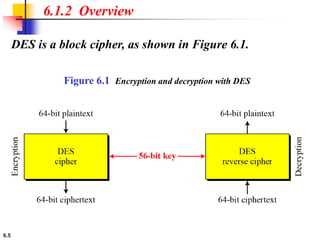

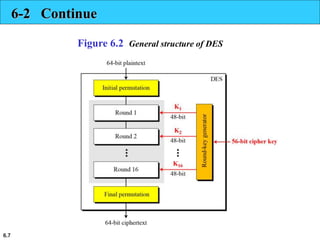

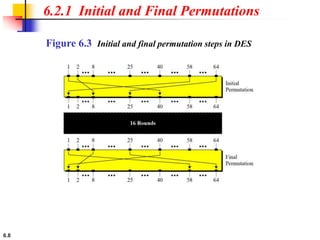

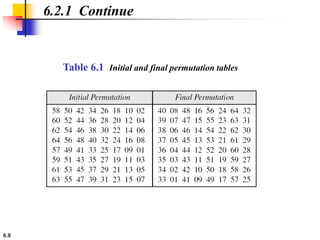

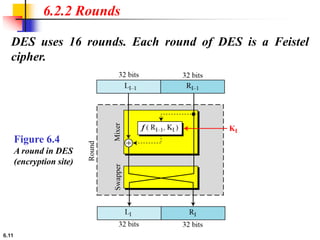

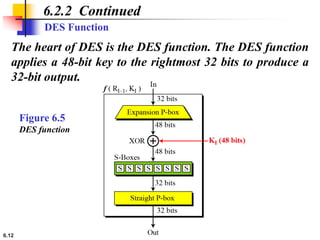

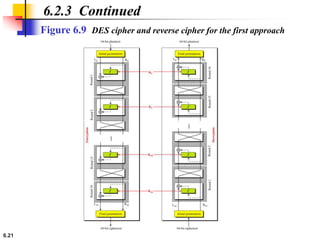

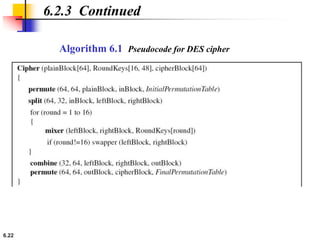

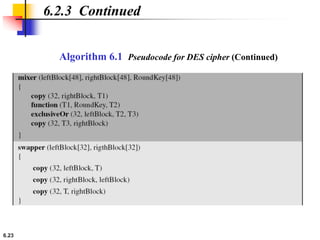

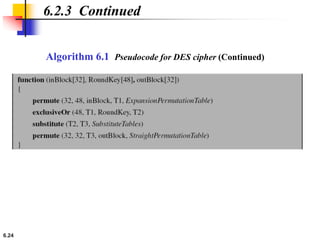

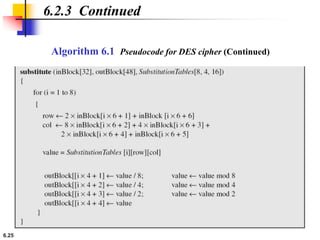

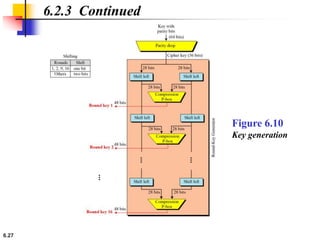

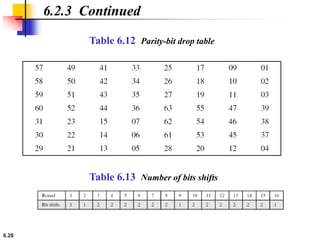

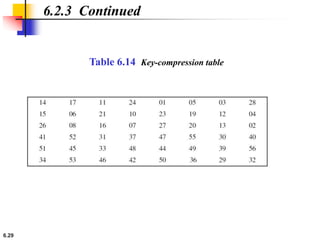

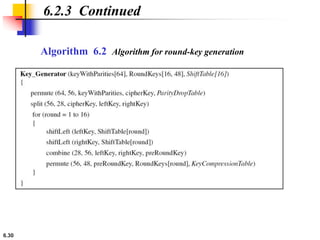

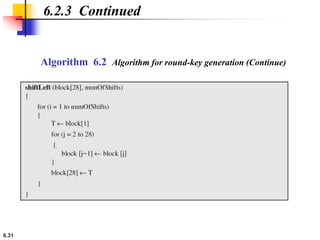

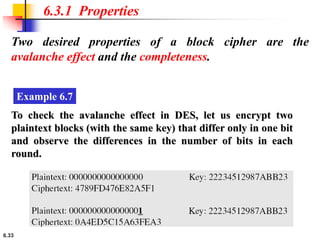

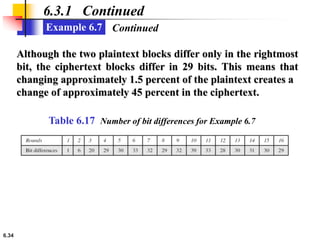

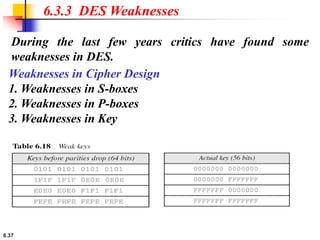

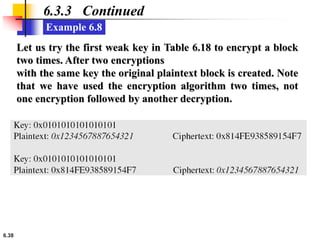

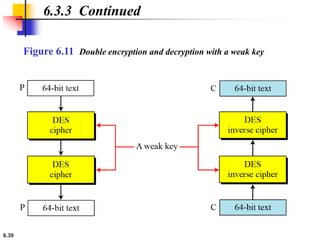

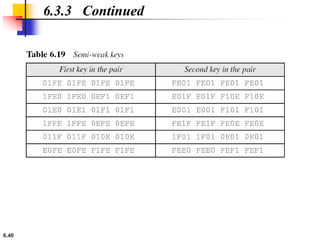

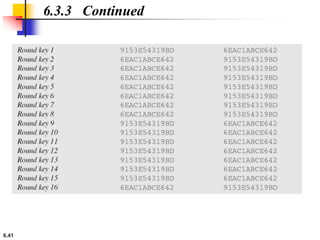

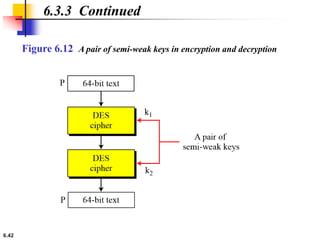

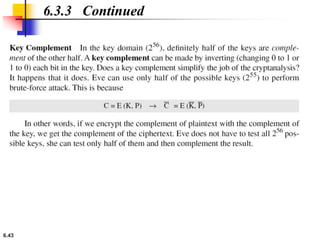

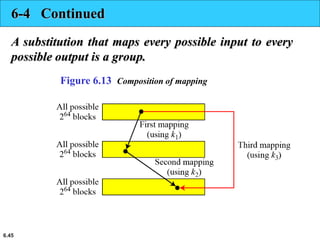

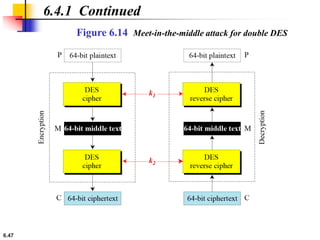

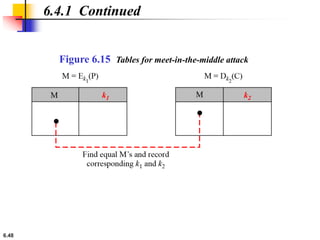

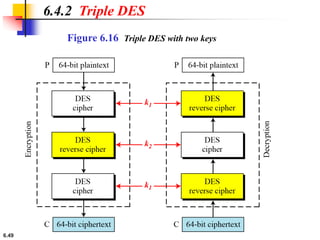

This document provides an overview of the Data Encryption Standard (DES). It discusses the history and basic structure of DES, including the initial and final permutations, 16 rounds of encryption, and key generation process. It also analyzes the properties and design criteria of DES, and describes some weaknesses such as brute force attacks breaking it with 255 encryptions. Finally, it discusses ways to strengthen DES such as double and triple DES to increase the effective key size.