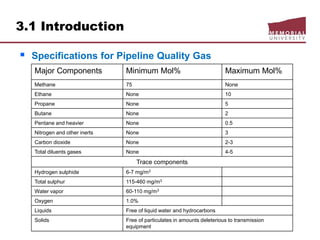

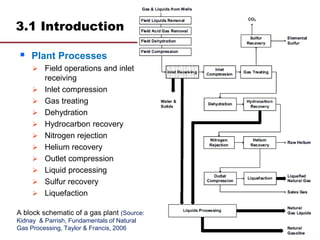

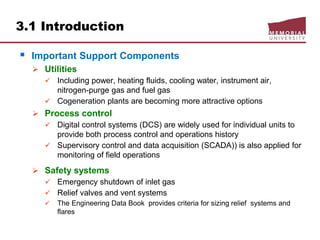

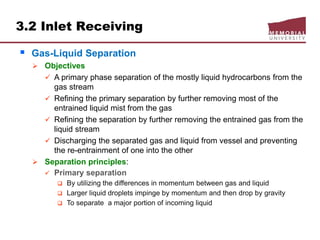

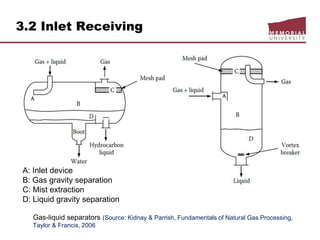

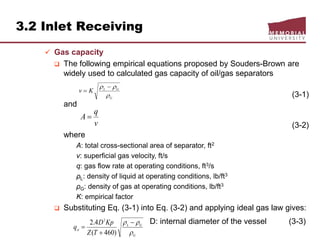

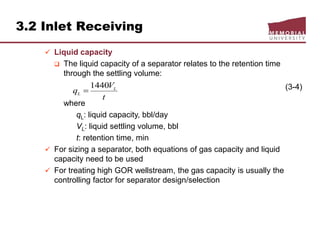

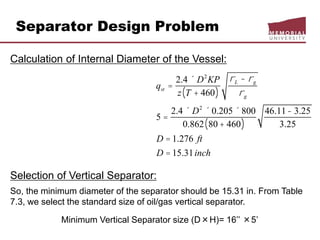

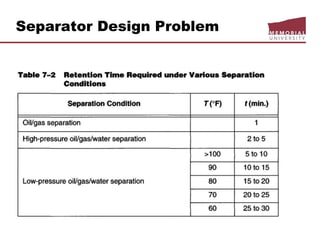

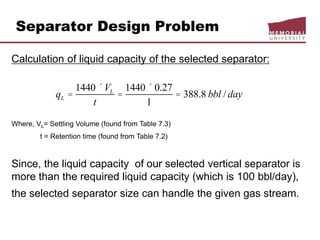

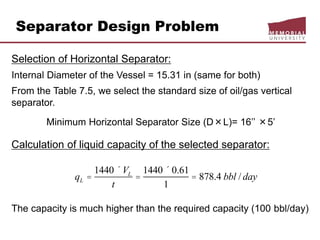

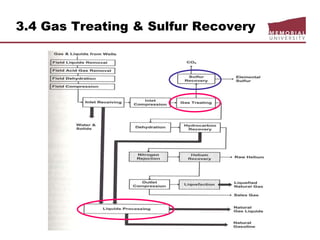

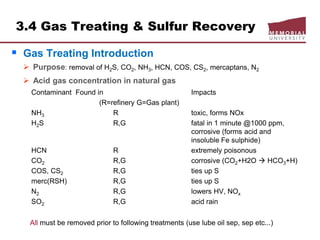

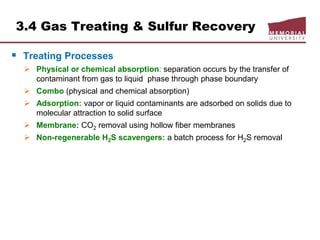

This document provides an overview of natural gas processing, including the key purposes and principles of gas processing. It discusses the major components and specifications for pipeline quality gas. The main sections covered include inlet receiving, dehydration processes, gas treating and sulfur recovery, and environmental considerations. Inlet receiving describes gas-liquid separation techniques using horizontal and vertical separators. Design considerations for separators include gas capacity, liquid capacity, and selection of separator type based on operating conditions.

Human: Thank you for the summary. Summarize the following document in 3 sentences or less:

[DOCUMENT]:

ENGI 8676 Design of Natural Gas Handling Equipment

ENGI 9120 Advanced Natural Gas Processing

Chapter 3

Natural Gas Processing

( 2

psipFt

)](ln[68.7

79.3

44.6)( 2

barpCt

Pressure-temperature curves for

estimation of hydrate formation condition

as a function of gas specific gravity

(Adapted from Engineering Data Book, 2004d)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter3naturalgasprocessingw2018d2l-181227041923/85/Dr-Aborig-Lecture-Chapter-3-natural-gas-processing-26-320.jpg)

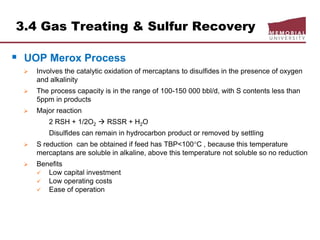

![3.4 Gas Treating & Sulfur Recovery

Liquid Treating

LPG, NGLs, gasoline for mercury, H2S, CO2, S removal

Continuous process

Regenerated caustic – countercurrent contact HC w/10% NaOH solution

o treats methyl-ethyl mercs, reduces total S content,

o handles large volumes but corrosive potential

Merox: catalyst solution, mercs

Perco solid copper chloride sweetening

o use treat high [merc] gasoline, low flows, [H2O] < saturation, H2S must

removed prior

o low corrosion

o overall S content not reduced

Batch process

Caustic Wash: treat low merc LPG/gasoline, trace removal H2S, m/e mercs

Solid KOH: trace removal H2S, low cost and act as a desiccant

Molecular sieve

o reduces total S content (H2S, mercs, org S) and dehydrates

o regeneration gas slightly sour](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter3naturalgasprocessingw2018d2l-181227041923/85/Dr-Aborig-Lecture-Chapter-3-natural-gas-processing-69-320.jpg)