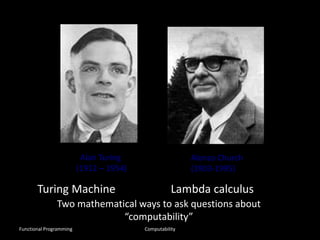

The document discusses functional programming and computability, focusing on concepts introduced by Alan Turing and Alonzo Church in the 1930s, including Turing machines and lambda calculus. It outlines the Entscheidungsproblem, which seeks algorithms to determine the truth of statements in first-order logic, and highlights Turing's assertion that there are well-defined problems that cannot be solved by computational procedures. The document further emphasizes the relationship between computation models and the Church-Turing thesis, asserting that both Turing machines and lambda calculus can compute the same functions.

![Equivalent Computers

z z zz z z z

1

Start

HALT

), X, L

2:

look

for (

#, 1, -

), #, R

(, #, L

(, X, R

#, 0, -

Finite State Machine

...

Turing Machine

term = variable

| term term

| (term)

| variable . term

y. M v. (M [y v])

where v does not occur in M.

(x. M)N M [ x N ]

Lambda Calculus

Functional Programming Computability](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionalbackground-150915104733-lva1-app6891/85/Computability-turing-machines-and-lambda-calculus-7-320.jpg)

![Alan Turing, 1936

• "On computable numbers, with an application

to the Entscheidungsproblem [decision

problem]”

• addressed a previously unsolved

mathematical problem posed by the German

mathematician David Hilbert in 1928:

Functional Programming Computability](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionalbackground-150915104733-lva1-app6891/85/Computability-turing-machines-and-lambda-calculus-8-320.jpg)

![Equivalent Computers

z z zz z z z ...

Turing Machine

term = variable

| term term

| (term)

| variable . term

y. M v. (M [y v])

where v does not occur in M.

(x. M)N M [ x N ]

Lambda Calculus

Functional Programming Lambda Calculus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionalbackground-150915104733-lva1-app6891/85/Computability-turing-machines-and-lambda-calculus-45-320.jpg)

![What is Calculus?

• In High School:

d/dx xn = nxn-1 [Power Rule]

d/dx (f + g) = d/dx f + d/dx g [Sum Rule]

Calculus

is a branch of mathematics

that deals with limits

and the differentiation and

integration of functions

of one or more variables...

Functional Programming Lambda Calculus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionalbackground-150915104733-lva1-app6891/85/Computability-turing-machines-and-lambda-calculus-46-320.jpg)

![Expression Reduction

Functional Programming Lambda Calculus

(𝛌x. x x) (𝛌y. y)

--> x x [𝛌y. y / x]

== (𝛌y. y) (𝛌y. y)

--> y [𝛌y. y / y]

== 𝛌y. y

How the original expression is

evaluated

Is determined the

operational semantics

of lambda calculus

(there are many ways to evaluate expressions)

Operational Semantics: how the substitutions are made:

Key concepts:

specification of free variables

specification of bound variables

Β-reduction

a formalization of simple substitution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionalbackground-150915104733-lva1-app6891/85/Computability-turing-machines-and-lambda-calculus-57-320.jpg)

![Example

(λx. x x) (𝛌y. y)

--> x x [𝛌y. y / x]

== (𝛌y. y) (𝛌y. y)

--> y [𝛌y. y / y]

== 𝛌y. y

Substitute (𝛌y. y) into x

Substituted

Substitute (𝛌y. y) into y

Substituted

Functional Programming Examples](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionalbackground-150915104733-lva1-app6891/85/Computability-turing-machines-and-lambda-calculus-62-320.jpg)

![Another example

(𝛌x. x x) (𝛌x. x x)

--> x x [𝛌x. x x/x]

== (𝛌x. x x) (𝛌x. x x)

In other words,

it is simple to write non terminating computations

in the lambda calculus

what else can we do?

Substitute 𝛌x. x x into every x

The result is the same as the beginning

Functional Programming Examples](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionalbackground-150915104733-lva1-app6891/85/Computability-turing-machines-and-lambda-calculus-63-320.jpg)