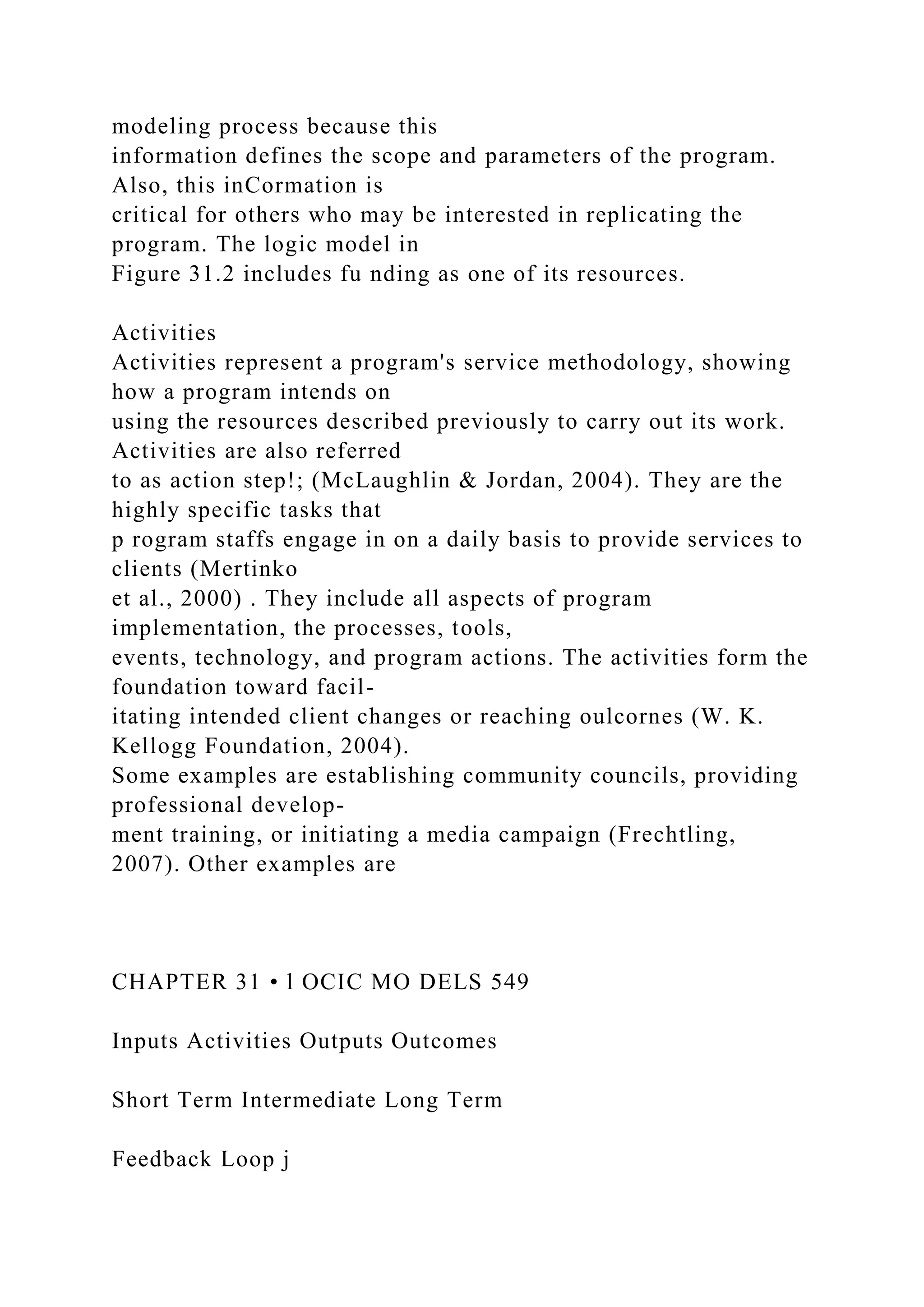

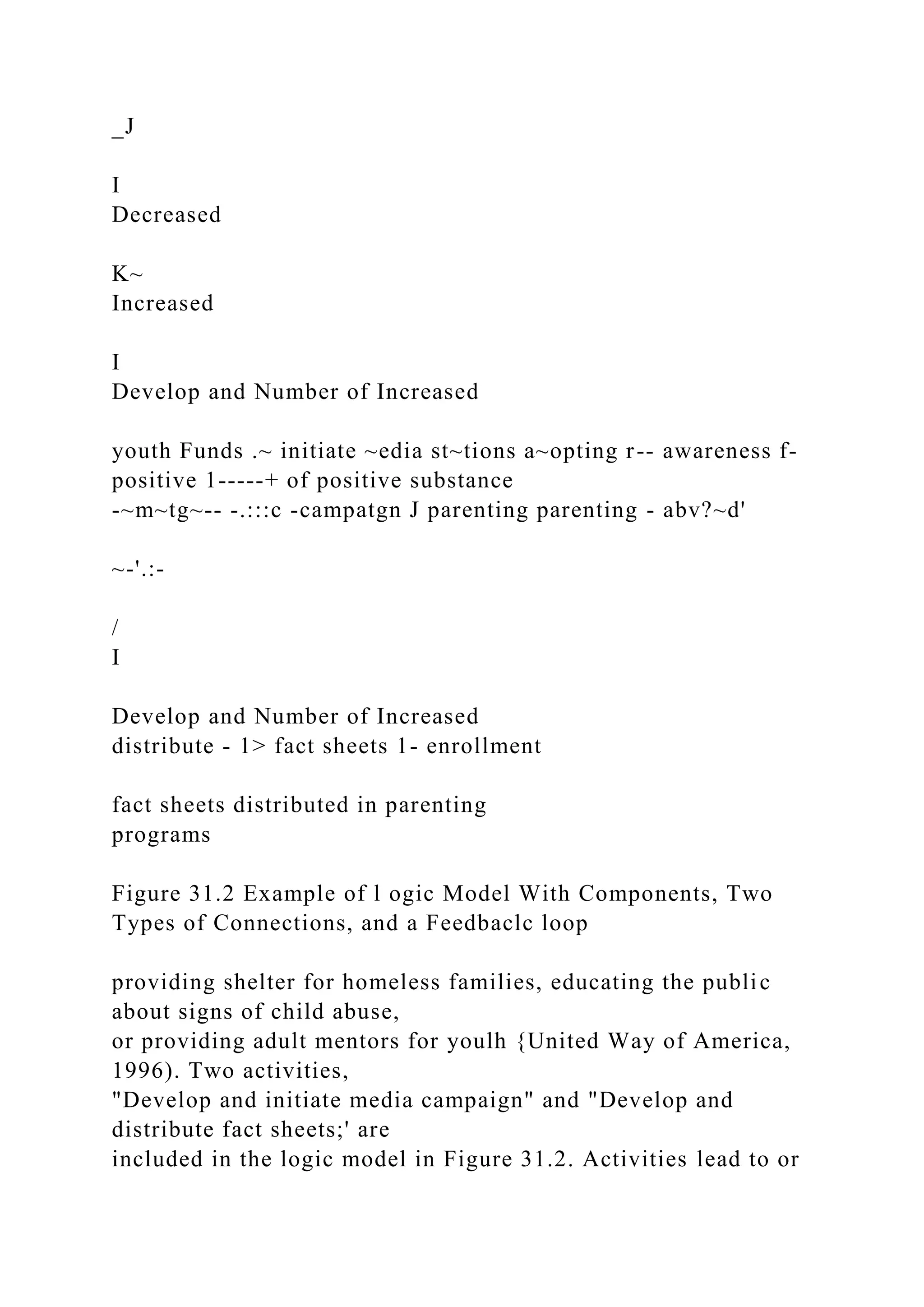

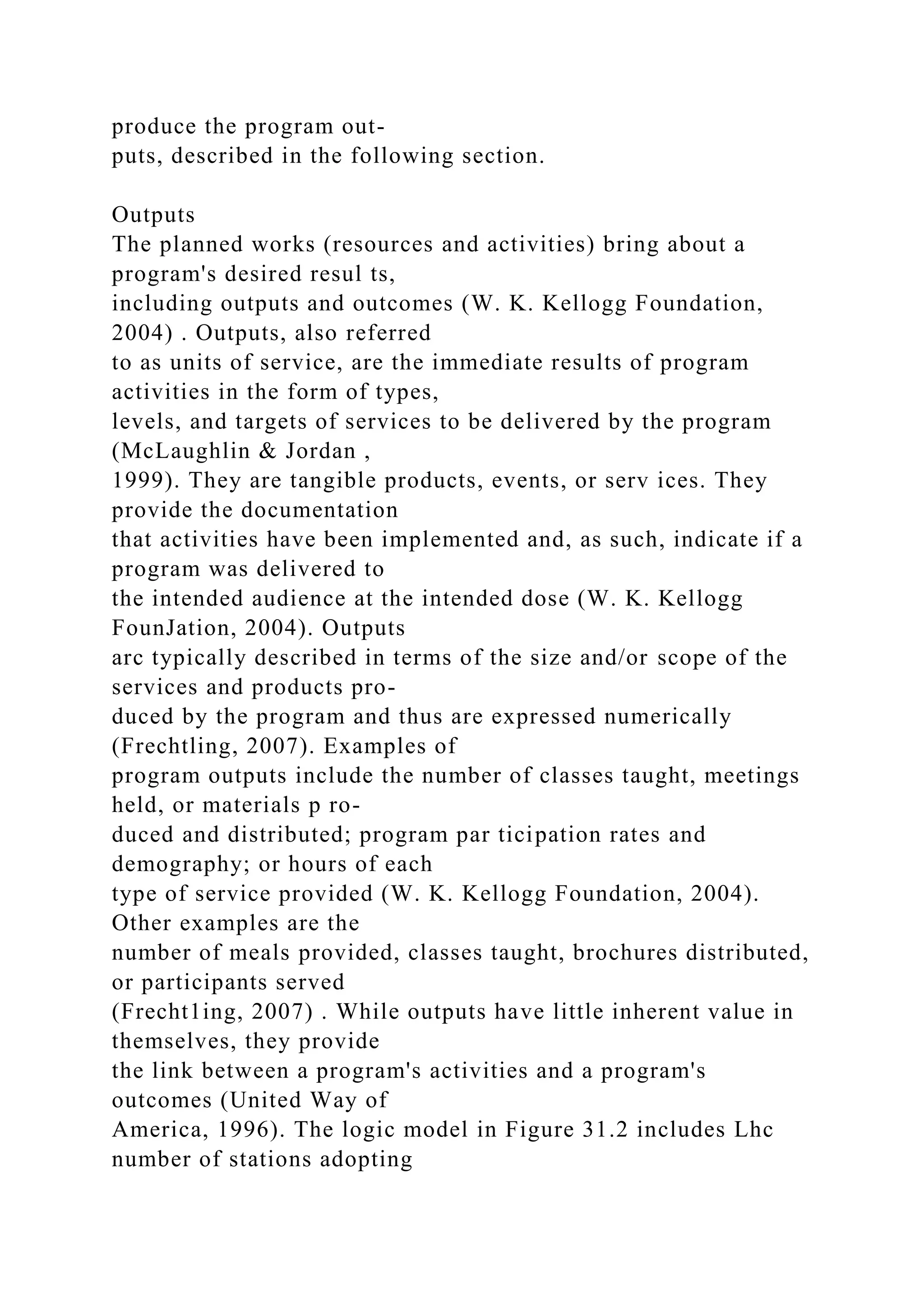

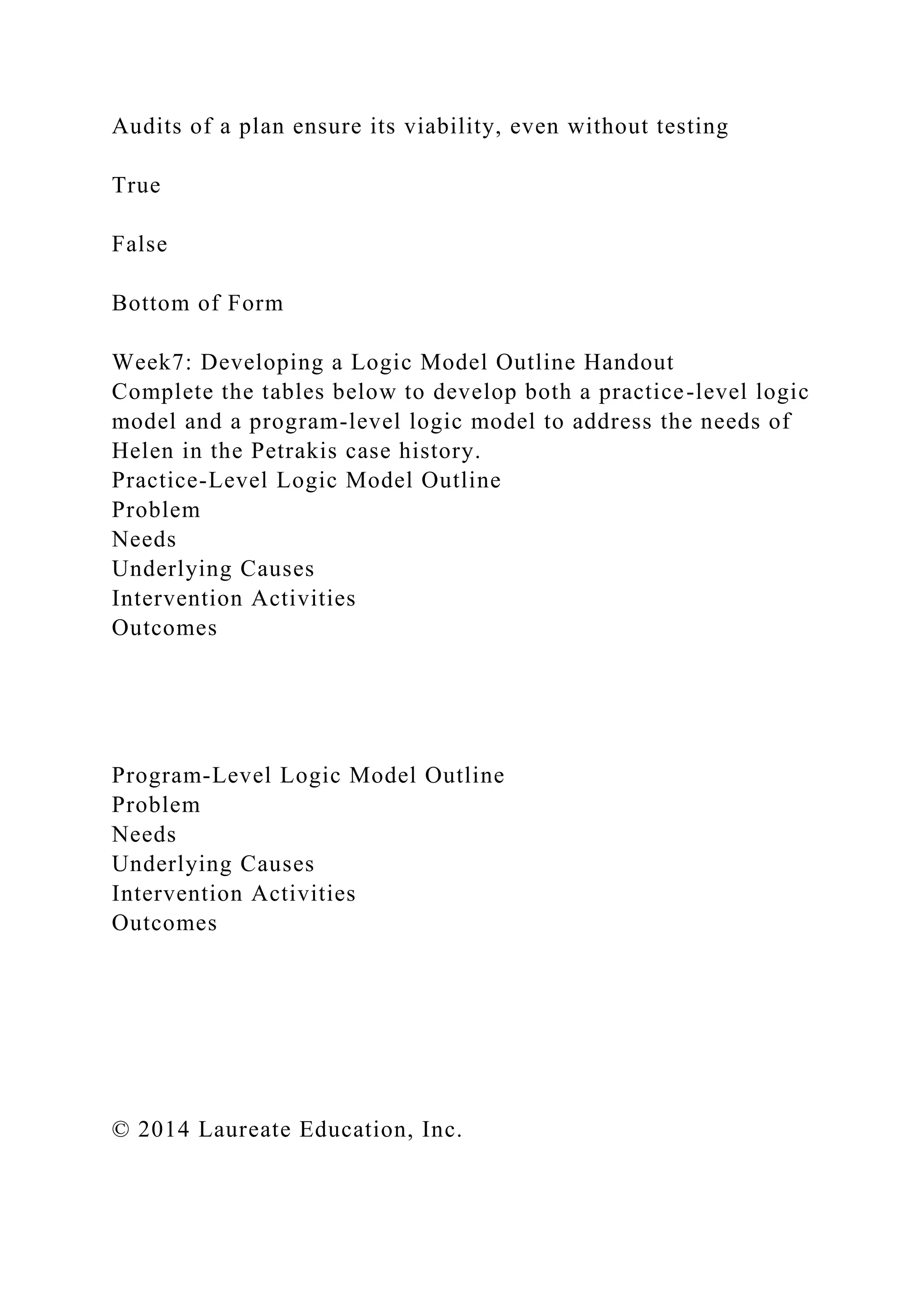

The document discusses logic models, which are diagrams that represent the relationships between program components such as inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes, guiding program evaluation and implementation. It emphasizes the importance of these models in illustrating causal relationships and the theory of change, while also addressing the components, types of outcomes, and connections between them. Additionally, it highlights the role of contextual factors in shaping program results and the relationship between these models and program theory.