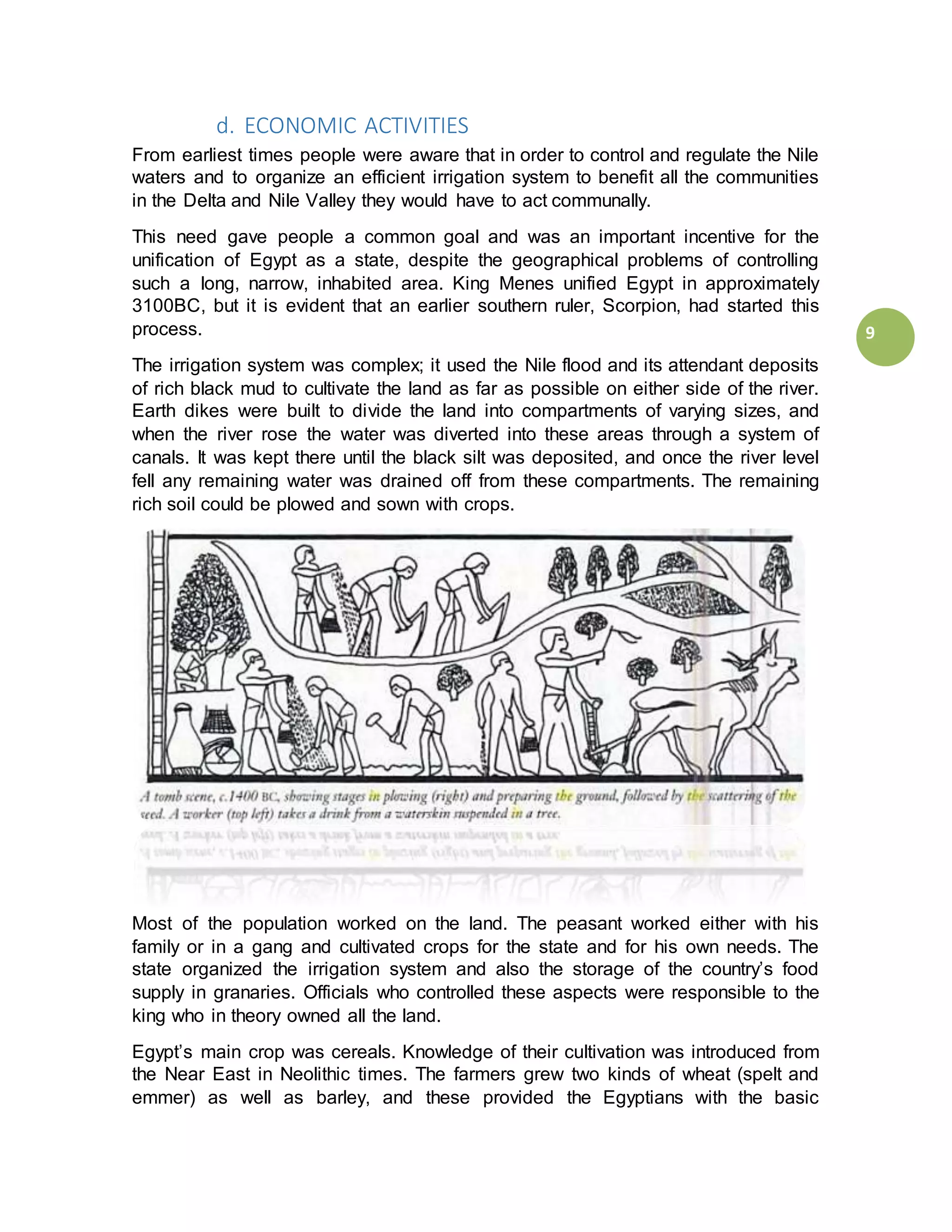

The document provides information on education and libraries in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. It discusses the time periods and locations of both civilizations, as well as their economic activities, natural resources, and approaches to education. Libraries were important in both societies for preserving knowledge and intellectual works.