Here's a summary of the eigenvalue problem for a general audience:

What is an eigenvalue problem?

An eigenvalue problem is a mathematical problem that involves finding a special value (called an eigenvalue) an

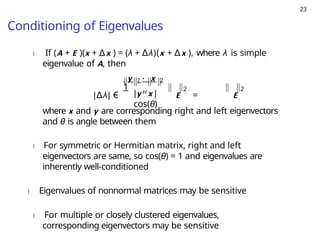

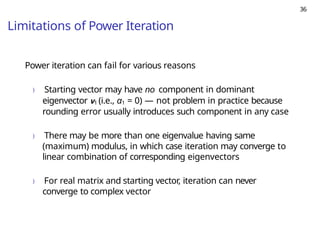

Eigenvalue problems can be challenging to solve, especially for large matrices. Some of the challenges include finding the eigenvalues and eigenvectors, dealing with non-unique solutions, and handling ill-conditioned matrices.

![14

Eigenspaces and Invariant Subspaces

) Eigenvectors can be scaled arbitrarily: if Ax = λx ,

then A(γx ) = λ(γx ) for any scalar γ, so γx is also

eigenvector corresponding to λ

) Eigenvectors are usually normalized by requiring some

norm of eigenvector to be 1

) Eigenspace = Sλ = {x : Ax = λx }

) Subspace S of Rn (or Cn ) is invariant if AS ⊆ S

) For eigenvectors x1 · · · xp , span([x1 · · · xp ]) is invariant

subspace](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eigenvaluepbm-numerical1-250413180702-1df32ec5/85/Eigenvalue-problems-numerical-methods-pptx-14-320.jpg)