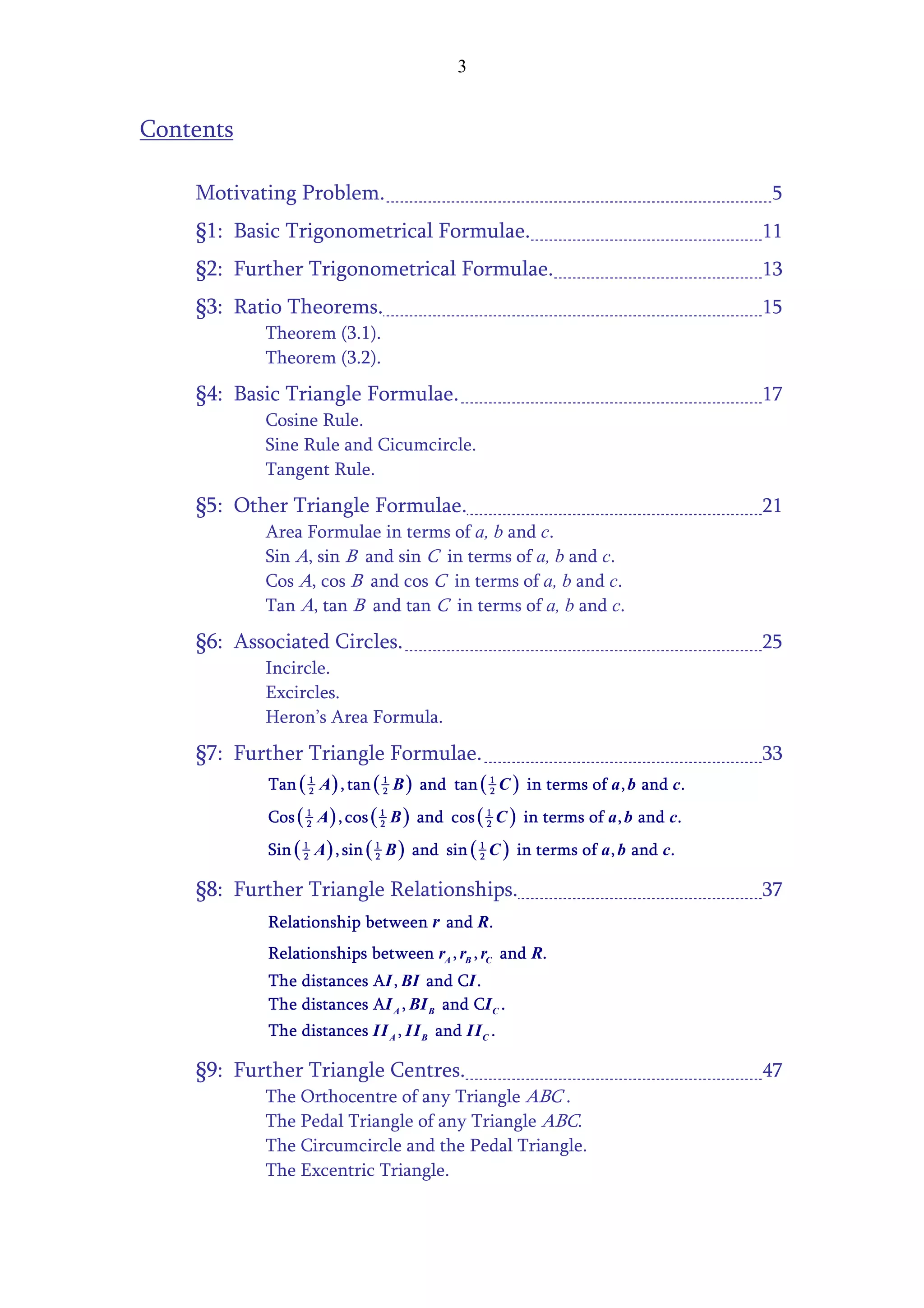

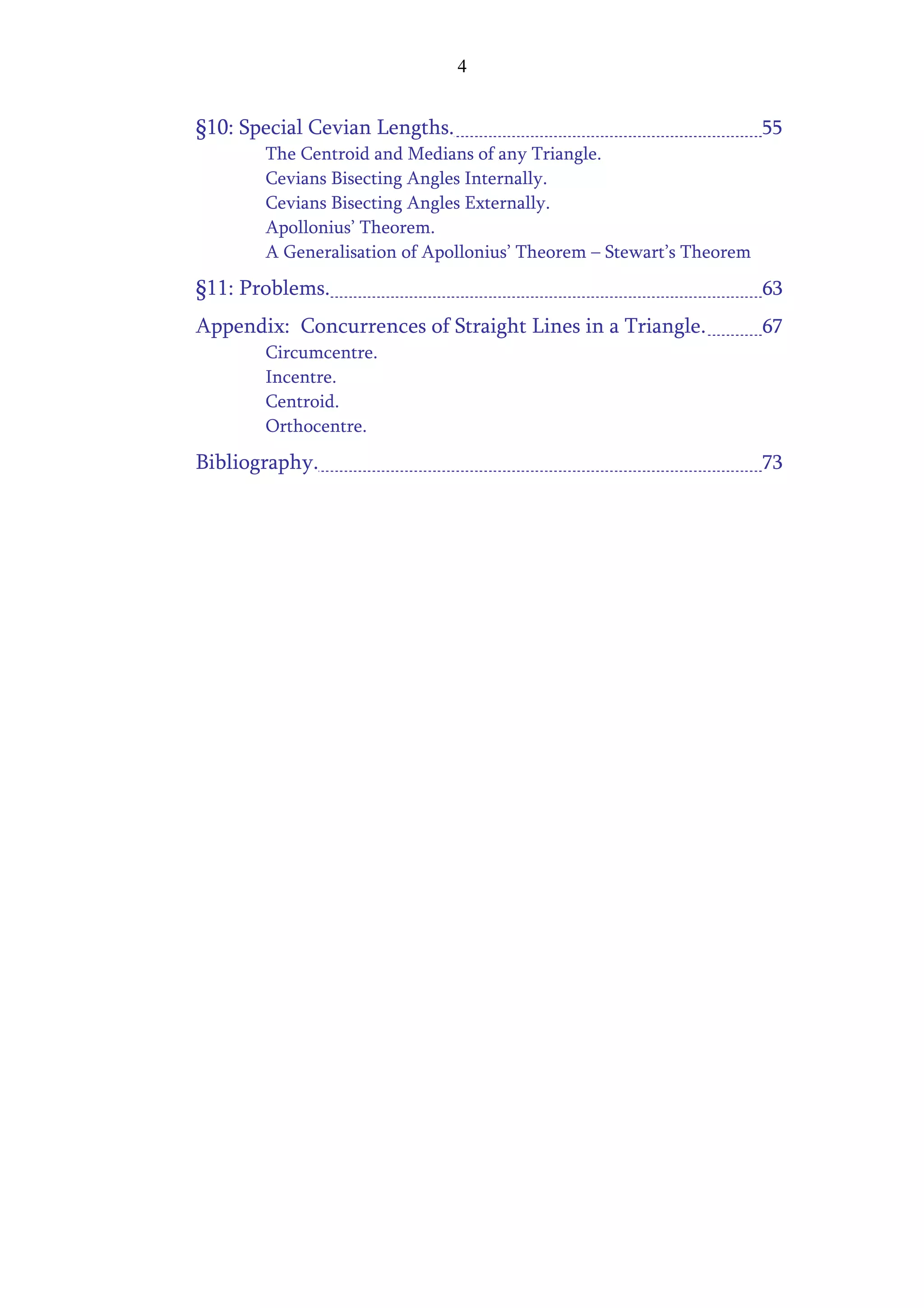

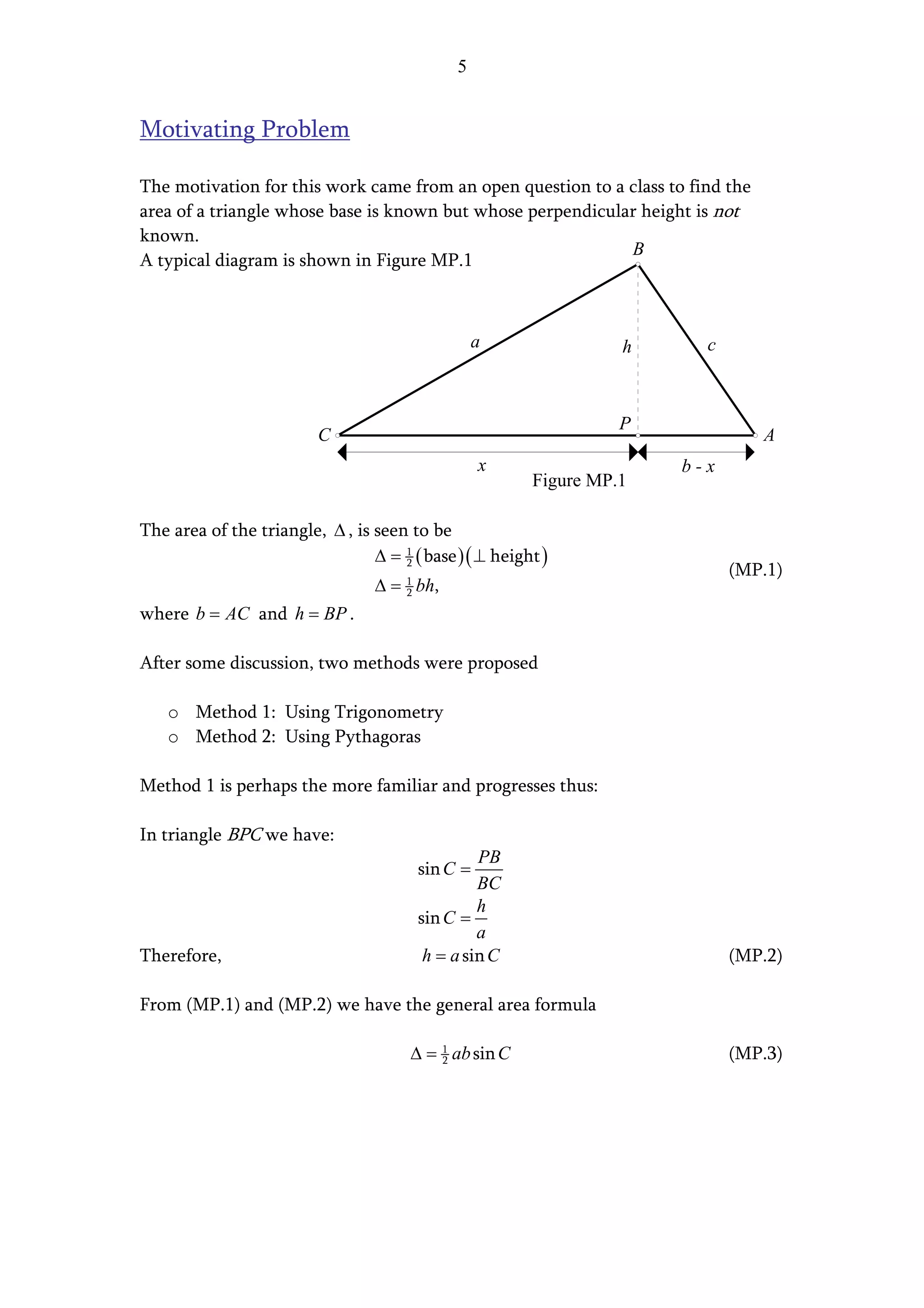

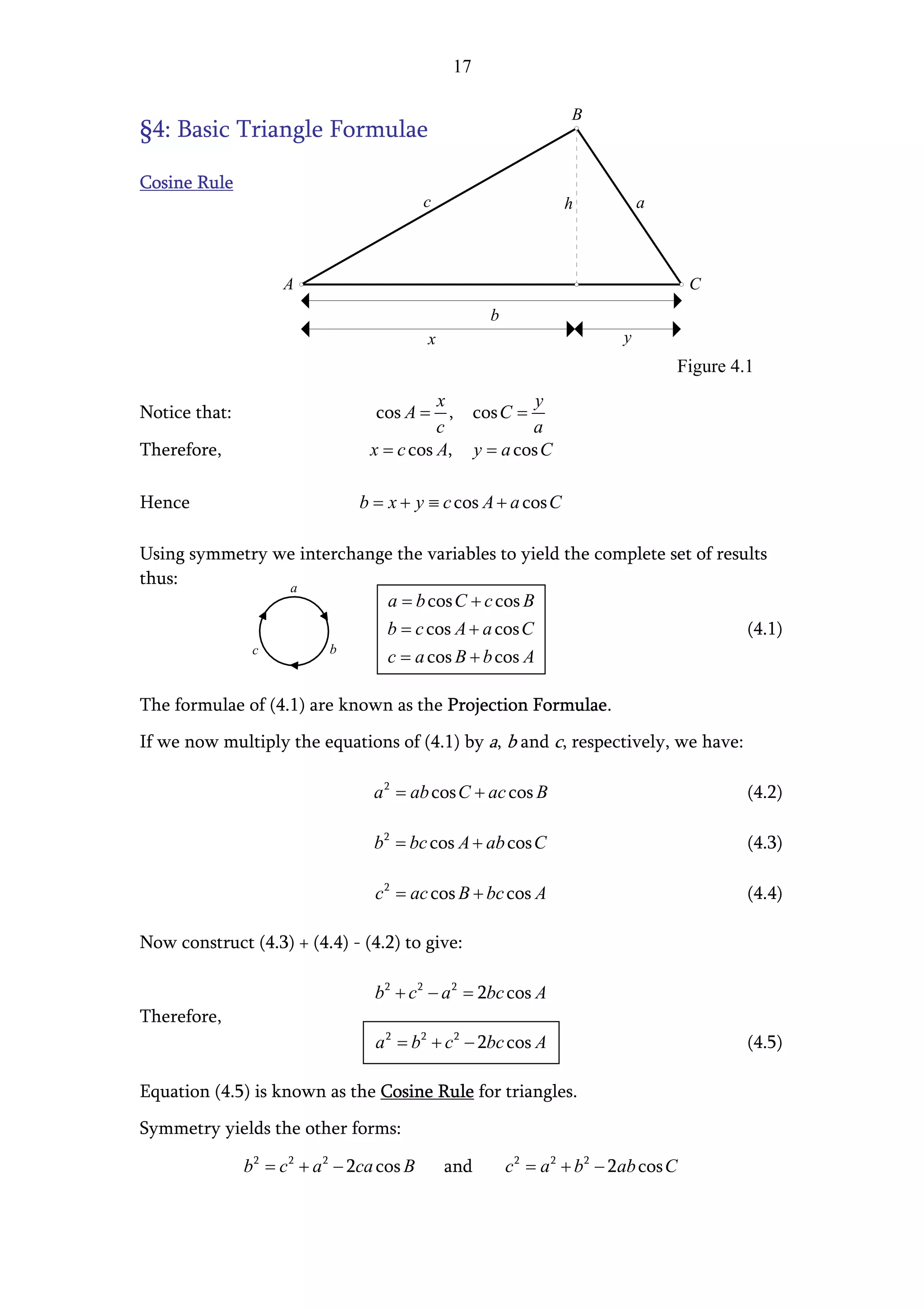

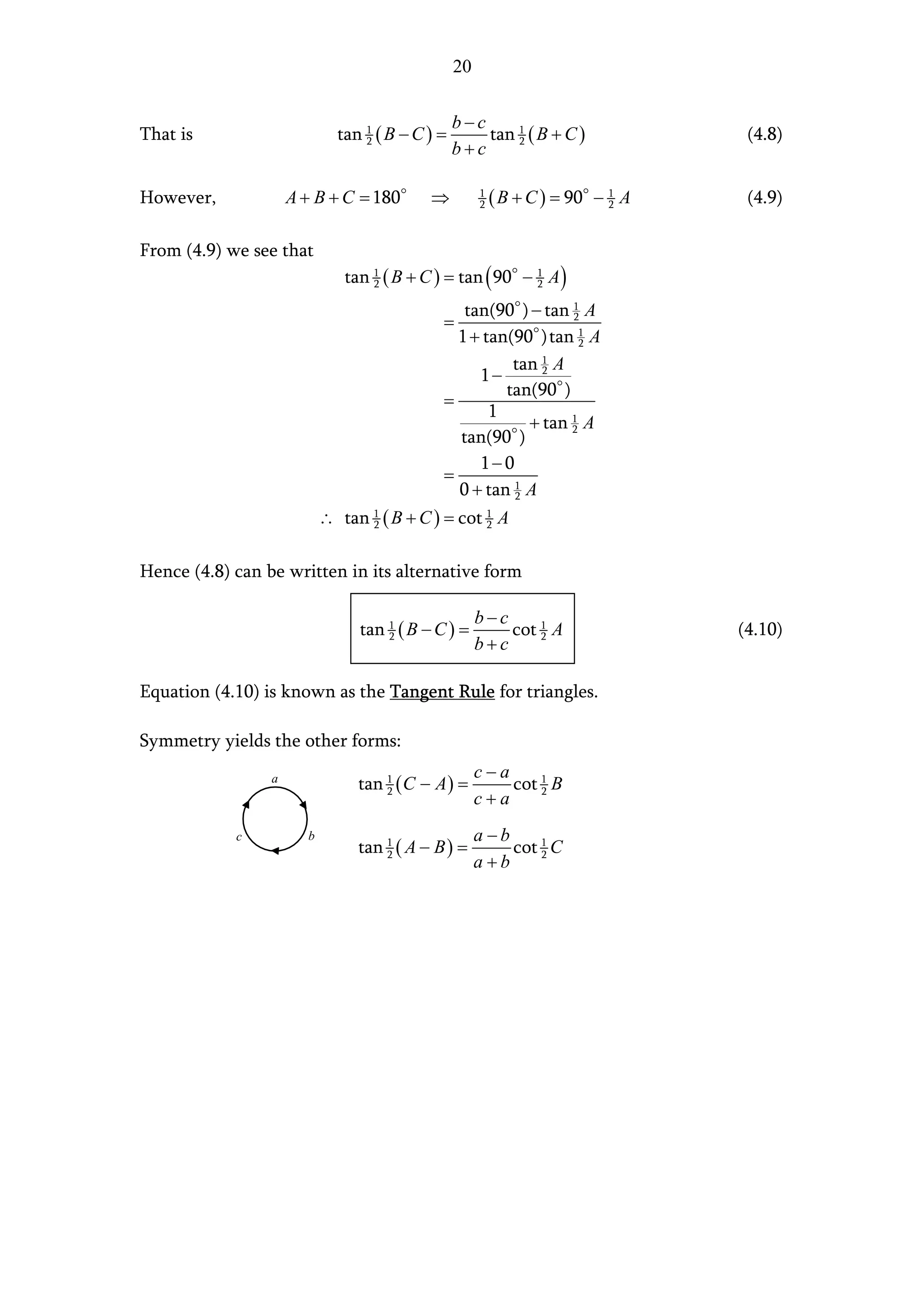

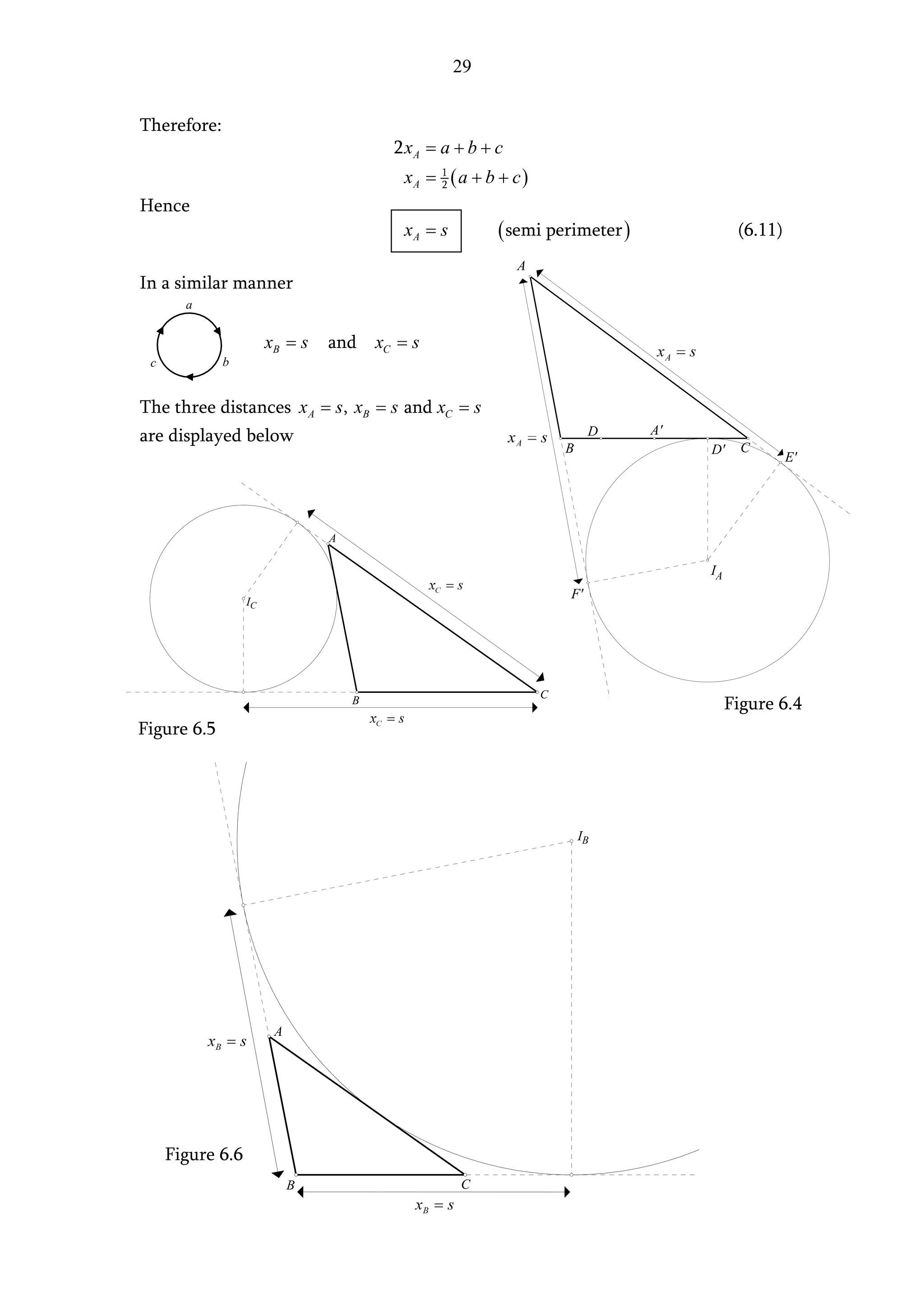

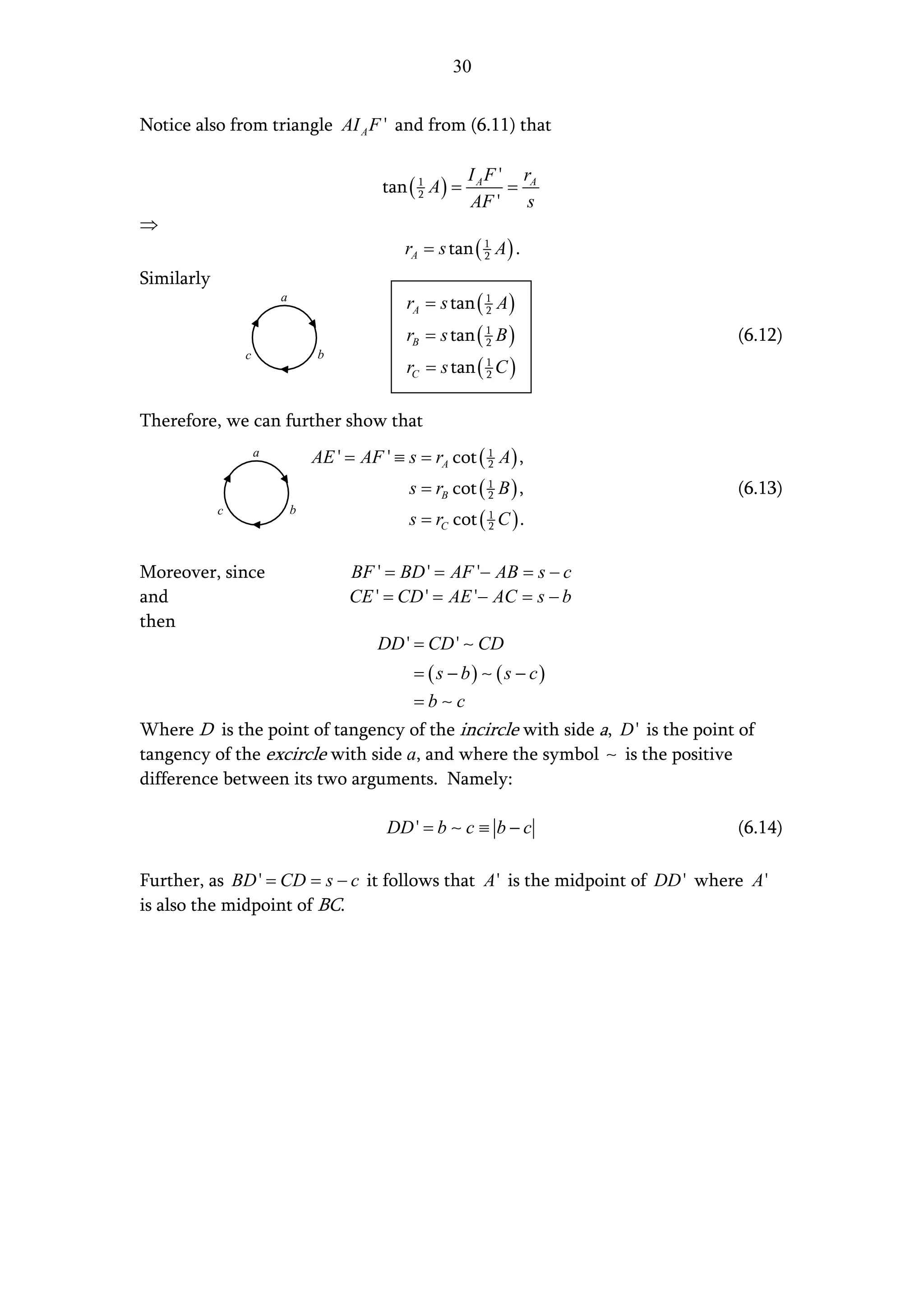

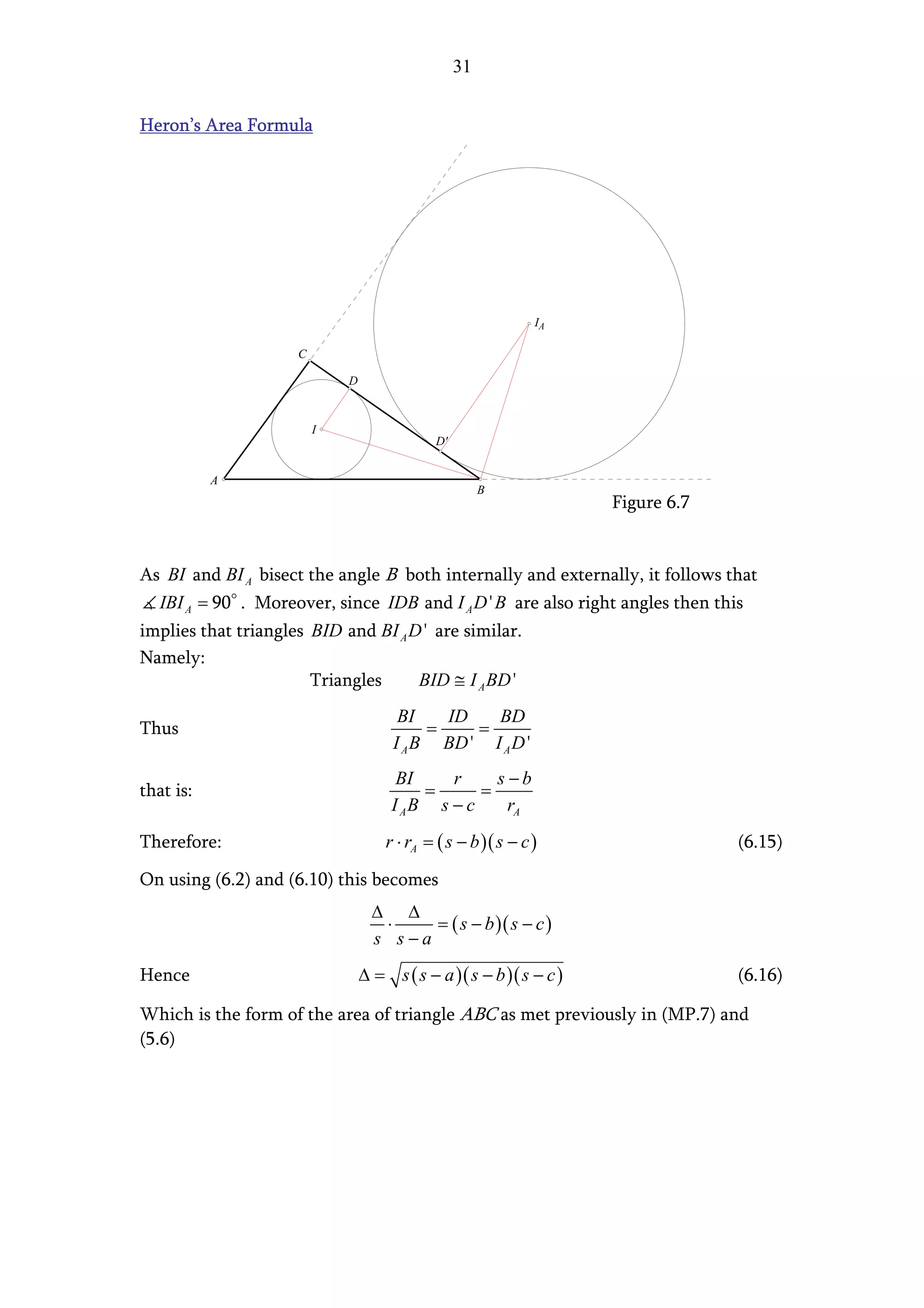

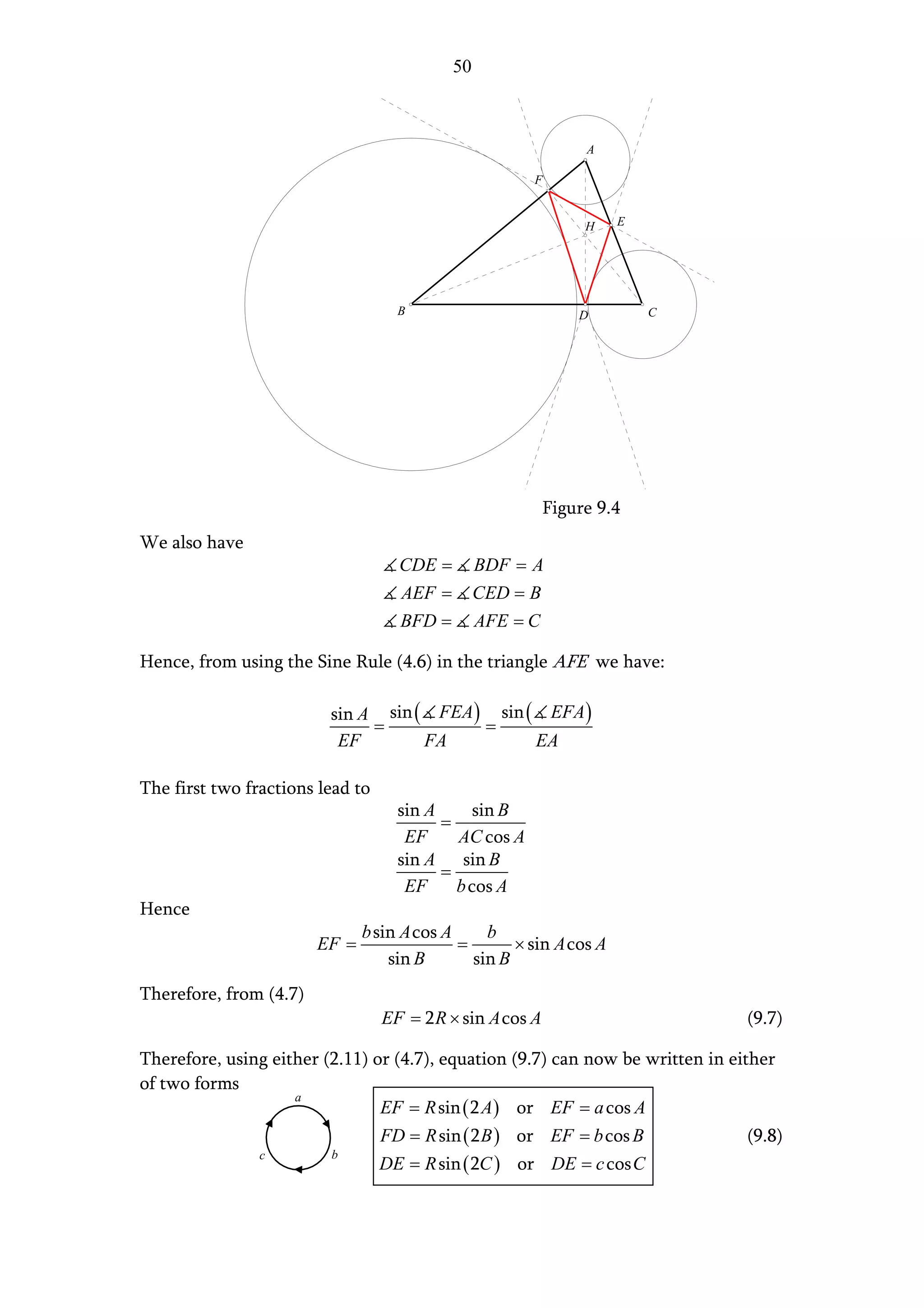

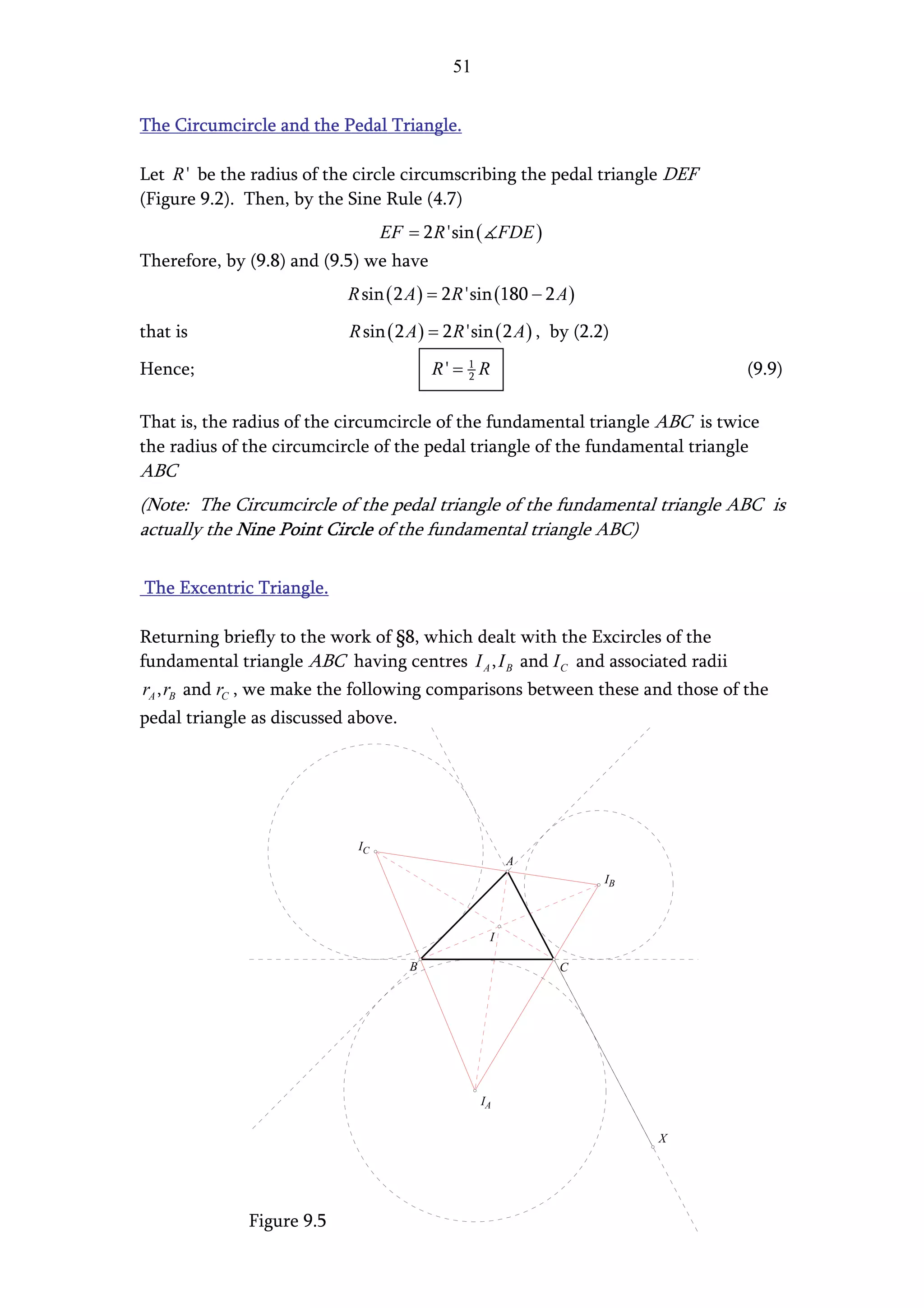

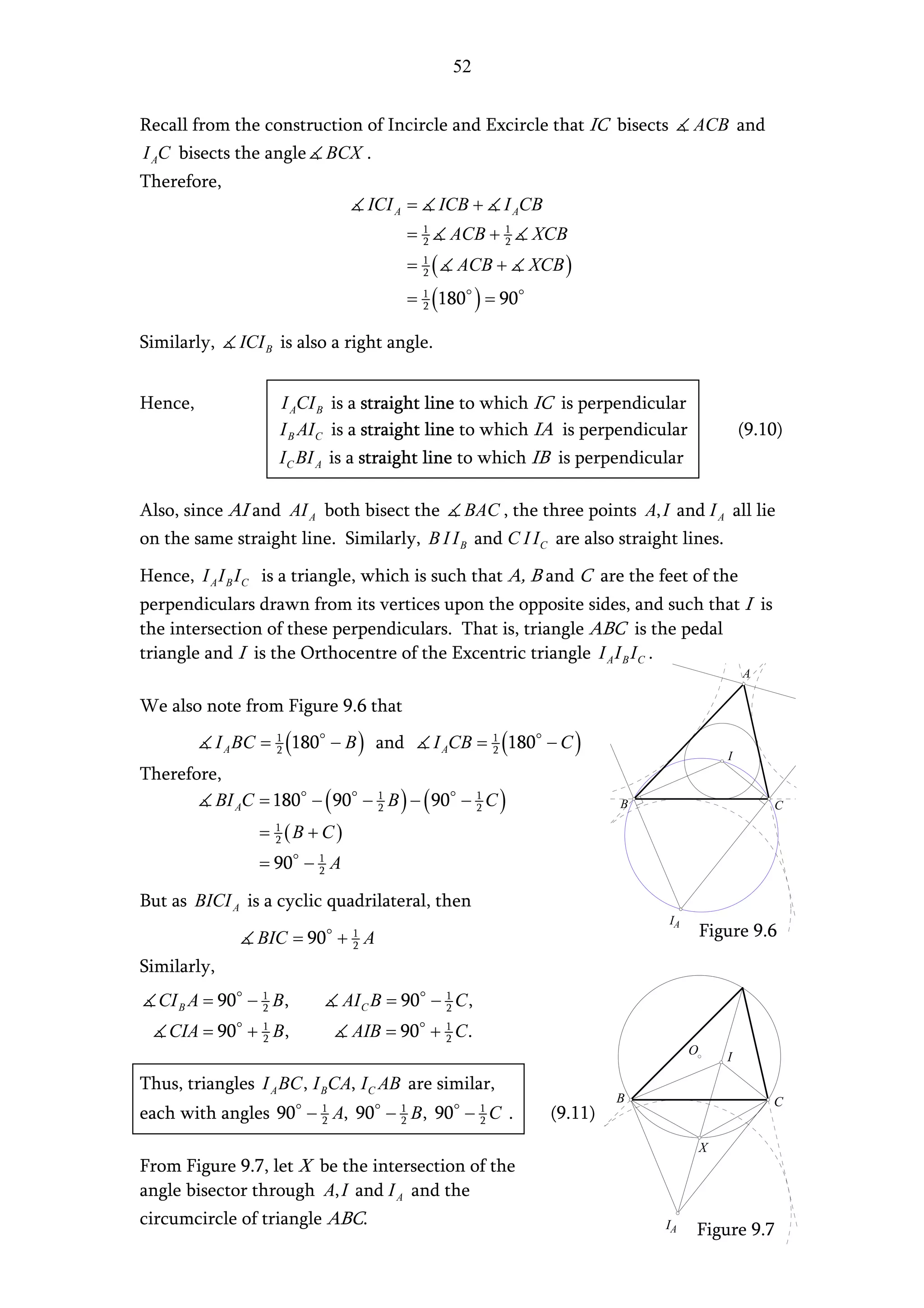

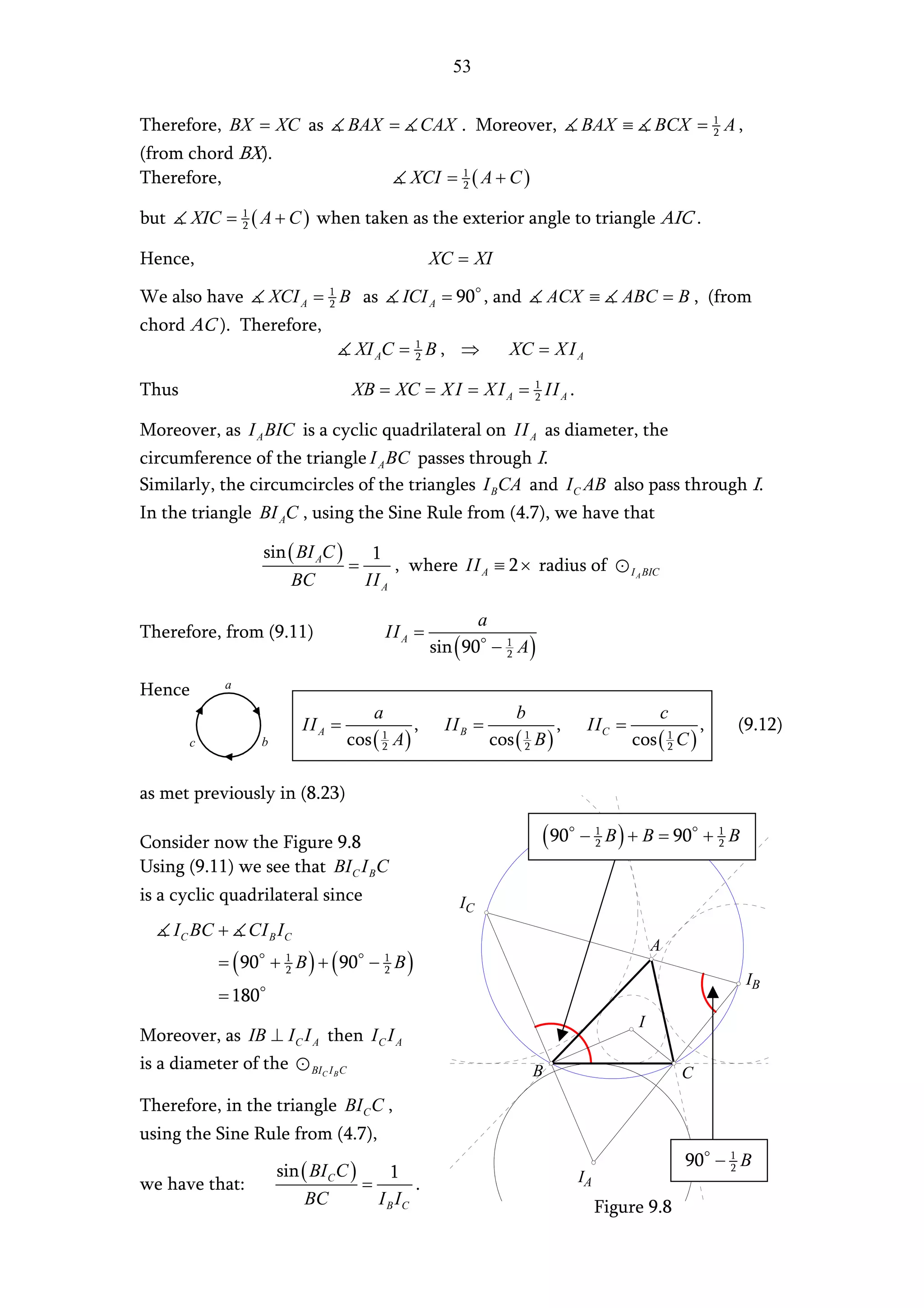

The document presents two methods for finding the area of a triangle when the base is known but the perpendicular height is not:

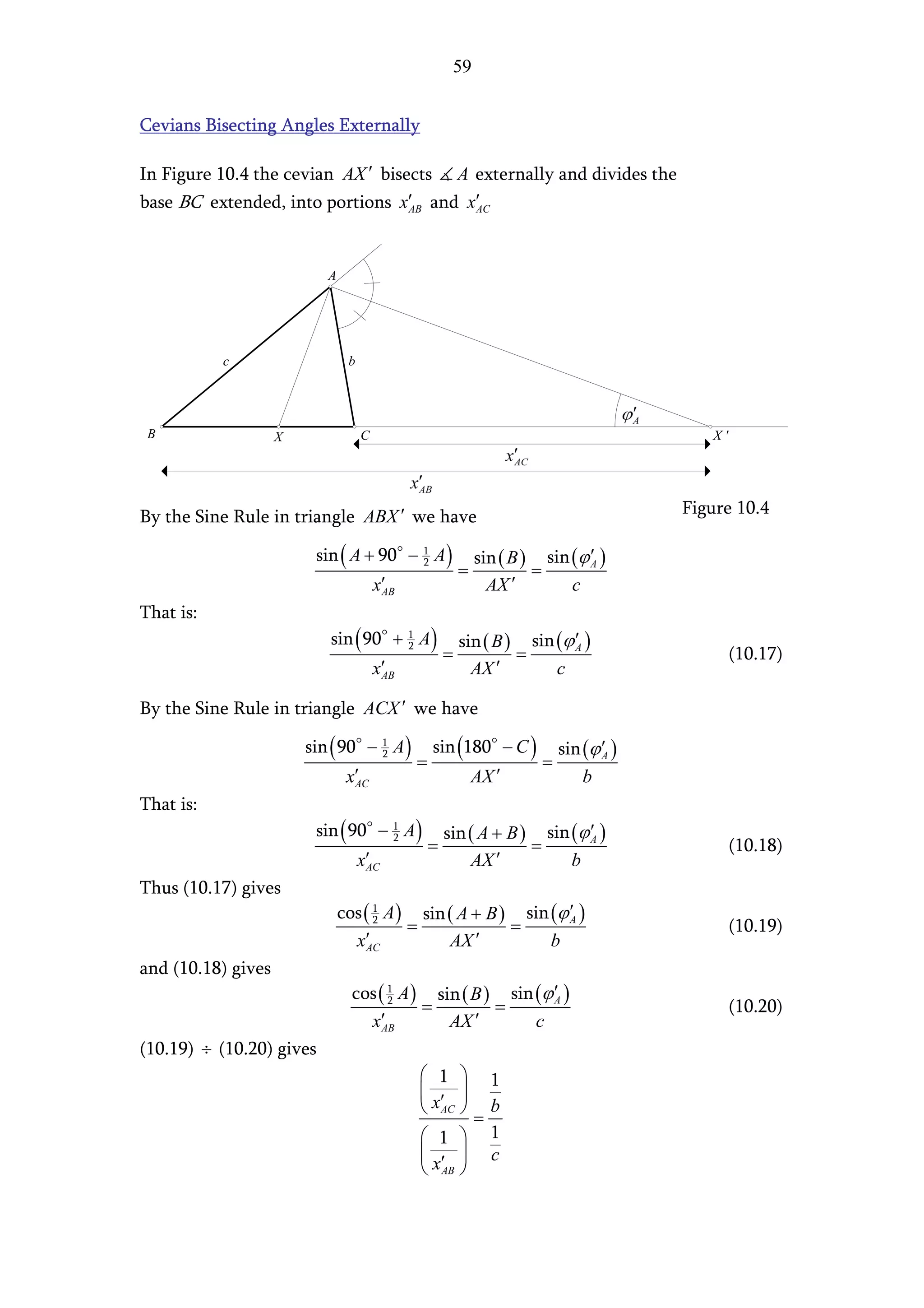

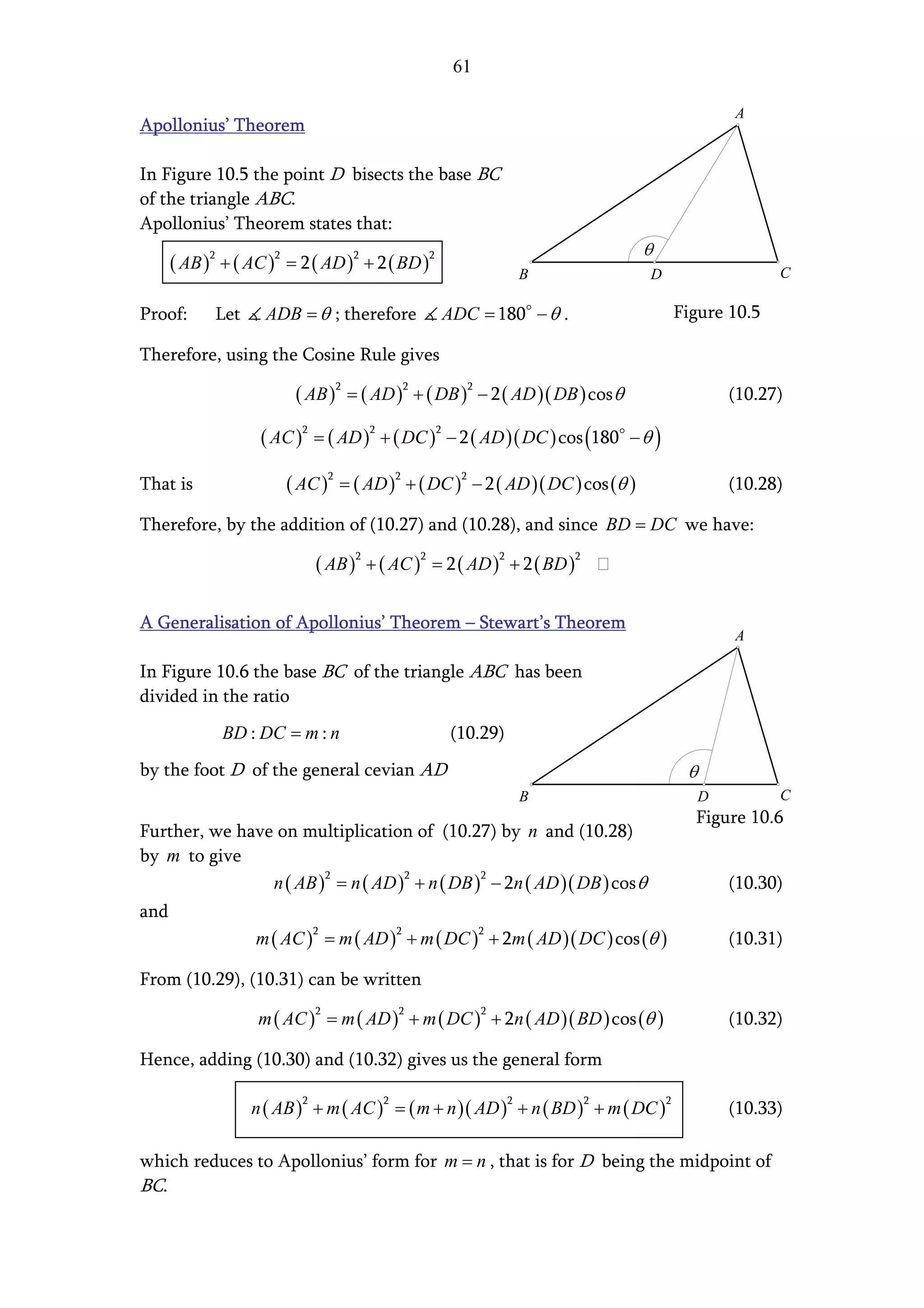

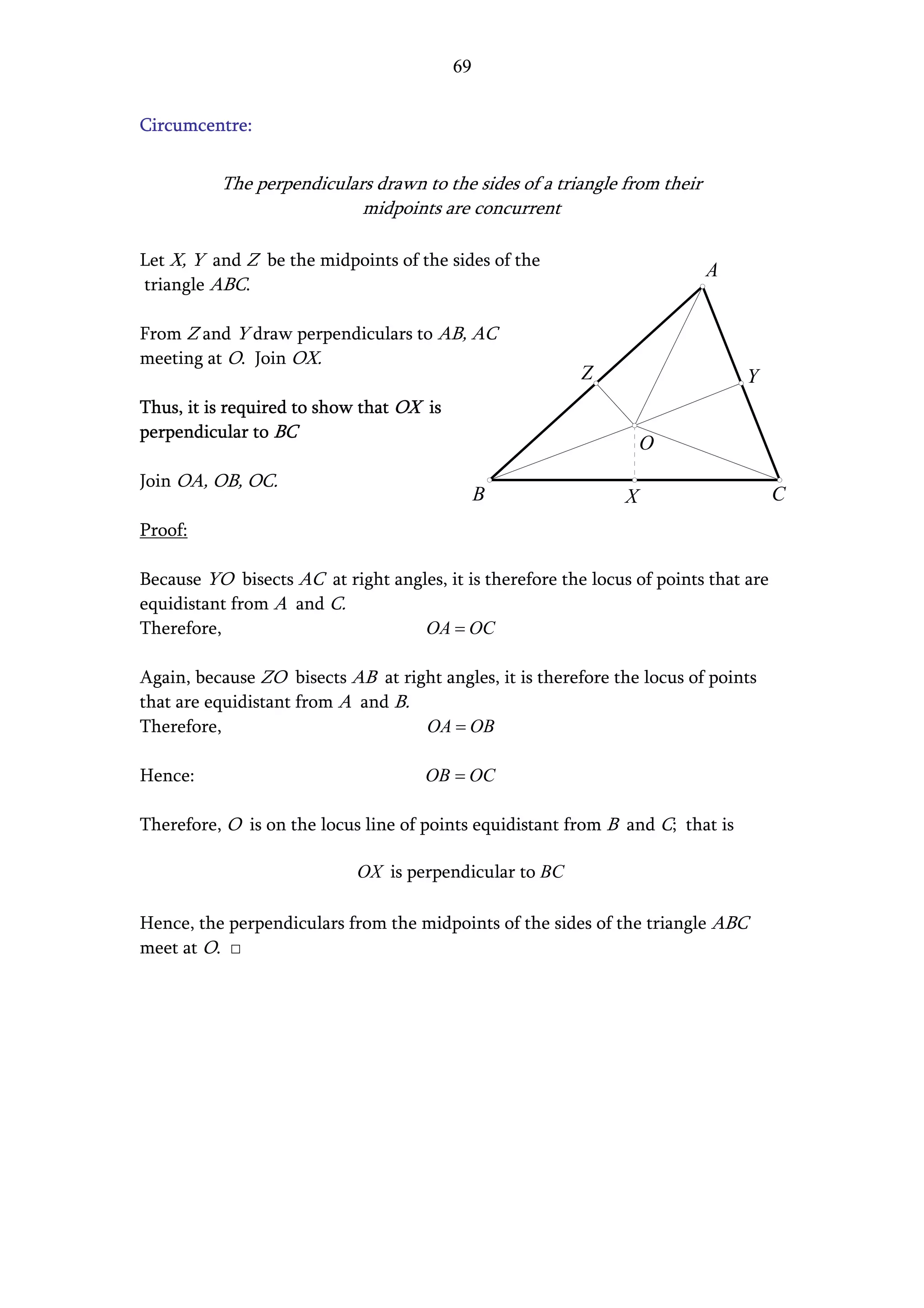

1. Using trigonometry, it derives an expression for the height in terms of one of the angles and the base, leading to the general area formula involving the base, one side, and an opposite angle.

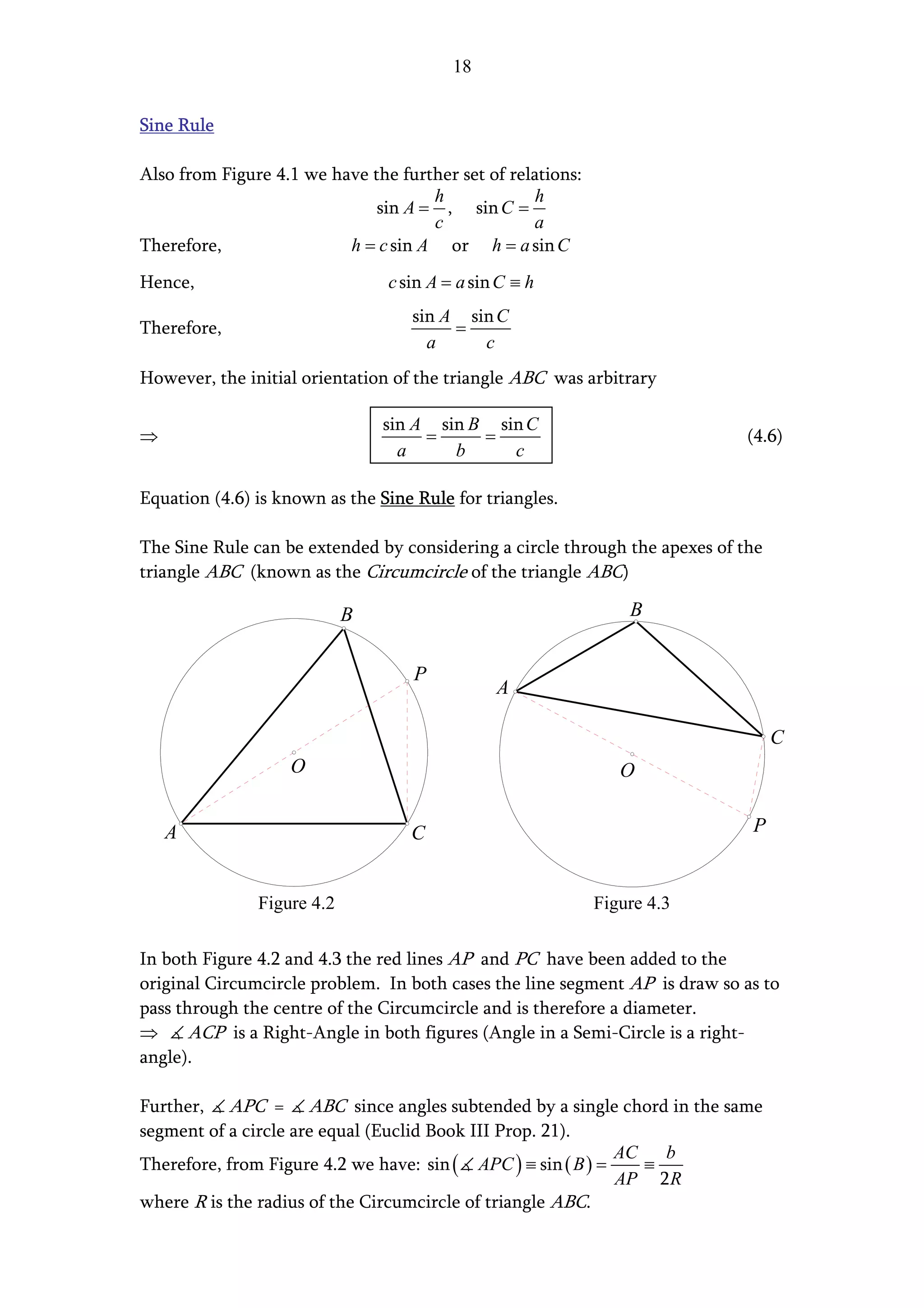

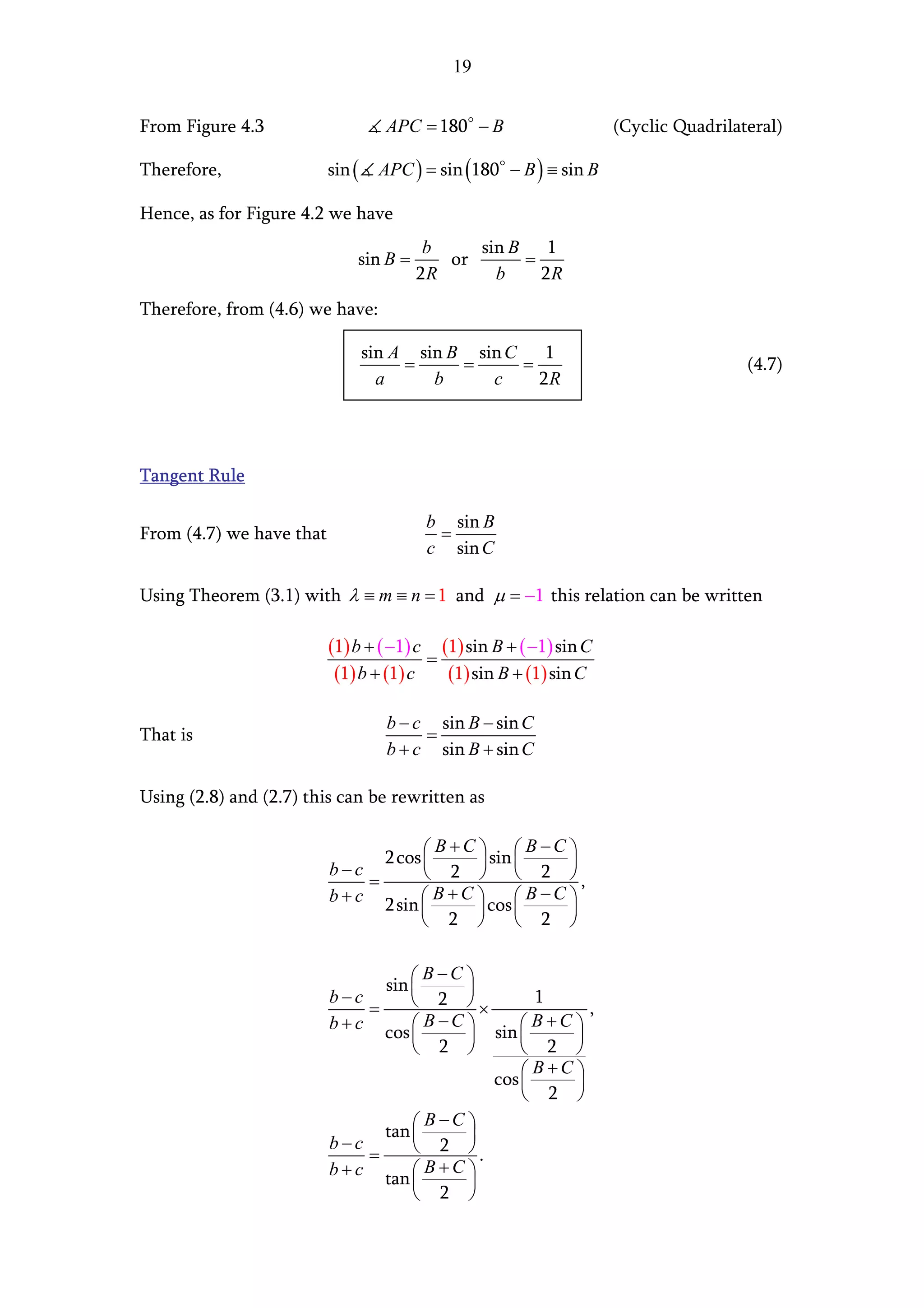

2. Using Pythagorean theorem applied to two triangles, it eliminates the height and derives an expression for the height solely in terms of the triangle's three sides, resulting in Heron's formula for the area.

![75

In order of usage:

Sixth Form Trigonometry. W. A. C. Smith. James Nisbet & Co. Ltd. [1956].

Modern Geometry. C. V. Durell. Macmillan & Co. Ltd. [1957].

Plane Trigonometry (Part 1). S. L. Loney. Macmillan & Co. Ltd. [1967].

A School Geometry (Parts I – VI) . Hall & Stevens. Macmillan & Co. Ltd. [1944].

Advanced Euclidean Geometry: An Elementary Treatise on the Geometry of the

Triangle and the Circle. Roger A. Johnson. Dover Publications Inc. [1929].

College Geometry: An Introduction to the Modern Geometry of the Triangle and

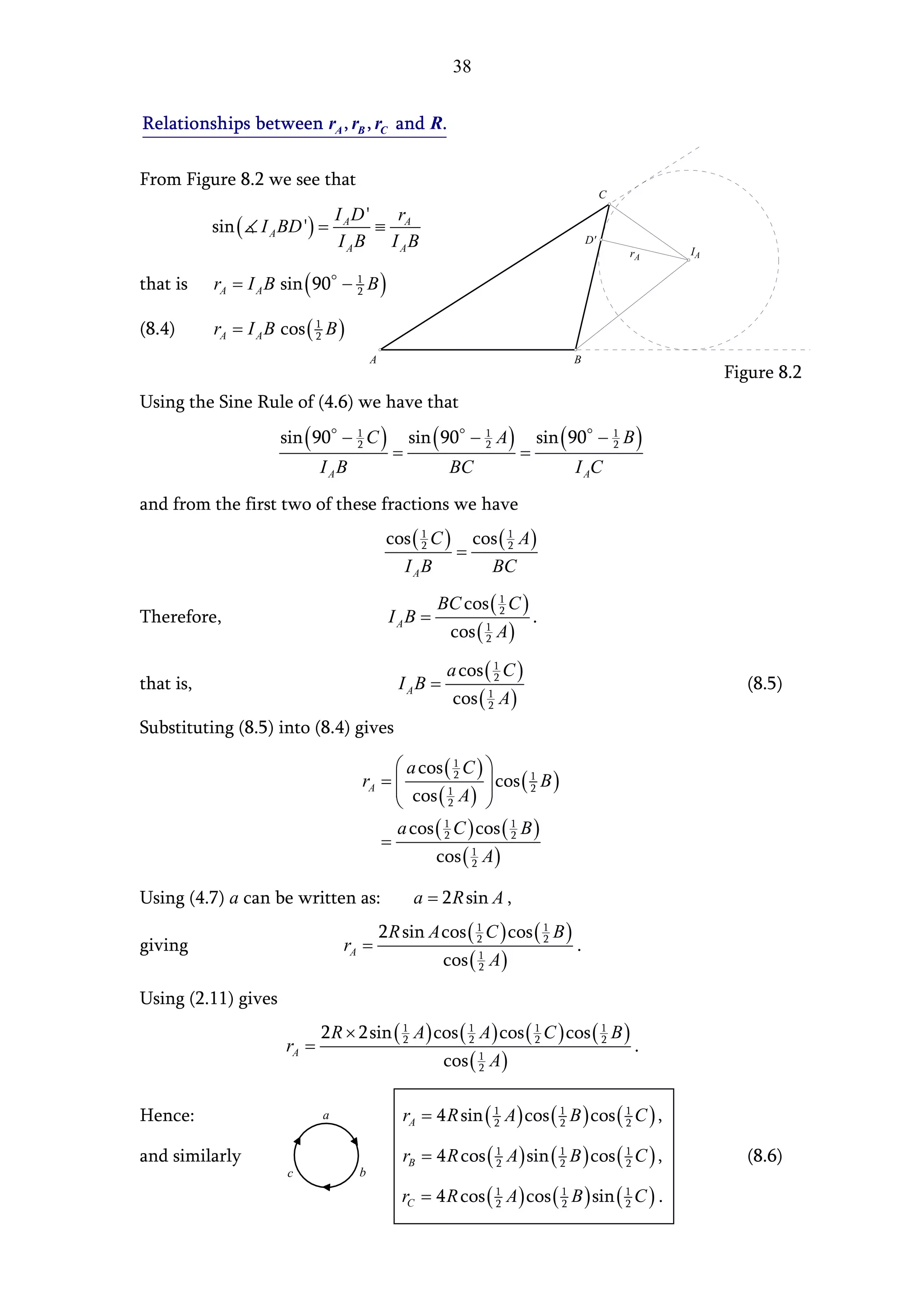

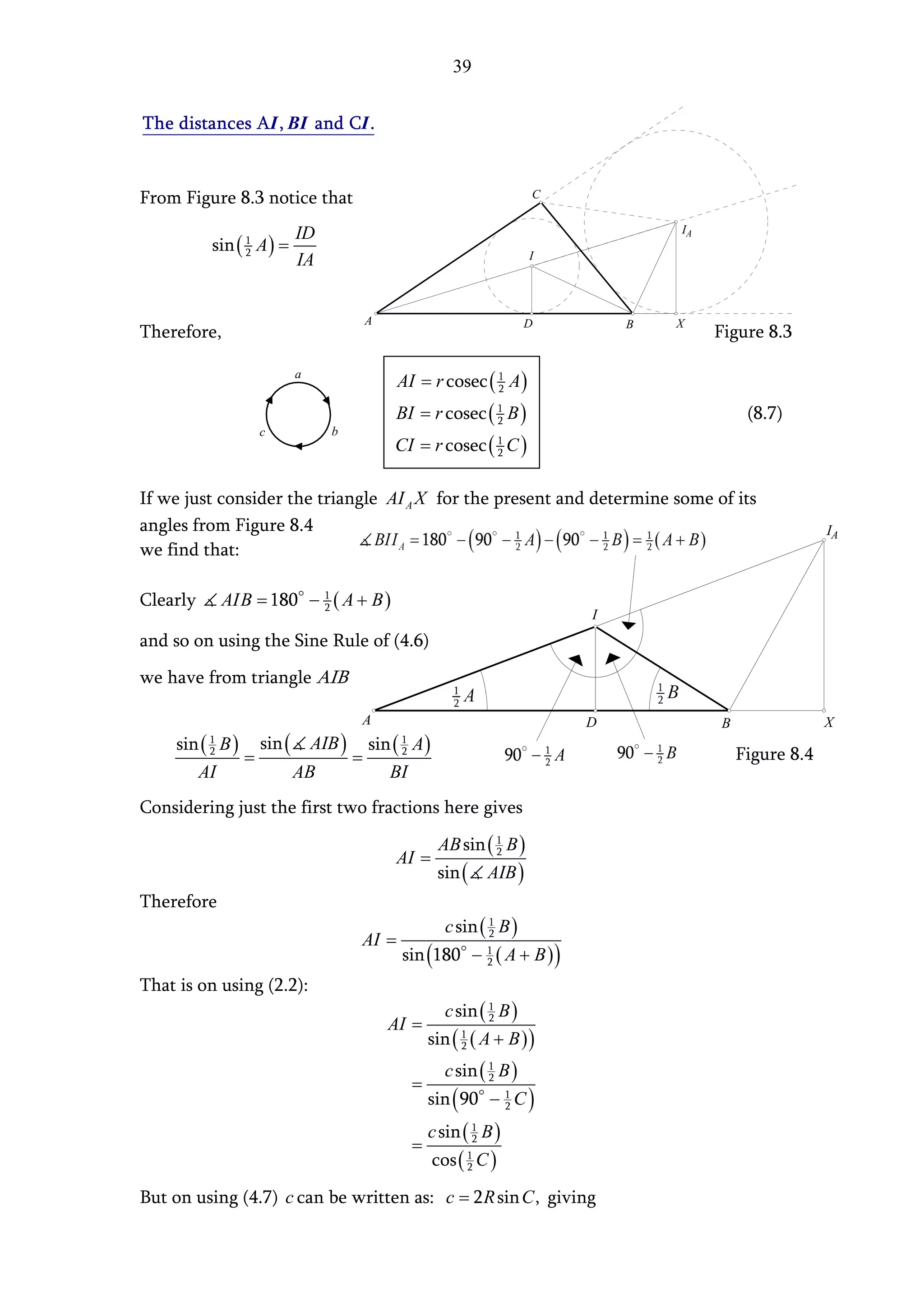

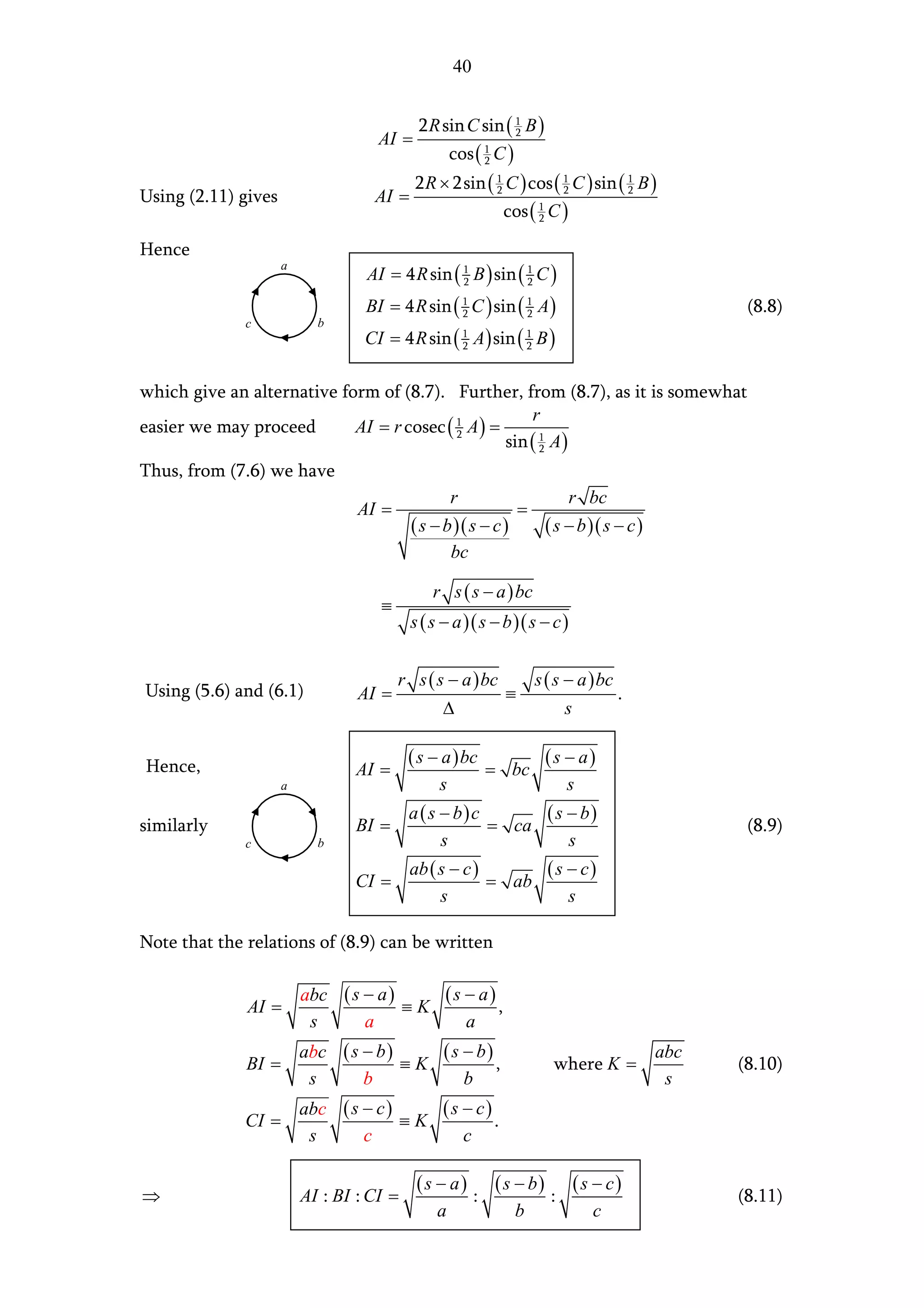

the Circle. N. Altshiller Court. Barnes & Noble Inc. [1952].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/elementary-triangle-goemetry-091014115846-phpapp02/75/Elementary-triangle-goemetry-75-2048.jpg)