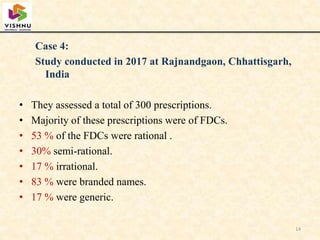

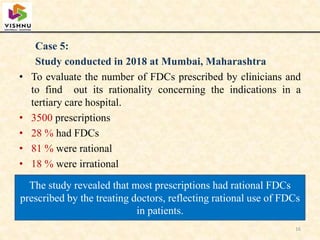

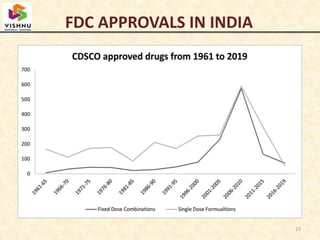

1) Fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) containing multiple active pharmaceutical ingredients are increasingly common in India but have faced regulatory issues.

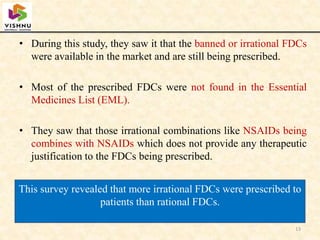

2) A parliamentary report found that many FDCs were approved by state authorities without clearance from the central drug regulator and recommended banning FDCs that could not prove safety and efficacy.

3) In 2016 and 2018, the central government banned over 300 FDCs citing lack of therapeutic justification after expert reviews, though the decisions were appealed by pharmaceutical companies.