1) The document is a dissertation submitted to ETH Zurich that studies invariant manifolds, passage through resonance, stability, and applies these concepts to a synchronous motor model.

2) It first develops theory for a general Hamiltonian system coupled to a linear system by weak periodic perturbations, showing the persistence of invariant manifolds. It then uses averaging techniques to analyze global dynamics, assuming a finite number of resonances.

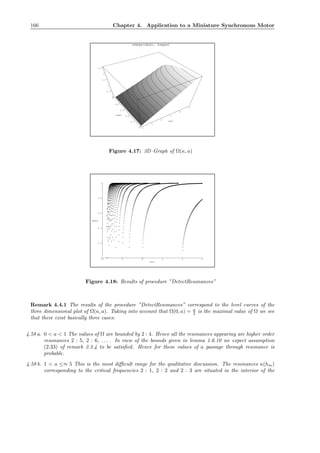

3) It represents the reduced system in a way suitable for stability analysis, covering both non-degenerate and degenerate cases.

4) The second part applies these methods to explicitly model a miniature synchronous motor, analytically deriving approximations and numerically simulating and confirming the dynamics, showing approach

![Introduction

The aim of this work is to study a particular type of miniature synchronous motor. Conventional syn-

chronous motors are characterized by the property that under working conditions the rotor exhibits a

stable rotation, the frequency being that of the power supply (hence the term ”synchronous”). In or-

der to enter the working conditions after switching on the motor, different techniques are suggested in

electrical engineering. Some of these techniques (such as pony motors, induction cages or electronic con-

trols) are rather complicated. Hence in many papers the transient behaviour upon start and the state

of synchronous rotation are treated separately. By contrast, the type of motor considered here features

a simple mechanism which permits a satisfactory physical modelling covering the entire process. This

model has been used by the manufacturer [12] for numerical studies and was presented in a colloquium

talk in the nineteen 80’s. It is represented by the following non–linear time–periodic system of ordinary

differential equations

d2

dτ2

ϑ = −

λ

J

i2

1 + i2

2 sin(ϕ) − ˜̺

d

dτ

ϑ − ˜m

U0 sin(ωτ) = R i1 + L

d

dτ

i1 + λ

d

dτ

sin(ϑ)

U0 sin(ωτ) = R i2 + L

d

dτ

i2 + λ

d

dτ

cos(ϑ) + u

d

dτ

u = i2/C.

(1)

The quantity ϑ is the angle of the rotor with respect to a fixed axis, i1 i2 correspond to the currents in

two parallel circuits and u describes the voltage of a condenser attached to the second power circuit.

Our approach for a mathematical treatise is based on perturbation theory. After some preliminary

transformations and assumptions on the parameters, the system turns out to be a special case of the

following problem

( ˙q, ˙p) = J∇H(q, p) + F(q, p, η, t, ε)

˙η = A η + G(q, p, t, ε).

(1.1)

This generalized problem consists of a one–degree of freedom Hamiltonian system (corresponding to the

mathematical pendulum in the above set of equations) and a linear system, the two being coupled by

small periodic perturbations. As this system is of interest by itself, we introduce a general framework

which might be of use elsewhere, too. The hypotheses we make reflect some of the features of the original

physical problem, however. As to the Hamiltonian system these assumptions include the existence of an

elliptic fixed point at the origin satisfying a non–resonance condition, as well as the existence of domains

foliated by periodic solutions (such as the oscillatory and rotatory solutions of the pendulum equation).

The matrix A is assumed to be exponentially asymptotically stable and the Fourier series with respect

to time t of the 2 π–periodic perturbations F and G are assumed to be finite.

v](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-9-320.jpg)

![vi Introduction

The original physical problem suggests two main questions. The discussion of the state of synchronous

rotation which is related to the existence and stability of a periodic solution near (q, p, η) = 0 and hence

is local in nature. On the other hand, solutions describing the transition from start to stationary rotation

are of upmost interest. They require a more global treatment. In a first part of this work a number of

key results for systems of type (1.1) are derived which prove to be a tool kit for concrete applications. In

a second part these results are applied to the miniature synchronous motor.

The first part is split into three self–contained chapters. In chapter 1 it is shown that the fixed point

(q, p, η) = 0 of the unperturbed system generates a unique 2 π–periodic solution. A discussion of its

stability is postponed until chapter 3. A time–dependant shift of the coordinates first yields a problem

which is again of type (1.1), i.e.

( ˙ˇQ, ˙ˇP) = J∇H( ˇQ, ˇP) + ˇF( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε)

˙H = A H + ˇG( ˇQ, ˇP, t, ε),

(1.16)

but satisfies ˇF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) = 0 and ˇG(0, 0, t, ε) = 0. For ε = 0, the ( ˇQ, ˇP)–plane H = 0 corresponds to

the center manifold of the origin, whereas the H–axis ( ˇQ, ˇP) = (0, 0) represents the stable manifold. For

ε = 0 sufficiently small we establish the existence of an integral manifold ( ˇQ, ˇP) = V(t, H, ε), the so–called

strongly stable manifold. This is achieved by adapting a result of Kelley [8] to our situation. Applying

the transformation ( ˇQ, ˇP) = (Q, P) + V(t, H, ε) then yields a system of the form

( ˙Q, ˙P) = J∇H(Q, P) + ˆF(Q, P, H, t, ε)

˙H = A H + ˆG(Q, P, H, t, ε),

(1.87)

where in particular ˆF vanishes on the new H–axis, i.e.

ˆF(0, 0, H, t, ε) = 0 ˆG(0, 0, 0, t, ε) = 0. (1.88)

In a next step we replace (Q, P) by action–angle coordinates (ϕ, h) ∈ R2

. The transformed system is

equivalent to (1.87) if we restrict (Q, P) to regions of periodic solutions of ( ˙Q, ˙P) = J∇H(Q, P). In view

of (1.88) such a region may be a neighbourhood of the fixed point (Q, P, H) = (0, 0, 0) as well. In this

case, the set (h, H) = (0, 0) corresponds to (Q, P, H) = (0, 0, 0) and is invariant. The stability discussion

of (h, H) = (0, 0) therefore yields information on the stability of (Q, P, H) = (0, 0, 0) which eventually

corresponds to synchronous rotation in the case of our model of a synchronous motor. In action–angle

coordinates the system is of the form

˙ϕ = ω(h) + f(t, ϕ, h, H, ε)

˙h = g(t, ϕ, h, H, ε)

˙H = A H + h(t, ϕ, h, H, ε)

(1.110)

where A still denotes the matrix introduced in (1.1) and f, g, h vanish for ε = 0. The unperturbed

problem corresponding to (1.110) suggests the existence of an attractive invariant manifold near H = 0.

The majority of results on the existence of such manifolds (see e.g. Fenichel [4], Hirsch, Pugh, Shub

[6]) are based on a discussion of Lyapunov type numbers of solutions. For the purpose of this work

an approach based on more easily accessible quantities is more convenient, see Kirchgraber [9]. In this

work we apply an adaption by Nipp/Stoffer [13] where the assumptions are expressed in terms of the

vector field. It is here where the introduction of action–angle coordinates turns out to be advantageous.

The attractive invariant manifold we establish admits the representation H = S(t, ϕ, h, ε) with S = 0

for ε = 0. Since all solutions of (1.110) approach the invariant manifold, the discussion then reduces to

the reduced system, i.e. the restriction of eq. (1.110) to the attractive invariant manifold. This reduced

system is two–dimensional but non-autonomous. It is represented in two different forms, either of which

will be used in chapter 2 and chapter 3, respectively.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-10-320.jpg)

![Introduction vii

The first representation of the reduced system given in chapter 1 is used for the global discussion. Taking

into account some additional properties of the original physical problem, chapter 2 deals with a system

of the form

˙ϕ = ω(h) +

3

j=2

εj

k,n∈Z

fj

k,n(h) ei(kϕ+nt)

+ ε4

f4

(t, ϕ, h, ε)

˙h =

3

j=2

εj

k,n∈Z

gj

k,n(h) ei(kϕ+nt)

+ ε4

g4

(t, ϕ, h, ε)

(2.1)

defined for ϕ, h ∈ R. Given km, nm ∈ Z and hm ∈ R such that gj

km,nm

= 0 (j ∈ {2, 3}) and km ω(hm) +

nm = 0 the value hm is called a resonance. We assume that the set of resonances hm is finite. Moreover,

for every resonance hm we require that d

dh ω(hm) = 0 holds. In order to obtain information on the

qualitative behaviour of (2.1) averaging techniques are applied. More precisely we apply time–dependant

near–identity transformations of the form ¯h = h + O(ε2

). This change of coordinates is defined in a

standard way, see Kirchgraber [11] or Sanders/Verhulst [17]. We use it in a somewhat different way,

however. As the transformation is singular in every resonance, it is applied outside a neighbourhood of

the resonances. In order to keep the higher order terms small, the size of the neighbourhood of each

resonance must be chosen appropriately. We show that the neighbourhoods omitted may be chosen to be

O(ε)–small. More precisely, for fixed δ > 0 and choosing |ε| < εO

(δ) the transformation may be applied

outside |ε|

δ –neighbourhoods of the resonances. In this outer region the transformed system then takes the

form

˙ϕ = ω(¯h) + O(ε)

˙¯h = ε2

g2

0,0(¯h) + ε2

δ2

¯g2

(t, ϕ, ¯h, ε, δ) + O(ε3

).

(2.23)

where ¯g2

is still bounded. If on a subset of the outer region the map g2

0,0 is bounded from below, the

parameters δ and |ε| < εO

(δ) may be chosen such that ˙¯h > 0 and thus all solutions leave this subset.

Away from zeroes of g2

0,0 the qualitative behaviour is therefore determined simply by the sign of g2

0,0.

In the inner region, i.e. if h satisfies |h − hm| < 4 |ε|

δ , a different near–identity change of coordinates is

defined. The resulting system then reads as follows

˙ϕ = ω(¯h) + O(ε2

)

˙¯h = ε2

g2

0,0(¯h) + ε2

l∈N∗

g2

lkm,lnm

(¯h) eil(kmϕ+nmt)

+ O(ε3

). (2.25)

Introducing the inner variables

ε ˜h := const ¯h − hm ∀ ¯h − hm < 4

|ε|

δ

ψ := km ϕ + nm t,

(2.28)

and taking into account again some special features which arise in the application of the synchronous

motor, the system takes the form of a km 2 π–periodically perturbed pendulum with external torque,

i.e. it is given by

˙ψ = ε ˜h + ε2 ˜f2

(t, ψ, ˜h, ε)

˙˜h = ε (a0 + ac

1 cos(ψ) + as

1 sin(ψ)) + ε2

˜g2

(t, ψ, ˜h, ε).

(2.29)

The quantities a0, ac

1 and as

1 are determined by the Fourier coefficients g2

0,0 and g2

km,nm

evaluated at

h = hm.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-11-320.jpg)

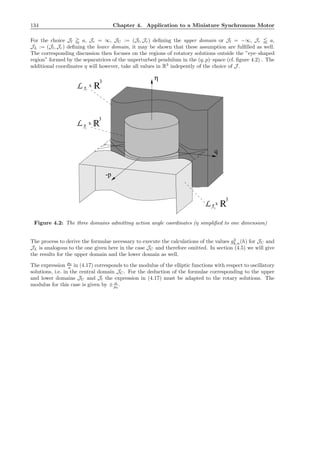

![Introduction ix

In the second part, chapter 4, we present the application of part one to the model of a miniature

synchronous motor mentioned before. After some preliminary preparations eq. (1) is transformed into

˙q = p

˙p = −

a

2

2

sin(q) + ε (η1 cos(q + t) − η2 sin(q + t)) − ε2

̺ p − ε2

(m + ̺)

˙η1 = −η1 + ε sin(q + t)

˙η2 = −η2 − 2 η3 + ε cos(q + t)

˙η3 = η2 − ε cos(q + t).

(4.14)

The quantity a is rougly equal to λ

R . For fixed a the perturbation parameter ε is given by a λ

U0

.

Here we assume that the voltage U0 of the power supply and the moment of inertia J of the motor are

proportional. Thus, ε tends to 0 provided U0 (and thus J) increases, while the magnetic dipol λ, and the

resistance R are kept fixed. By consequence, the effect of induction generated by the rotating permanent

magnet and exerted on the coils decreases as ε → 0.

In order to obtain preliminary insight into the features of (4.14) we present the results of various nu-

merical simulations carried out with the help of the package dstool [3]. The results found confirm the

analytical discussion given later in this chapter. In addition, they demonstrate that the behaviour in a

neighbourhood of the separatrix of the unperturbed problem of (4.14) is of no particular interest if a is

large. (Since the techniques introduced in part one rely on regions of periodic solutions of the Hamiltonian

system, the neighbourhood of a separatrix is not covered by our analytical approach.)

The main task in chapter 4 is to apply the tools of part one to system (4.14) and to compute the key

quantities g2

0,0(h), g2

km,nm

(h) and g,1

0,0(ε). Among other things this amounts to explicitely construct

suitable approximations of the invariant manifolds introduced in chapter 1. The introduction of action–

angle coordinates associated with the pendulum equation, is based on Fourier series of Jacobian elliptic

functions. Eventually g2

0,0(h) and g2

km,nm

(h) are represented with the help of convolutions of Fourier

series. The complexity of this procedure requires the use of a software package for symbolic and numerical

computations. The author has chosen the Maple [15] software package. Its synthax is simple and legible

for readers with basic knowledge in programming. Hence the source code listed is comprehensible to a

growing community. For various choices of the parameters the dynamics of the model is discussed in terms

of the physical behaviour of the motor. The influence of a mechanical friction (given by the parameter

˜̺) and an external torque ( ˜m) is considered as well. Both situations considered in chapter 2, i.e. the

case of passage of all solutions up to an O(ε)–set as well as the passage of strictly all solutions through

resonances are established. The periodic solution near the origin, corresponding to the synchronous

rotation of the shaft, is shown to be stable for all choices of the parameters. Moreover additional results

are established: the possibility of asynchronous rotations, the modulation of the synchronous rotation

state by a second harmonic as well as a synchronous rotation with large variation of the angular speed

(caused by a capture into resonance). The overall conclusion is that for sufficiently large a the motor

behaves favouritely, i.e. enters the state of stable synchronous rotation when switched on.

Chapter 4 closes with a result on the separatrix region for sufficiently small values of the parameter

a. In this situation, the existence of a global attractive invariant manifold of (4.14) is established. The

corresponding reduced system then is of periodically perturbed pendulum type. Although an approximate

representation of the reduced system is not available, the construction of an approximate Melnikov

function is feasible. The numerical evaluation of the corresponding formula then confirms the results

found by numerical simulation. More precisely, it is established that solutions starting with a frequency

larger than the frequency of the power supply may either enter the state of synchronous rotation or the

frequency may eventually tend to zero.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-13-320.jpg)

![1.2. The Periodic Solution 7

1.2.2 The Transformation into the Periodic Solution

The purpose of this section is to transform the coordinates of system (1.1) in a way, such that the origin

becomes a fixed point. This may be done by performing a (time–dependent) translation into the periodic

solution (ˇq, ˇp, ˇη).

More precisely we will use the Taylor / Fourier expansions (1.3), (1.4) assumed in GA 1.3 to explicitely

calculate a similar representation of the corresponding vector field in the new coordinates. This will be

prepared in the following lemma:

Lemma 1.2.3 Consider a linear inhomogenous differential equation on R2+d

of the following type

˙x = B x +

|n|≤N

bneint

, (1.13)

where bn ∈ C2+d

for every |n| ≤ N, bn = b−n and σ (B)∩i Z = ∅. Then there exists a unique 2π–periodic

solution given by

x(t) =

|n|≤N

[i n IC 2+d − B]−1

bn eint

. (1.14)

PROOF: Note first that since σ (B) ∩i Z = ∅, the inverse of the matrix i n IC 2+d − B exists. It is evident

that the function x presented in (1.14) is 2π–periodic with respect to t. Moreover

˙x(t) − B x(t) =

|n|≤N

i n [i n IC 2+d − B]

−1

bn eint

− B

|n|≤N

[i n IC 2+d − B]

−1

bn eint

=

|n|≤N

[i n IC 2+d − B] [i n IC 2+d − B]

−1

bn eint

=

|n|≤N

bn eint

,

such that x is a solution of (1.13), indeed.

Consider any further 2π–periodic solution y of (1.13). Writing its Fourier expansion y =

n∈N

cn eint

and

calculating ˙y−B y one then compares the result with

|n|≤N

bn eint

which implies cn = [i n IC 2+d − B]

−1

bn

and thus x = y. Hence x is unique as claimed.

We now are in the position to prove the main result of this section.

Proposition 1.2.4 Let (ˇq, ˇp, ˇη) denote the 2π–periodic solution of system (1.1) for |ε| < ε1, asserted in

lemma 1.2.2 and perform the following change of coordinates in the (q, p, η, t, ε)–space:

(q, p, η, t, ε) = ((ˇq, ˇp, ˇη)(t, ε), 0, 0) + ( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε), (1.15)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-21-320.jpg)

![8 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

where2

( ˇQ, ˇP) ∈ R2

, H ∈ Rd

, t ∈ R and |ε| < ε1. Then (1.1) transforms into the system

( ˙ˇQ, ˙ˇP) = J∇H( ˇQ, ˇP) + ˇF( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε)

˙H = A H + ˇG( ˇQ, ˇP, t, ε),

(1.16)

where the following statements hold :

• The mappings ˇF and ˇG are of class Cω

, vanish at the origin ( ˇQ, ˇP, H) = 0 and admit the repre-

sentation3

ˇF( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε) =

3

j=1

εj ˇFj

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) + ε4 ˇF4

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε)

ˇG( ˇQ, ˇP, t, ε) =

3

j=1

εj ˇGj

( ˇQ, ˇP, t) + ε4 ˇG4

( ˇQ, ˇP, t, ε)

(1.17)

where ˇFj

and ˇGj

, (j = 1, . . . , 4) are 2π–periodic with respect to t.

• The map H → ˇF( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε) is affine.

• The mappings ˇF1

, ˇF2

, ˇG1

and ˇG2

may be expressed in terms of the original vector field of system

(1.1):

ˇF1

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) = F1

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) −

|n|≤N

∆(n, ˇQ, ˇP) F1

n(0, 0, 0) eint

ˇF2

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) = F2

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) −

|n|≤N

∆(n, ˇQ, ˇP) F2

n(0, 0, 0)eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

1

2 JD3

H( ˇQ, ˇP) α1,1

n,1, α1,1

¯n,1

+ ∂(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂(q,p)F1

n (0, 0, 0) α1,1

¯n,1

+ ∂ηF1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂ηF1

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

¯n,2 ei(n+˜n)t

ˇG1

( ˇQ, ˇP, t) = G1

( ˇQ, ˇP, t) − G1

(0, 0, t)

ˇG2

( ˇQ, ˇP, t) = G2

( ˇQ, ˇP, t) − G2

(0, 0, t) +

|n|,|¯n|≤N

∂(q,p)G1

n( ˇQ, ˇP) − ∂(q,p)G1

n(0, 0) α1,1

¯n,1

(1.18)

where

∆(n, ˇQ, ˇP) := [i n IC 2 − JD2

H( ˇQ, ˇP)] i n IC 2 − JD2

H(0, 0)

−1

α1,1

n,1 = i n IC 2 − JD2

H(0, 0)

−1

F1

n(0, 0, 0)

α1,1

n,2 = [i n IC d − A]

−1

G1

n(0, 0).

(1.19)

2The letter H must be read as ”upper eta”

3for the application in chapter 4 it suffices to consider the expansions including terms of order O(ε2) of ˇF and of order

O(ε) of ˇG. The formulae for O(ε3)–terms are provided in order to enable a more detailed discussion on the capture in

resonance, cf. section 2.3.5.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-22-320.jpg)

![1.2. The Periodic Solution 9

• Moreover, ˇF1

, ˇF2

, ˇG1

and ˇG2

may be represented as Fourier polynomials in t, similar to the

representation (1.4), i.e.

ˇFj

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) =

|n|≤jN

ˇFj

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) eint ˇGj

( ˇQ, ˇP, t) =

|n|≤jN

ˇGj

n( ˇQ, ˇP, t) eint

(1.20)

• The values of the map ˇF3

may be expressed in an analogous way:

ˇF3

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) =F3

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t) −

|n|≤N

∆(n, ˇQ, ˇP) F3

n(0, 0, 0)eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

JD3

H( ˇQ, ˇP) α1,1

n,1, α2,1

¯n,1

+ ∂(q,p)F2

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂(q,p)F2

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

¯n,1

+ ∂ηF2

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂ηF2

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

¯n,1

+ ∂(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂(q,p)F1

n(0, 0, 0) α2,1

¯n,1

+ ∂ηF1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂ηF1

n(0, 0, 0) α2,1

¯n,1 ei(n+¯n)t

+

|n|,|¯n|,|˜n|≤N

JD3

H( ˇQ, ˇP) α1,1

n,1, α2,2

¯n,˜n,1

+ 1

6 JD4

H( ˇQ, ˇP) − ∆(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) JD4

H(0) α1,1

n,1 α1,1

¯n,1 α1,1

˜n,1

+ 1

2 ∂2

(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂2

(q,p)F1

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

¯n,1, α1,1

˜n,1

+ 1

2 ∂η∂(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂η∂(q,p)F1

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

˜n,1, α1,1

¯n,2

+ 1

2 ∂(q,p)∂ηF1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂(q,p)∂ηF1

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

˜n,2, α1,1

¯n,1

+ ∂(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂(q,p)F1

n (0, 0, 0) α2,2

¯n,˜n,1

+ ∂ηF1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂ηF1

n(0, 0, 0) α2,2

¯n,˜n,1 ei(n+¯n+˜n)t

.

(1.21)

where in addition

α2,1

n,1 = i n IC 2 − JD2

H(0, 0)

−1

F2

n(0, 0, 0) α2,1

n,2 = [i n IC d − A]

−1

G2

n(0, 0)

α2,2

n,¯n,1 = i (n + ¯n) IC 2 − JD2

H(0, 0)

−1

∂(q,p)F1

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

n,1 + ∂ηF1

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

n,2 .

PROOF: In order to simplify the notation, we use the same abbreviations as introduced in the proof of

lemma 1.2.2:

x := (q, p, η) ˇx(t, ε) :=(ˇq, ˇp, ˇη)(t, ε) y := ( ˇQ, ˇP, H)

f(x) :=

J∇H(q, p)

A η

g(x, t, ε) :=

F(q, p, η, t, ε)

G(q, p, t, ε)

(1.22)

such that system (1.1) defined for x ∈ R2+d

reads

˙x = f(x) + g(x, t, ε). (1.23)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-23-320.jpg)

![1.2. The Periodic Solution 11

1. Consider the Taylor expansion of ˜f at ε = 0, i.e. the representation

˜f(y, t, ε) = ˜f(y, t, 0) + ε ∂ε

˜f(y, t, 0) + 1

2 ε2

∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) + 1

6 ε3

∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) + ε4 ˜f4

(y, t, ε) (1.29)

where ˜f4

(y, t, ε) is of class Cω

(R2+d

× R × (−ε1, ε1), R2+d

) and 2π–periodic with respect to t.

Setting

ˇFj

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t)

ˇGj

( ˇQ, ˇP, t)

:= 1

j! ∂j

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) j = 1, 2, 3

ˇF4

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε)

ˇG4

( ˇQ, ˇP, t, ε)

:= ˜f4

(y, t, ε),

(1.30)

and taking into account that (1.26), (1.28) imply

ˇF(0, 0, 0, t, ε)

ˇG(0, 0, t, ε)

= −f(0) = 0

we find the first statement claimed to be proved at once.

2. In order to prove the second statement we note that by (1.28), (1.30)

ˇF( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε) = J ∇H(ˇq + ˇQ, ˇp + ˇP) − J ∇H( ˇQ, ˇP) − J∇H(ˇq, ˇp)

+ F(ˇq + ˇQ, ˇp + ˇP, ˇη + H, t, ε) − F(ˇq, ˇp, ˇη, t, ε)

such that the affinity of F assumed in GA 1.4 implies the affinity of ˇF ( with respect to H).

3. We determine the Taylor coefficients in (1.29).

Using (1.26) we have

∂j

ε

˜f(0, t, 0) = 0 j = 1, 2, 3. (1.31)

On the other hand, from definition (1.25) we derive

∂ε

˜f(y, t, ε) = Df(ˇx(t, ε) + y) ∂ε ˇx(t, ε) + ∂xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂εˇx(t, ε)

+ ∂εg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) − ∂ε ˙ˇx(t, ε),

(1.32)

∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, ε) = D2

f(ˇx(t, ε) + y) ∂εˇx(t, ε)[2]

+ Df(ˇx(t, ε) + y) ∂2

ε ˇx(t, ε)

+ ∂2

xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂εˇx(t, ε)[2]

+ ∂xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂2

ε ˇx(t, ε)

+ 2 ∂ε∂xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂εˇx(t, ε) + ∂2

ε g(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε)

− ∂2

ε

˙ˇx(t, ε)

(1.33)

∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, ε) = D3

f(ˇx(t, ε) + y) ∂ε ˇx(t, ε)[3]

+ 3 D2

f(ˇx(t, ε) + y) (∂ε ˇx(t, ε), ∂2

ε ˇx(t, ε)) + Df(ˇx(t, ε) + y) ∂3

ε ˇx(t, ε)

+ ∂3

xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂εˇx(t, ε)[3]

+ 3 ∂2

xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) (∂εˇx(t, ε), ∂2

ε ˇx(t, ε)) + ∂xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂3

ε ˇx(t, ε)

+ 3 ∂ε∂2

xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂εˇx(t, ε)[2]

+ 3 ∂2

ε ∂xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂ε ˇx(t, ε)

+ 3 ∂ε∂xg(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε) ∂2

ε ˇx(t, ε) + ∂3

ε g(ˇx(t, ε) + y, t, ε)

− ∂3

ε

˙ˇx(t, ε)

(1.34)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-25-320.jpg)

![12 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

where the notation v[j]

must be understood as applying the corresponding multilinear–form on the

j vectors (v, . . . , v). Taking into account that by (1.24)

∂j

xg(y, t, 0) = 0 j = 1, 2, 3 ∂ε∂j

xg(y, t, 0) = ∂j

xg1

(y, t) j = 0, 1, 2

∂2

ε ∂j

xg(y, t, 0) = 2 ∂j

xg2

(y, t) j = 0, 1 ∂3

ε g(y, t, 0) = 6 g3

(y, t),

we therefore see that setting ε = 0, (1.32), (1.33) and (1.34) reduce to

∂ε

˜f(y, t, 0) = Df(y) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0) + g1

(y, t) − ∂t∂ε ˇx(t, 0)

∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) = D2

f(y) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0)[2]

+ Df(y) ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0)

+ 2 ∂xg1

(y, t) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0) + 2 g2

(y, t) − ∂t∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0)

∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) = D3

f(y) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0)[3]

+ 6 D2

f(y) (∂ε ˇx(t, 0), 1

2 ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0)) + Df(y) ∂3

ε ˇx(t, 0)

+ 3 ∂2

xg1

(y, t) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0)[2]

+ 6 ∂xg2

(y, t) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0)

+ 6 ∂xg1

(y, t) 1

2 ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) + 6 g3

(y, t)

− ∂t∂3

ε ˇx(t, 0).

(1.35)

4. In a next step we compute the functions ∂ε ˇx(t, 0), ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) and ∂3

ε ˇx(t, 0) by solving differential

equations :

Recall that by GA 1.1a D3

H(0, 0) = 0 such that by definition of f, D2

f(0) = 0. Therefore (1.24)

together with (1.31), (1.35) yields the following linear inhomogeneous differential equations

∂t∂ε ˇx(t, 0) = Df(0) ∂εˇx(t, 0) + g1

(0, t) = Df(0) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0) +

|n|≤N

g1

n(0) eint

, (1.36)

∂t∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) = Df(0) ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) + 2 ∂xg1

(0, t) ∂εˇx(t, 0) + 2 g2

(0, t) (1.37)

and

∂t∂3

ε ˇx(t, 0) = Df(0) ∂3

ε ˇx(t, 0) + D3

f(0) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0)[3]

+ 3 ∂2

xg1

(0, t) ∂ε ˇx(t, 0)[2]

+ 6 ∂xg2

(0, t) ∂εˇx(t, 0)

+ 6 ∂xg1

(0, t) 1

2 ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) + 6 g3

(0, t).

(1.38)

As we have shown in (1.12) in the proof of lemma 1.2.2, σ (Df(0)) ∩ i Z = ∅. Hence lemma 1.2.3

may be applied to equation (1.36). Therefore the unique 2π–periodic solution ∂ε ˇx(t, 0) of (1.36)

is given by

∂ε ˇx(t, 0) =

|n|≤N

α1,1

n eint

, where α1,1

n := [i n IC 2+d − Df(0)]

−1

g1

n(0). (1.39)

Let us rewrite the differential equation (1.37) using (1.24) and (1.39):

∂t∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) = Df(0) ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) + 2

|n|≤N

Dg1

n(0)eint

|¯n|≤N

α1,1

¯n ei¯nt

+ 2

|n|≤N

g2

n(0) eint

= Df(0) ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) + 2

|n|≤N

g2

n(0) eint

+ 2

|n|,|¯n|≤N

Dg1

n(0) α1,1

¯n ei(n+¯n)t

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-26-320.jpg)

![1.2. The Periodic Solution 13

Solving this equation with the help of lemma 1.2.3 again we obtain

1

2 ∂2

ε ˇx(t, 0) =

|n|≤N

α2,1

n eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

α2,2

n,¯n ei(n+¯n)t

,

with α2,1

n := [i n IC 2+d − Df(0)]

−1

g2

n(0)

α2,2

n,¯n := [i (n + ¯n) IC 2+d − Df(0)]

−1

Dg1

n(0) α1,1

¯n .

(1.40)

Finally we proceed in an analogous way to obtain

1

6 ∂3

ε ˇx(t, 0) =

|n|,|¯n|,|˜n|≤N

α3,3

n,¯n,˜n ei(n+¯n+˜n)t

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

α3,2

n,¯n ei(n+¯n)t

+

|n|≤N

α3,1

n eint

(1.41)

where

α3,3

n,¯n,˜n = [i (n + ¯n + ˜n) IC 2+d − Df(0)]

−1 1

6 D3

f(0)(α1,1

n , α1,1

¯n , α1,1

˜n )

+ 1

2 D2

g1

n(0)(α1,1

¯n , α1,1

˜n ) + Dg1

n(0) α2,2

¯n,˜n

α3,2

n,¯n = [i (n + ¯n) IC 2+d − Df(0)]−1

Dg1

n(0)α2,1

¯n + Dg2

n(0)α1,1

¯n

α3,1

n = [i n IC 2+d − Df(0)]−1

g3

n(0).

(1.42)

5. In order to gain expressions for the coefficient maps ∂ε

˜f(y, t, 0), 1

2 ∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) and 1

6 ∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) in

terms of known quantities, we combine the results derived in the first two steps. Let us introduce

the notations

∆(n, ˇQ, ˇP) := [i n IC 2 − JD2

H( ˇQ, ˇP)] i n IC 2 − JD2

H(0, 0)

−1

M(n, ˇQ, ˇP) :=

∆(n, ˇQ, ˇP) 0

0 IC d

= [i n IC 2+d − Df(y)] [i n IC 2+d − Df(0)]

−1

.

(1.43)

Note that ∆(n, 0, 0) = IC 2 and M(n, 0, 0) = IC 2+d . Using the identities (1.24) and (1.39) we rewrite

the first equation in (1.35):

∂ε

˜f(y, t, 0) =

|n|≤N

Df(y) α1,1

n + g1

n(y) − i n α1,1

n eint

=

|n|≤N

g1

n(y) − [i n IC 2+d − Df(y)] α1,1

n eint

=

|n|≤N

g1

n(y) − M(n, ˇQ, ˇP) g1

n(0) eint

. (1.44)

The analogous result for 1

2 ∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) is achieved by substituting (1.24), (1.40) into the second](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-27-320.jpg)

![14 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

equation of (1.35):

1

2 ∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) = 1

2 D2

f(y)

|n|≤N

α1,1

n eint

,

|¯n|≤N

α1,1

¯n ei¯nt

+

|n|≤N

Df(y) α2,1

n eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

Df(y) α2,2

n,¯n ei(n+¯n)t

+

|n|≤N

Dg1

n(y) eint

|¯n|≤N

α1,1

¯n ei¯nt

+

|n|≤N

g2

n(y)eint

−

|n|≤N

i n α2,1

n eint

−

|n|,|¯n|≤N

i (n + ¯n) α2,2

n,¯n ei(n+¯n)t

=

|n|≤N

Df(y) α2,1

n + g2

n(y) − i n α2,1

n eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

1

2 D2

f(y) α1,1

n , α1,1

¯n + Df(y) α2,2

n,¯n + Dg1

n(y) α1,1

¯n

−i (n + ¯n) α2,2

n,¯n ei(n+¯n)t

.

Using the abbreviations defined in (1.43) together with the definitions of α2,1

n , α2,2

n,¯n given in (1.40)

we find

1

2 ∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) =

|n|≤N

g2

n(y) − [i n IC 2+d − Df(y)] α2,1

n eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

1

2 D2

f(y) α1,1

n , α1,1

¯n + Dg1

n(y) α1,1

¯n

− [i (n + ¯n) IC 2+d − Df(y)] α2,2

n,¯n ei(n+¯n)t

=

|n|≤N

g2

n(y) − [i n IC 2+d − Df(y)] [i n IC 2+d − Df(0)]

−1

g2

n(0) eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

1

2 D2

f(y) α1,1

n , α1,1

¯n + Dg1

n(y) α1,1

¯n

− [i (n + ¯n) IC 2+d − Df(y)] [i (n + ¯n) IC 2+d − Df(0)]

−1

Dg1

n(0) α1,1

¯n ei(n+¯n)t

hence

1

2 ∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) =

|n|≤N

g2

n(y) − M(n, ˇQ, ˇP) g2

n(0) eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

1

2 D2

f(y) α1,1

n , α1,1

¯n + Dg1

n(y) − M(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP)Dg1

n(0) α1,1

¯n ei(n+¯n)t

. (1.45)

In a similar way we deduce the following representation of 1

6 ∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) from (1.24), (1.41) and the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-28-320.jpg)

![16 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

which by (1.40), (1.42) eventually leads to

1

6 ∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) =

|n|≤N

g3

n(y) − M(n, ˇQ, ˇP) g3

n(0) eint

+

|n|,|¯n|≤N

D2

f(y) α1,1

n , α2,1

¯n + Dg2

n(y) − M(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) Dg2

n(0) α1,1

¯n

+ Dg1

n(y) − M(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP)Dg1

n(0) α2,1

¯n ei(n+¯n)t

+

|n|,|¯n|,|˜n|≤N

D2

f(y) α1,1

n , α2,2

¯n,˜n

+ 1

6 D3

f(y) − M(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) D3

f(0) α1,1

n , α1,1

¯n , α1,1

˜n

+ 1

2 D2

g1

n(y) − M(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) D2

g1

n(0) α1,1

¯n , α1,1

˜n

+ Dg1

n(y) − M(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) Dg1

n(0) α2,2

¯n,˜n) ei(n+¯n+˜n)t

.

(1.46)

6. In a next step, we split the quantities ∂ε

˜f(y, t, 0), 1

2 ∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) and 1

6 ∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) into two compo-

nents, expressed in terms of the maps Fj

n and Gj

n. This will lead us to the formulae claimed in

(1.18) and (1.21).

Using definitions (1.43), (1.24) we rewrite (1.44) as follows :

∂ε

˜f(y, t, 0) =

|n|≤N

F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n, ˇQ, ˇP) F1

n (0, 0, 0)

G1

n( ˇQ, ˇP) − G1

n(0, 0)

eint

. (1.47)

For convenience we split the vectors αj,1

n , α2,2

n,¯n into two components of dimension 2 and d :

αj,1

n =:

αj,1

n,1

αj,1

n,2

α2,2

n,¯n =:

α2,2

n,¯n,1

α2,2

n,¯n,2

By definition (1.22) we find derivatives of f to be diagonal operators in the following sense :

Df(y) ∼=

JD2

H( ˇQ, ˇP) 0

0 A

D2

f(y)

( ˇQ1, ˇP1)

H1

( ˇQ2, ˇP2)

H2

=

JD3

H( ˇQ, ˇP)( ˇQ1, ˇP1)( ˇQ2, ˇP2)

0

(1.48)

D3

f(y)

( ˇQ1, ˇP1)

H1

( ˇQ2, ˇP2)

H2

( ˇQ3, ˇP3)

H3

=

JD4

H( ˇQ, ˇP)( ˇQ1, ˇP1)( ˇQ2, ˇP2)( ˇQ3, ˇP3)

0

.

Note that by simple consequence,

[i n IC 2+d − Df(y)] =

i n IC 2 − JD2

H( ˇQ, ˇP) 0

0 i n IC d − A

.

Together with the representation of α1,1

n introduced above, we obtain

D2

f(y) α1,1

n , αk,j

¯n =

JD3

H( ˇQ, ˇP) α1,1

n,1, αk,j

¯n,1

0

k, j = 1, 2, (1.49)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-30-320.jpg)

![18 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

+

|n|,|¯n|,|˜n|≤N

JD3

H( ˇQ, ˇP) α1,1

n,1, α2,2

¯n,˜n,1

0

+1

6

JD4

H( ˇQ, ˇP) − ∆(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) JD4

H(0) α1,1

n,1 α1,1

¯n,1 α1,1

˜n,1

0

+1

2

∂2

(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂2

(q,p)F1

n(0, 0, 0) α1,1

¯n,1, α1,1

˜n,1

∂2

(q,p)G1

n( ˇQ, ˇP) − ∂2

(q,p)G1

n(0, 0) α1,1

¯n,1, α1,1

˜n,1

+1

2

∂η∂(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂η∂(q,p)F1

n (0, 0, 0) α1,1

˜n,1, α1,1

¯n,2

0

+1

2

∂(q,p)∂ηF1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n + ˜n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂(q,p)∂ηF1

n (0, 0, 0) α1,1

˜n,2, α1,1

¯n,1

0

+

∂(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂(q,p)F1

n(0, 0, 0) α2,2

¯n,˜n,1

∂(q,p)G1

n( ˇQ, ˇP) − ∂(q,p)G1

n(0, 0) α2,2

¯n,˜n,2

+

∂ηF1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) − ∆(n + ¯n, ˇQ, ˇP) ∂ηF1

n (0, 0, 0) α2,2

¯n,˜n,1

0

ei(n+¯n+˜n)t

.

7. Summarizing the identities given in (1.25), (1.29) and (1.27) we consider the transformed system

˙y = ˜f(y, t, ε) = f(y) + ε∂ε

˜f(y, t, 0) + 1

2 ε2

∂2

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) + 1

6 ε3

∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, 0) + ε4 ˜f4

(y, t, ε)

which by (1.22), (1.30) may be represented in the form

( ˙ˇQ, ˙ˇP)

˙H

=

J∇H( ˇQ, ˇP)

A H

+

3

j=1

εj

ˇFj

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t)

ˇGj

( ˇQ, ˇP, t)

+ ε4

ˇF4

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t, ε)

ˇG4

( ˇQ, ˇP, t, ε)

.

Thus the identities (1.18) hold as it has been established in (1.47), (1.51) respectively.

8. In order to obtain the formula given in (1.21) one has to consider the first two components of

1

6 ∂3

ε

˜f(y, t, 0), which by (1.30) represents the vector–valued map ˇF3

( ˇQ, ˇP, H, t).

9. It remains to prove the formulae given for the quantities α1,1

n,1, α1,1

n,2 etc. :

From the definition of (1.24) of gj

n(y) we have

gj

n(0) =

Fj

n(0, 0, 0)

Gj

n(0, 0)

j = 1, 2, 3

hence, by definitions (1.39), (1.40) of the vectors αj,1

n ,

αj,1

n =

i n IC 2 − JD2

H(0, 0)

−1

Fj

n(0, 0, 0)

[i n IC d − A]

−1

Gj

n(0, 0)

j = 1, 2.

Together with (1.50) this implies

Dg1

n(y) α1,1

¯n =

∂(q,p)F1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) α1,1

¯n,1 + ∂ηF1

n( ˇQ, ˇP, H) α1,1

¯n,2

∂(q,p)G1

n( ˇQ, ˇP) α1,1

¯n,1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-32-320.jpg)

![1.2. The Periodic Solution 19

such that definition (1.40) reads

α2,2

n,¯n =

i (n + ¯n) IC 2 − JD2

H(0, 0)

−1

∂(q,p)F1

n (0, 0, 0) α1,1

n,1 + ∂ηF1

n (0, 0, 0) α1,1

n,2

[i (n + ¯n) IC d − A]

−1

∂(q,p)G1

n(0, 0) α1,1

n,1

.

We therefore have established all assertions made in proposition 1.2.4.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-33-320.jpg)

![20 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

1.3 Some Illustrative Examples

As explained in section 1.1.3, the strategy of this chapter consists in proving the existence of a local,

attractive, two–dimensional invariant manifold. Once this step has been accomplished the qualitative

discussion of (1.1) is reduced to the discussion of a plane, non–autonomous system by considering the

system restricted to the attractive invariant manifold.

However there are a few points to be made when entering this line of attack. The majority of the results

on the existence of attractive invariant manifolds are based on the discussion of Lyapunov type numbers

of solutions, hence set in a more abstract framework4

rather than an applicable form. For the purpose

of this work an approach where assumptions are made on known quantities (as the vector field) is more

convenient.

The general setting for this case can be found in a result by Kirchgraber [9]. It supplies the existence

and additional properties of an attractive invariant manifold for mappings without giving smoothness,

however. In this work we will apply an adaption by Nipp / Stoffer [13] which deals with ODE’s and

establishes smoothness as well. The assumptions on the system made by Nipp / Stoffer are expressed

using certain Lipschitz numbers of the vector field and logarithmic norms of derivatives of the vector

field.

However, we must take into account that theLipschitz numbers of the vector field as well as the logarithmic

norms of the derivatives depend on the choice of coordinates. Hence it is of great interest to find

appropriate coordinates in order to obtain satisfactory results.

Thus the difficulties in discussing the assumptions on the Lyapunov type numbers necessary for the more

”abstract approach” are replaced by the problem of defining suitable coordinates, when aiming at the

setup made in [9] and [13]. The following example illustrates how the choice of ”unnatural” coordinates

may restrict the results obtained in an unsatisfactory way.

1.3.1 Example 1 (disadvantegous cartesian coordinates)

Consider the (unperturbed) system (1.16) in the case of H( ˇQ, ˇP) = ˇP2

/2 − cos( ˇQ) of the mathematical

pendulum,

˙ˇQ = ˇP

˙ˇP = − sin( ˇQ)

˙H = A H,

(1.55)

where A < 0. One of the assumptions made in Nipp / Stoffer [13] includes the existence of constants

γ1 ∈ R, γ2 > 0 such that

µ −JD2

H( ˇQ, ˇP) ≤ γ1, µ (A) ≤ −γ2, γ1 < γ2, (1.56)

uniformly, where µ (M) denotes the logarithmic norm of a matrix M (cf. definition 1.4.5). Choosing the

euclidean norm on R2

one has

µ −JD2

H( ˇQ, ˇP) = 1

2 1 − cos( ˇQ) µ (A) = A,

4as, for instance, given in [4], [6]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-34-320.jpg)

![1.3. Some Illustrative Examples 23

is invariant with respect to (1.59), the transformation

( ˇQ, ˇP) = (−εH, εH) + (Q, P) (1.64)

may be performed, yielding the system

˙Q = P + εP (P + ε H)

˙P = −Q

˙H = −H.

(1.65)

Here the right hand side of the ( ˙Q, ˙P)–equation vanishes for (Q, P) = (0, 0), hence the H–axis is invariant

with respect to (1.65). Applying (1.61) on (1.65) then yields

˙ϕ = 1 + ε cos2

(ϕ) (P(h) cos(ϕ) + ε H)

˙h = ε P(h)

d

dh P(h)

sin(ϕ) cos(ϕ) (P(h) cos(ϕ) + ε H)

˙H = −H.

(1.66)

Following the properties of P assumed in 1.97 a, this system admits a Cr+5

–extension into h = 0.

1.3.4 Example 4 (reasons to introduce the map P)

Let us rewrite transformation (1.61) of example 3 for P(h) =

√

2 h :

( ˇQ, ˇP) =

√

2 h

sin(ϕ)

cos(ϕ)

The solution (q, p)(t; 0,

√

2 h) with initial value (0,

√

2 h) at time t = 0 of the corresponding Hamiltonian

system satisfies H((q, p)(t; 0,

√

2 h)) = h for all t ∈ R. Hence for this choice of P, the action variable h

may be viewed as the ”energy” of the solutions. Although these action angle coordinates appear to be

suitable, the corresponding system is not differentiable in h = 0 :

˙ϕ = 1 + ε cos2

(ϕ)

√

2 h cos(ϕ) + ε H

˙h = ε h sin(ϕ) cos(ϕ)

√

2 h cos(ϕ) + ε H

˙H = −H.

In order to extend the corresponding system in action angle coordinates into h = 0 in a sufficient regular

way, assumption 1.97 b on the map P therefore is essential.

Additionally we will see in what follows, that the region of the phase space on which the result given in

[13] may be applied to, must be invariant. Due to this assumption, it may be necessary to introduce a

”cutting function” in order to change the vector field locally, if dealing with regions having non-invariant

boundaries. This may be achieved by choosing P in a suitable way. However, inside the regions (on

any compact subset) P may be taken as the identity P(h) = h. In the case 0 ∈ J we will see that the

set {h = 0} is invariant with respect to the corresponding system. Hence in this situation P(h) = h is

admissible even for small h ≥ 0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-37-320.jpg)

![1.4. The Strongly Stable Manifold of the Equilibrium Point 25

1.4.1 The Existence of the Strongly Stable Manifold

In this first subsection we will state the existence of the strongly stable manifold of system (1.16) for

small parameters ε. The theory found in various contributions (see [8], [10]), which may be applied to

establish the existence of a strongly stable manifold deals with the special case where the linearization of

the perturbation vanishes at the origin.

Thus we are not in the position to apply these results directly5

. However it is possible to modify the

program carried out in [8] in a way such that the statements needed here may be established. We therefore

will not verify all details but confine ourselves with a sketch of the adapted proof strategy.

The main idea to proceed in the more general case where the linearization of the perturbation does not

vanish at the origin consist in writing the map V using a linear map Vλ in the form

V(t, H, ε) := λ Vλ(t, ε/λ2

, H) H (1.67)

where the existence of Vλ is obtained by a contraction mapping argument and λ is a sufficiently small,

fixed parameter. This will be demonstrated in the proof of the following proposition :

Proposition 1.4.1 Given any ̺ > 0 there exists an ε2 = ε2(r, ̺) as well as a map V defined for t ∈ R,

|H| < ̺, |ε| ≤ ε2 with values in R2

and of class Cr+7

(where all derivatives up to order r+7 are uniformly

bounded by 1) such that the graph

Nε := (t, ( ˇQ, ˇP), H) ∈ R × R2

× Rd

( ˇQ, ˇP) = V(t, H, ε), |H| < ̺ (1.68)

is an invariant set of (1.16). Moreover the map V satisfies the following properties :

1. V(t, 0, ε) = 0

2. V(t, H, 0) = 0

3. V is 2π–periodic with respect to t.

The proof of this proposition is carried out in several steps.

• The first step consist in simplifying the notation as follows : Given any fixed 0 < λ < 1 we set

(x, y) := (H, ( ˇQ, ˇP))

ϑ := (t, ǫ) := (t, ε/λ2

).

(1.69)

Using these abbreviations we will rewrite system (1.16) in autonomous form. The independent

variable will be denoted by s and differentiation with respect to s is marked by a dot again (i.e. ˙ϑ).

• Lemma 1.4.2 There exist maps X0, Y0, Y1 and Y2 defined for t ∈ R, |ǫ| < ε1, |x| < ̺ and y ∈ R2

as well as a matrix B ∈ R2×2

such that (1.16) is equivalent to the (autonomous) system

˙ϑ = a

˙x = A x + λ2

X0(ϑ, y; λ) y

˙y = B y + λ2

Y0(ϑ, y; λ) x + λ2

Y1(ϑ, y; λ) y + Y2(y)(y, y)

(1.70)

5The author of this thesis did not find a way to reproduce an estimate analogous to equation (32) in [8] for the situation

discussed there in section 6, i.e. the perturbed case. (For an illustrative example, consider the system ˙x = −x+ε y, ˙y = ε x.)

This eventually gave rise to the modification introduced here.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-39-320.jpg)

![1.4. The Strongly Stable Manifold of the Equilibrium Point 27

• In a next step we define an appropriate space for the maps V used in the ansatz (1.67) :

Definition 1.4.3 Let Xj

denote the following subspace of Cj

–maps taking values in the space

L(Rd

, R2

) of d × 2–matrices :

Xj

:= V ∈ Cj

(R × (−ε1, ε1) × Rd

, L(Rd

, R2

)) V satisfies (1.73 a)–(1.73 c) , (1.72)

where

1.73 a. V is ω–periodic with respect to ϑ

1.73 b. V (ϑ, x) = 0 if ϑ = (t, 0)

1.73 c. V X j < ∞ with V X j := max

α∈N 2+d

0≤|α|≤j

sup

t∈R

|ǫ|≤ε1

sup

|x|<̺

∂ α

(ϑ,x)V (ϑ, x) .

Note that for any multi–index α ∈ N2+d

, |α| := α1 + · · ·+ α2+d and ∂ α

(ϑ,x) := ∂ α1

t ∂ α2

ǫ ∂ α3

x1

. . . ∂

α2+d

xd .

Then (Xj

, . X j ) is a Banach space.

• For any V ∈ Xr+7

we substitute y = λ V (ϑ, x) x into the perturbation terms of (1.70), i.e. consider

the systems

˙ϑ = a

˙x = A x + λ3

X0(ϑ, λ V (ϑ, x) x; λ) V (ϑ, x) x

(1.74)

and

˙y = B y + λ2

Y0(ϑ, λ V (ϑ, x) x; λ) x + λ3

Y1(ϑ, λ V (ϑ, x) x; λ) V (ϑ, x) x

+ λ2

Y2(λ V (ϑ, x) x)(V (ϑ, x) x, V (ϑ, x) x).

(1.75)

Let (ϑ, x)(s) := (ϑ, x)(s; ϑ0, x0; V ) denote the solution of (1.74) with initial value (ϑ0, x0) at time

s = 0 (where ϑ0 := (t0, ε0)) depending on V . We then will show that there exists a Vλ ∈ Xr+7

,

such that

y(s) := λ Vλ((ϑ, x)(s; ϑ0, x0; Vλ))) x(s)

is a solution of (1.75) for V = Vλ. This, however implies immediately that (ϑ, x, y)(s) is a solution

of (1.70). We will establish the existence of such a Vλ in an analogous way to the process given in

[8]. In particular the rescalation parameter λ is necessary to obtain sufficient regularity.

• For any fixed V ∈ BX r+8 (1) where

BX r+8 (1) := V ∈ Xr+8

V X r+8 ≤ 1

the following lemma presents a result on the fundamental solutions associated with (1.74):

Lemma 1.4.4 For any initial value (ϑ0, x0) and any V ∈ BX r+8 (1) let U(s) = U(s; ϑ0, x0; V )

denote the unique solution of

˙U(s) = A + λ3

X0(ϑ(s), λ V (ϑ(s), x(s)) x(s); λ) V (ϑ(s), x(s)) U(s) (1.76)

satisfying U(0) = IRd . Then x(s; ϑ0, x0; V ) = U(s; ϑ0, x0; V ) x0.

Moreover there exists λ1 > 0 and a polynomial π(s) with positive coefficients such that for 0 < λ <

λ1 and |x0| < ̺,

|U(s; ϑ0, x0; V )| ≤ e−

c0

2 s

∂ α

(ϑ0,x0)U(s; ϑ0, x0; V ) ≤ e−

c0

2 s

λ3

π(s) 0 < |α| ≤ r + 8.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-41-320.jpg)

![28 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

This lemma 1.4.4 is proved by induction with respect to the length |α| of the multi–index α. The

induction is carried out using the notion of the logarithmic norm (introduced in the following

definition 1.4.5) and the statement given in lemma 1.4.6 :

Definition 1.4.5 Following Stroem [18] we introduce the so–called logarithmic norm of a matrix

M ∈ Rn×n

by

µ (M) := lim

δ→0+

|IRn + δ M| − 1

δ

,

where |.| denotes the matrix norm based on the norm chosen on Rn

.

As a simple consequence of lemma 2 in [18] we find

Lemma 1.4.6 Consider a solution W(s) of the inhomogenous, non–autonomous linear differential

equation

˙W(s) = M(s) W(s) + N(s)

where M(s), N(s) are time–dependent linear operators on Rd

, the logarithmic norm µ(M(s)) is

uniformly bounded by −c0

2 and |N(s)| ≤ λ3

e−

c0

2 s

˜π(s) (˜π is a polynomial with positive coefficients).

Then

|W(s)| ≤ e−

c0

2 s

|W(0)| + λ3

π(s) s ≥ 0.

where π(s) =

s

0

˜π(t) dt has positive coefficients as well.

• As mentioned above, the existence of a map Vλ defining an invariant manifold (see (1.67), (1.68))

is established using the contraction mapping theorem. The definition of the mapping considered

and the proof of its contracting properties are the subject of the next step in this line:

Lemma 1.4.7 There exists a λ2 := λ2(r, ̺) > 0 such that for every V ∈ BX r+8 (1), 0 < λ < λ2,

the image T V of the map T , given by

T V (ϑ0, x0) = − 1

λ

∞

0

e−sB

λ2

Y0(ϑ, λ V (ϑ, x) x; λ) U

+ λ3

Y1(ϑ, λ V (ϑ, x) x; λ) V (ϑ, x) U

+ λ2

Y2(λ V (ϑ, x) x)(V (ϑ, x) x, V (ϑ, x) U) ds

(1.77)

exists. Recall that (ϑ, x)(s) = (ϑ, x)(s; ϑ0, x0; V ), U(s) = U(s; ϑ0, x0; V ) denote solutions of (1.74),

(1.76) respectively.

Moreover, the map T is a contraction from BX r+8 (1) to BX r+8 (1) with respect to the Xr+7

–topology

induced on Xr+8

, i.e.

1.78 a. T V ∈ BX r+8 (1)

1.78 b. T V1 − T V2 X r+7 ≤ 1

2 V1 − V2 X r+7 for all V1, V2 in BX r+8 (1).

The way followed to establish this statement is similar to the one given in [8], p. 558–561. The

estimates found in lemma 1.4.4 are used repeatedly. Furthermore one has to apply lemma 1.4.6 to

derive the scalar bounds for ∂ α

(ϑ,x)T V , ∂ α

(ϑ,x) (T V1 − T V2), respectively.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-42-320.jpg)

![32 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

and more explicitely

ˆF1

(Q, P, H, t) = J D2

H(Q, P) − D2

H(0, 0) V1

(t) H

+ ˇF1

(Q, P, H, t) − ˇF1

(0, 0, H, t)

ˆF2

(Q, P, H, t) = J D2

H(Q, P) − D2

H(0, 0) V2

(t, H) H

+ 1

2 JD3

H(Q, P)(V1

(t)H)[2]

+ ˇF2

(Q, P, H, t) − ˇF2

(0, 0, H, t)

+ ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇF1

(Q, P, H, t) − ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇF1

(0, 0, H, t) V1

(t) H

− V1

(t) ˇG1

(Q, P, t)

(1.90)

as well as

ˆG1

(Q, P, H, t) = ˇG1

(Q, P, t)

ˆG2

(Q, P, H, t) = ˇG2

(Q, P, t) + ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇG1

(Q, P, t) V1

(t) H.

(1.91)

• The map ˆF3

may be written in the form

ˆF3

(Q, P, H, t) = ˇF3

(Q, P, 0, t) − ˇF3

(0, 0, 0, t)

− V1

(t) ˇG2

(Q, P, t) − ˇG2

(0, 0, t) + ˆF3,1

(Q, P, H, t)H

(1.92)

for a suitable map ˆF3,1

: R2

× Rd

× R → L(Rd

, R2

).

• Finally, ˆF1

, ˆF2

, ˆG1

and ˆG2

may be represented as Fourier polynomials in t, i.e.

ˆFj

(Q, P, H, t) =

|n|≤jN

ˆFj

n(Q, P, H, t) eint ˆGj

(Q, P, H, t) =

|n|≤jN

ˆGj

n(Q, P, H, t) eint

.

(1.93)

Note that although we write H in the arguments of ˆG1

in (1.89) for simplicity, this map does not depend

on H.

PROOF: Taking the time derivative of transformation (1.86) and using (1.16) we find

( ˙Q, ˙P) = J∇H((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε)) + ˇF((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε), H, t, ε)

−∂tV(t, H, ε) − ∂HV(t, H, ε) A H + ˇG((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε), t, ε) .

which together with the identity found for ∂tV(t, H, ε) in remark 1.4.8 yields

( ˙Q, ˙P) = J∇H((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε)) − J∇H(V(t, H, ε))

+ ˇF((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε), H, t, ε) − ˇF(V(t, H, ε), H, t, ε)

−∂HV(t, H, ε) ˇG((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε), t, ε) − ˇG(V(t, H, ε), t, ε) .

Setting

ˆF(Q, P, H, t, ε) := J∇H((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε)) − J∇H(V(t, H, ε)) − J∇H(Q, P)

+ ˇF((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε), H, t, ε) − ˇF(V(t, H, ε), H, t, ε)

− ∂HV(t, H, ε) ˇG((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε), t, ε) − ˇG(V(t, H, ε), t, ε)

(1.94)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-46-320.jpg)

![1.4. The Strongly Stable Manifold of the Equilibrium Point 33

we find ˆF to be of class Cr+7

(since V ∈ Cr+7

) and

( ˙Q, ˙P) = J∇H(Q, P) + ˆF(Q, P, H, t, ε).

Expanding ˆF with respect to V(t, H, ε) yields

ˆF(Q, P, H, t, ε) = JD2

H(Q, P) − JD2

H(0, 0) V(t, H, ε)

+1

2 JD3

H(Q, P) − JD3

H(0, 0) V(t, H, ε)[2]

+O(V(t, H, ε)[3]

)

+ ˇF(Q, P, H, t, ε) − ˇF(0, 0, H, t, ε)

+ ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇF(Q, P, H, t, ε) − ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇF(0, 0, H, t, ε) V(t, H, ε)

+1

2 ∂2

( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇF(Q, P, H, t, ε) − ∂2

( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇF(0, 0, H, t, ε) V(t, H, ε)[2]

+O(V(t, H, ε)[3]

)

−∂HV(t, H, ε) ˇG(Q, P, t, ε) − ˇG(0, 0, t, ε)

+ ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇG(Q, P, t, ε) − ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇG(0, 0, t, ε) V(t, H, ε)

+1

2 ∂2

( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇG(Q, P, t, ε) − ∂2

( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇG(0, 0, t, ε) V(t, H, ε)[2]

+O(V(t, H, ε)[3]

) .

Plugging in the expansion of V(t, H, ε) as given in (1.80), i.e.

V(t, H, ε) = ε V1

(t)H + ε2

V2

(t, H) H + ε3

V3

(t, H, ε),

we conclude

ˆF(Q, P, H, t, ε) = ε JD2

H(Q, P) − JD2

H(0, 0) V1

(t) H

+ ˇF1

(Q, P, H, t) − ˇF1

(0, 0, H, t)

+ε2

JD2

H(Q, P) − JD2

H(0, 0) V2

(t, H) H

+1

2 JD3

H(Q, P) − JD3

H(0, 0) V1

(t) H

[2]

+ ˇF2

(Q, P, H, t) − ˇF2

(0, 0, H, t)

+ ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇF1

(Q, P, H, t) − ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇF1

(0, 0, H, t) V1

(t) H

−V1

(t) ˇG1

(Q, P, t) − ˇG1

(0, 0, t)

+ε3 ˇF3

(Q, P, 0, t) − ˇF3

(0, 0, 0, t) − V1

(t) ˇG2

(Q, P, t) − ˇG2

(0, 0, t)

+ε3

O(H) + O(ε4

).

(Take into account that the terms included in O(V(t, H, ε)[3]

) are of order ε3

or higher and vanish for

H = 0).

Since D3

H(0, 0) = 0, ˇF3

(0, 0, 0, t) = 0 (cf. GA 1.1b, proposition 1.2.4) the formulae (1.90), (1.92) given

in the claim are established. The representation of ˆG(Q, P, H, t, ε) is found in an easier way :

˙H = A H + ˇG( ˇQ, ˇP, t, ε)

= A H + ˇG((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε), t, ε).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-47-320.jpg)

![34 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

Define ˆG(Q, P, H, t, ε) := ˇG((Q, P) + V(t, H, ε), t, ε), then ˆG ∈ Cr+7

, ˙H = A H + ˆG(Q, P, H, t, ε) and

ˆG(Q, P, H, t, ε) = ˇG(Q, P, t, ε) + ∂( ˇQ, ˇP)

ˇG(Q, P, t, ε)V(t, H, ε)

+1

2 ∂2

( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇG(Q, P, t, ε)V(t, H, ε)[2]

+ O(V(t, H, ε)[3]

)

= ε ˇG1

(Q, P, t) + ε2 ˇG2

(Q, P, t) + ∂( ˇQ, ˇP )

ˇG1

(Q, P, t) V1

(t)H + O(ε3

)

which corresponds to (1.91).

The last statement of proposition 1.4.9 is obtained by plugging (1.93) and (1.83) into the representations

(1.90), (1.91) respectively.

Note that since we have used the non–autonomous representation (1.16), the independent variable cor-

responds to t again. Hence ˙Q etc. denote the derivatives with respect to t.

Remark 1.4.10 It may be readily seen that if substituting F, G by ˆF, ˆG system (1.87) fulfills the

assumptions made in GA 1.1–GA 1.3. By consequence of the transformations carried out the identities

(1.88) hold and the vector fields ˆF, ˆG are of class Cr+7

.

In the next section we will consider systems of this type in general and introduce action angle coordinates.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-48-320.jpg)

![36 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

Using the solutions (q, p)(t; q0, p0) of the Hamiltonian system (1.2) we introduce a map Φ as follows:

Definition 1.5.1 Consider the maps Ω and P as in GA 1.1b, 1.97 a. We define the following quantities:

1. For any ϕ, h ∈ R let (˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0) := (q, p)( ϕ

Ω(p0) ; 0, p0) and set

Φ(ϕ, h) := (˜q, ˜p)(ϕ, P(h)). (1.98)

2. In order to shorten the notation we introduce the map

ω(h) := Ω(P(h)). (1.99)

The first lemma in this section gives a summary of a few properties of the map Φ.

Lemma 1.5.2 The following statements on the maps Ω, Φ are true:

1. The map Φ is of class Cω

(R2

, R2

) and 2π–periodic with respect to ϕ ∈ R.

2. If 0 ∈ J then

Φ(ϕ, 0) = 0. (1.100)

3. Let Ω0 denote the quantity introduced in GA 1.1a. Then

Ω(0) = Ω0. (1.101)

4. For all (ϕ, h) ∈ R2

the Jacobian determinant of Φ satisfies

det D Φ(ϕ, h) = ω(h)−1 d

dh H(0, P(h)). (1.102)

For 0 ∈ J this determinant tends towards zero, i.e. det D Φ(ϕ, h) → 0 as h → 0.

PROOF: The first two statements are simple consequences of GA 1.1 and 1.97 a together with the

definition of Φ. We therefore content ourselves with the proof of assertions 3 and 4.

In order to establish (1.101), let us rescale the (q, p)–coordinates of system (1.2) with a parameter λ > 0:

(q, p) = (λ¯q, λ¯p).

We rewrite the right hand side of system (1.2) in the form of a Taylor polynomial using the integral

formula for the remainder term which in addition with ∇H(0, 0) = 0 yields the expression

˙¯q

˙¯p

= JD2

H(0, 0)

¯q

¯p

+ λ

1

0

(1 − σ) J D3

H(σλ¯q, σλ¯p)(¯q, ¯p)[2]

dσ. (1.103)

Let (¯q, ¯p)(t; 0, ¯p0, λ) denote the solution of (1.103) with initial value (0, ¯p0) at time t = 0, where λ may

take any real value. Consider any p0 ∈ J . Then the function (q, p)(t; 0, λ ¯p0) is a solution of (1.2), with](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-50-320.jpg)

![1.5. The Action Angle Coordinates 41

Omitting the argument t − t(0) of ϕ, h, Q, P and H it suffices to show that

F2(t, ϕ, h, H, ε)

F3(t, ϕ, h, H, ε)

= [DΦ(ϕ, h)]

−1

J∇H(Q, P) + ˆF(Q, P, H, t, ε) , (1.113)

as this implies the first claim at once. Since DΦ(ϕ, h) ∈ R2×2

we find

[DΦ(ϕ, h)]

−1

= (det DΦ(ϕ, h))

−1

d

dh ˜p(ϕ, P(h)) − d

dh ˜q(ϕ, P(h))

−∂ϕ ˜p(ϕ, P(h)) ∂ϕ ˜q(ϕ, P(h))

.

Applying (1.102) and (1.105) we find

[DΦ(ϕ, h)]

−1

= ω(h)

d

dh H(0,P(h))

d

dh ˜p(ϕ, P(h)) − d

dh ˜q(ϕ, P(h))

ω(h)−1

∂qH(Φ(ϕ, h)) ω(h)−1

∂pH(Φ(ϕ, h))

= ω(h)

d

dh H(0,P(h))

(J∂hΦ(ϕ, h))T

ω(h)−1

(∇H(Φ(ϕ, h)))T

.

Hence for the first component of (1.113) we have to prove

F2(t, ϕ, h, H, ε) = ω(h)

d

dh H(0,P(h))

J∂hΦ(ϕ, h)| J∇H(Φ(ϕ, h)) + ˆF(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε)

= ω(h)

d

dh H(0,P(h))

(∂hΦ(ϕ, h)| ∇H(Φ(ϕ, h)))

+ ω(h)

d

dh H(0,P(h))

J∂hΦ(ϕ, h)| ˆF(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) .

Together with the identity (1.107), thus

d

dh H(0, P(h)) = d

dh H(Φ(ϕ, h)) = (∂hΦ(ϕ, h)| ∇H(Φ(ϕ, h)))

this turns out to be equivalent to

F2(t, ϕ, h, H, ε) = ω(h) + ω(h)

d

dh H(0,P(h))

J∂hΦ(ϕ, h)| ˆF(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) ,

which coincides with the definition of F2 given in (1.110). In much the similar way, for the second

component of (1.113) we have to establish

F3(t, ϕ, h, H, ε) = 1

d

dh H(0,P(h))

(∇H(Φ(ϕ, h))| J∇H(Φ(ϕ, h)))

+ 1

d

dh H(0,P(h))

∇H(Φ(ϕ, h))| ˆF(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε)

= 1

d

dh H(0,P(h))

∇H(Φ(ϕ, h))| ˆF(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) .

This holds again by (1.110).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-55-320.jpg)

![1.5. The Action Angle Coordinates 43

The mappings F2, F3, of definition 1.5.5 are of class Cr+4

for t, ϕ, h ∈ R, H ∈ BRd (̺) and |ε| ≤ ε2 and

may be represented in the form

F2(t, ϕ, h, H, ε) = Ω0 + 1

ν J Φ,1

(ϕ) ∂(Q,P )

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ,1

(ϕ)

+ 1

ν J Φ,1

(ϕ) ∂(Q,P )∂H

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε)(H, Φ,1

(ϕ))

+ 1

2 P(h) 1

ν J Φ,1

(ϕ) ∂2

(Q,P )

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ,1

(ϕ)[2]

+ ˜f,,2

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε) H[2]

+ P(h) ˜f,,1

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε) H + P(h)

2 ˜f,,0

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε) (1.115)

F3(t, ϕ, h, H, ε) = P(h)

d

dh P(h)

1

∂2

pH(0,0) H,1

(ϕ) ∂(Q,P )

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ,1

(ϕ)

+ P(h)

d

dh P(h)

1

∂2

p H(0,0) H,1

(ϕ) ∂(Q,P )∂H

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε)(H, Φ,1

(ϕ))

+ 1

2

P(h)2

d

dh P(h)

1

∂2

pH(0,0) H,1

(ϕ) ∂2

(Q,P )

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ,1

(ϕ)[2]

+ P(h)

d

dh P(h)

˜g,,2

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε) H[2]

+ P(h)2

d

dh P(h)

˜g,,1

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε) H + P(h)3

d

dh P(h)

˜g,,0

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε) (1.116)

where ˜f,,j

, ˜g,,j

are Cr+4

, 2π–periodic with respect to t and ϕ and

ν =

∂2

pH(0, 0)

∂2

q H(0, 0)

Φ,1

(ϕ) =

ν sin(ϕ)

cos(ϕ)

H,1

(ϕ) =

Ω0 sin(ϕ)

∂2

pH(0, 0) cos(ϕ)

. (1.117)

Moreover ˆG(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) is of class Cr+4

as well, admitting a very similar representation:

ˆG(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) = P(h) ∂(Q,P )

ˆG(0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ,1

(ϕ) + ∂H

ˆG(0, 0, 0, t, ε) H

+ ˜h,,2

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε) H[2]

+ P(h) ˜h,,1

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε) H + P(h)

2 ˜h,,0

(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε). (1.118)

PROOF: We begin this proof by recalling that due to GA 1.1b and lemma 1.5.2 the maps Ω and Φ are

of class Cω

on J , R2

respectively. However we recall that the vector fields ˆF and ˆG are of class Cr+7

only. In the following steps we will loose some of this differentiability as we perform expansions in order

to yield the expressions (1.115)–(1.118).

1. Using (1.101) together with GA 1.1c, the Taylor formula yields

Ω(p0) = Ω0 + p0

2

1

0

∂2

p0

Ω(σ p0) (1 − σ) dσ

hence setting A0(p0) :=

1

0

∂2

p0

Ω(σ p0) (1 − σ) dσ we have

ω(h) = Ω0 + P(h)

2

A0(P(h)). (1.119)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-57-320.jpg)

![44 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

2. As (Q, P) = (0, 0) is a fixed point of the Hamiltonian system (cf. GA 1.1a) we have (˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, 0) =

(0, 0), thus

(˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0) = p0 (∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(ϕ, 0) + 1

2 p0

2

(∂2

p0

˜q, ∂2

p0

˜p)(ϕ, 0)

+ 1

2 p0

3

1

0

(∂3

p0

˜q, ∂3

p0

˜p)(ϕ, σ p0) (1 − σ)2

dσ.

(1.120)

Recall that (˜q, ˜p) is 2π–periodic with respect to ϕ.

In order to find an alternative form for (∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(ϕ, 0) we take derivatives with respect to ϕ in

(1.120) obtaining

∂ϕ (˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0) = p0 ∂ϕ(∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(ϕ, 0) + 1

2 p0

2

∂ϕ(∂2

p0

˜q, ∂2

p0

˜p)(ϕ, 0) + O(p3

0). (1.121)

On the other hand, the definition of (˜q, ˜p) implies

∂ϕ (˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0) = 1

Ω(p0) ∂t(q, p)( ϕ

Ω(p0) ; 0, p0) = 1

Ω(p0) J∇H ((˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0))

= 1

Ω(p0) JD2

H(0, 0) ((˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0)) + 1

2 JD3

H(0, 0) ((˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0))

[2]

+ 1

2

1

0

JD4

H (σ (˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0)) (1 − σ)2

dσ ((˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0))

[3]

.

(1.122)

Plugging (1.120) into (1.122) and comparing coefficients of equal powers of p0 in (1.121) one obtains

∂ϕ(∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(ϕ, 0) = 1

Ω0

JD2

H(0, 0)(∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(ϕ, 0)

∂ϕ(∂2

p0

˜q, ∂2

p0

˜p)(ϕ, 0) = 1

Ω0

JD2

H(0, 0)(∂2

p0

˜q, ∂2

p0

˜p)(ϕ, 0)

+JD3

H(0, 0) ((∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(ϕ, 0))

[2]

.

Differentiating the initial condition (˜q, ˜p) (0, p0) = (0, p0) with respect to p0 and evaluating these

derivatives for p0 = 0 yields the following initial conditions :

(∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(0, 0) = (0, 1)

(∂2

p0

˜q, ∂2

p0

˜p)(0, 0) = (0, 0).

Taking into account D3

H(0, 0) = 0 we eventually find

(∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(ϕ, 0) = e

ϕ

Ω0

JD2

H(0,0) 0

1

(∂2

p0

˜q, ∂2

p0

˜p)(ϕ, 0) = 0.

The formula for etJD2

H(0,0)

found in (1.104), i.e.

etJD2

H(0,0)

=

cos(Ω0 t)

∂2

pH(0,0)

∂2

q H(0,0) sin(Ω0 t)

−

∂2

q H(0,0)

∂2

p H(0,0) sin(Ω0 t) cos(Ω0 t)

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-58-320.jpg)

![1.5. The Action Angle Coordinates 45

implies

(∂p0 ˜q, ∂p0 ˜p)(ϕ, 0) =

∂2

p H(0,0)

∂2

q H(0,0) sin(ϕ)

cos(ϕ)

.

Thus setting ν :=

∂2

p H(0,0)

∂2

q H(0,0) and Φ,1

(ϕ) :=

ν sin(ϕ)

cos(ϕ)

together with

A1(ϕ, p0) := 1

2

1

0

(∂3

p0

˜q, ∂3

p0

˜p)(ϕ, σ p0) (1 − σ)2

dσ

we conclude from (1.120)

Φ(ϕ, h) = (˜q, ˜p)(ϕ, P(h)) = P(h) Φ,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

3

A1(ϕ, P(h)). (1.123)

3. The identities ∇H(0, 0) = 0 and D3

H(0, 0) = 0 imply together with (1.123)

∇H(Φ(ϕ, h)) = D2

H(0, 0) Φ(ϕ, h) + 1

2

1

0

D4

H (σ Φ(ϕ, h)) (1 − σ)2

dσ (Φ(ϕ, h))

[3]

= P(h) D2

H(0, 0) Φ,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

3

D2

H(0, 0) A1(ϕ, P(h))

+P(h)

3 1

2

1

0

D4

H (σ Φ(ϕ, h)) (1 − σ)2

dσ Φ,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

2

A1(ϕ, P(h))

[3]

such that when setting H,1

(ϕ) :=

Ω0 sin(ϕ)

∂2

pH(0, 0) cos(ϕ)

,

A2(ϕ, p0) := D2

H(0, 0) A1(ϕ, p0) + 1

2

1

0

D4

H (σ (˜q, ˜p) (ϕ, p0)) (1 − σ)2

dσ Φ,1

(ϕ) + p0

2

A1(ϕ, p0)

[3]

we obtain

∇H(Φ(ϕ, h)) = P(h)

∂2

q H(0, 0) 0

0 ∂2

pH(0, 0)

ν sin(ϕ)

cos(ϕ)

+ P(h)

3

A2(ϕ, P(h))

= P(h) H,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

3

A2(ϕ, P(h)). (1.124)

The map A2 is 2π–periodic with respect to ϕ.

4. In a similar way we may write

∂pH(0, P(h)) = P(h) ∂2

pH(0, 0) + 1

2 P(h)3

1

0

∂4

pH(0, σ P(h)) (1 − σ)2

dσ

= P(h)

∂2

pH(0, 0) + 1

2 P(h)

2

1

0

∂4

pH(0, σ P(h)) (1 − σ)2

dσ

= P(h) A3(P(h)),](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-59-320.jpg)

![46 Chapter 1. Reduction to a Planar System

where A3(p0) := ∂2

pH(0, 0) + 1

2 p0

2

1

0

∂4

pH(0, σ p0) (1 − σ)2

dσ satisfies A3(0) = ∂2

pH(0, 0).

Hence we conclude

d

dh H(0, P(h)) = ∂pH(0, P(h)) d

dh P(h) = d

dh P(h) P(h) A3(P(h)). (1.125)

5. Since by assumption A3(P(h)) =

∂pH(0,P(h))

P(h) = 0 the map h → 1

A3(P(h)) is of class Cω

. This

together with 1.97 a implies that the function P(h)

d

dh P(h) A3(P(h))

is of class Cω

for h ∈ R.

6. As ˆF(0, 0, H, t, ε) = 0 (cf. (1.96), (1.88) respectively), we find ∂k

H

ˆF(0, 0, H, t, ε) = 0 for all 0 ≤ k ≤

r + 7, hence the Taylor expansion of ˆF(Q, P, H, t, ε) is of the form

ˆF(Q, P, H, t, ε) = ∂(Q,P )

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) (Q, P)

+∂(Q,P )∂H

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε)(H, (Q, P)) + 1

2 ∂2

(Q,P )

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) (Q, P)

[2]

+A4,1((Q, P) , H, t, ε)(H[2]

, (Q, P)) + A4,2((Q, P) , H, t, ε)(H, (Q, P)

[2]

)

+A4,3((Q, P) , H, t, ε) (Q, P)

[3]

where the maps A4,1, A4,2 and A4,3 are of class Cr+4

and 2π–periodic with respect to ϕ. Hence

we rewrite ˆF(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) as follows:

ˆF(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) = ∂(Q,P )

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ(ϕ, h) (1.126)

+∂(Q,P )∂H

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε)(H, Φ(ϕ, h)) + 1

2 ∂2

(Q,P )

ˆF(0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ(ϕ, h)[2]

+A4,1(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε)(H[2]

, Φ(ϕ, h)) + A4,2(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε)(H, Φ(ϕ, h)

[2]

)

+A4,3(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) Φ(ϕ, h)[3]

.

7. With ˆG(0, 0, 0, t, ε) = 0, a similar representation is found for ˆG(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε):

ˆG(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) = ∂(Q,P )

ˆG(0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ(ϕ, h) + ∂H

ˆG(0, 0, 0, t, ε) H (1.127)

+A5,0(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) H[2]

+ A5,1(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε)(H, Φ(ϕ, h))

+A5,2(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) Φ(ϕ, h)

[2]

where the maps A5,2, A5,1 and A5,0 are 2π–periodic with respect to ϕ.

8. Summarizing the representations (1.119), (1.123), (1.125) and (1.126) we rewrite the term presented

in (1.110) as follows

ω(h)

d

dh

H(0,P(h))

J ∂hΦ(ϕ, h) ˆF (Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) =

Ω0 + P(h)2 A0(P(h))

d

dh

P(h) P(h) A3(P(h))

J d

dh

P(h) Φ

,1

(ϕ) + 3 d

dh

P(h) P(h)

2

A1(ϕ, P(h)) + d

dh

P(h) P(h)

3

∂p0 A1(ϕ, P(h)) · · ·

· · · P(h) ∂(Q,P )

ˆF (0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ

,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

2

A1(ϕ, P(h)) + P(h) ∂(Q,P )∂H

ˆF (0, 0, 0, t, ε) H, Φ

,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

2

A1(ϕ, P(h))

+ P(h)

2 1

2

∂

2

(Q,P )

ˆF (0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ

,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

2

A1(ϕ, P(h))

[2]

+ P(h) A4,1(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) H

[2]

, Φ

,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

2

A1(ϕ, P(h))

+ P(h)

2

A4,2(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) H, Φ

,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

2

A1(ϕ, P(h))

[2]

+ P(h)

3

A4,3(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) Φ

,1

(ϕ) + P(h)

2

A1(ϕ, P(h))

[3]

=:

Ω0

A3(0)

· · ·

· · · JΦ

,1

(ϕ) ∂(Q,P )

ˆF (0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ

,1

(ϕ) + ∂(Q,P )∂H

ˆF (0, 0, 0, t, ε) H, Φ

,1

(ϕ) + A4,1(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) H

[2]

, Φ

,1

(ϕ)

+ P(h) JΦ

,1

(ϕ) 1

2

∂

2

(Q,P )

ˆF (0, 0, 0, t, ε) Φ

,1

(ϕ)

[2]

+ A4,2(Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) H, Φ

,1

(ϕ)

[2]

+ P(h)

2

A6(ϕ, P(h), H, t, ε)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/134355b9-c3ce-41ca-8cf9-85f751f98ea6-160201091932/85/Invariant-Manifolds-Passage-through-Resonance-Stability-and-a-Computer-Assisted-Application-to-a-Synchronous-Motor-60-320.jpg)

![1.5. The Action Angle Coordinates 47

which eventually leads to the representation claimed in (1.115). As a further consequence of this

form we conclude that the map F2 is of class Cr+4

with respect to h.

9. Summarizing the representations (1.124), (1.125) and (1.126) we rewrite F3 defined in (1.110) as

follows

1

d

dh

H(0,P(h))

∇H(Φ(ϕ, h)) ˆF (Φ(ϕ, h), H, t, ε) =

1

d

dh