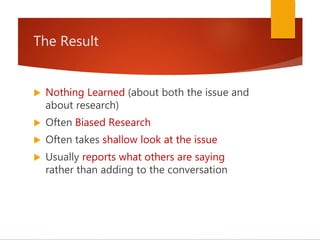

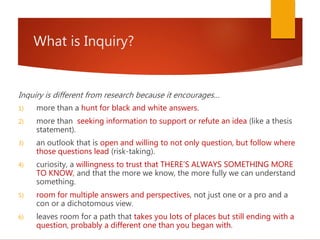

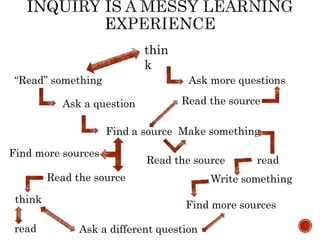

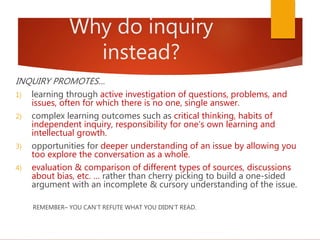

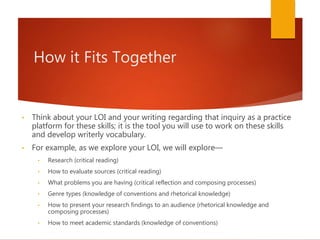

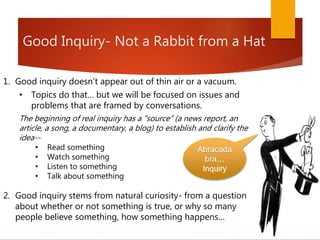

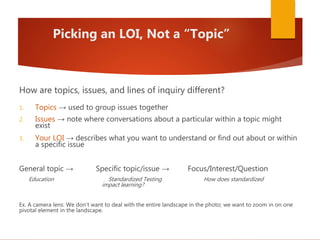

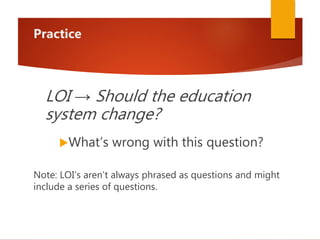

The document outlines key concepts and skills necessary for good writing, emphasizing the importance of rhetorical knowledge, critical reading, and inquiry in the writing process. It debunks common myths about academic writing and stresses the need for adaptability to various genres and conventions. The focus is on fostering critical thinking through inquiry, encouraging students to engage deeply with their writing and research topics.