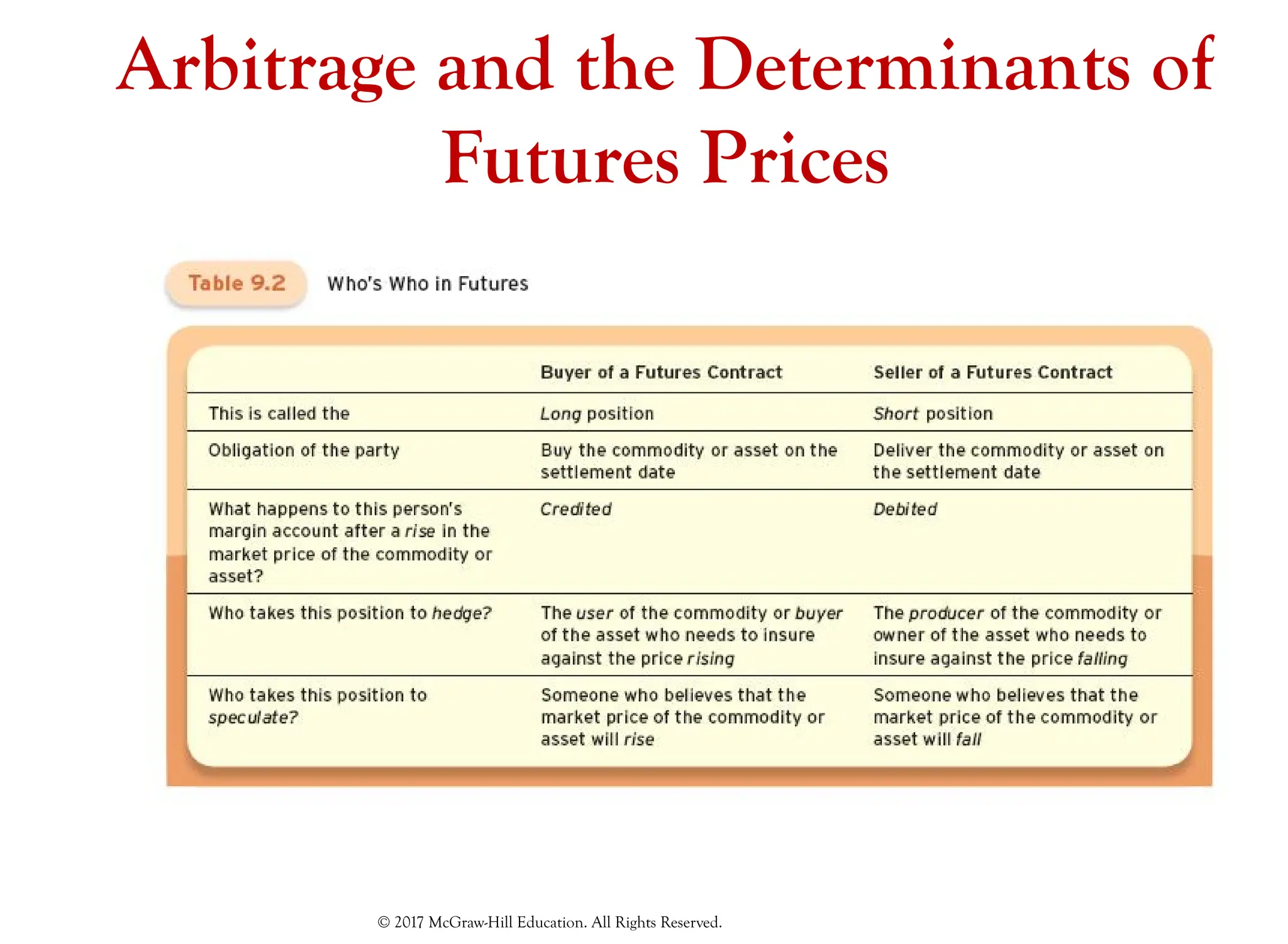

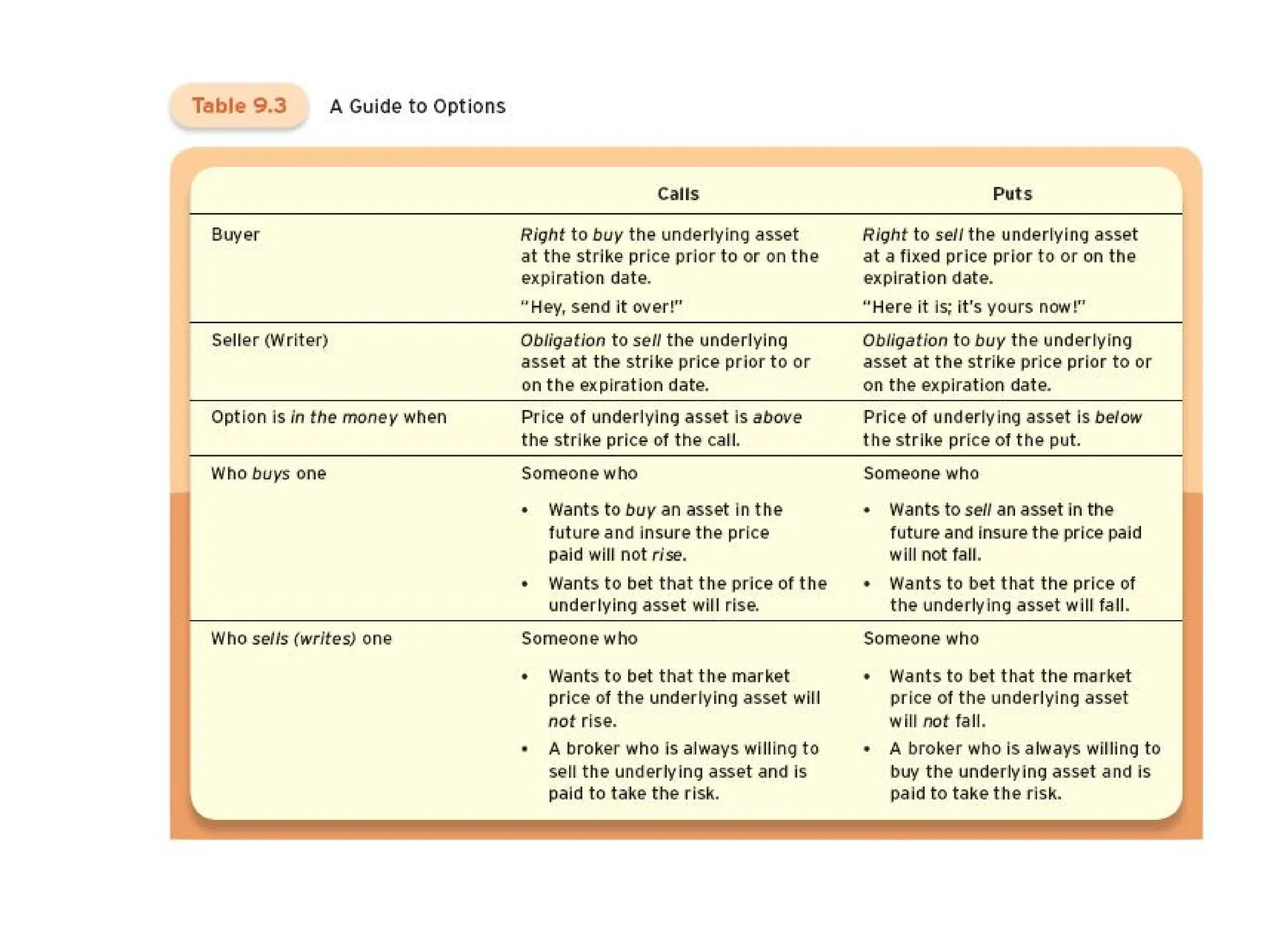

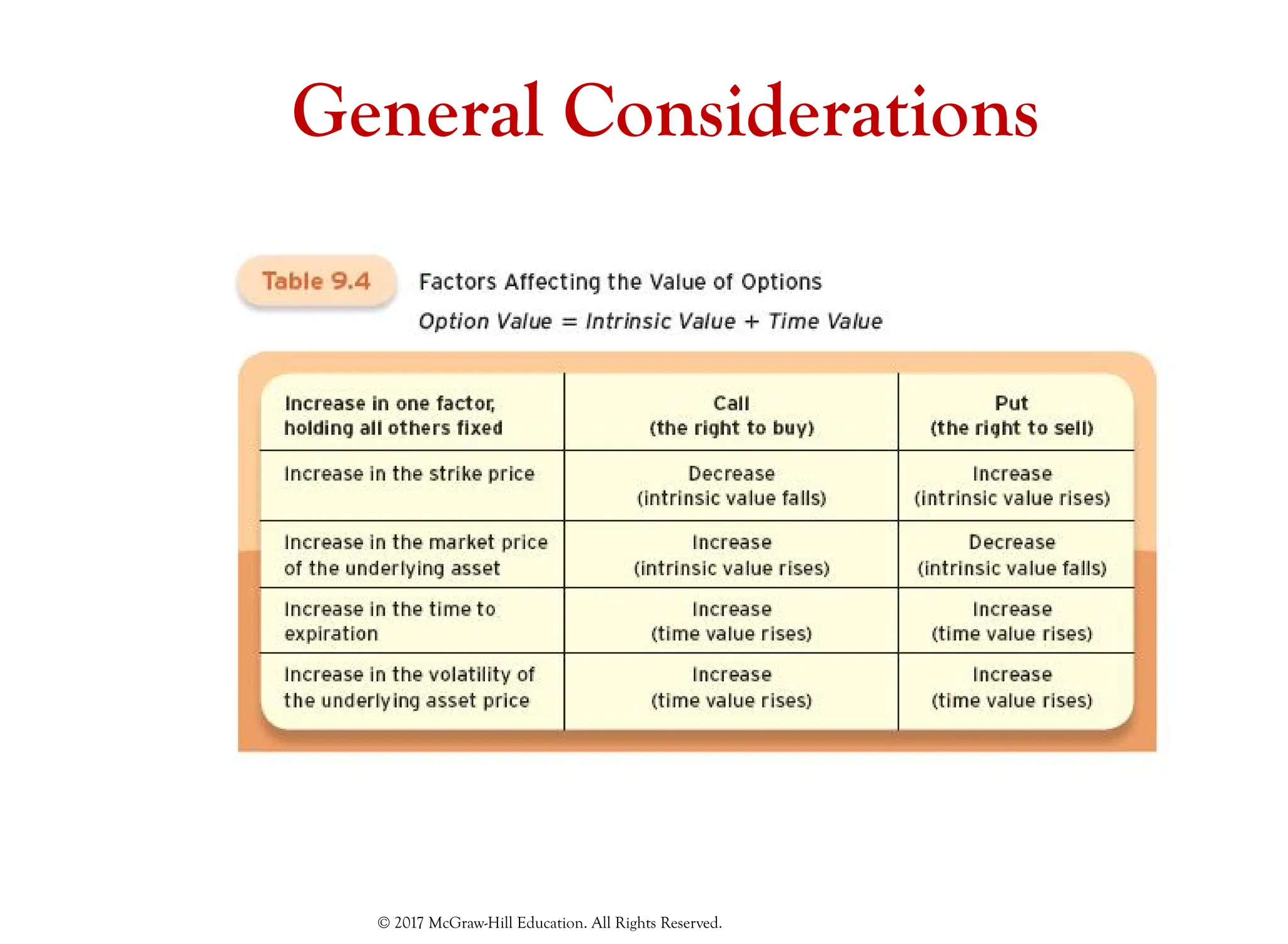

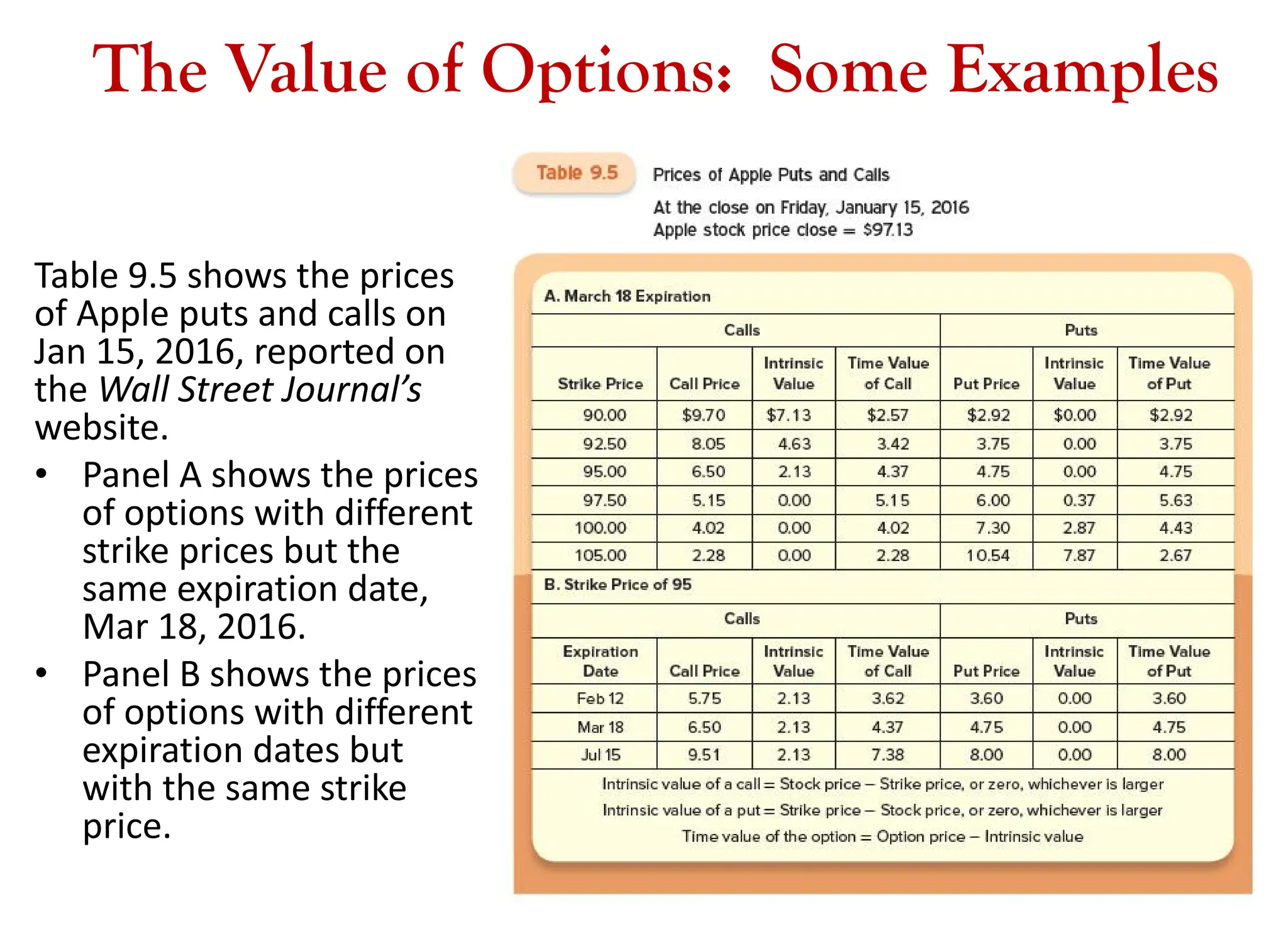

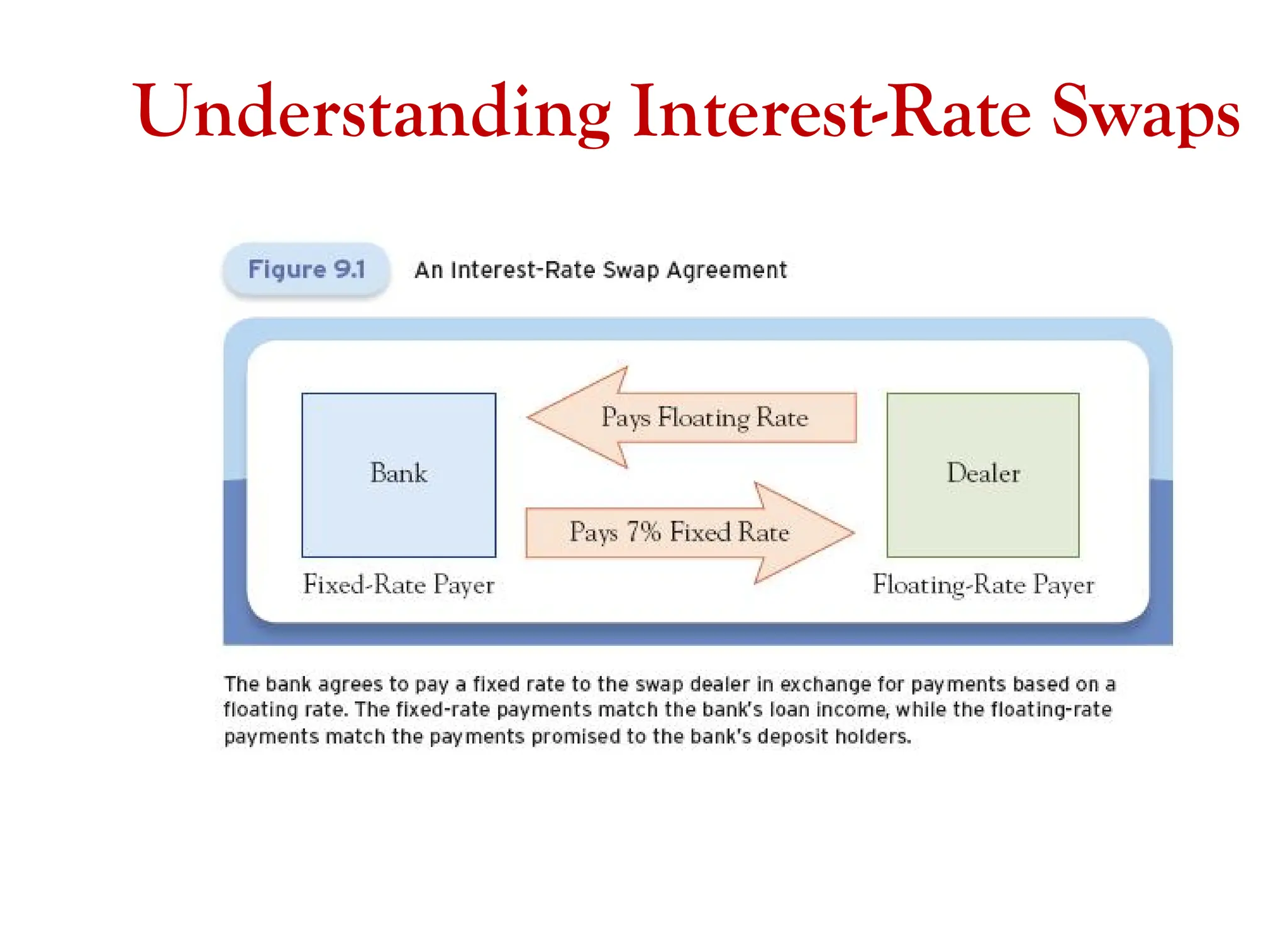

The document provides a comprehensive overview of derivatives, including futures, options, and swaps, detailing their definitions, purposes, and uses in transferring risk. It highlights the functionality of futures contracts in risk management, the mechanics of options for speculative purposes, and the role of swaps in financial transactions. The text emphasizes the importance of understanding these financial instruments to navigate their complexities and risks effectively.