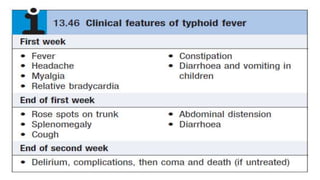

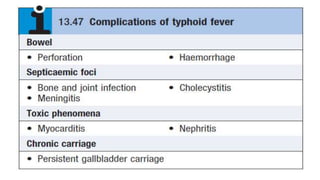

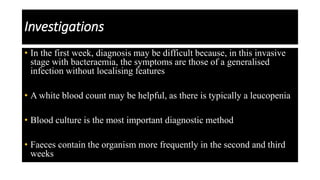

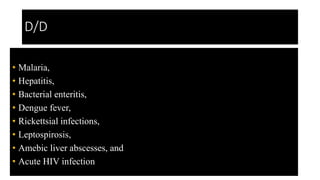

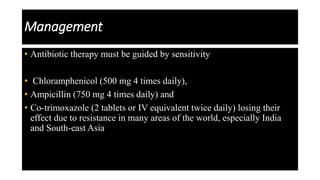

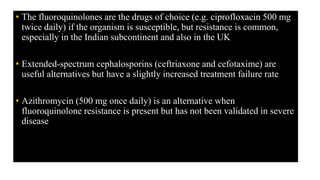

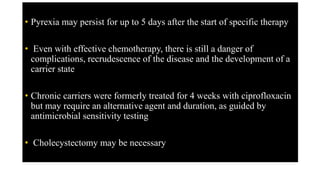

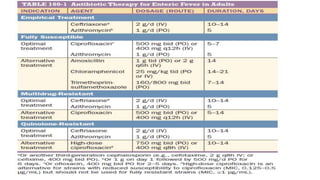

Enteric (typhoid) fever is caused by Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi bacteria, transmitted through contaminated food or water. It causes systemic infection characterized by fever and abdominal symptoms. If left untreated, it can lead to severe complications involving multiple organ systems. Diagnosis involves blood culture early and stool culture later. Treatment requires antibiotics like fluoroquinolones or cephalosporins for at least 10 days. Prevention involves vaccination and improved sanitation.