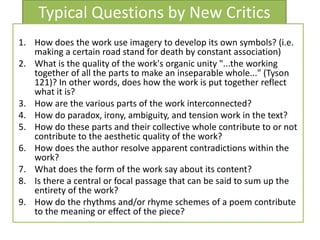

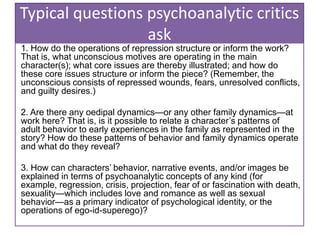

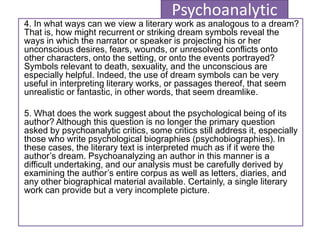

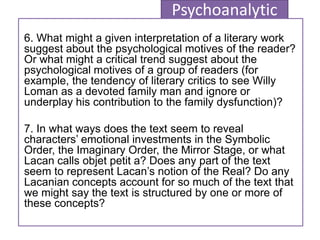

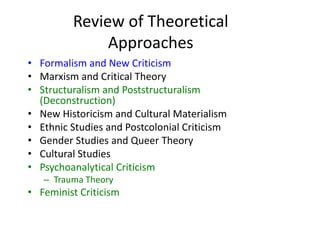

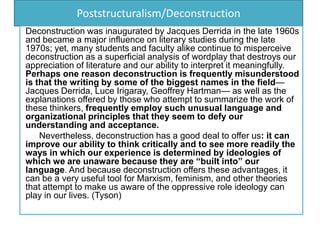

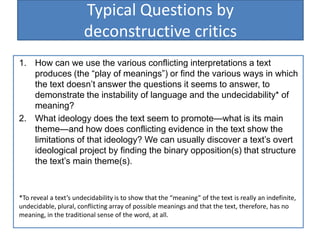

This document provides an agenda and overview of topics for a class on literary theory. It discusses several theoretical approaches including formalism, Marxism, structuralism, poststructuralism/deconstruction, new historicism, ethnic studies, gender studies, cultural studies, psychoanalytic criticism, and feminist criticism. For some of these approaches, it lists typical questions critics employing that approach may ask of a text. These include questions about symbols, themes, ideologies, social contexts, characters, and psychological elements in the works. It also covers key concepts and questions from deconstruction, feminist, psychoanalytic, and New Criticism approaches.

![Psychoanalytical Criticism

• If we take the time to understand some key concepts about

human experience offered by psychoanalysis, we can begin

to see the ways in which these concepts operate in our daily

lives in profound rather than superficial ways, and we’ll begin

to understand human behaviors that until now may have

seemed utterly baffling. And, of course, if psychoanalysis

can help us better understand human behavior, then it

must certainly be able to help us understand literary

texts, which are about human behavior. The concepts we’ll

discuss are based [largely] on the psychoanalytic principles

established by Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), whose theory of

the psyche often is referred to today as classical

psychoanalysis. We must remember that Freud evolved his

ideas over a long period of time, and many of his ideas

changed as he developed them. In addition, much of his

thinking was, as he pointed out, speculative, and he hoped

that others would continue to develop and even correct

certain of his ideas over time. (Tyson 12)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ewrt1cclass4-140409195311-phpapp01/85/Ewrt-1-c-class-4-11-320.jpg)