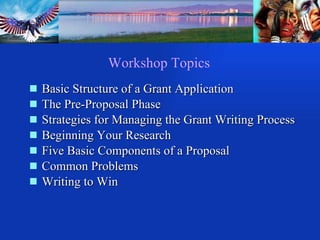

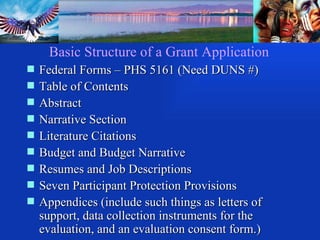

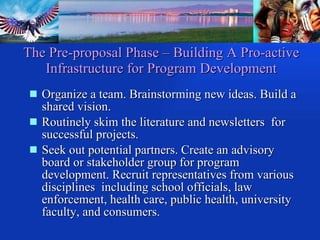

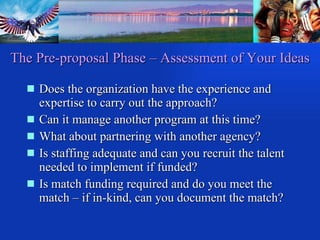

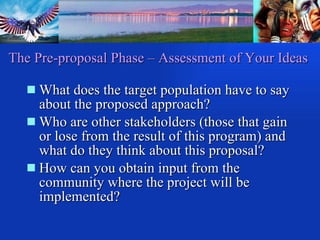

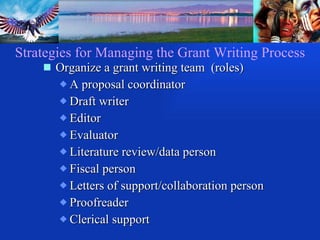

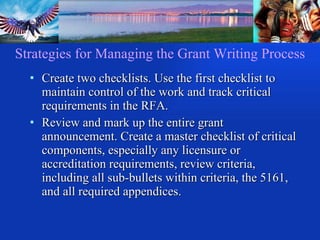

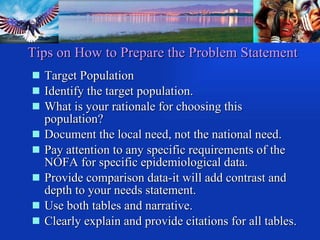

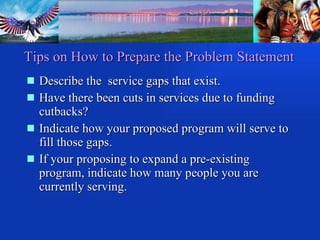

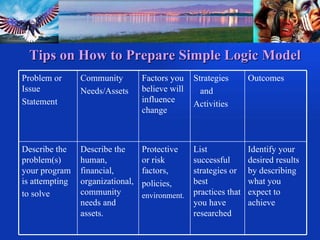

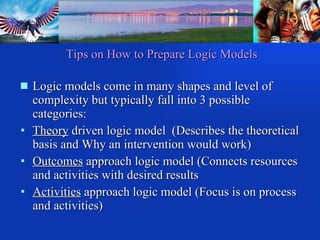

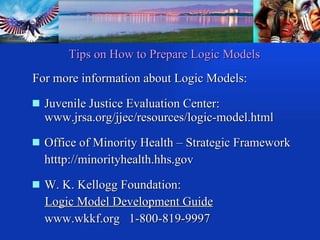

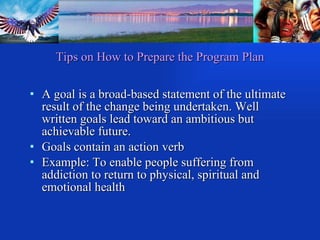

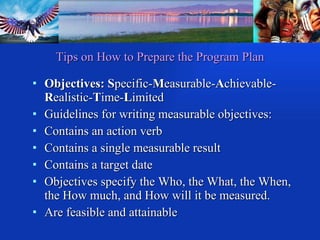

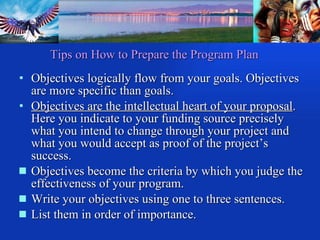

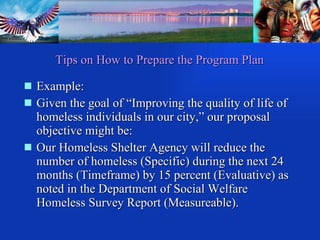

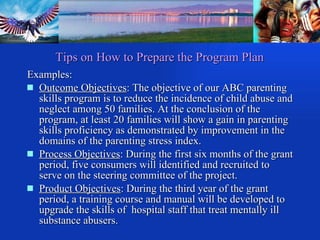

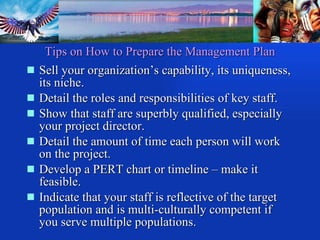

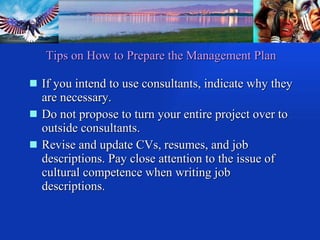

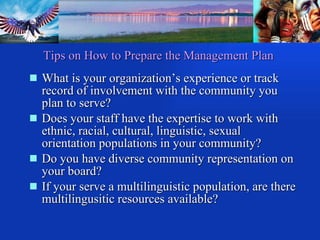

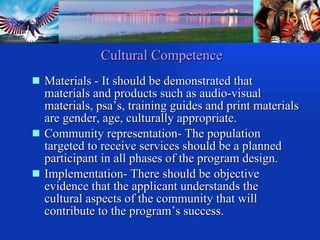

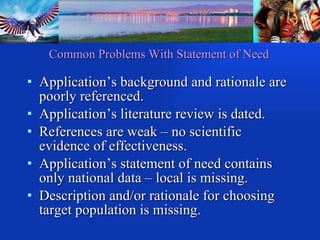

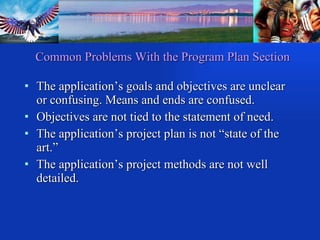

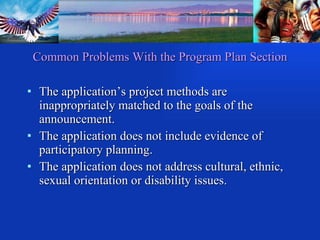

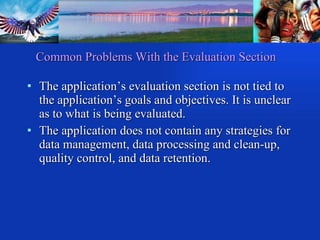

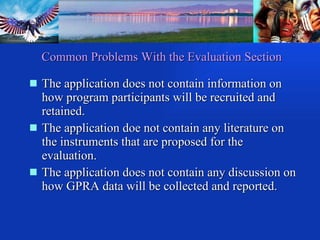

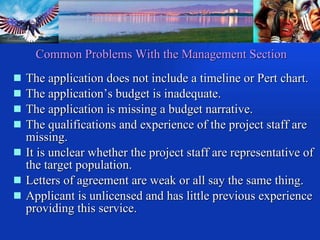

The document provides tips for developing winning program proposals, including the basic structure of a grant application, strategies for managing the grant writing process, tips for preparing key sections like the problem statement, program plan, evaluation, and management plan. It emphasizes establishing community needs, developing clear goals and measurable objectives, involving stakeholders, and demonstrating cultural competence throughout.