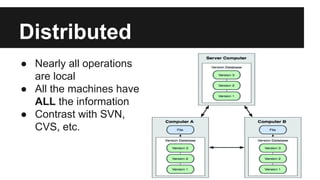

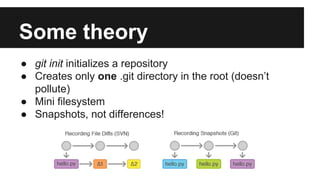

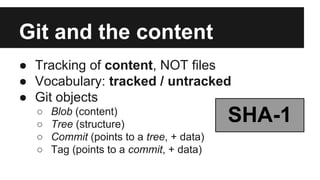

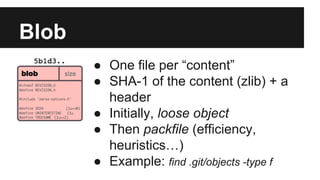

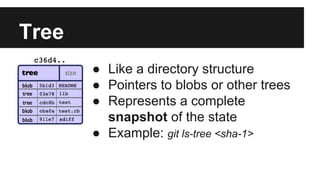

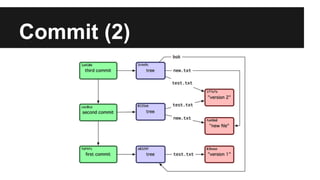

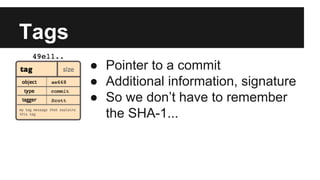

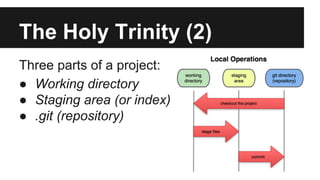

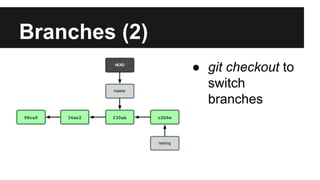

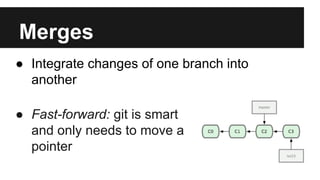

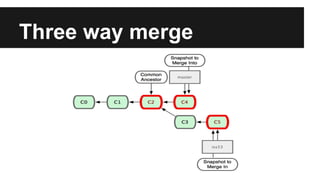

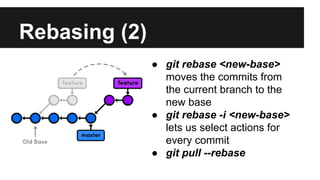

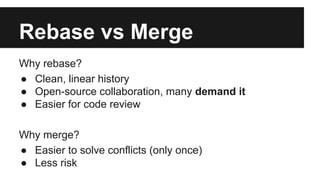

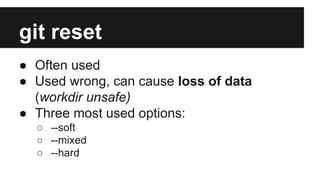

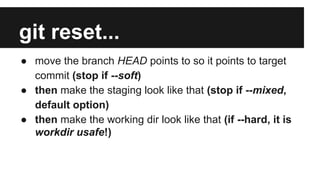

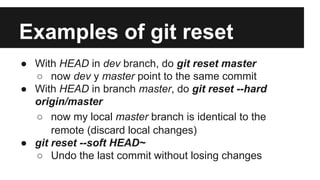

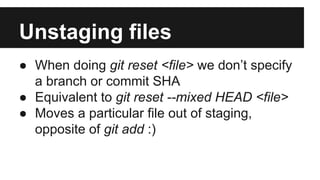

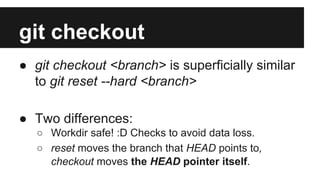

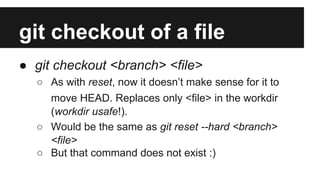

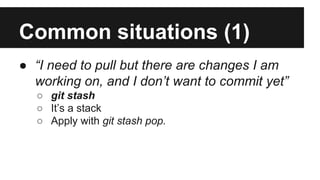

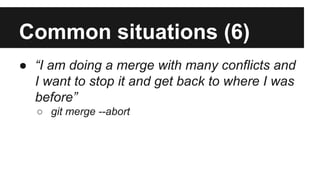

This document provides an overview of the goals, origins, basic concepts and commands of the Git version control system. It discusses how Git tracks content rather than files, uses SHA-1 hashes to store data efficiently in objects, and allows non-linear development through branches and distributed collaboration. The key concepts of the staging area, commits, branches, remotes and basic commands like add, commit, push and pull are explained. Common workflows like merging, rebasing and resolving conflicts are also covered.