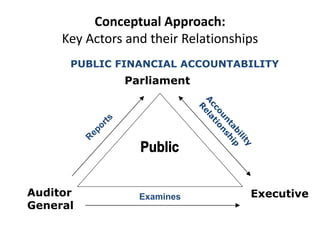

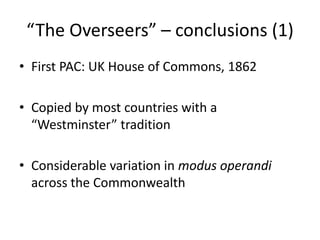

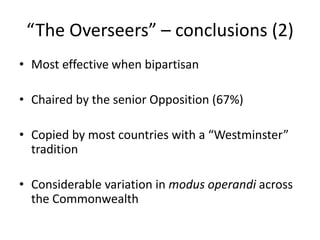

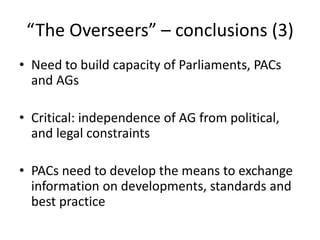

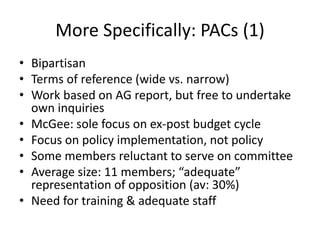

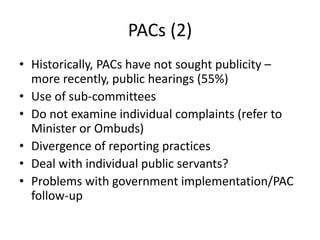

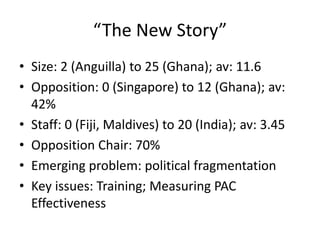

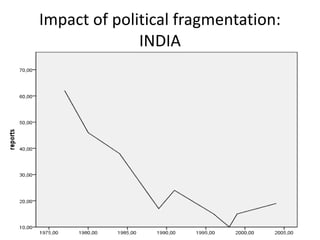

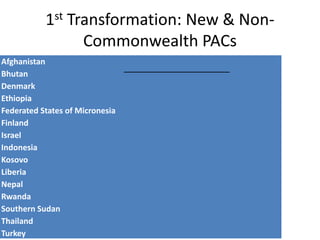

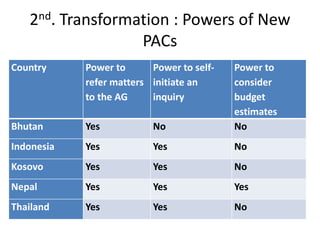

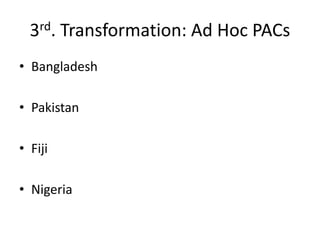

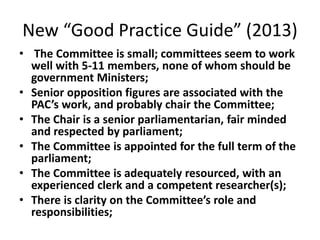

This document summarizes the evolution of best practices for public accounts committees (PACs) based on various studies conducted between 1999-2013. It outlines the traditional Westminster model of PACs and how they have transformed in new and non-Commonwealth countries. PACs are increasingly taking on powers like self-initiating inquiries and considering budget estimates. The document concludes with recommendations for good practices like adequate resources, open hearings, follow up on recommendations, and specialized training for PAC members.