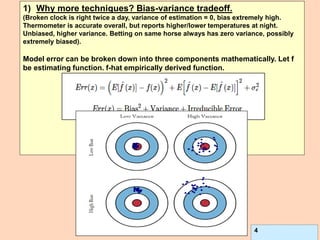

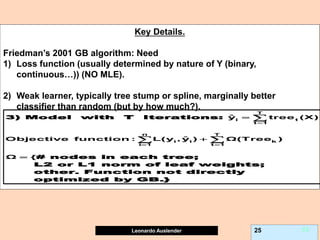

Gradient boosting is an ensemble technique that combines weak learners, such as decision trees, into a single strong learner. It works by iteratively fitting a prediction model to the negative gradient of the loss function, which represents the residuals or errors from the previous iteration. This process of residual fitting helps reduce bias and variance in the model. Gradient boosting has advantages over other techniques like bagging in that it can reduce both bias and variance through its iterative process, while avoiding overfitting by using weak learners and a regularization parameter.

![Leonardo Auslender Copyright 2004

Leonardo Auslender 26 26

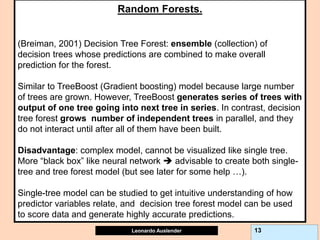

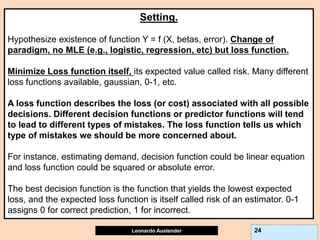

L2-error penalizes symmetrically away from 0, Huber penalizes less than OLS

away from [-1, 1], Bernoulli and Adaboost are very similar. Note that Y ε [-1, 1]

in 0-1 case here.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ensembles-220919142158-3c64bd97/85/Ensembles-pdf-26-320.jpg)

![Leonardo Auslender Copyright 2004

Leonardo Auslender 39 39

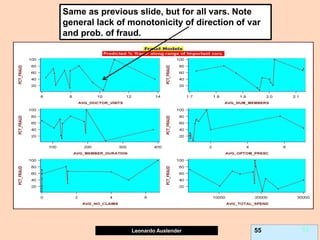

Partial Dependence plots (PDP).

Due to GB (and other methods’) black-box nature, PDPs show effect of predictor X on

fitted modeled response (notice, NOT ‘true’ model values) once all other predictors

have been marginalized (integrated away). Marginalized Predictors usually fixed at

constant value, such as mean. Graphs may not capture nature of variable interactions

especially if interaction significantly affect model outcome.

Assume Y = f (X) = f (Xa, Xb), where X = Xa U Xb, Xa subset of predictors of interest. PDP

displays the marginal expected value of f (Xa), by averaging over values of Xb (and

assuming Xa to be single predictor), given by f(Xa = xa, Avg (Xbi))) where the average of

the function for a given value (vector) of the subset Xa is the average value of the model

output setting the Xa to value of interest and averaging the result with the values of Xb as

they exist in the data set. Formally:

Since GB, Boosting, Bagging, etc are BLACK BOX models, use PDP to obtain model

interpretation. Also useful for logistic models.

b

b

b b

X a b a b b

X

a a a b

x X

b

E [f(X , X )] f(X , X )dP(X ),

P : unknown density. Integral estimated by :

1

PDP(X x ) f(x , x )

| X |

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ensembles-220919142158-3c64bd97/85/Ensembles-pdf-39-320.jpg)

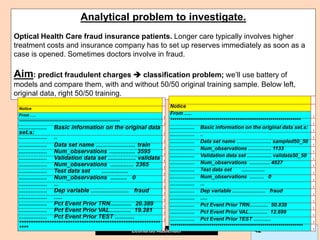

![Leonardo Auslender Copyright 2004

Leonardo Auslender 97 97

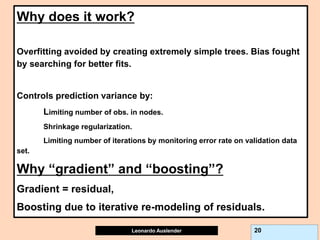

General Comments II.

5) While on classification GB problems, predictions are within [0, 1], for

continuous target problems, predictions can be beyond the range of the

target variable headaches. I.e., negative predictions for target > 0.

This is due to the fact that GB models residuals at each iteration, not the

original target; this can lead to surprises, such as negative predictions

when Y takes only non-negative values, contrary to the original Tree

algorithm.

6) GB Shrinkage parameter and early stopping (# trees) act as

regularizers but combined effect not known and could be ineffective.

7) If GB shrinkage too small, and allow large Tree, model is large,

expensive to compute, implement and understand.

8) Financial Information not easily ranked. Ranking models according to

financials not equivalent to rankings by fraud detection (i.e., cum lift).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ensembles-220919142158-3c64bd97/85/Ensembles-pdf-97-320.jpg)