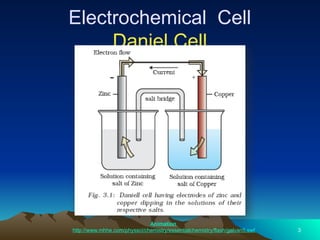

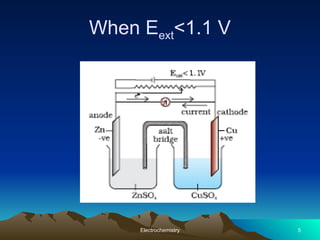

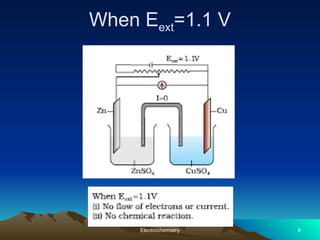

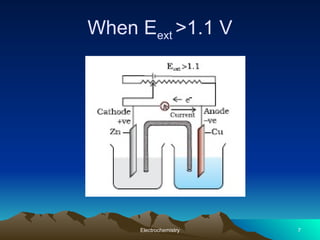

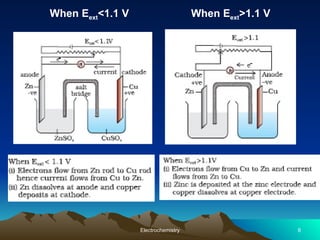

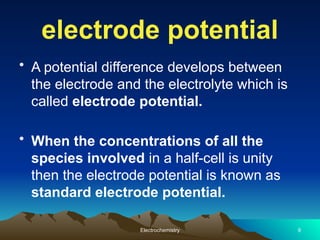

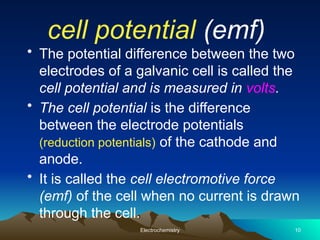

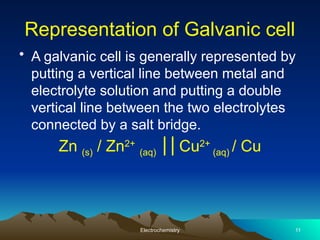

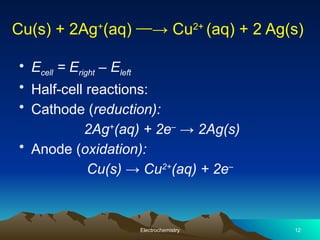

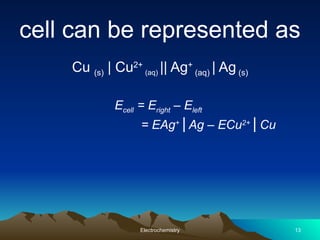

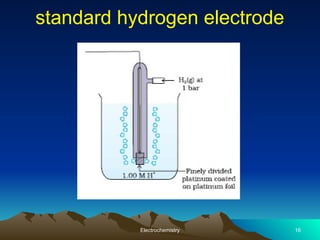

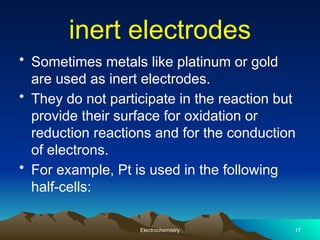

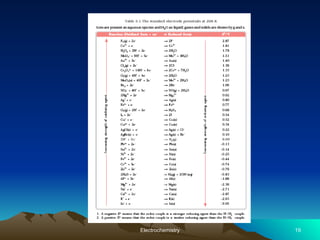

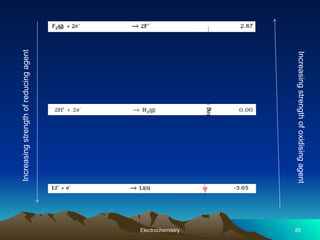

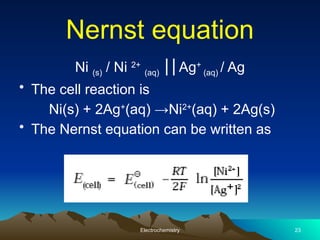

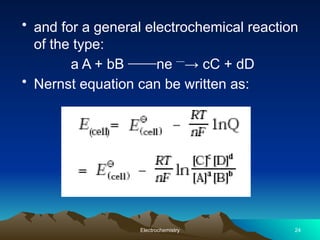

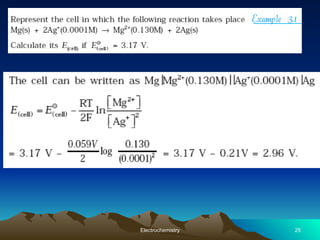

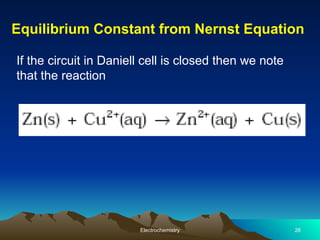

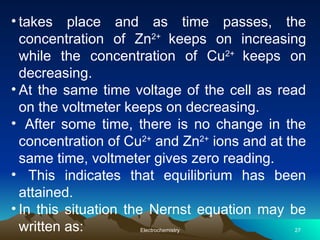

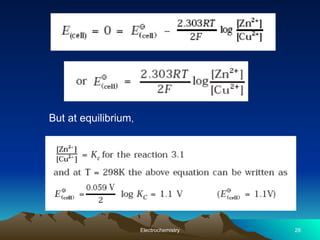

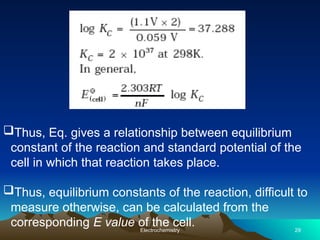

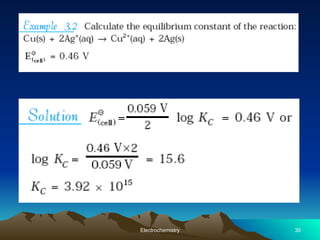

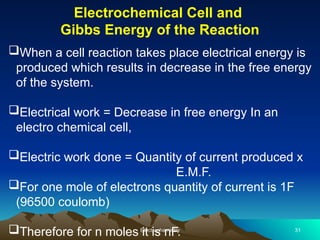

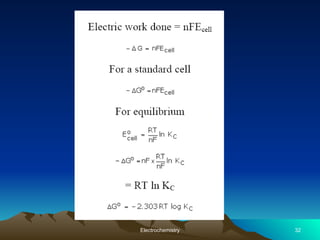

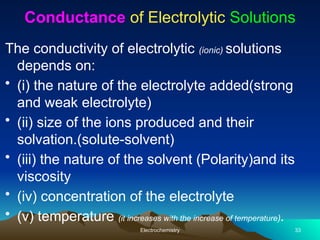

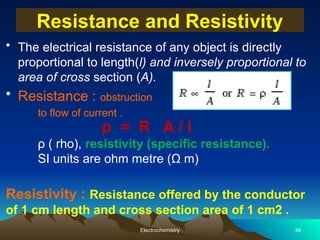

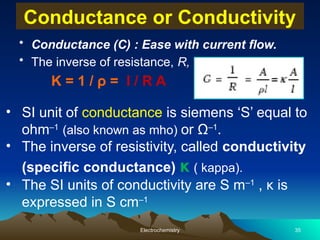

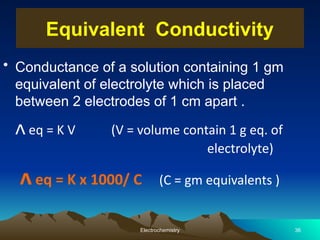

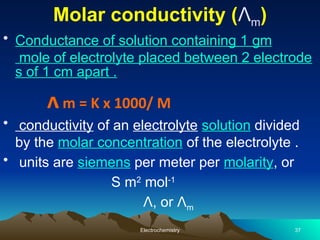

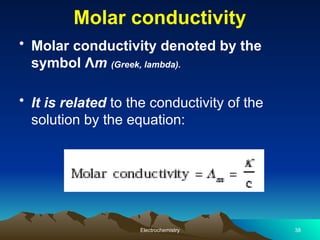

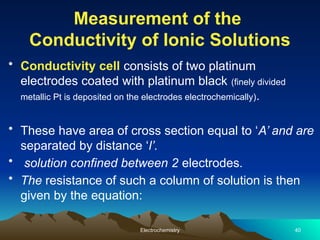

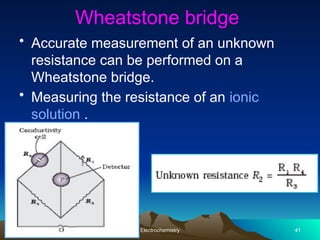

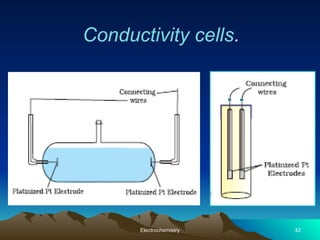

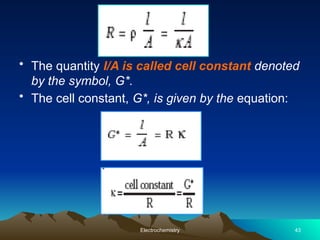

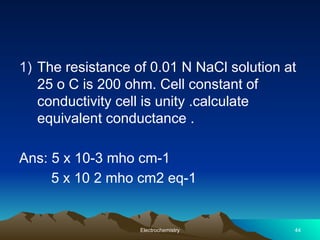

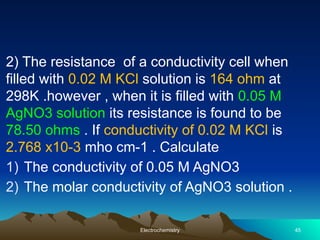

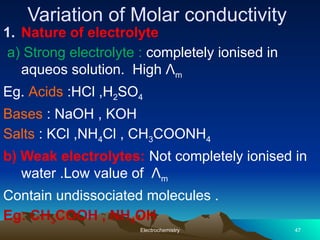

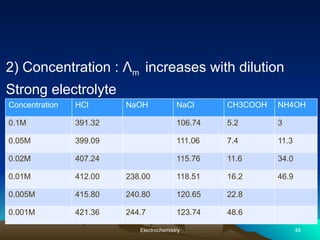

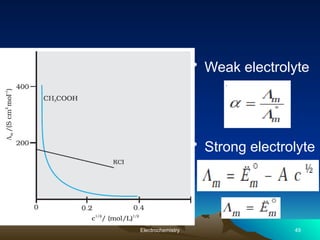

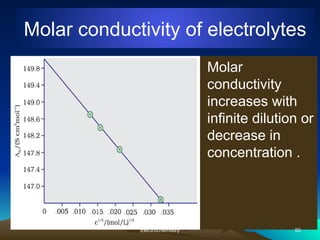

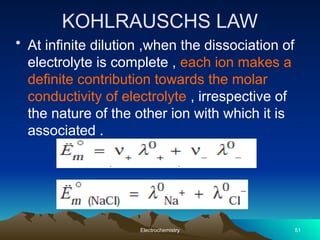

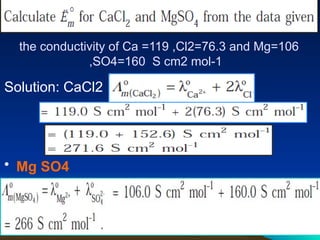

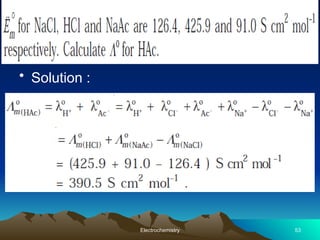

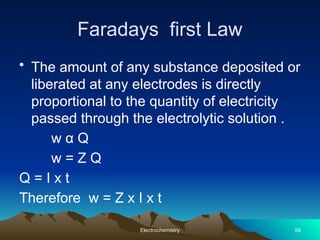

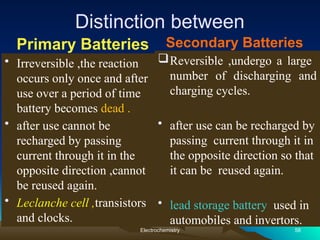

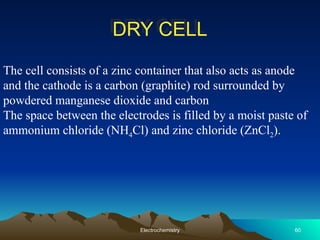

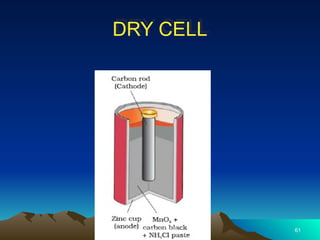

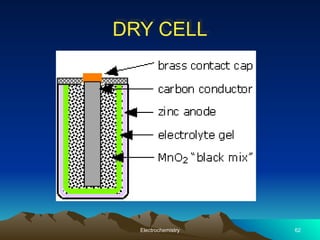

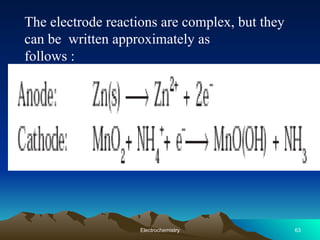

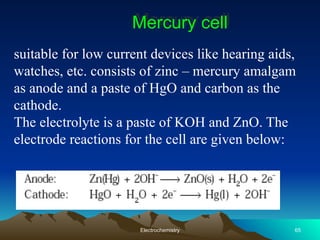

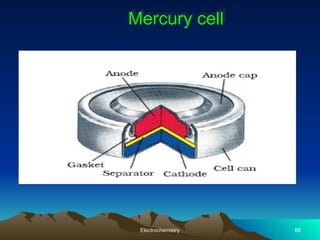

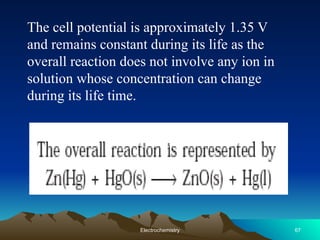

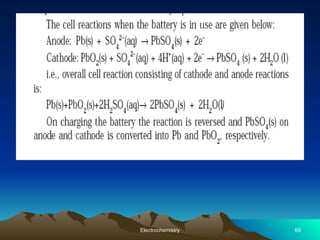

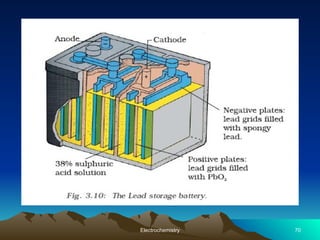

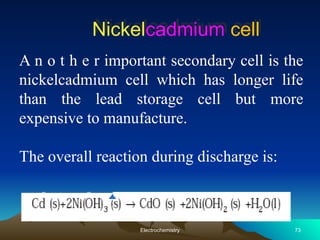

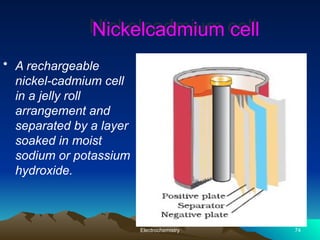

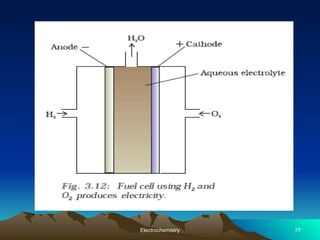

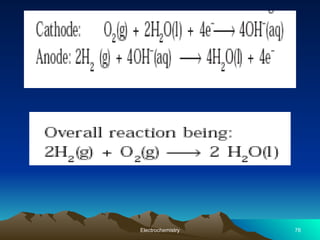

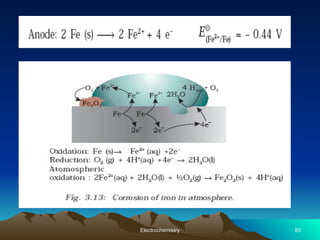

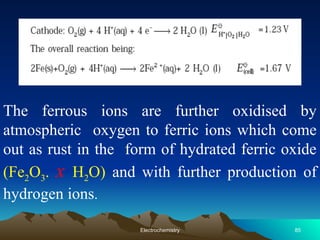

The document presents an in-depth overview of electrochemistry, covering topics such as redox reactions, electrochemical cells, conductivity measurements, and the principles governing batteries and fuel cells. It explains key concepts like standard electrode potential, Nernst equation, Faraday's laws, and variations in molar conductivity, alongside practical applications and examples. The document also addresses issues related to corrosion and the implications of electrochemical processes in various contexts.