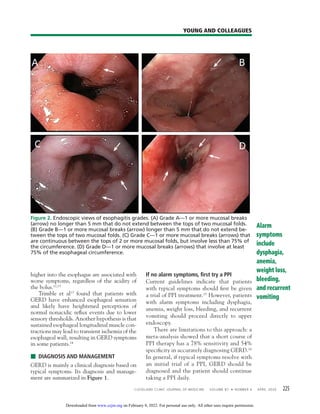

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common condition affecting up to 20% of adults in Western countries. It is mainly diagnosed clinically based on symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the first-line treatment and most patients should try PPI therapy for 8 weeks initially. If symptoms do not resolve, endoscopy may be considered to check for complications. Lifestyle modifications such as weight loss and sleep positioning changes can also help manage GERD symptoms.