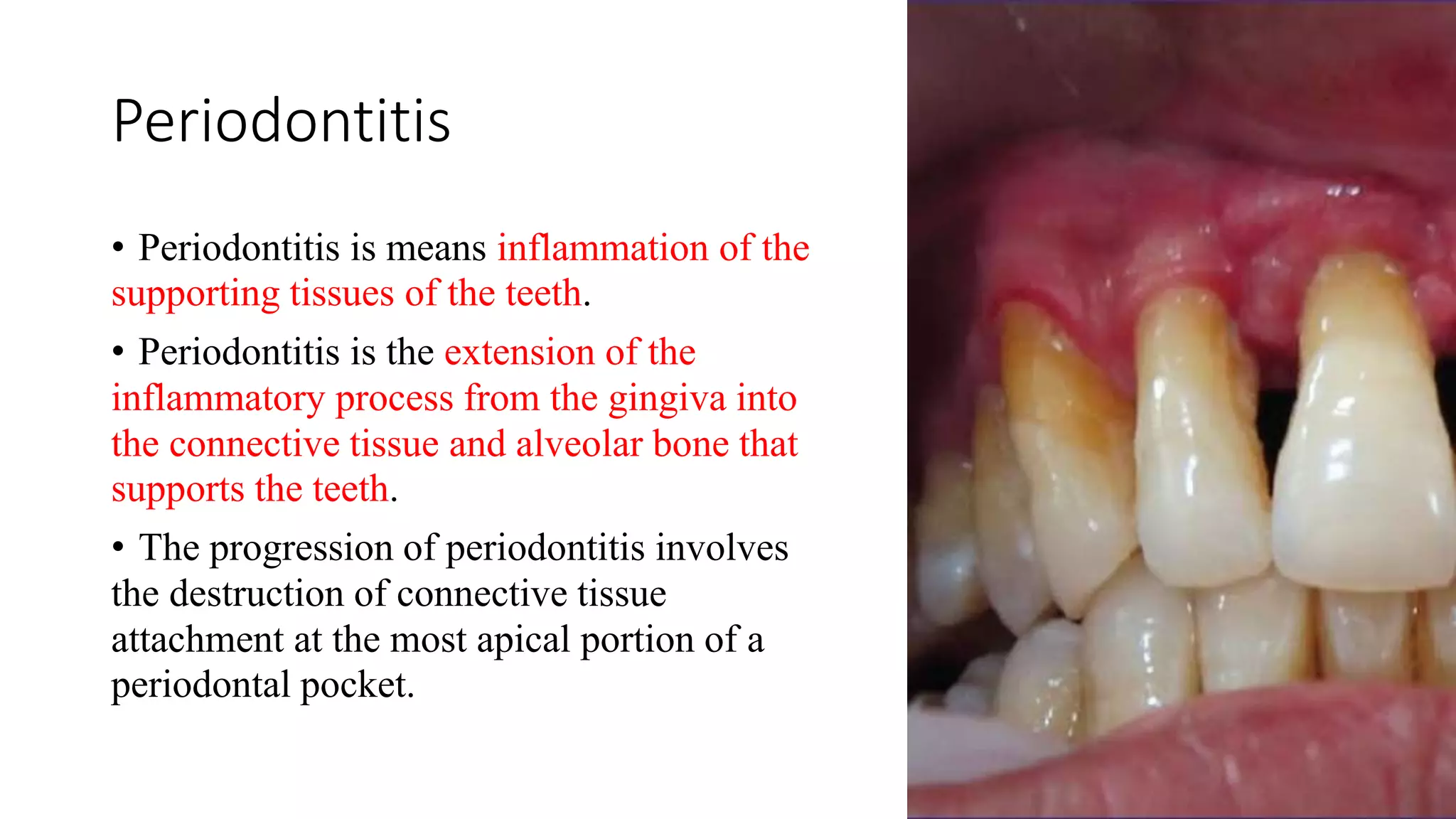

This document provides information on diagnosing periodontal disease. It discusses gingivitis as inflammation of the gums without bone loss. Periodontitis involves inflammation spreading below the gumline and destroying the bone and tissues that support the teeth. Key risk factors for periodontal disease include poor oral hygiene, smoking, and diabetes. The diagnosis involves examining the medical history, dental history, oral cavity, teeth, gums, and radiographs to determine the type and severity of periodontal disease present.