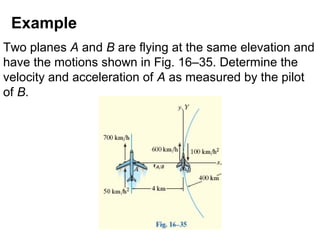

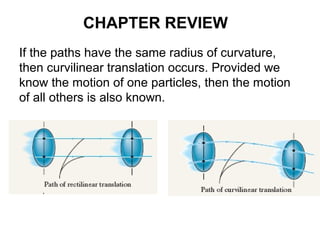

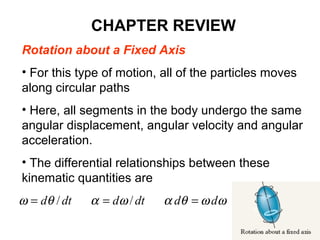

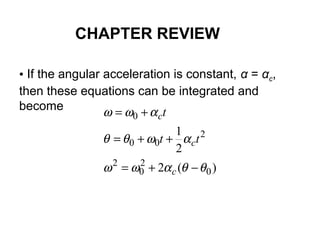

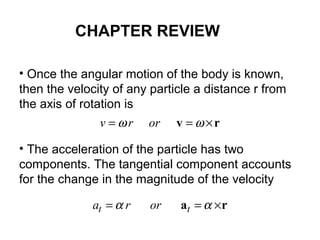

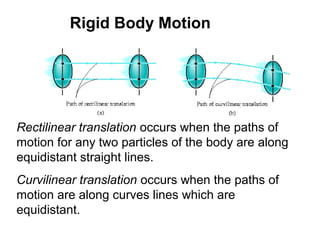

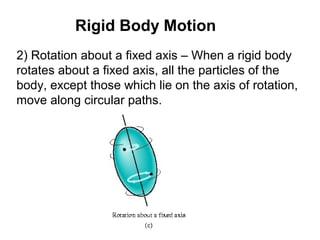

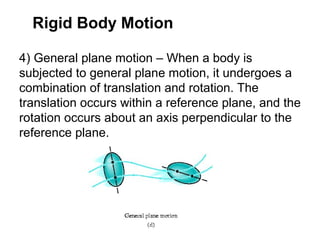

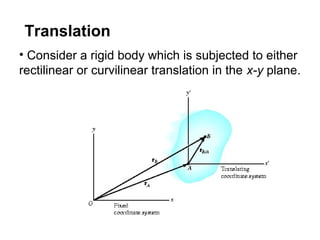

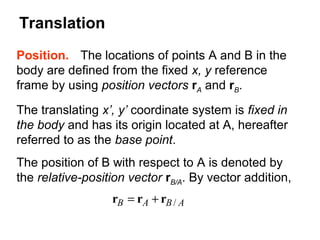

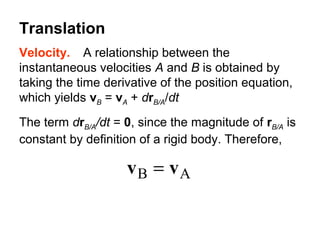

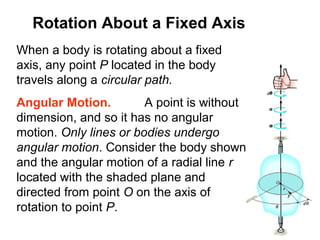

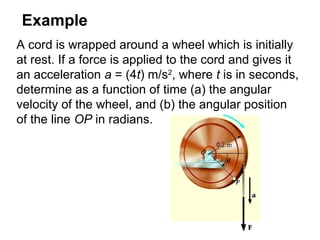

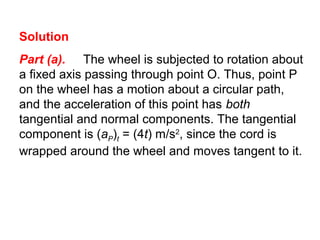

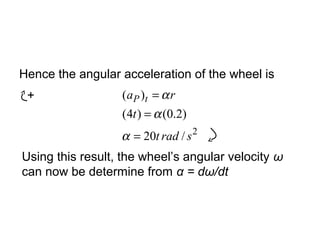

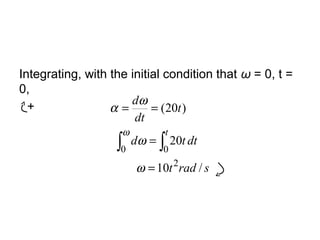

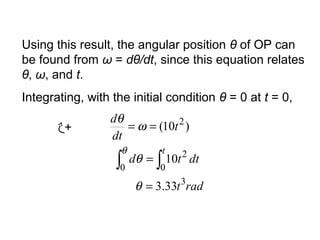

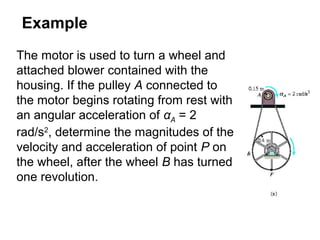

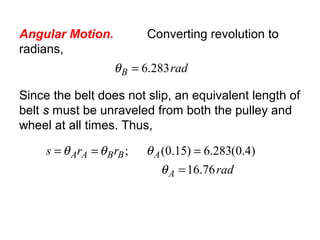

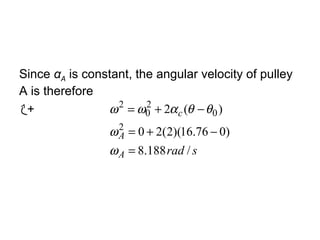

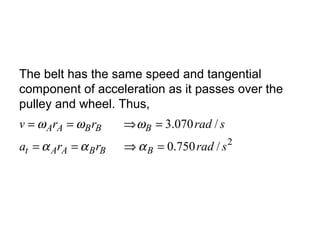

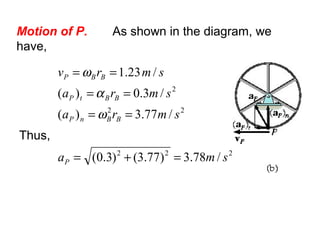

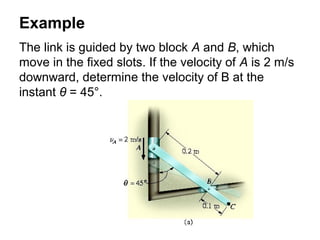

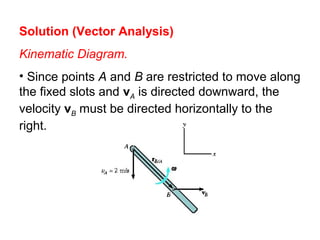

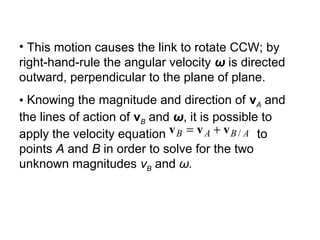

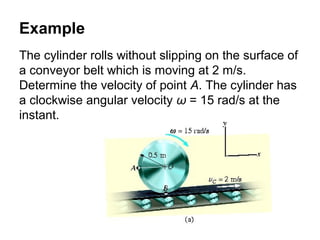

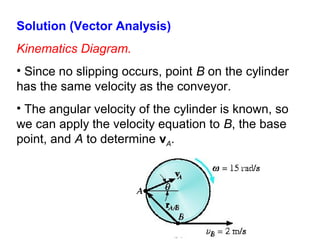

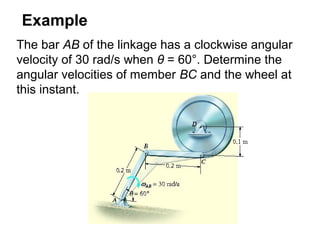

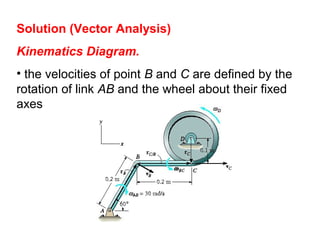

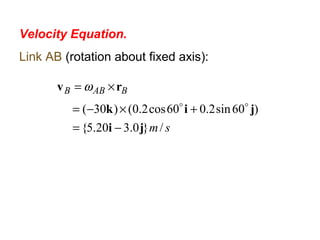

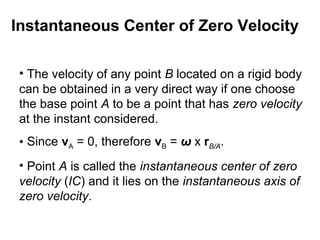

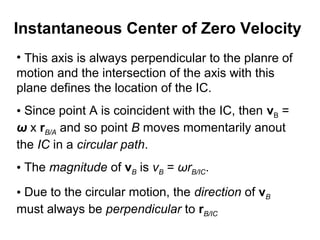

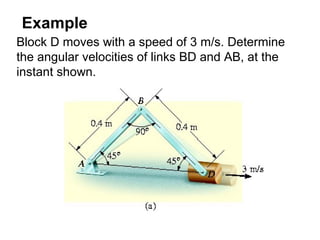

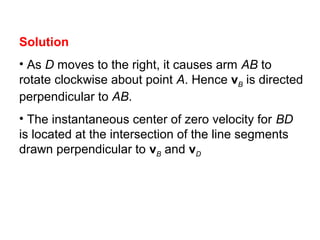

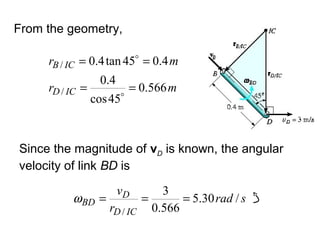

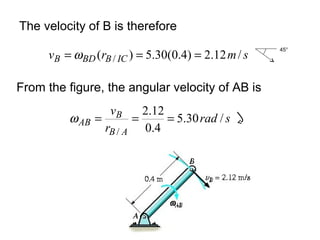

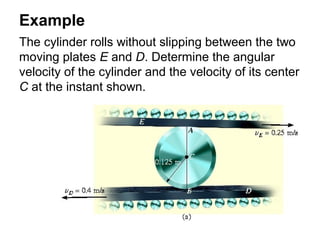

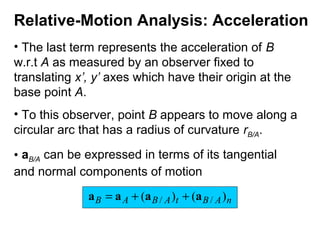

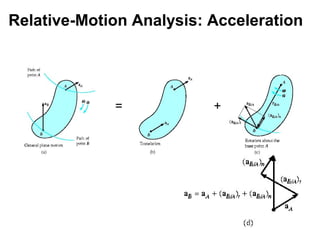

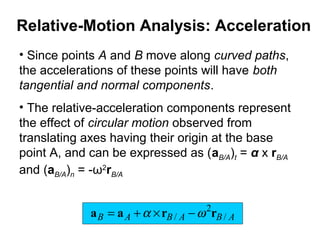

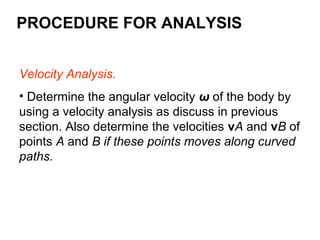

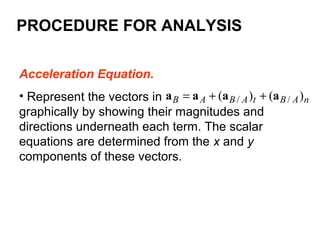

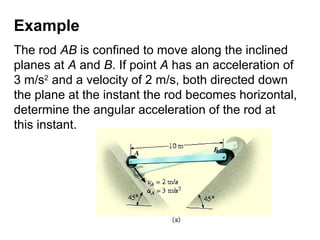

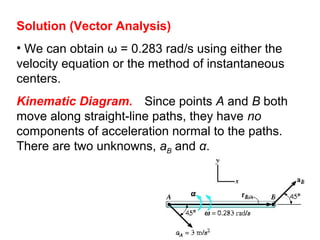

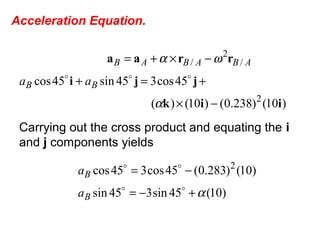

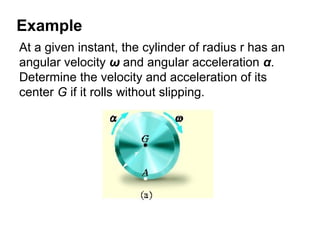

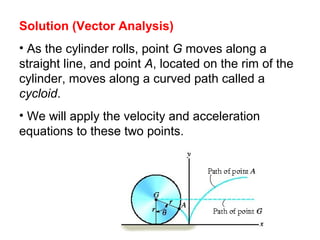

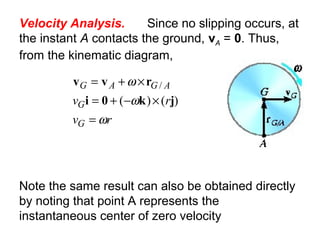

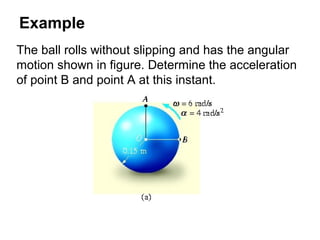

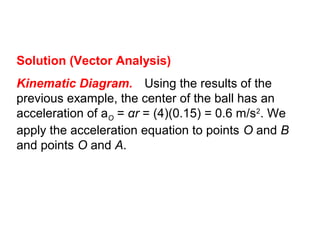

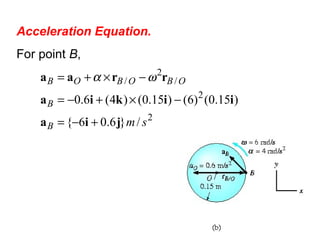

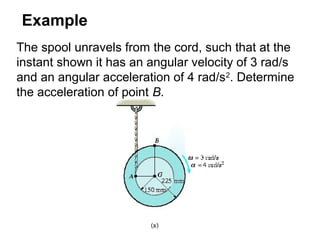

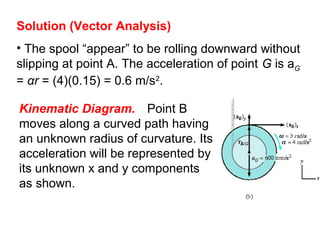

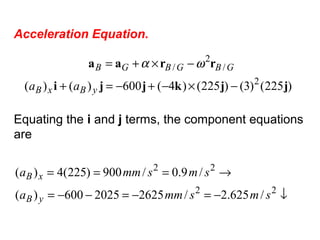

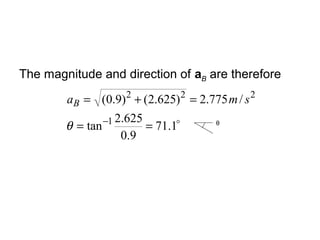

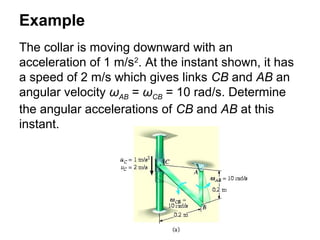

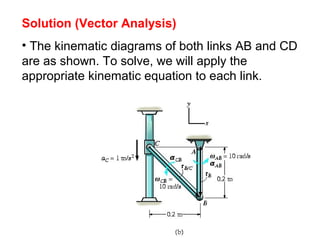

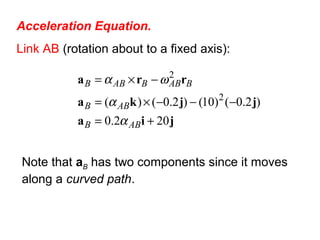

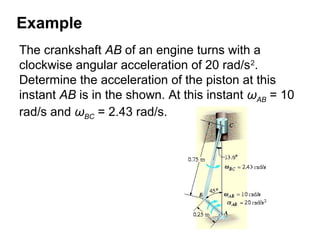

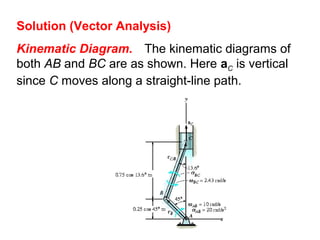

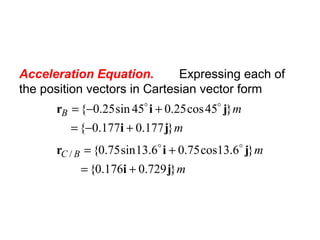

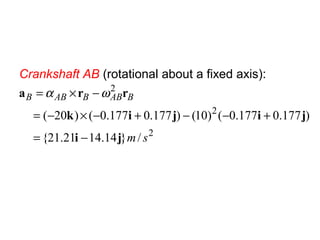

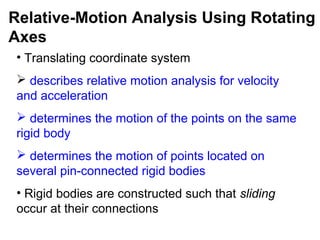

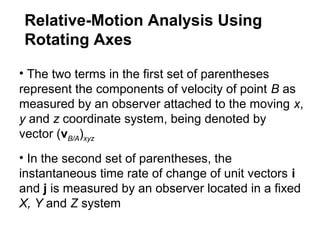

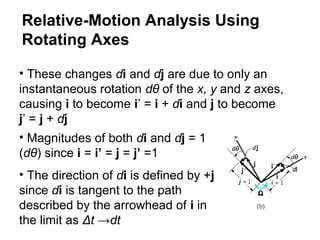

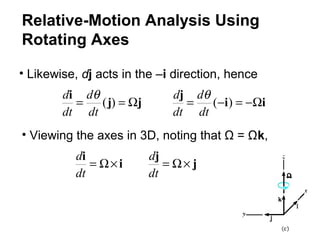

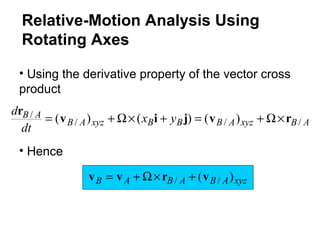

This document provides an overview of planar kinematics of rigid body motion. It describes three types of planar rigid body motion: translation, rotation about a fixed axis, and general plane motion. Translation can be rectilinear or curvilinear. Rotation about a fixed axis involves angular position, velocity, acceleration, and the motion of a point on the rotating body. General plane motion is a combination of translation and rotation. Formulas are provided for analyzing velocity and acceleration during these different types of motion. Examples are also given to demonstrate how to apply the kinematic equations.

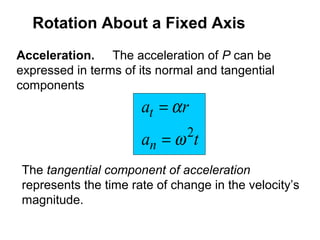

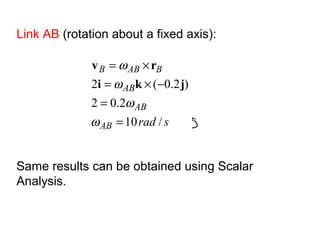

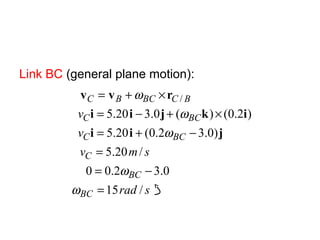

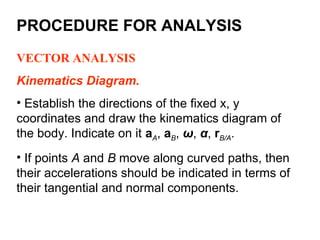

![Velocity Equation.

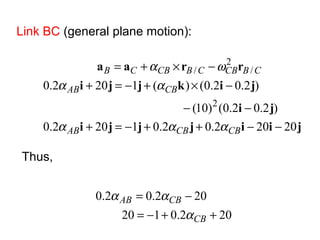

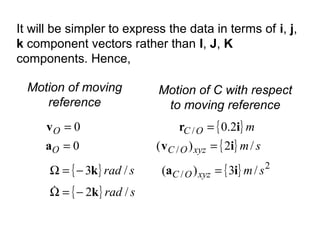

ijji

jikji

rvv

45cos2.045sin2.02

)]45cos2.045sin2.0([2

/

ωω

ω

ω

++−=

−×+−=

×+=

B

B

ABAB

v

v

Equating the i and j components gives

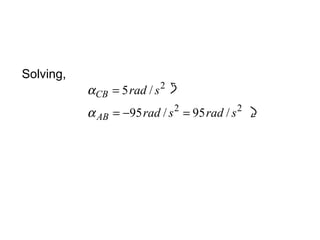

→=

=

+−==

smv

srad

v

B

B

/2

/1.14

45sin2.02045cos2.0

ω

ωω

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicslecture5-140613051813-phpapp01/85/Dynamics-lecture5-72-320.jpg)

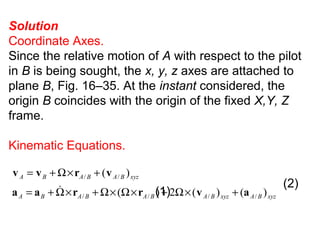

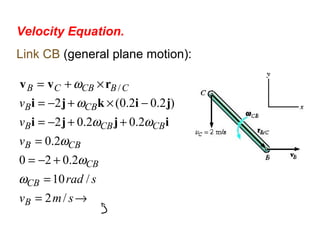

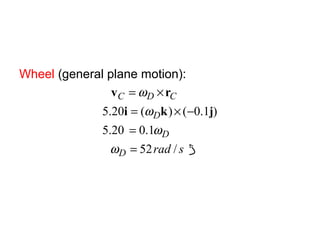

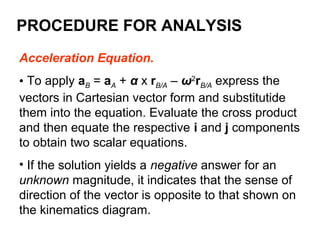

![Velocity Equation.

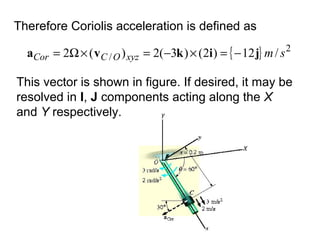

ijiji

jikiji

rvv

50.750.72)()(

)]5.05.0()15(2)()(

/

++=+

+−×−+=+

×+=

yAxA

yAxA

ABBA

vv

vv

ω

So that

smv

smv

yA

xA

/50.7)(

/50.950.72)(

=

=+=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicslecture5-140613051813-phpapp01/85/Dynamics-lecture5-75-320.jpg)

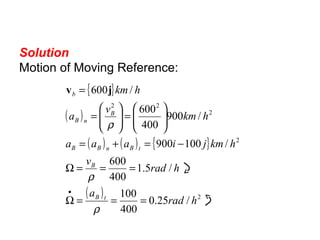

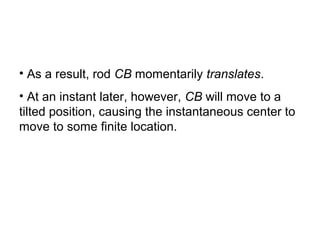

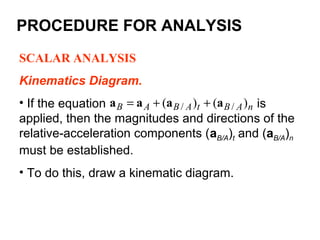

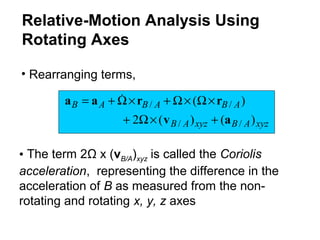

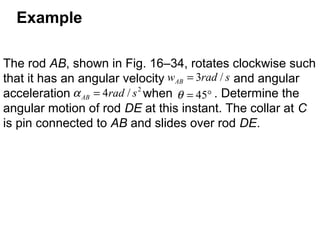

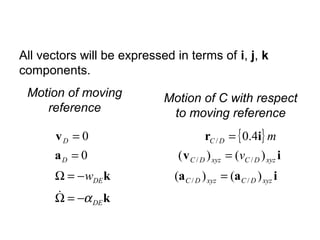

![The velocity and acceleration of the collar are

determined by substituting the data in the previous

2 equations and evaluating the cross products,

which yields,

{ }

[ ]

{ } 2

////

//

/4.1220.1

3)2()3(2)2.0()3()3()2.0()2(0

)()(2)(

/6.02

2)2.0()3(0

)(

sm

sm

xyzOCxyzOCOCOCOC

xyzOCOCOC

ji

iikikkik

avrraa

ji

iik

vrvv

−=

+×−+×−×−+×−+=

+×Ω+×Ω×Ω+×Ω+=

−=

+×−+=

+×Ω+=

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicslecture5-140613051813-phpapp01/85/Dynamics-lecture5-171-320.jpg)

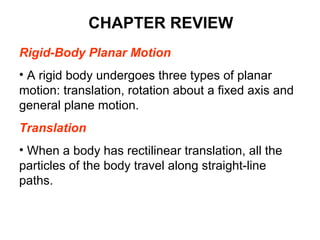

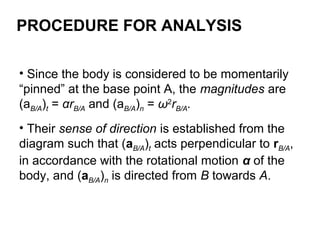

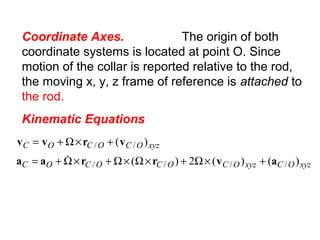

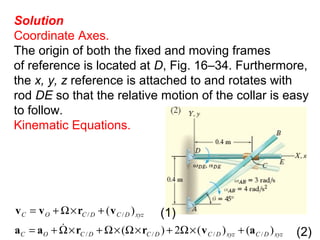

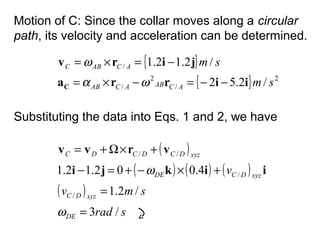

![( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]

( ) ( ) ( )

( )

22

2

/

/

////

/5/5

/6.1

2.132

4.0334.002.52

2

sradsrad

sma

DE

xyzDC

xyzDC

DE

xyzDCxyzDCDCDCDC

=−=

=

+×−+

×−×−+×−+=−−

+×Ω+×Ω×Ω+×Ω+=

•

α

α

iaik

ikkikji

avrraa](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dynamicslecture5-140613051813-phpapp01/85/Dynamics-lecture5-176-320.jpg)