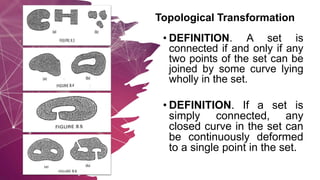

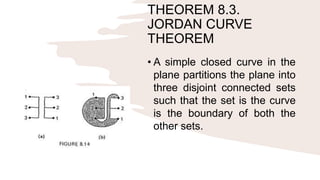

The document discusses several theorems in topological transformation and simple closed curves. It defines topological transformation as the study of properties of a set of points invariant under continuous transformations. It also examines theorems like the Jordan Curve Theorem, which states that a simple closed curve partitions the plane into an interior and exterior region.