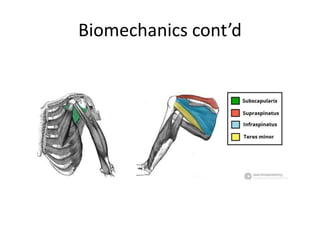

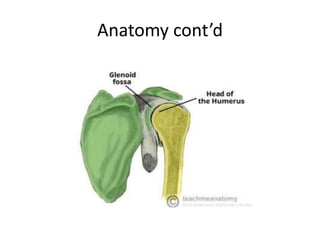

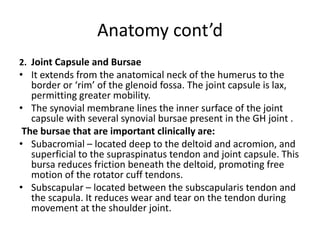

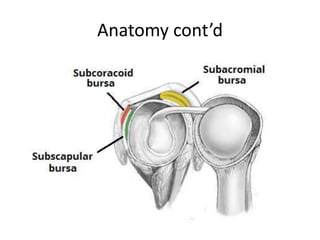

The document describes the anatomy and biomechanics of the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint. It discusses the joint's articulating surfaces, ligaments, muscles, and neurovasculature that allow for its wide range of motion. It also notes the joint's inherent instability due to disproportionate bone surfaces and its susceptibility to anterior dislocation when excessive forces are applied. Common injuries like rotator cuff tendinitis and impingement are explained. The key takeaway is that the shoulder joint has great mobility but low stability, making it prone to dislocation, especially anteriorly into the weak anterior-inferior joint capsule.

![Anatomy cont’d

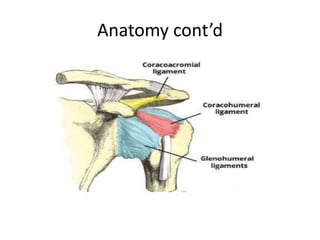

3. Ligaments

• Glenohumeral ligaments (superior, middle and inferior) – the

joint capsule is formed by this group of ligaments. They are

the main source of stability holding the shoulder in place and

preventing it from dislocating anteriorly.

• Coracohumeral ligament – attaches the base of the coracoid

process to the greater tubercle of the humerus. It supports

the superior part of the joint capsule.

• Transverse humeral ligament – spans the distance between

the two tubercles of the humerus. It holds the tendon of the

long head of the biceps in the intertubercular groove.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/glenohumeraljoint-201102062705/85/Glenohumeral-joint-8-320.jpg)