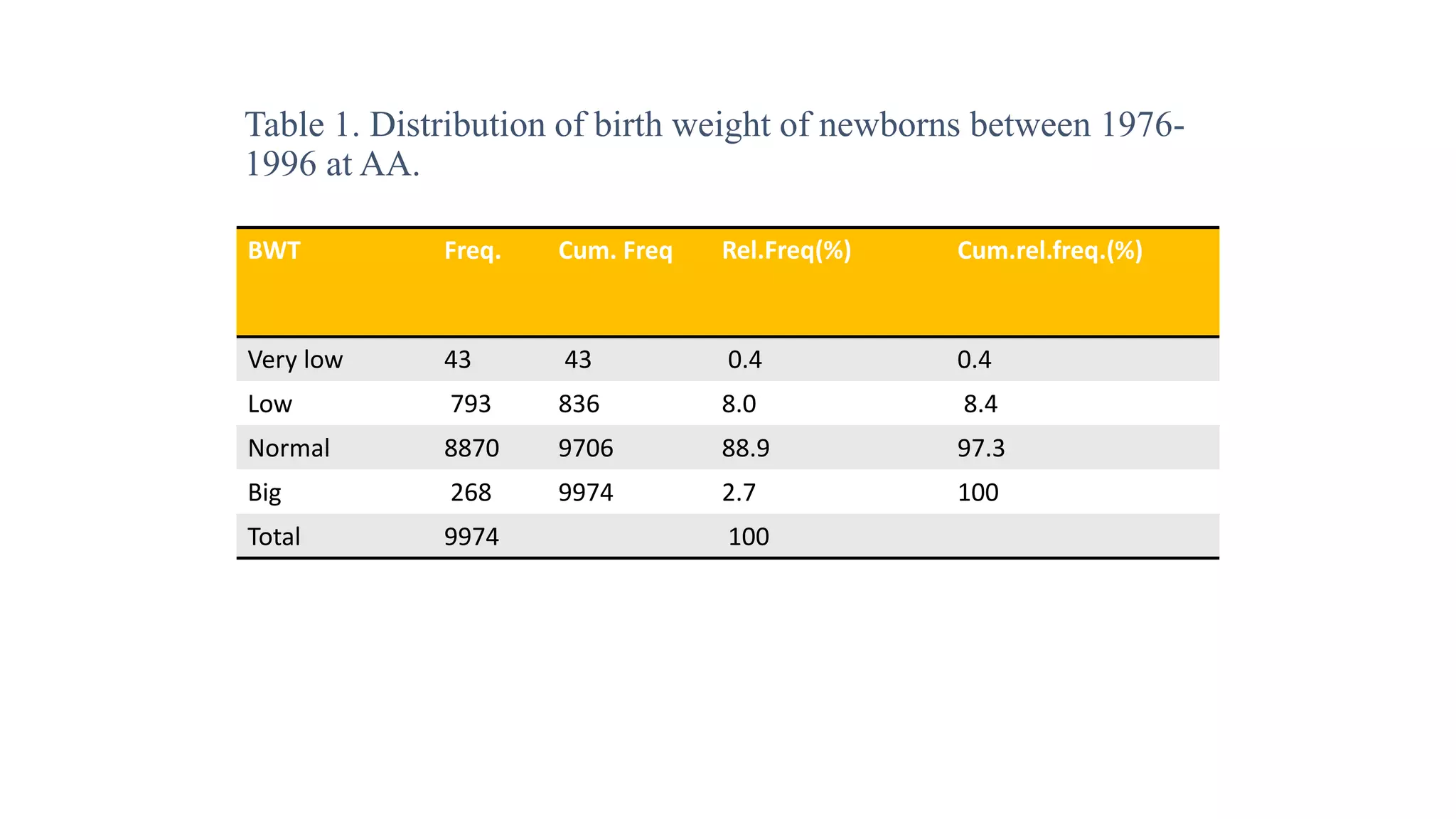

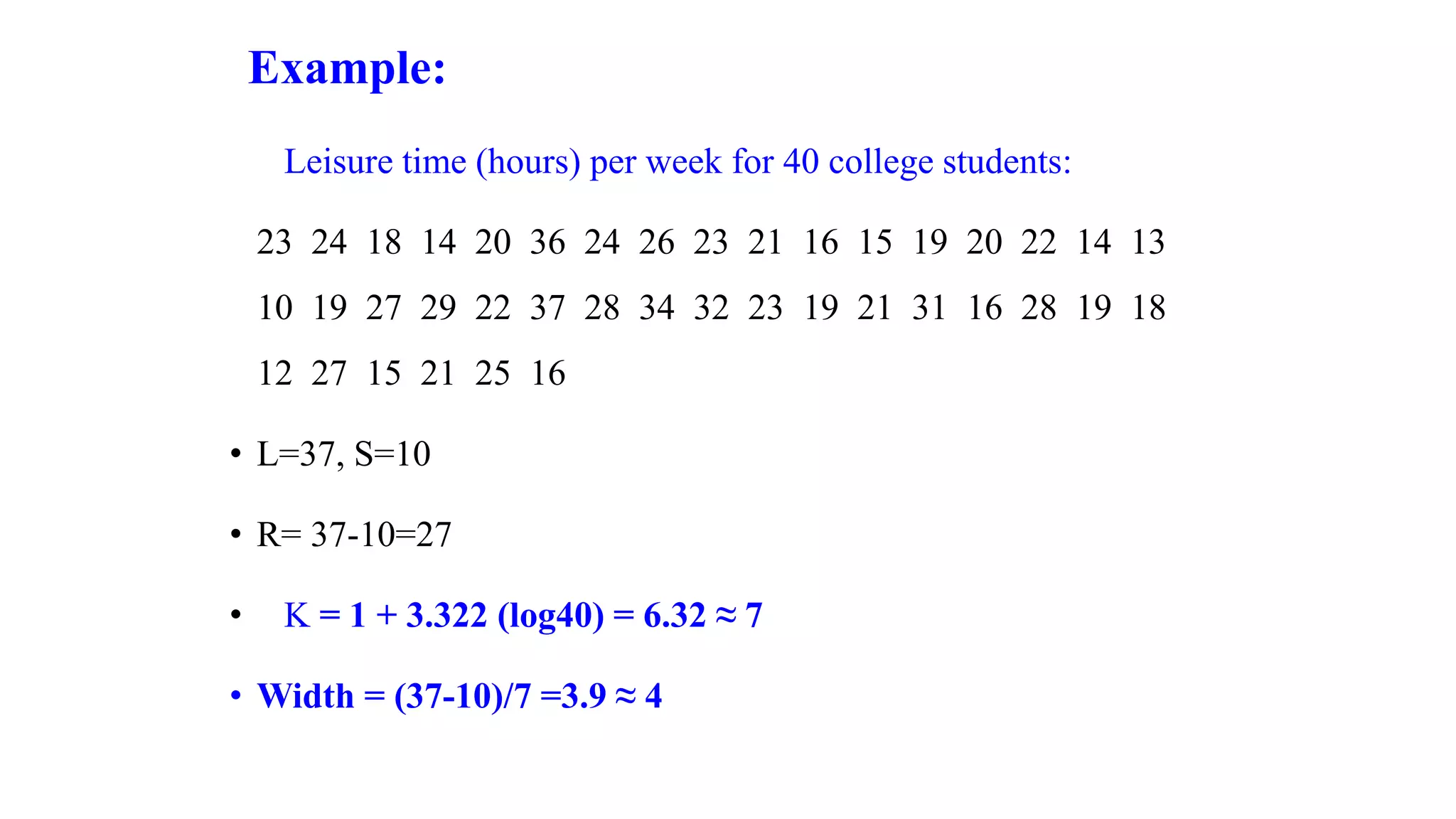

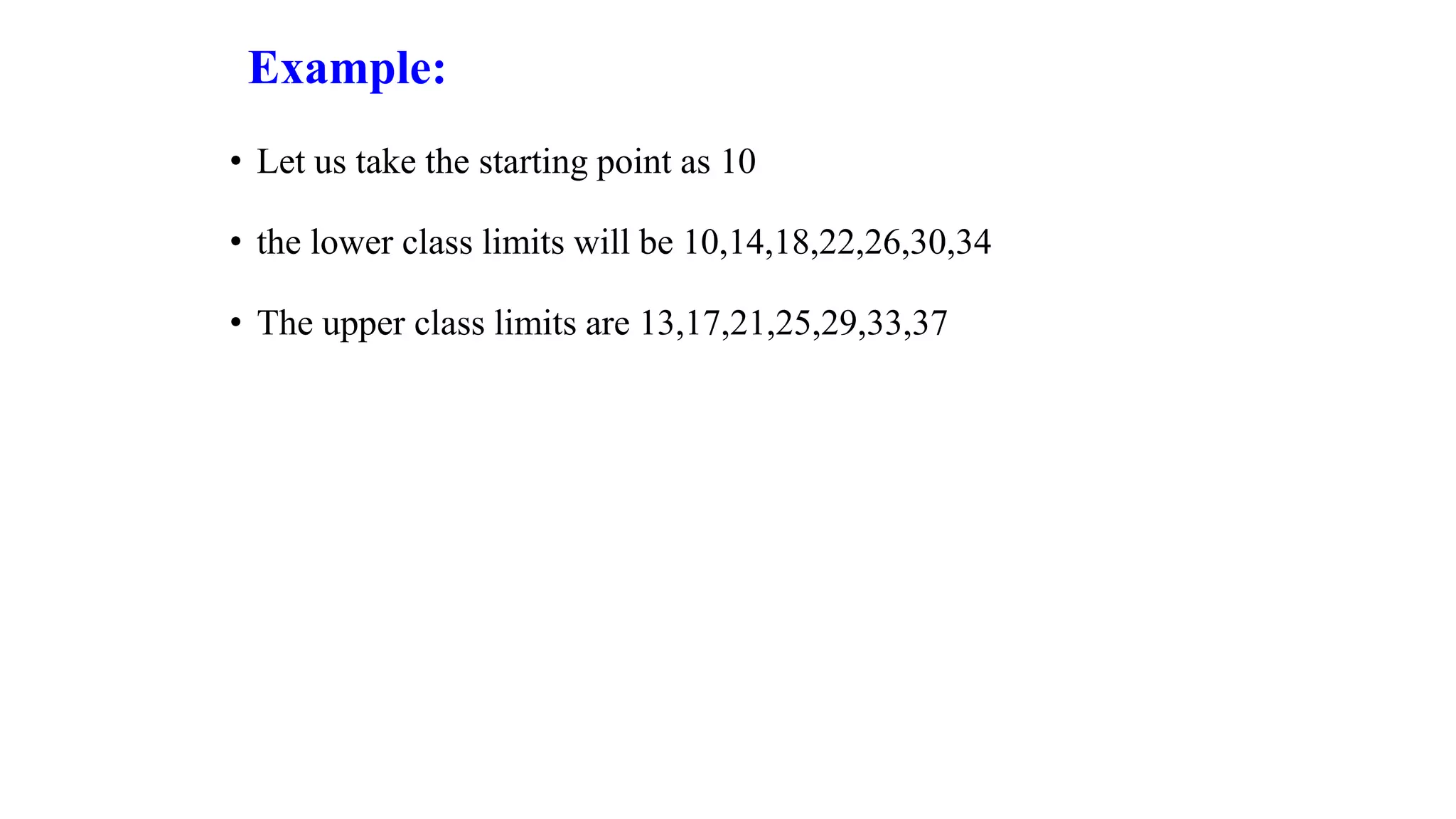

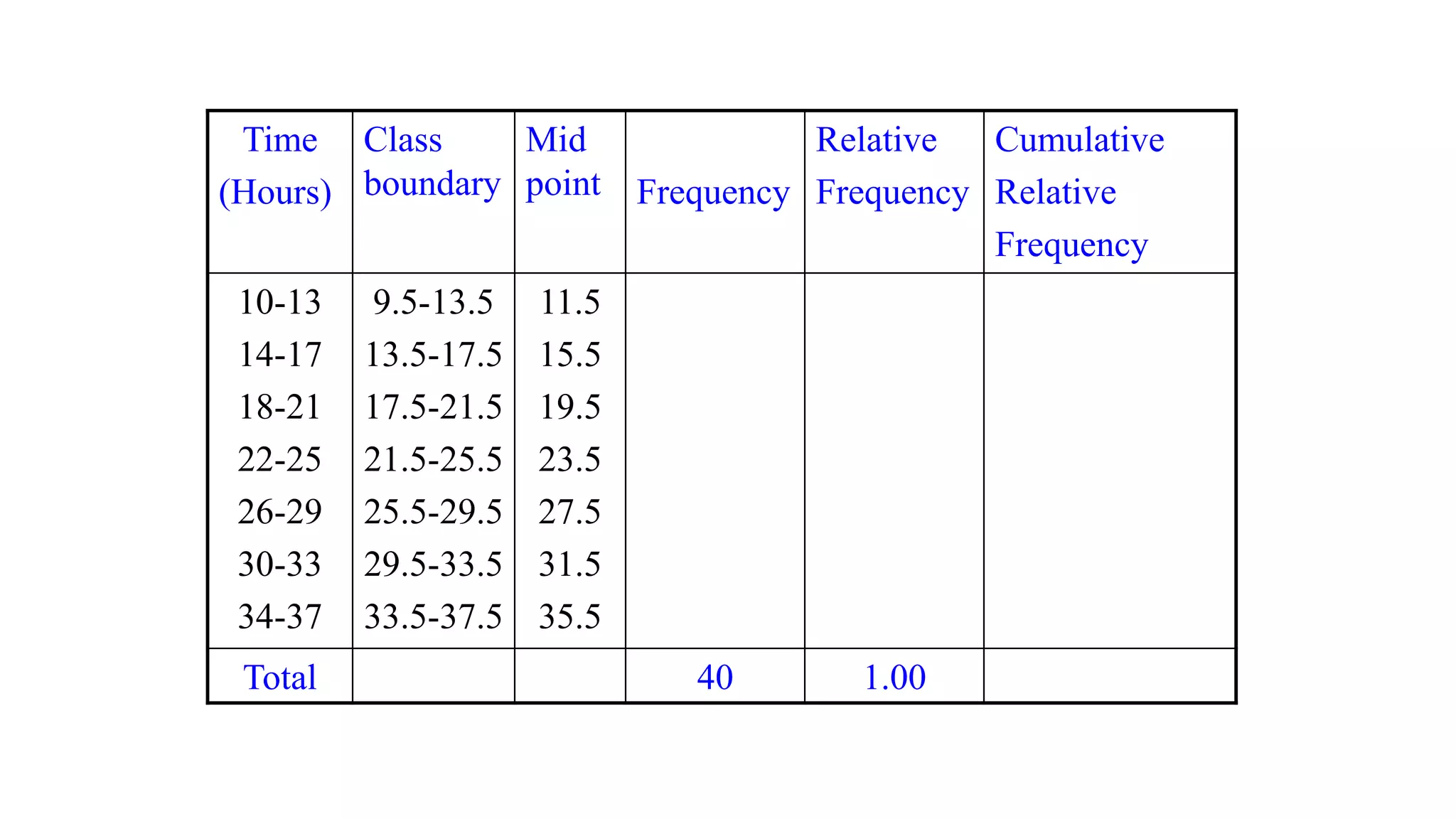

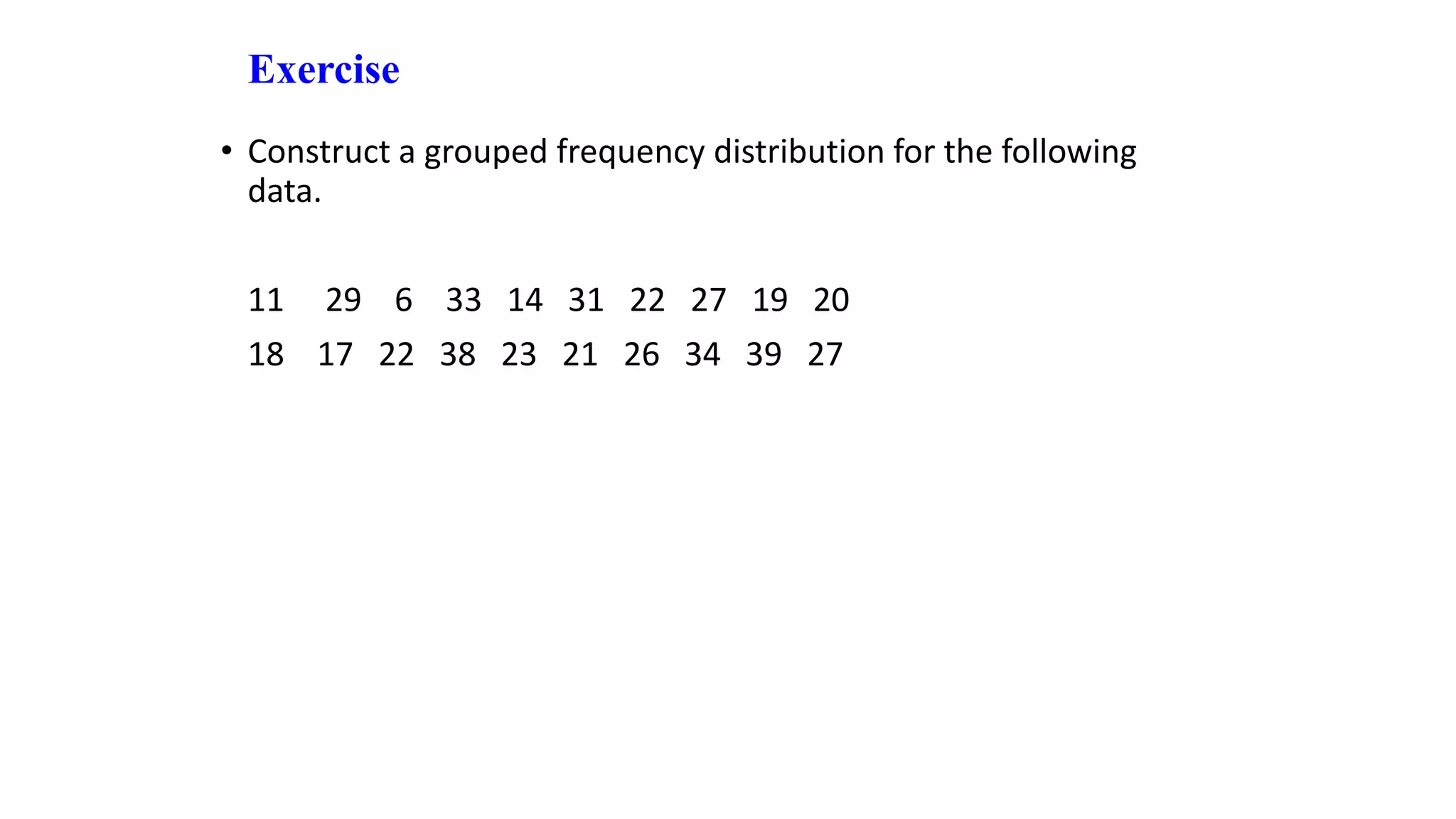

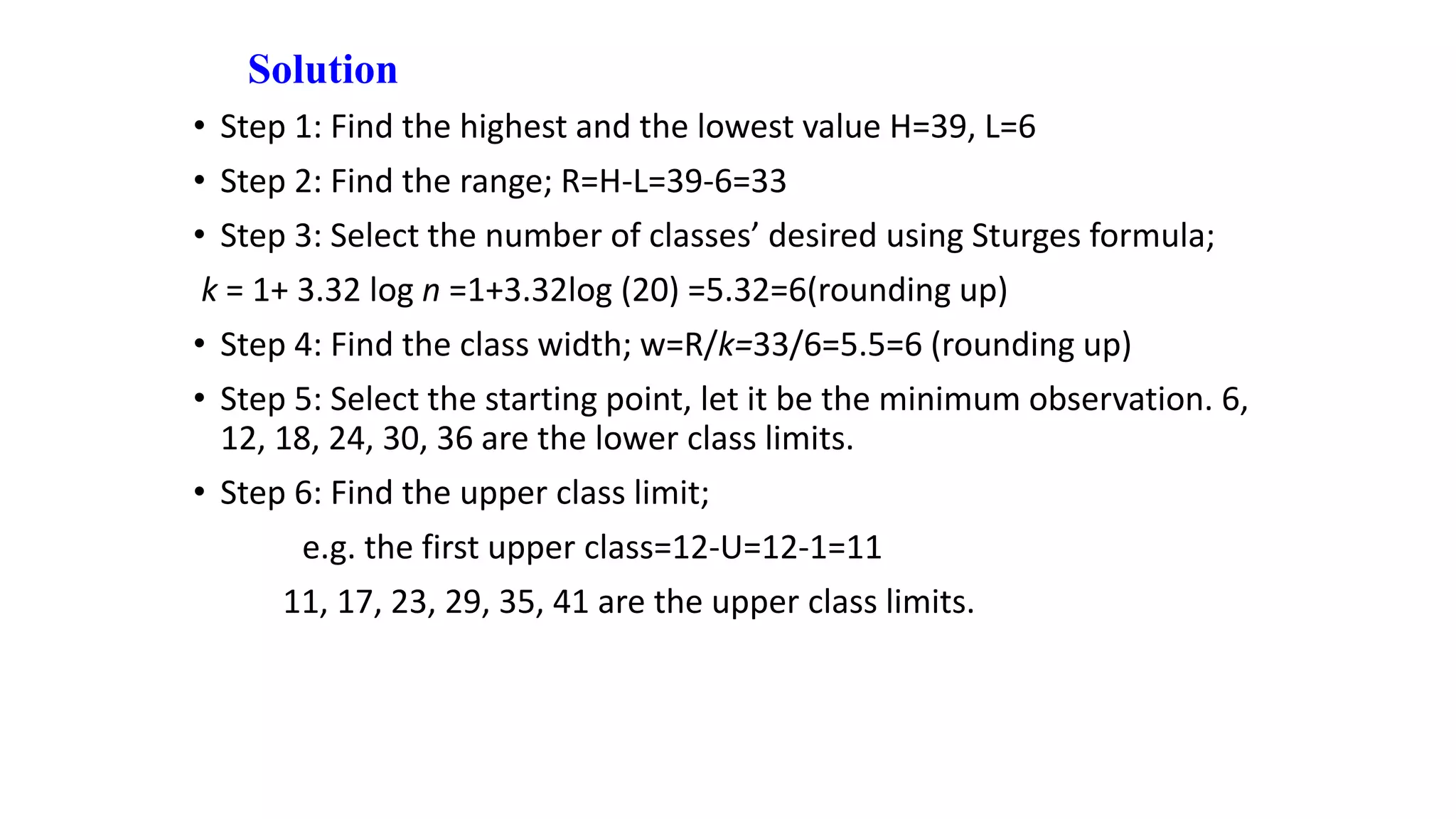

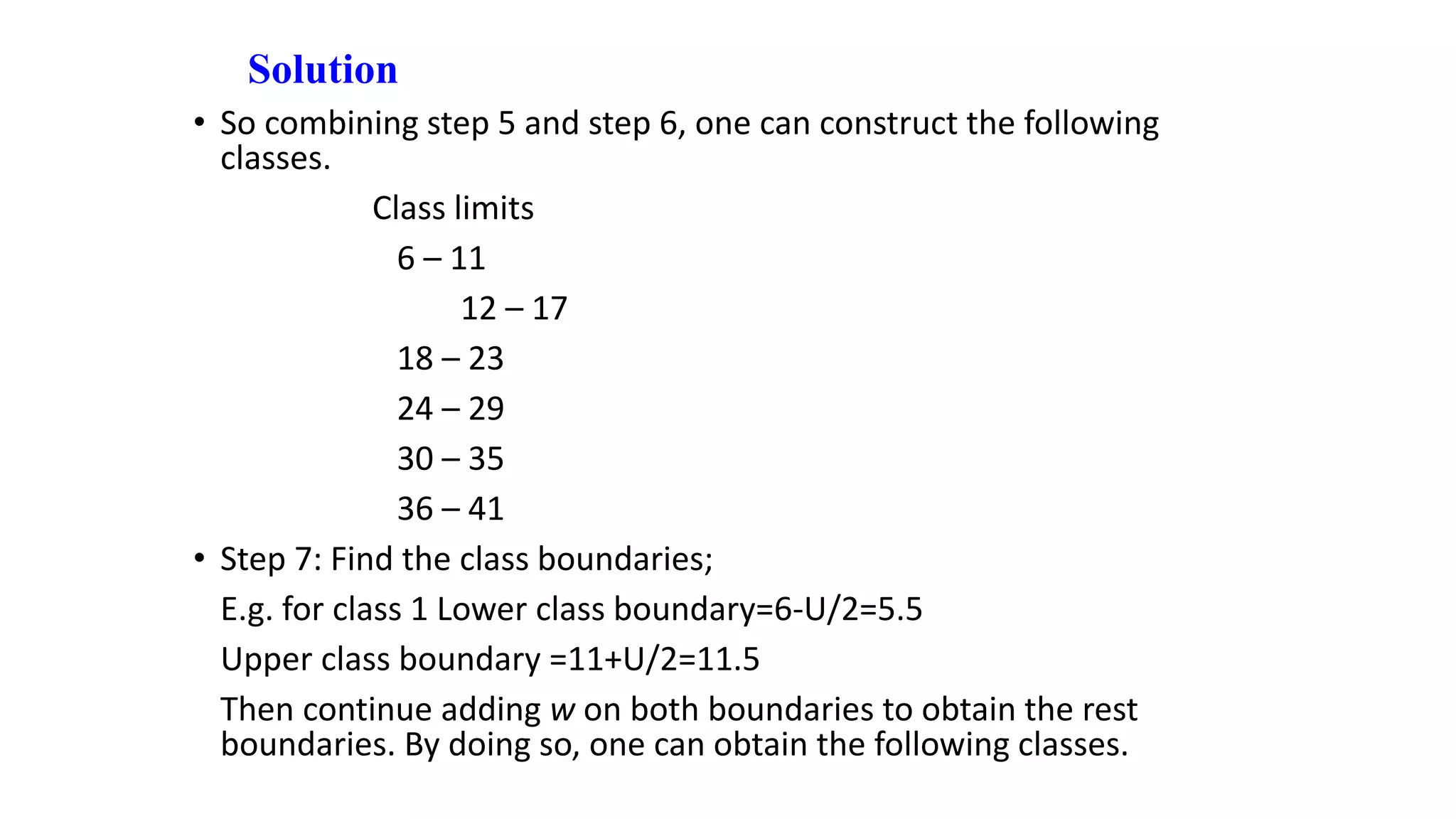

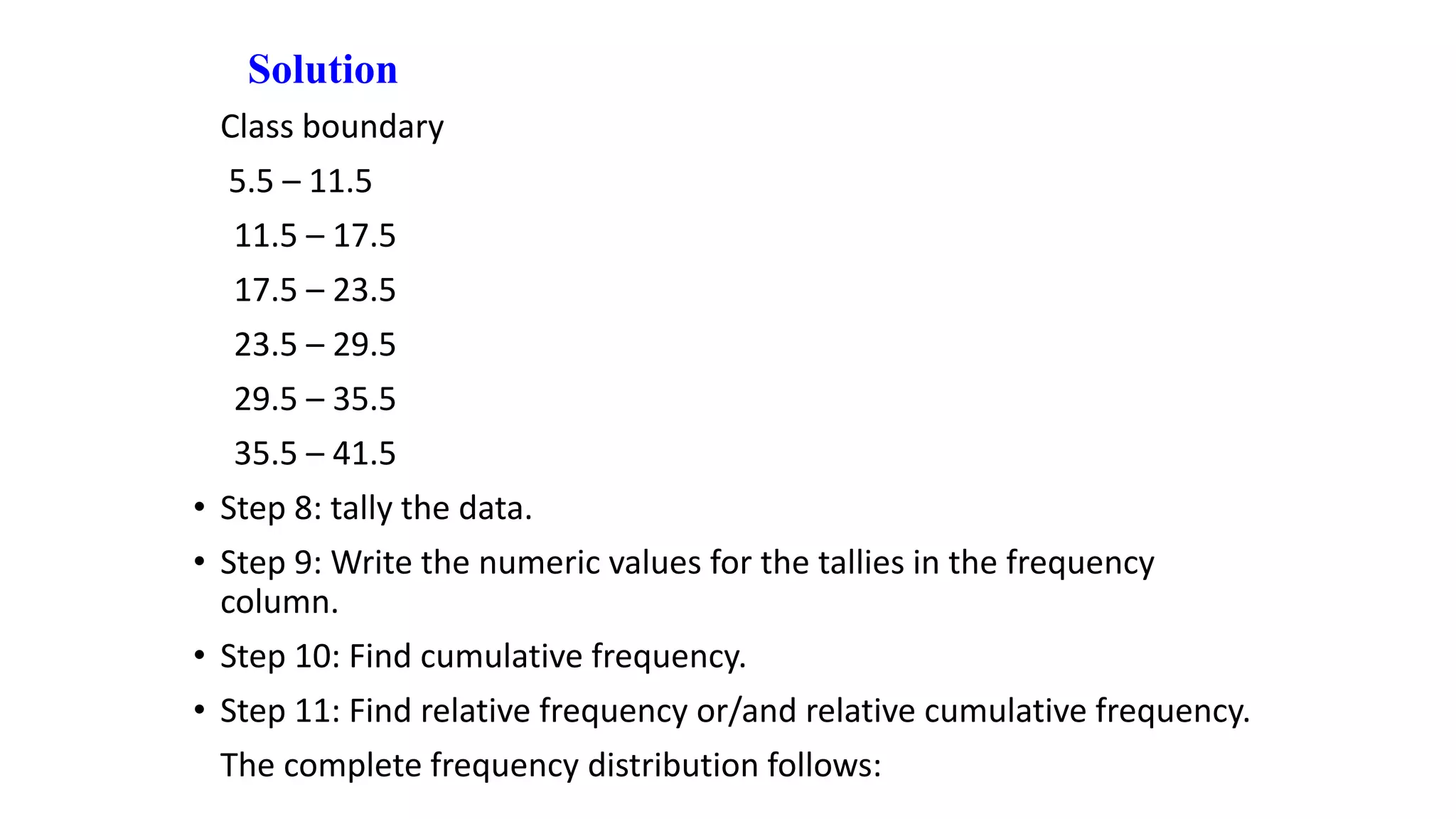

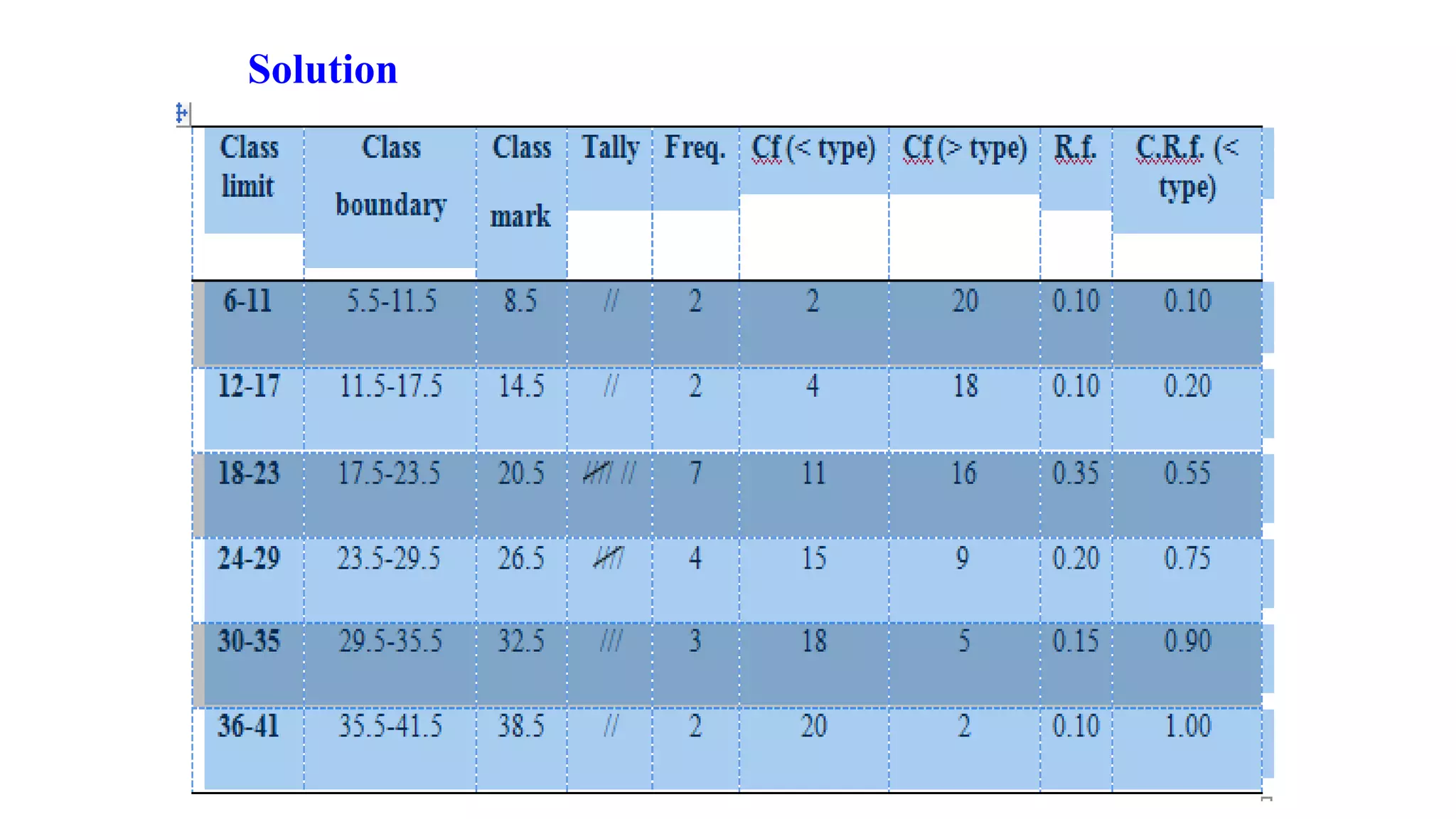

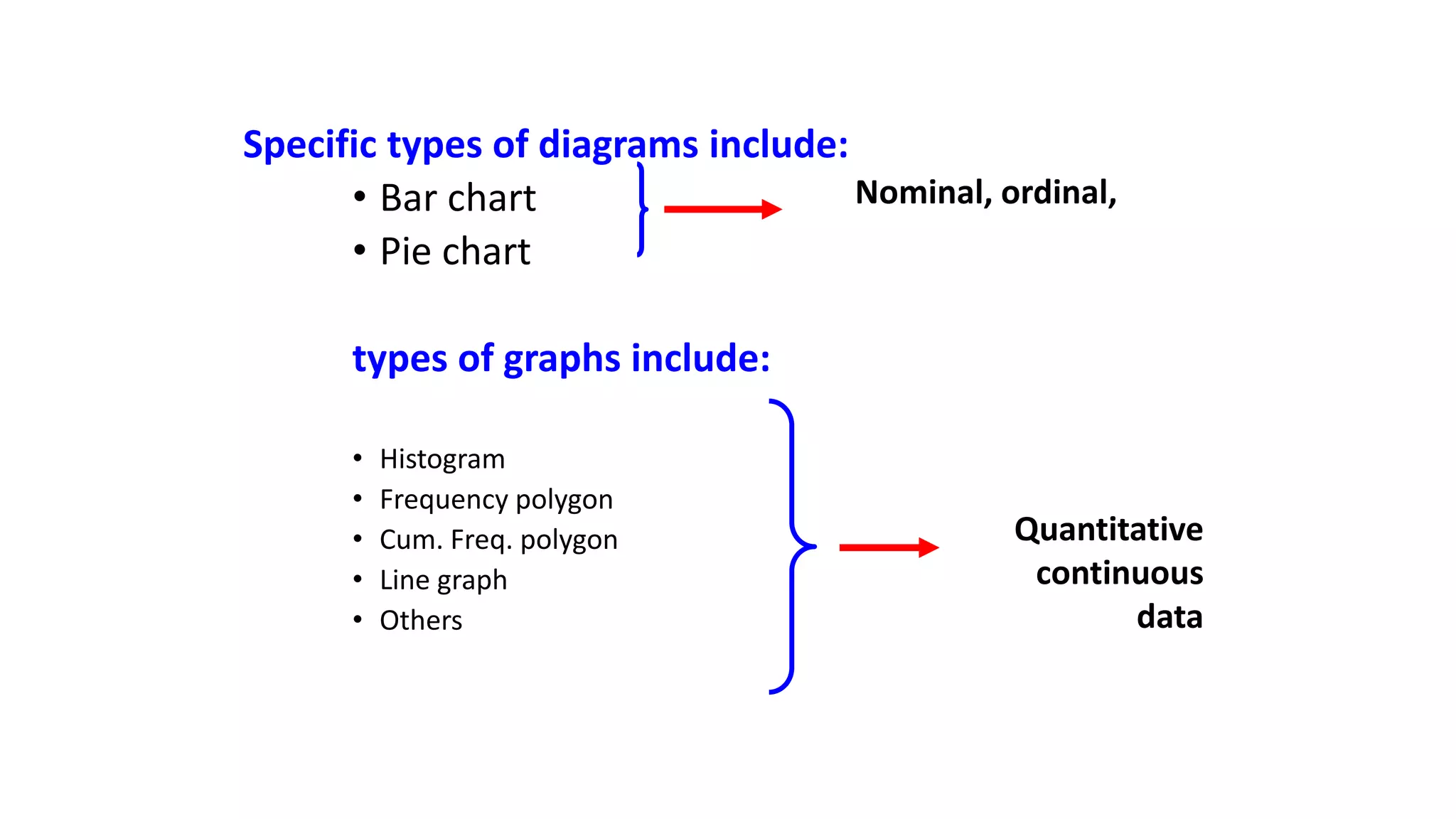

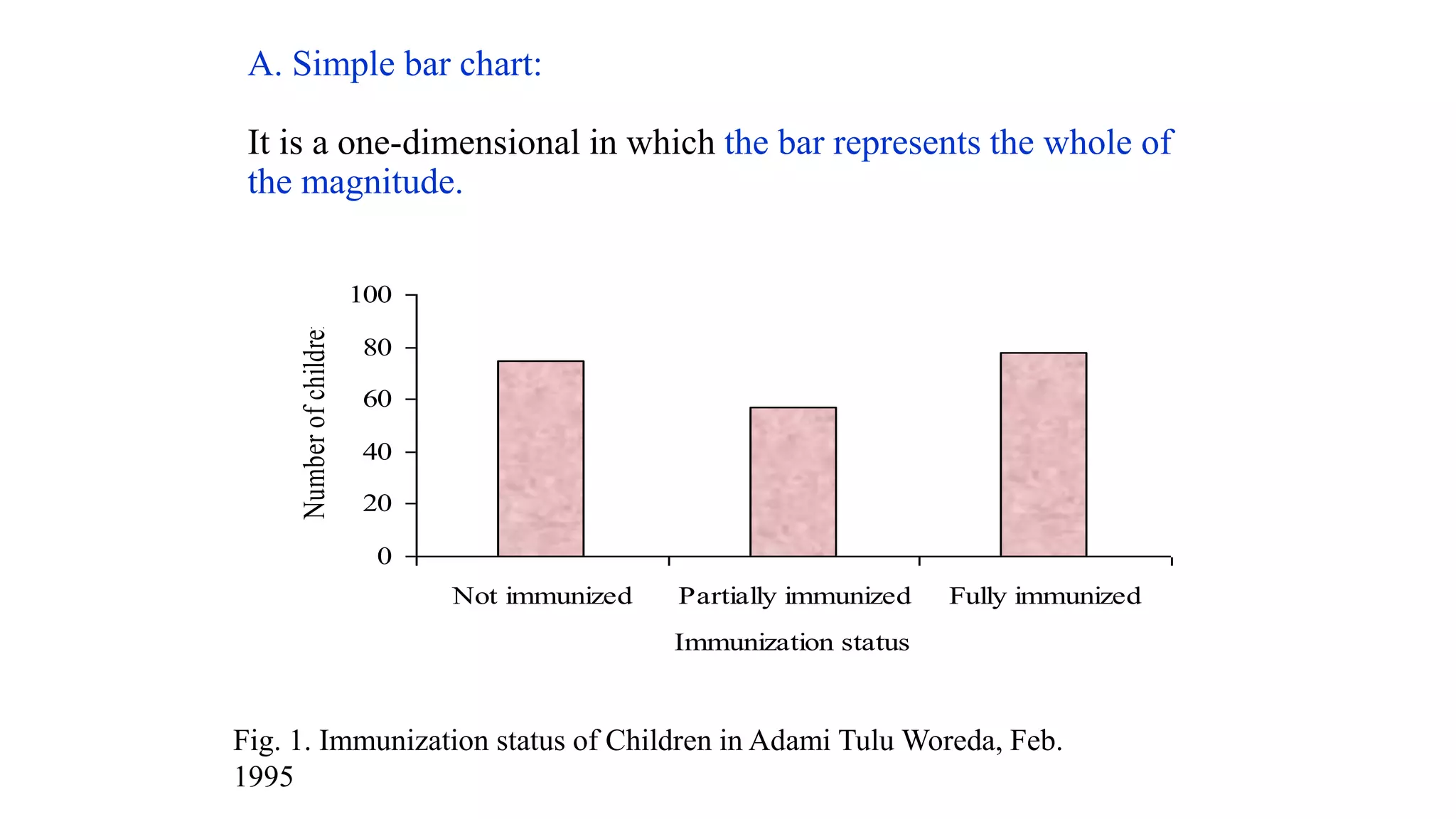

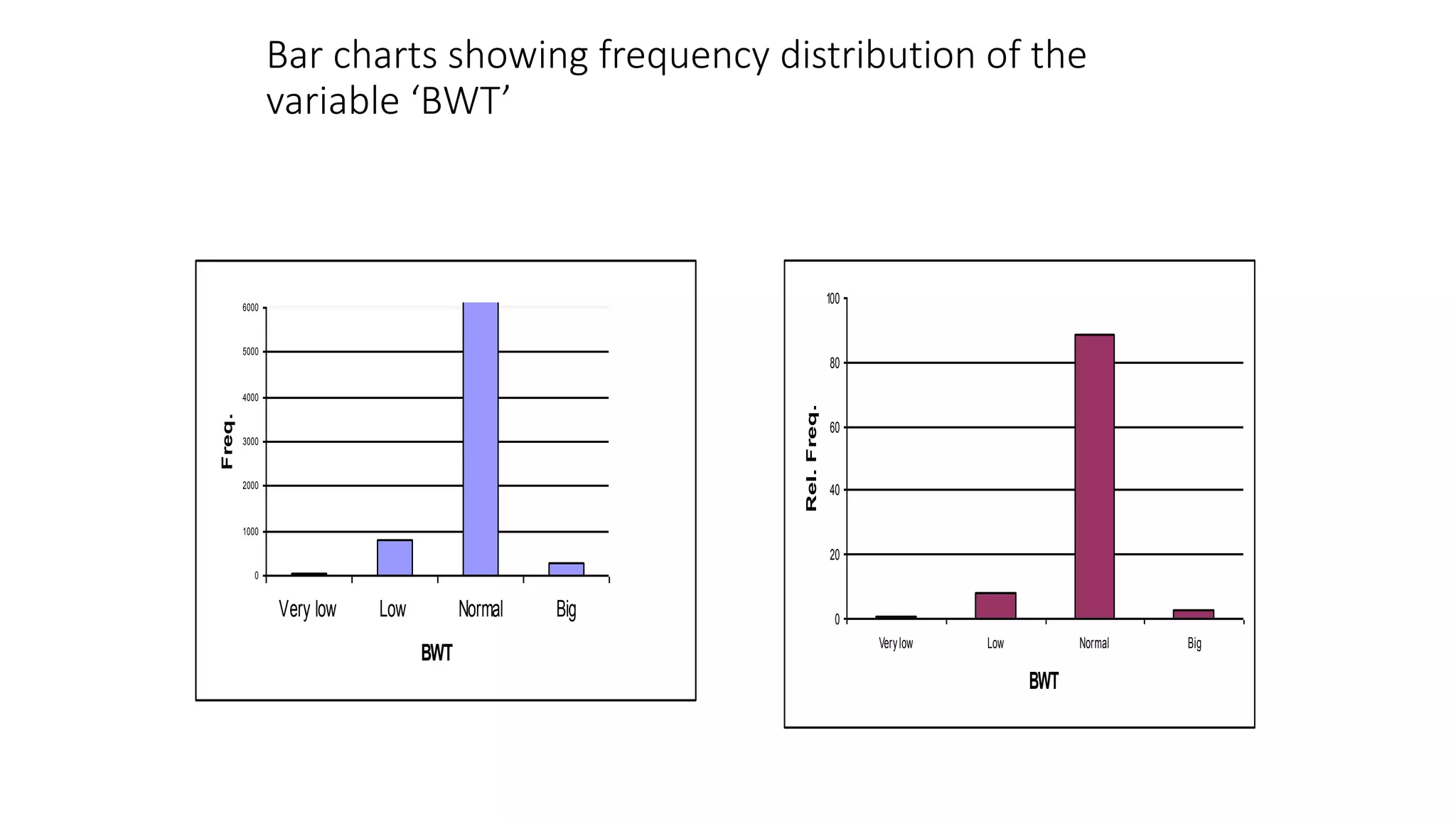

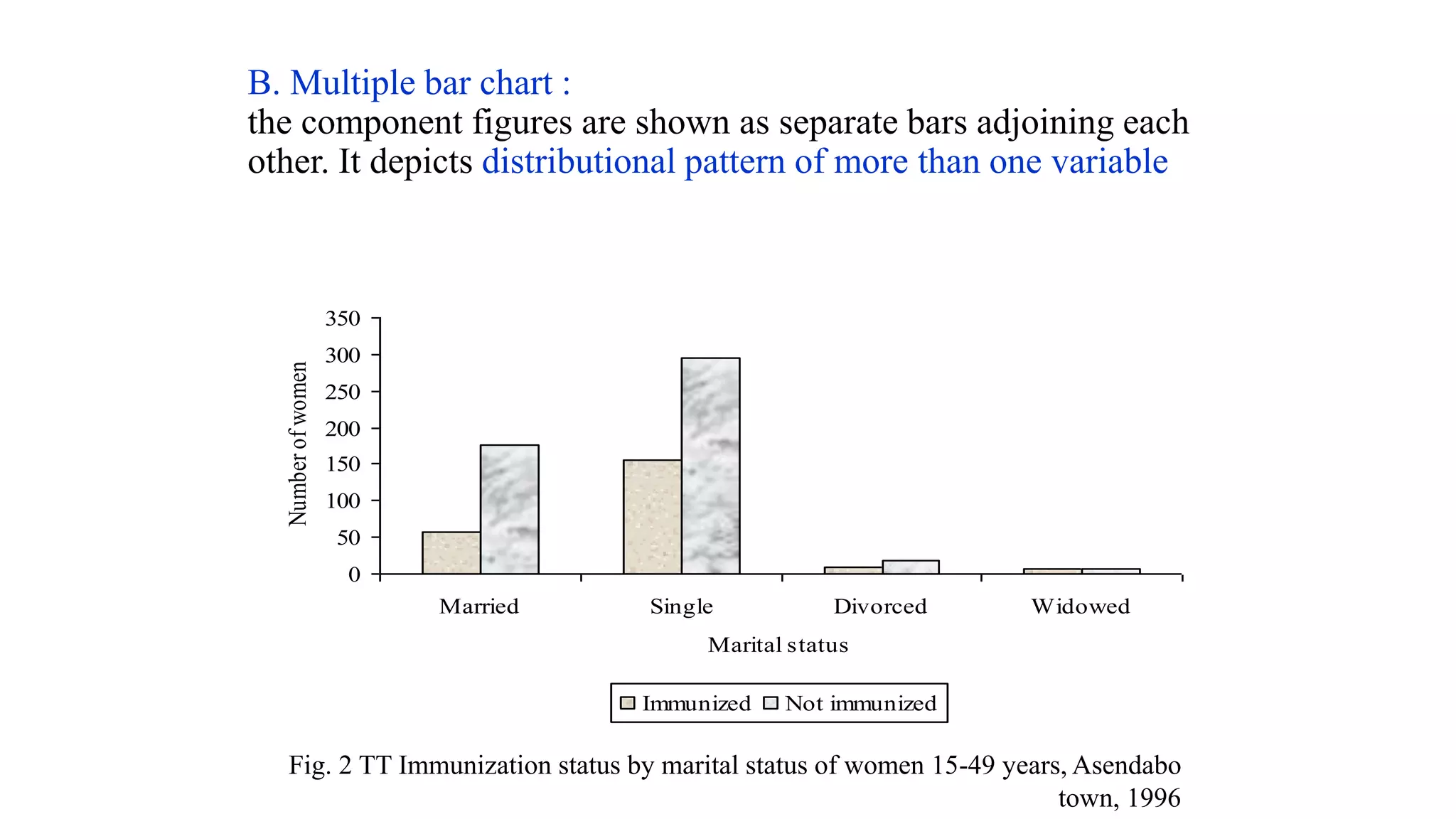

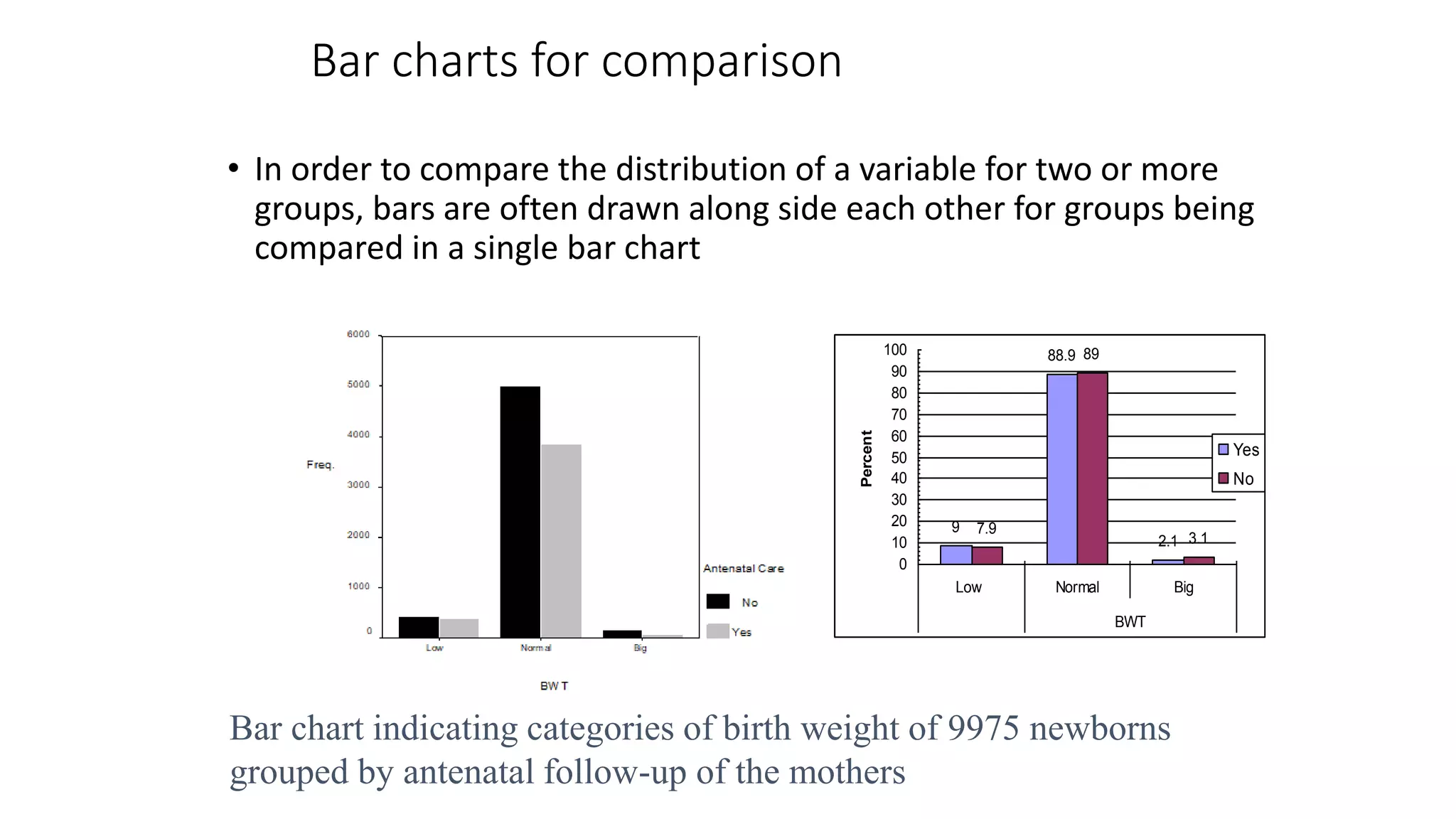

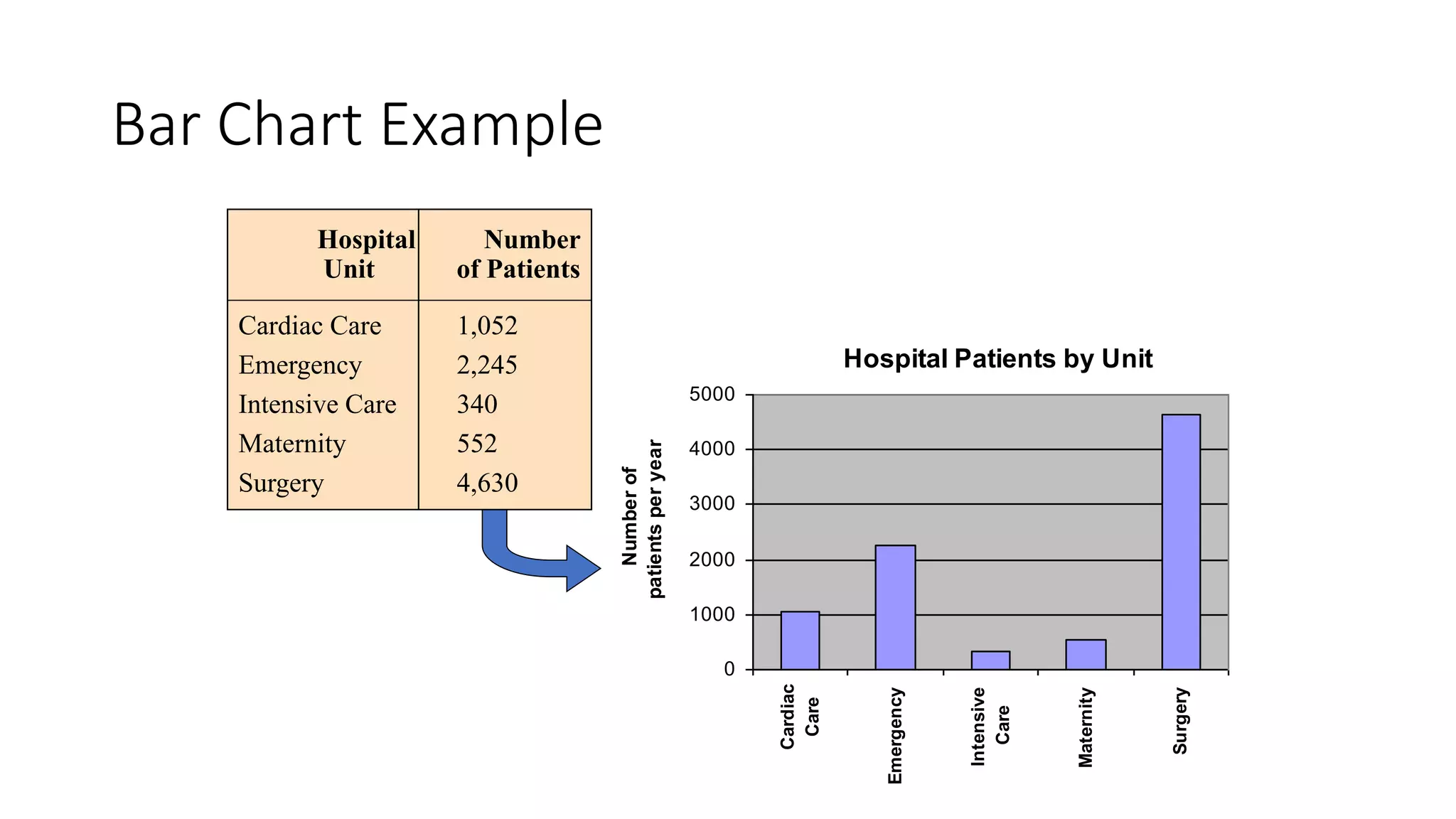

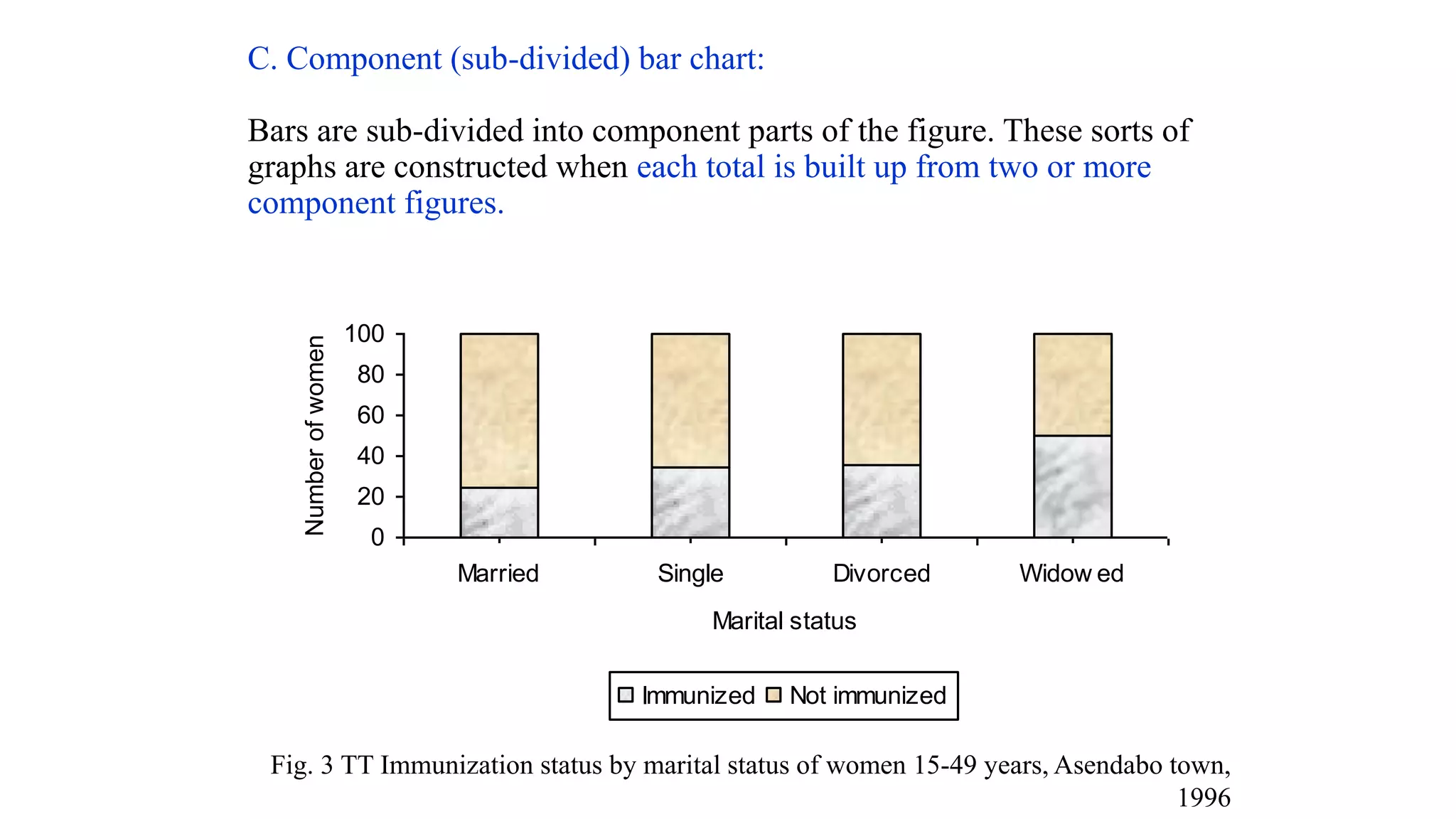

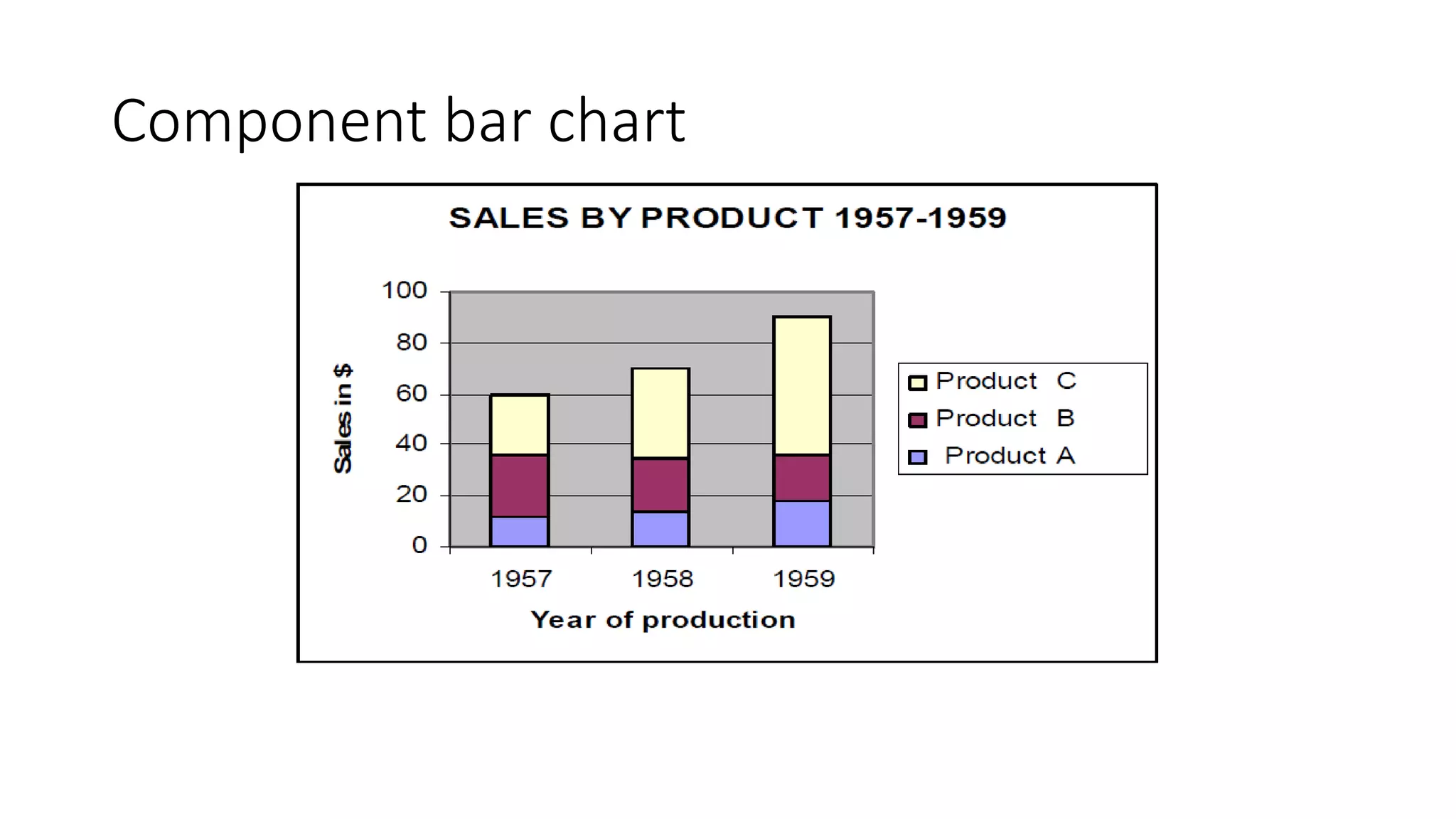

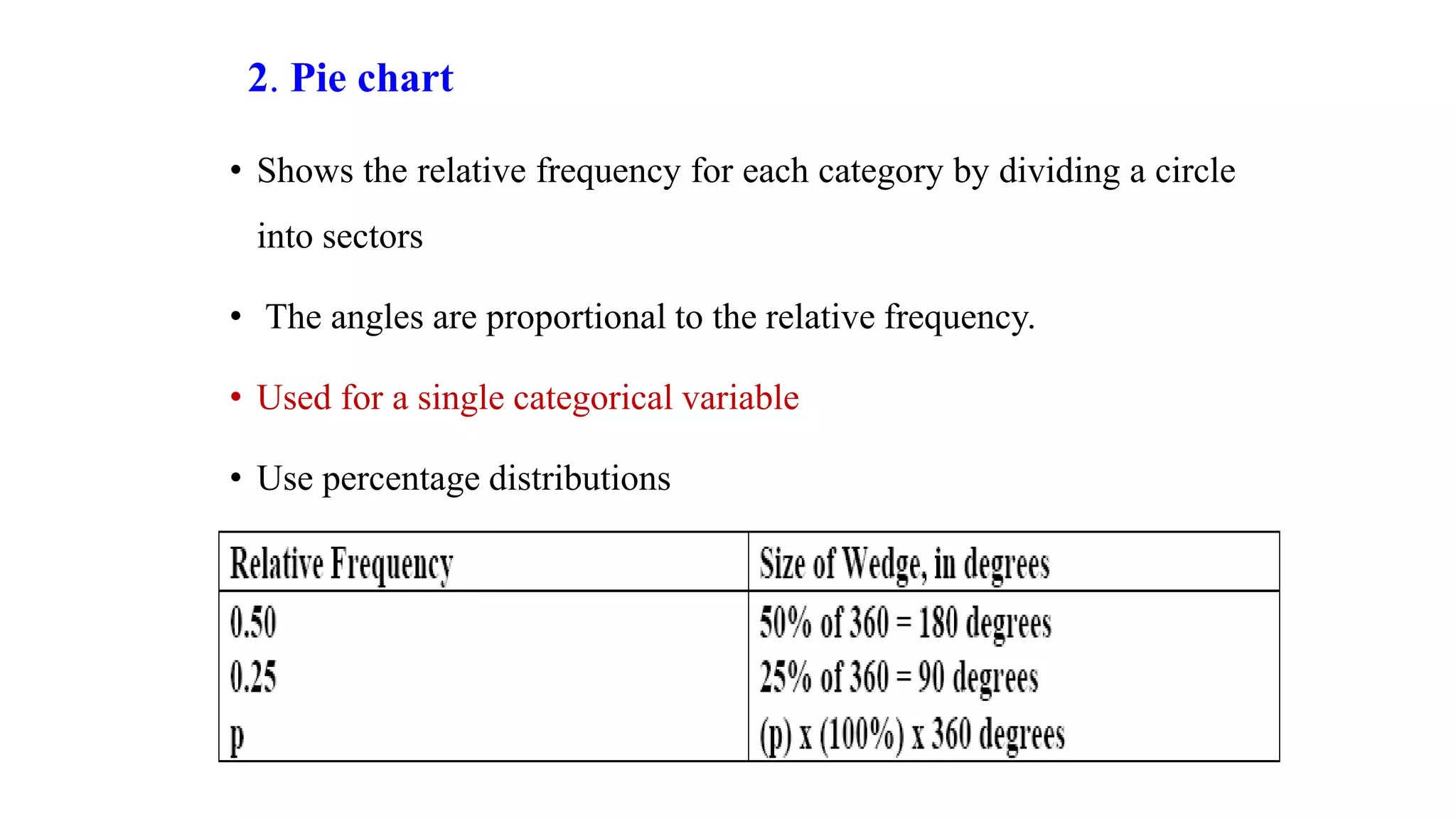

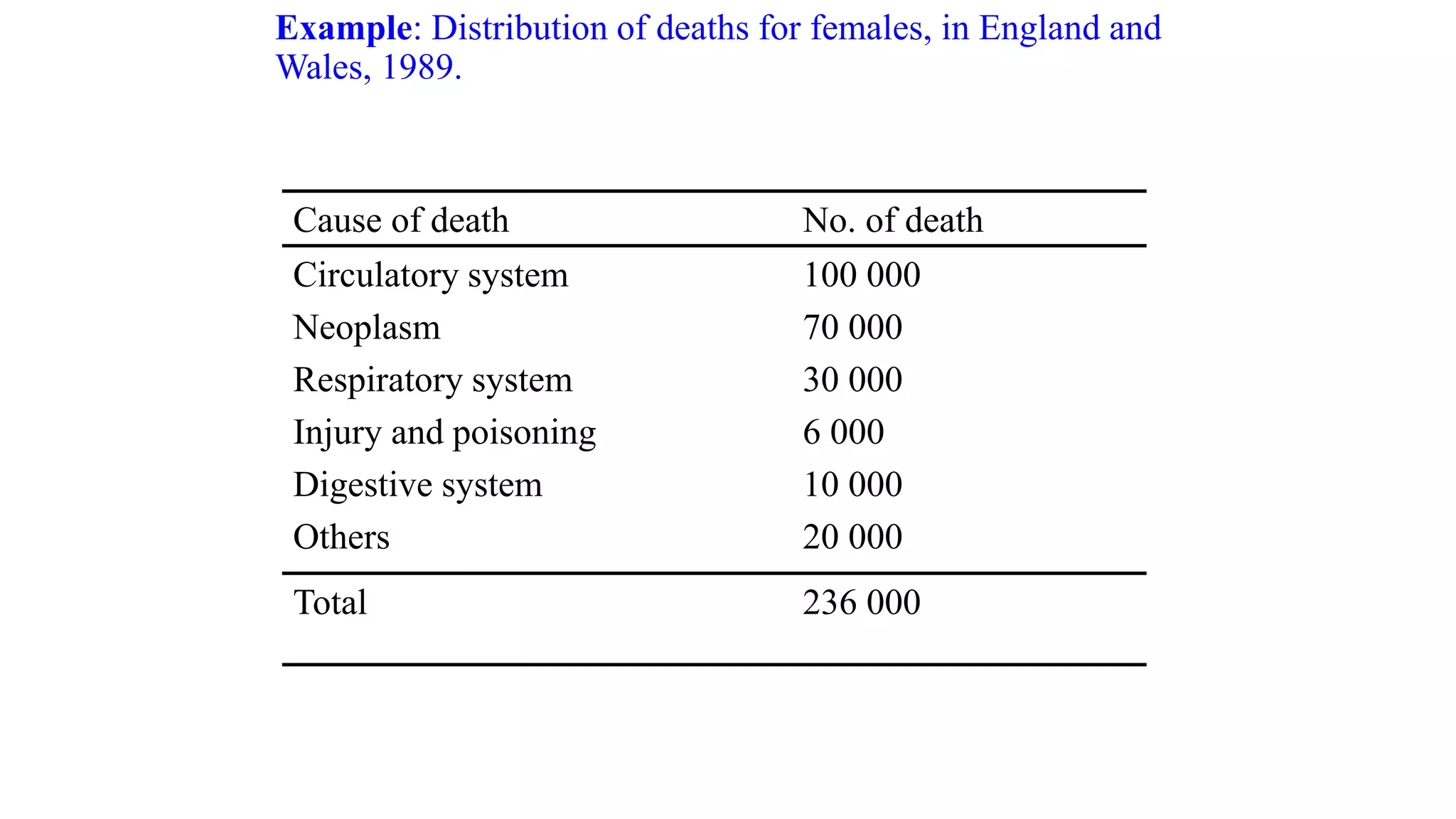

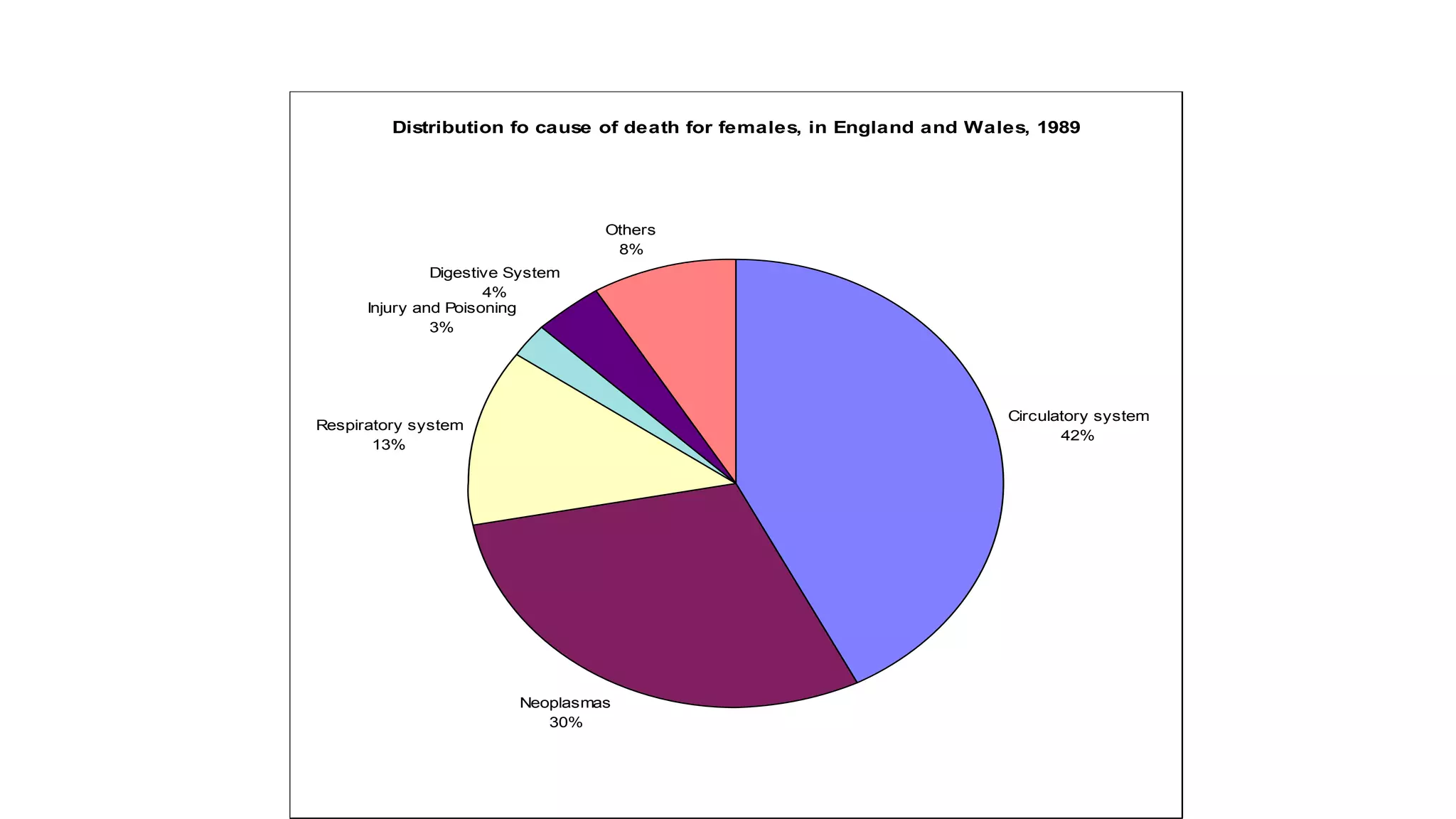

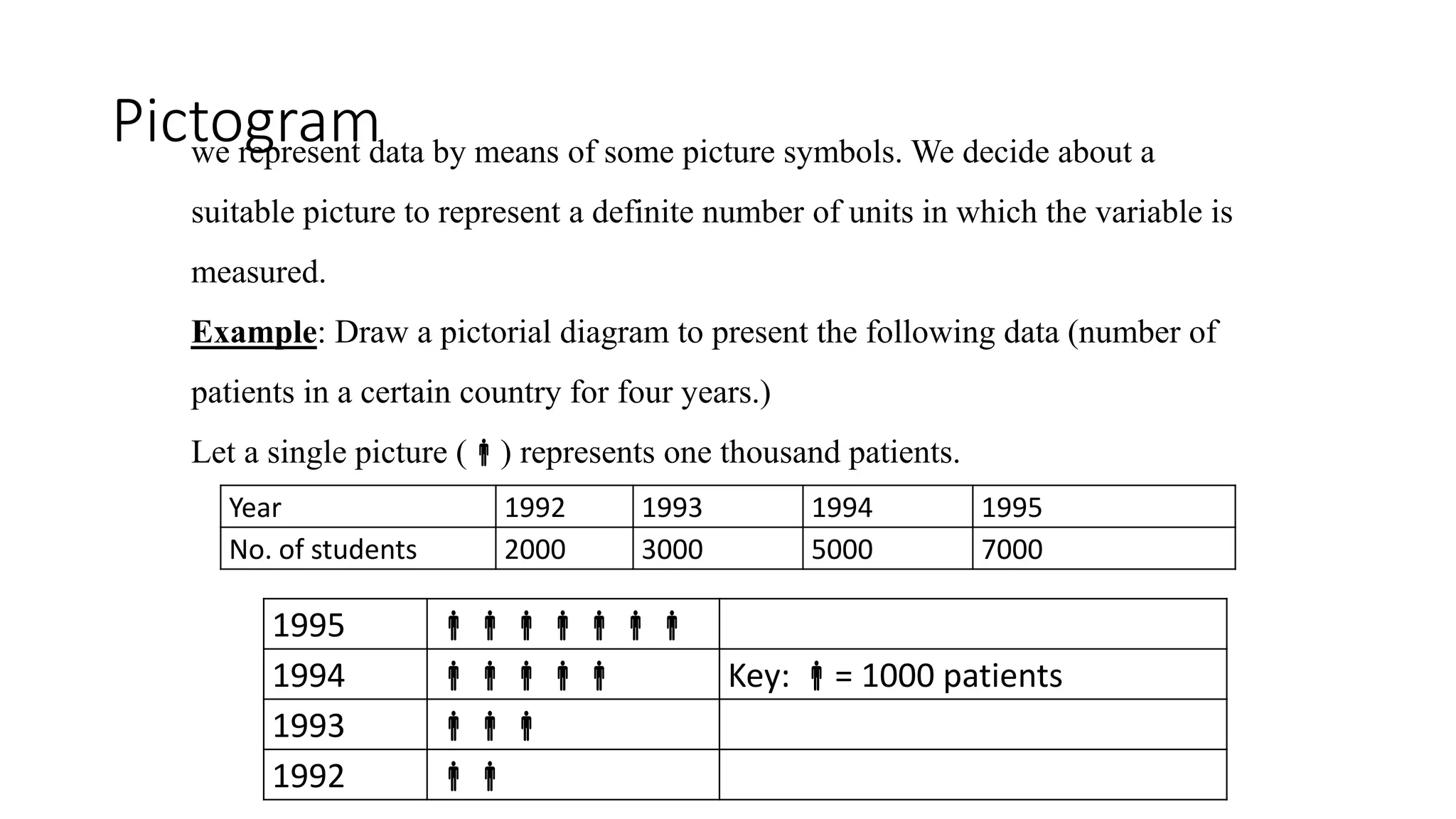

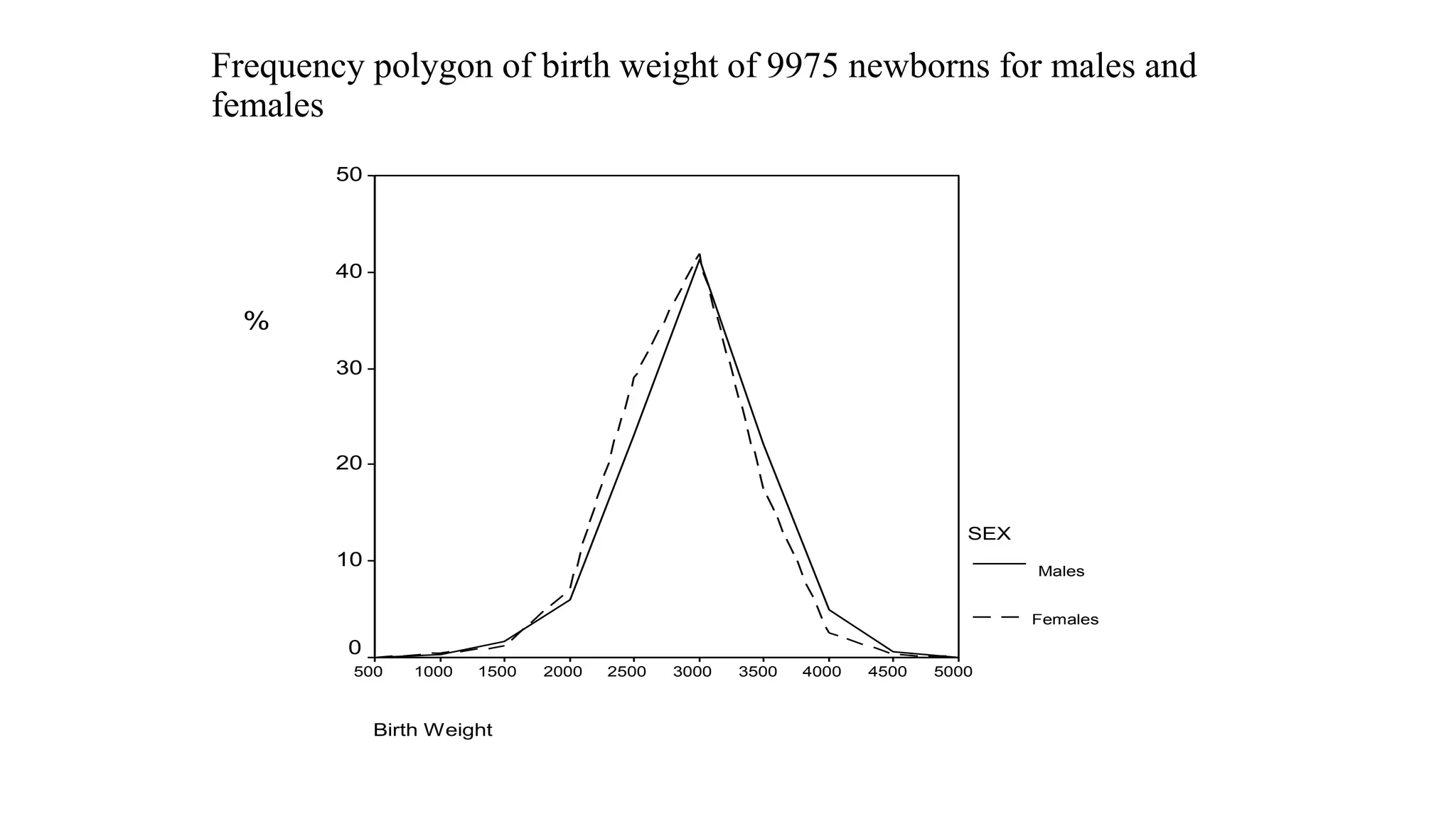

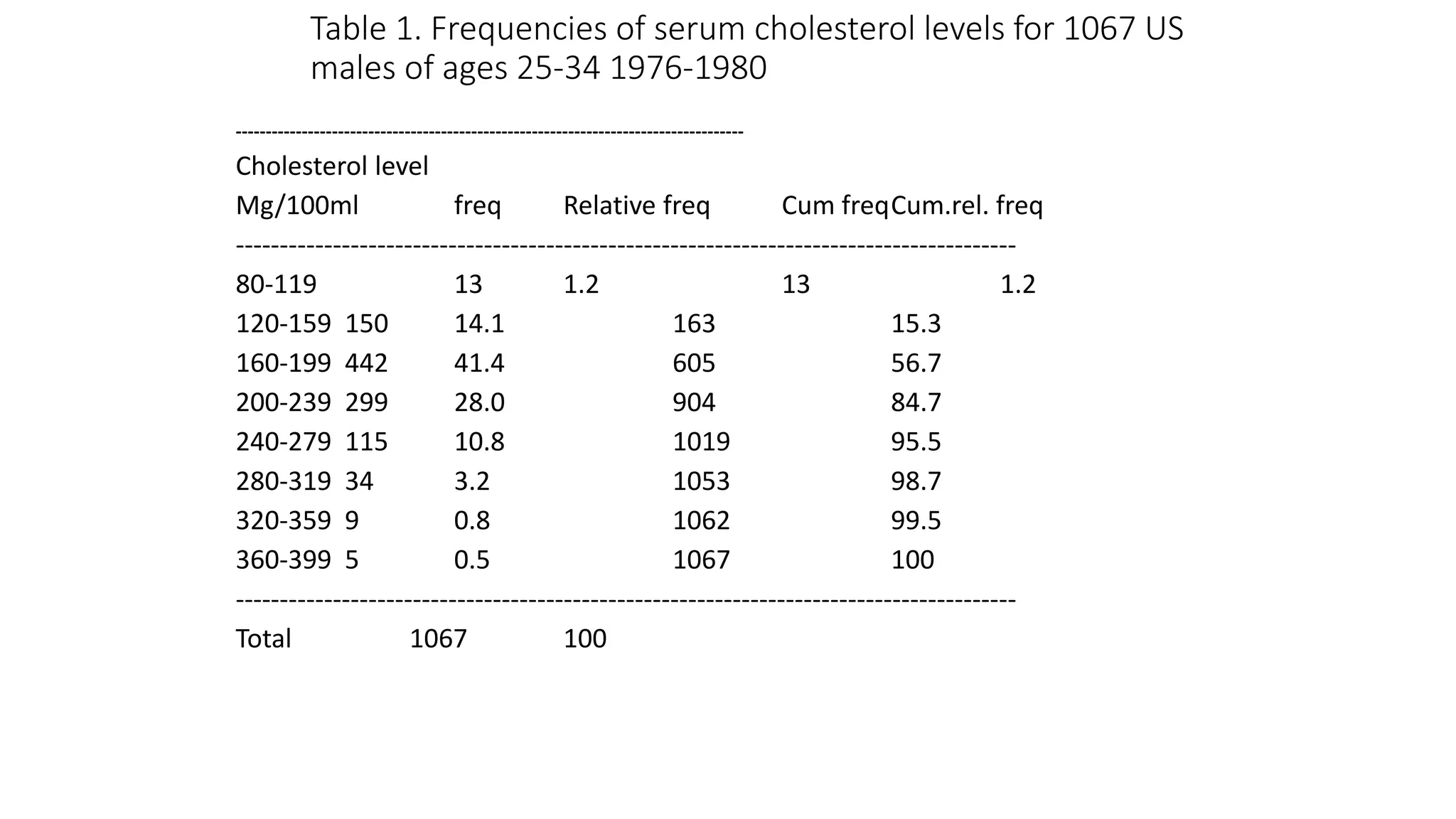

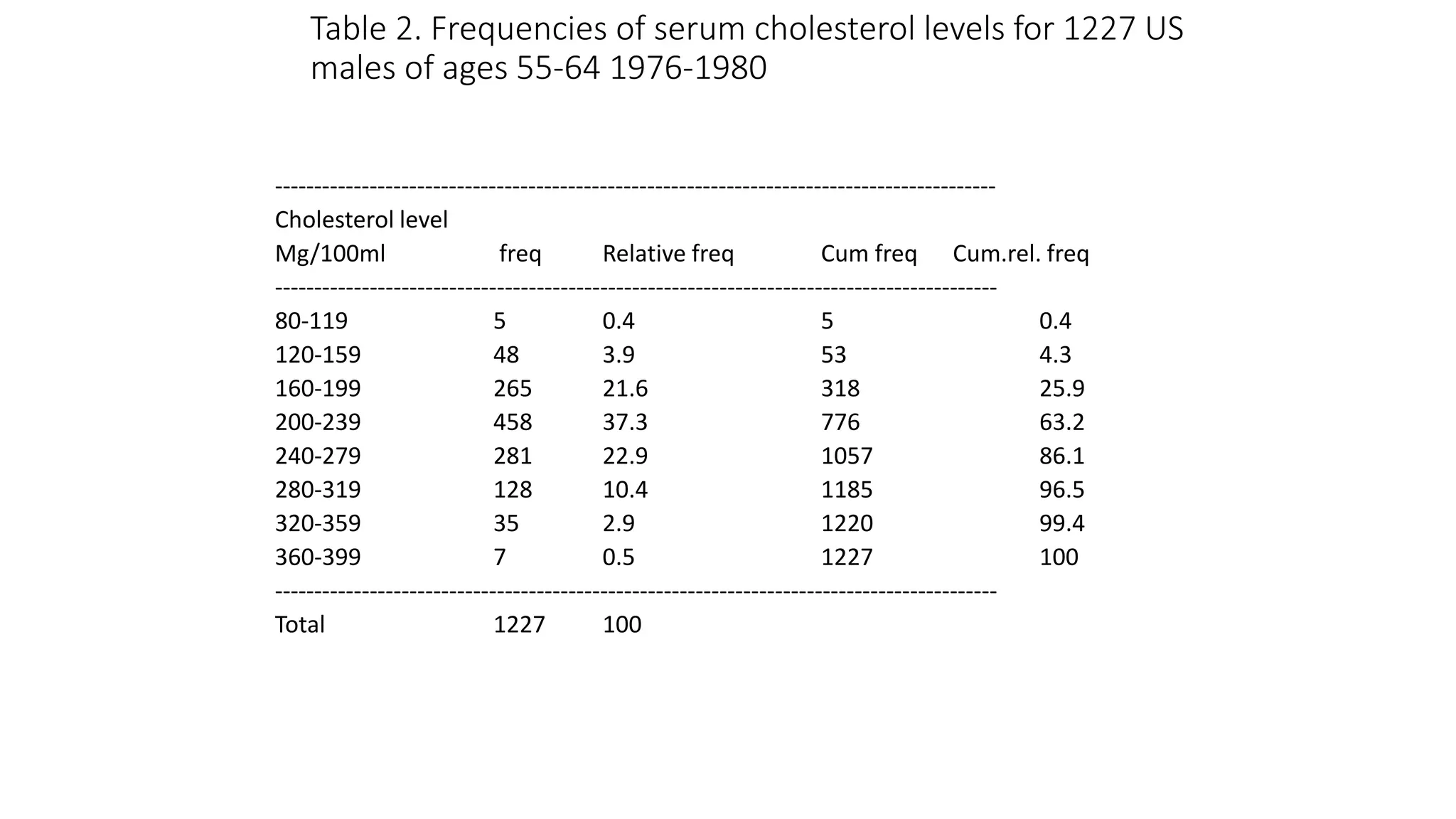

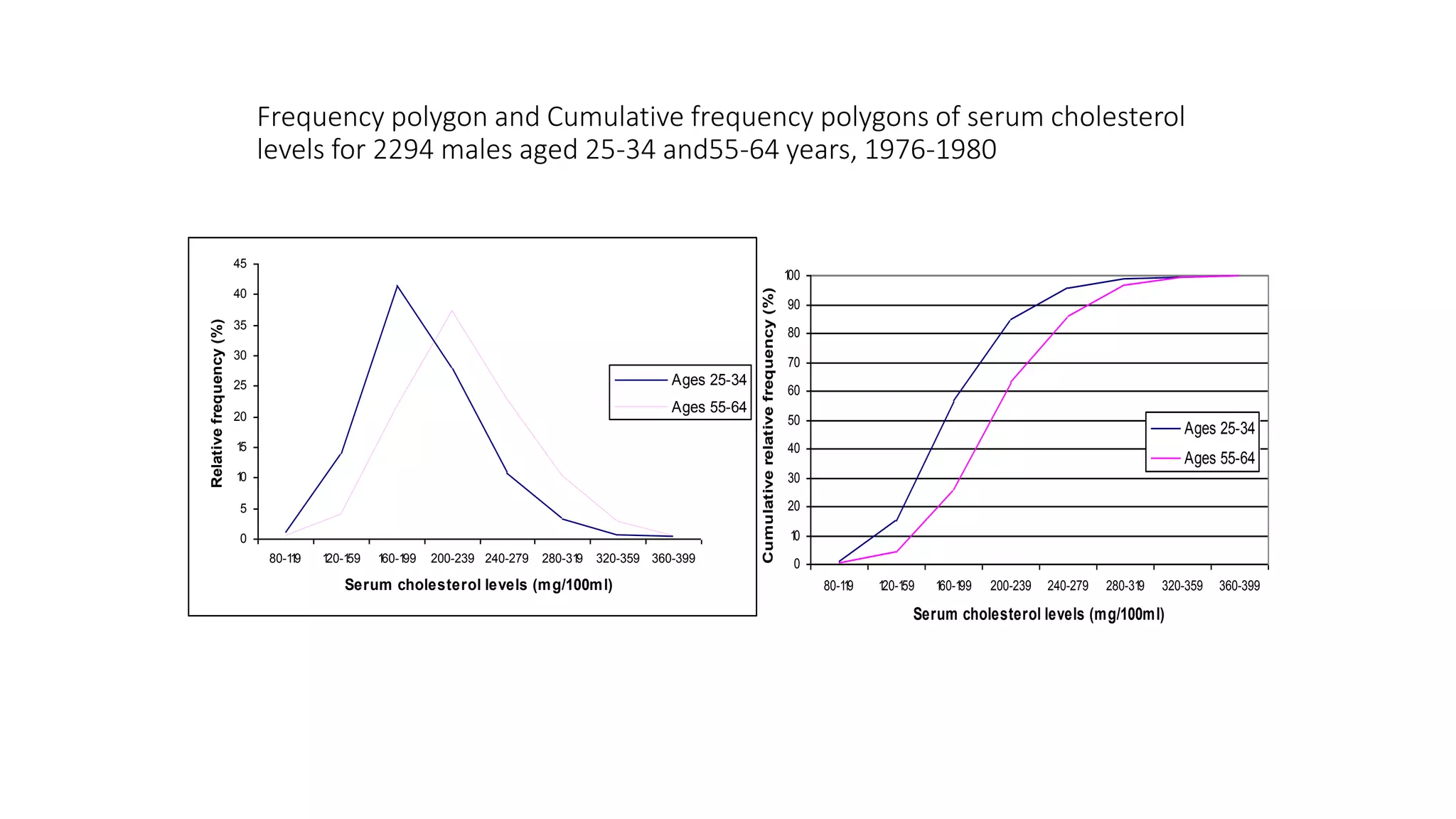

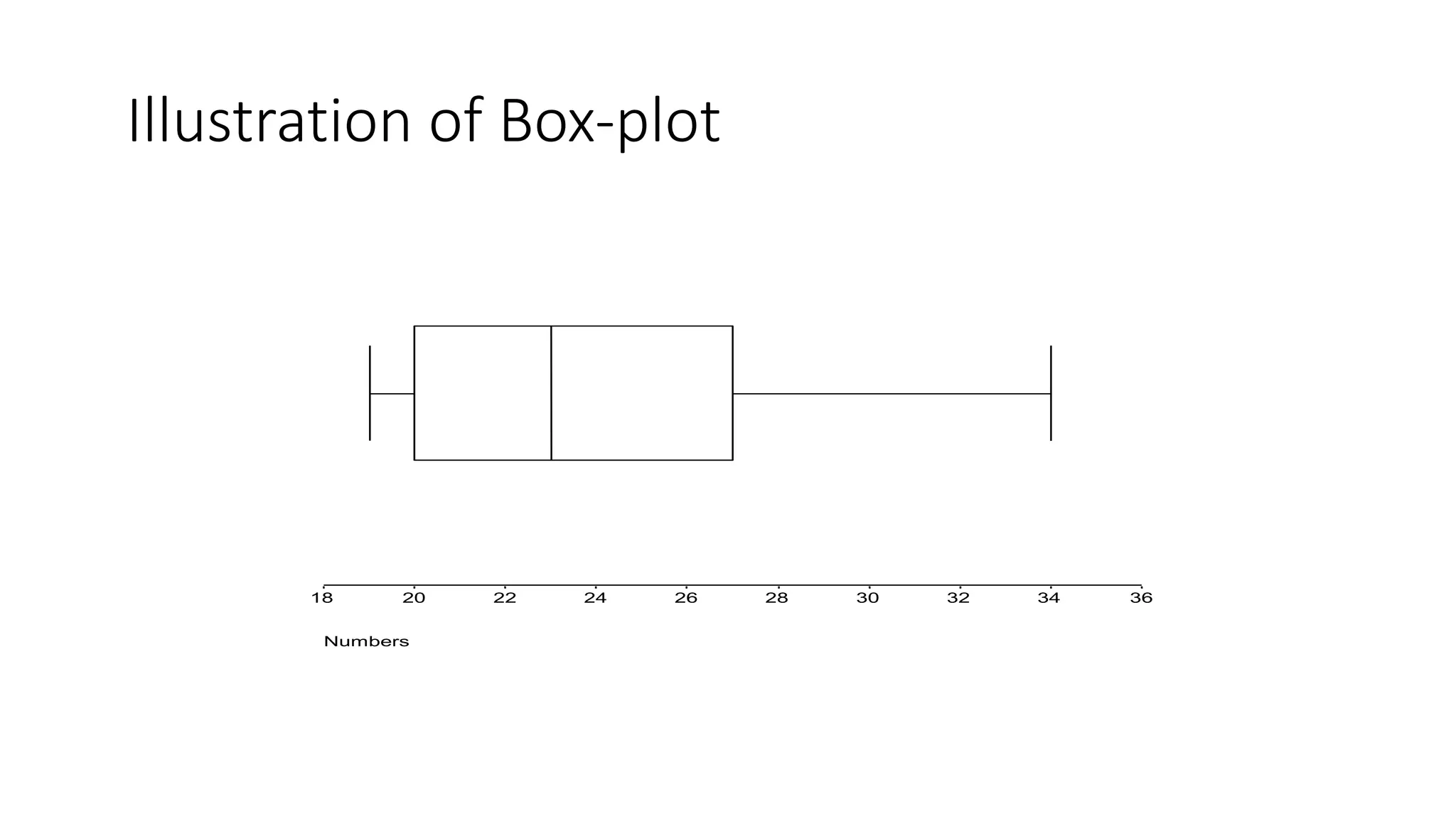

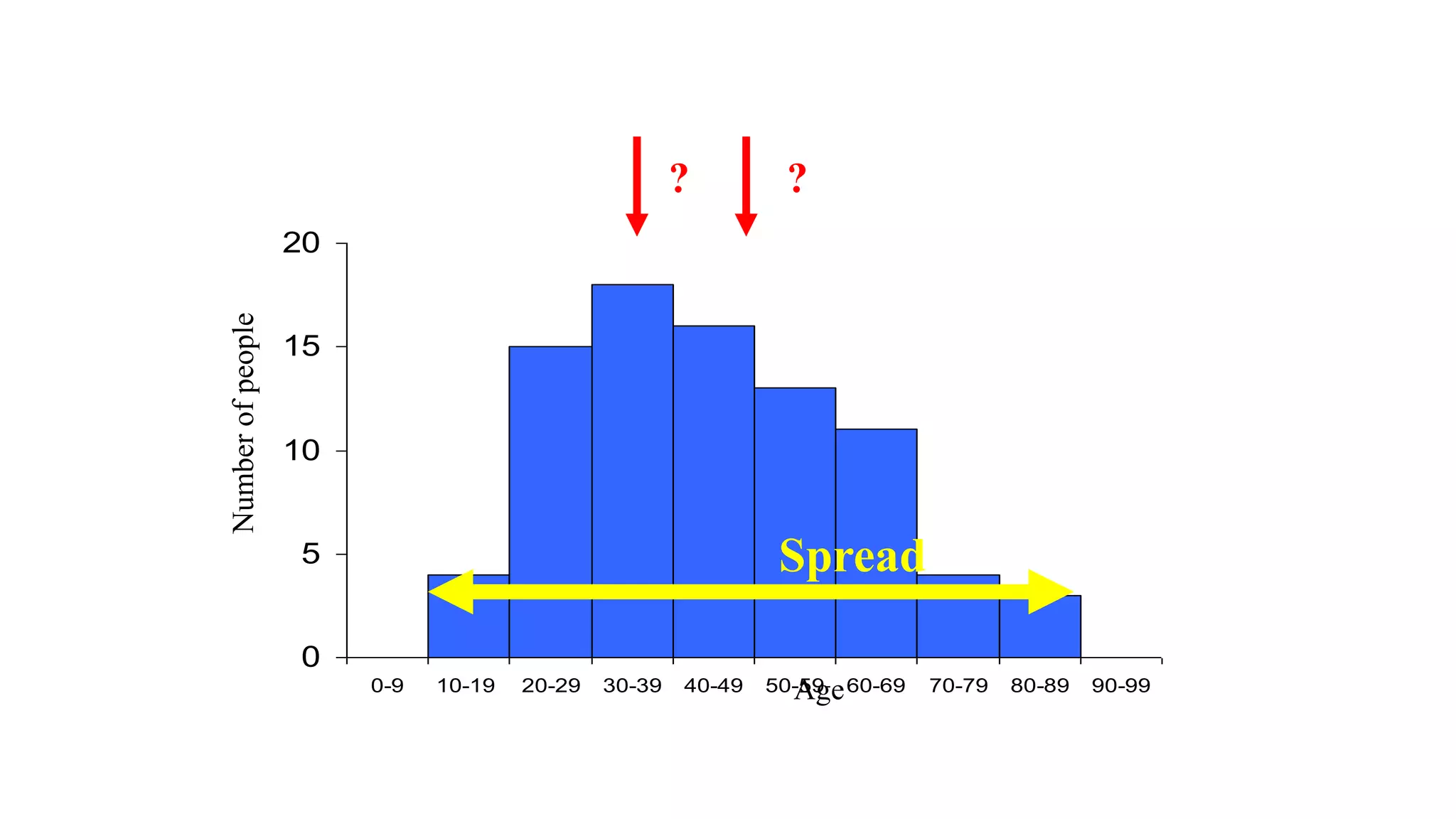

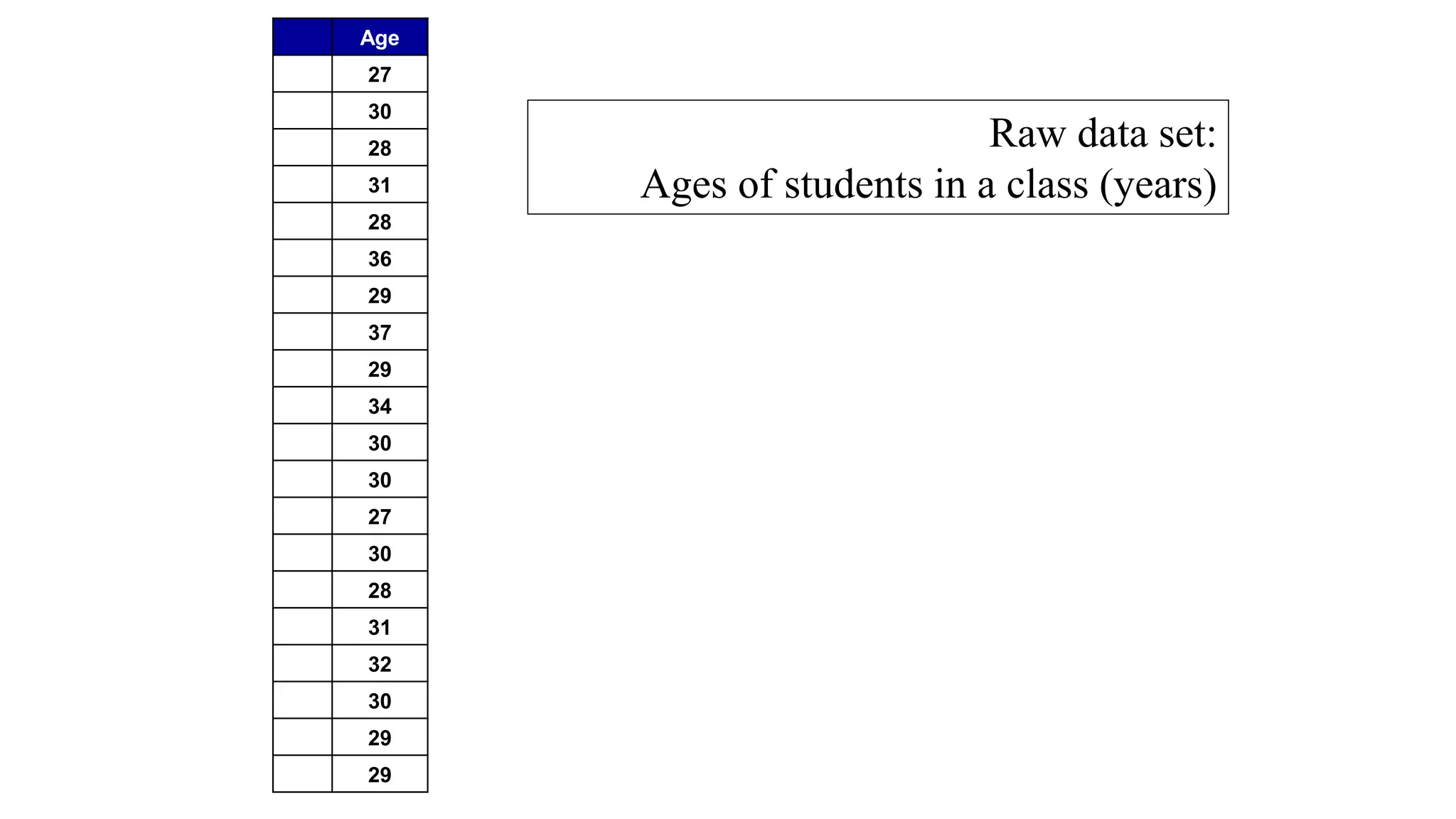

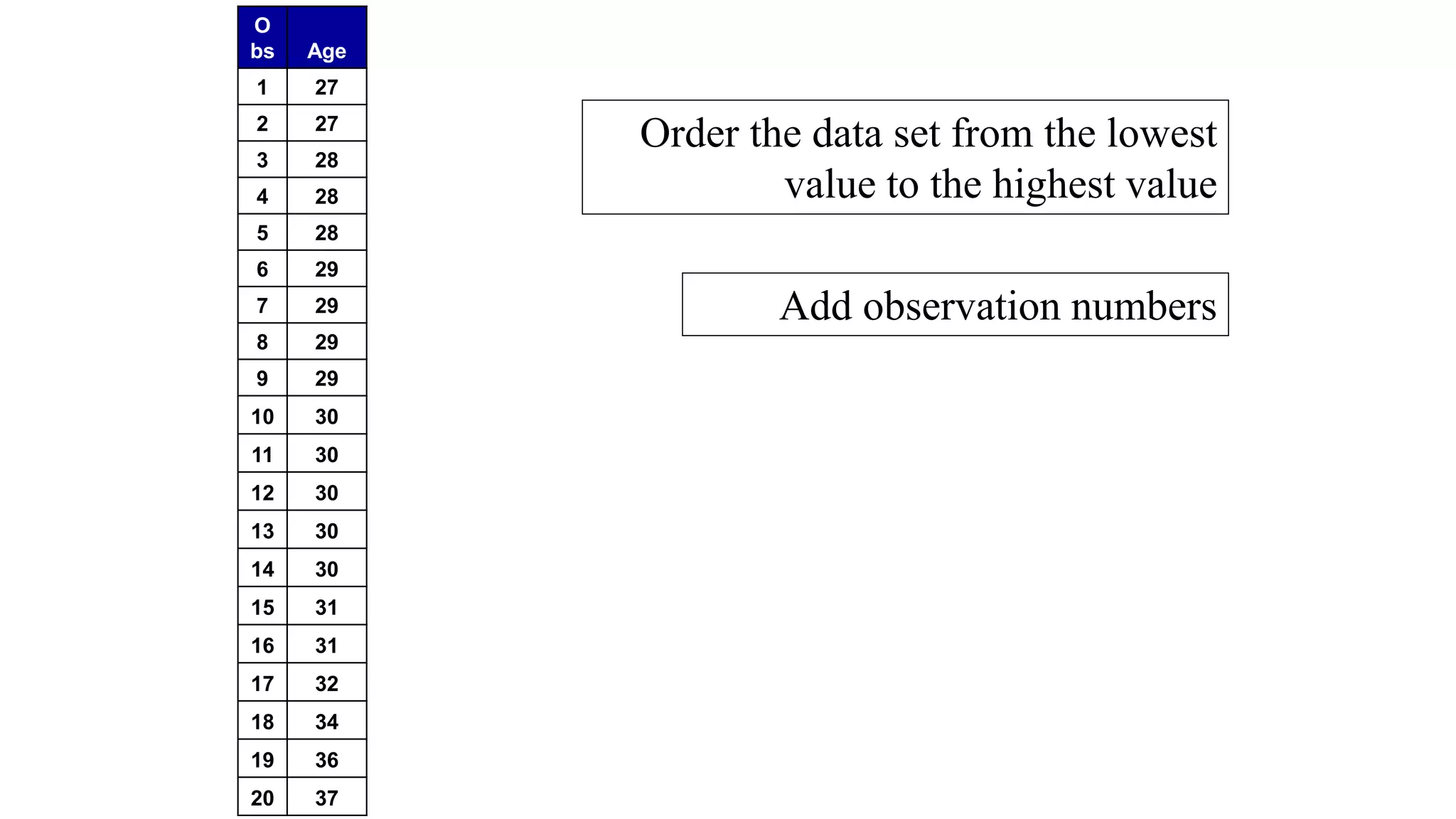

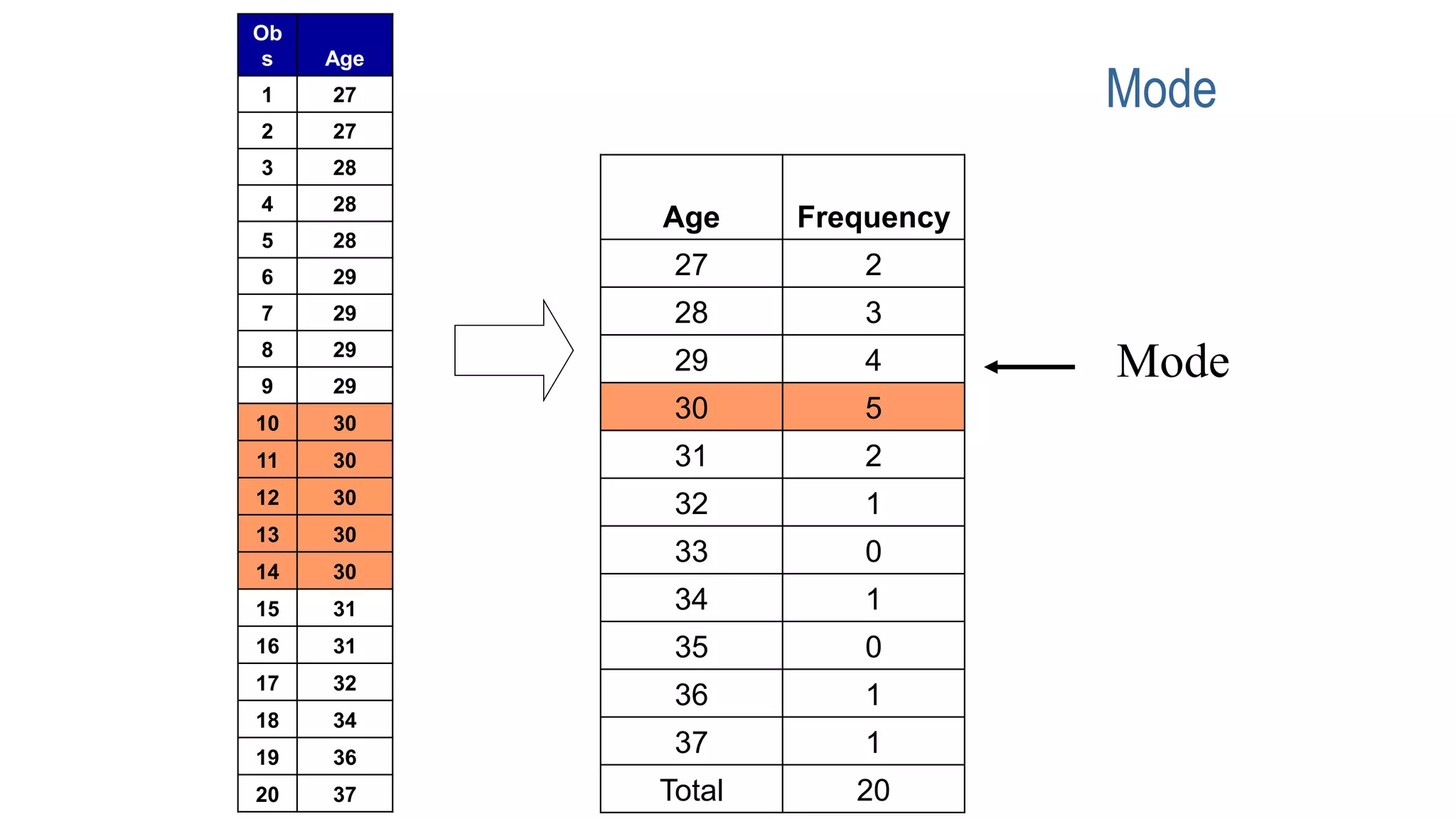

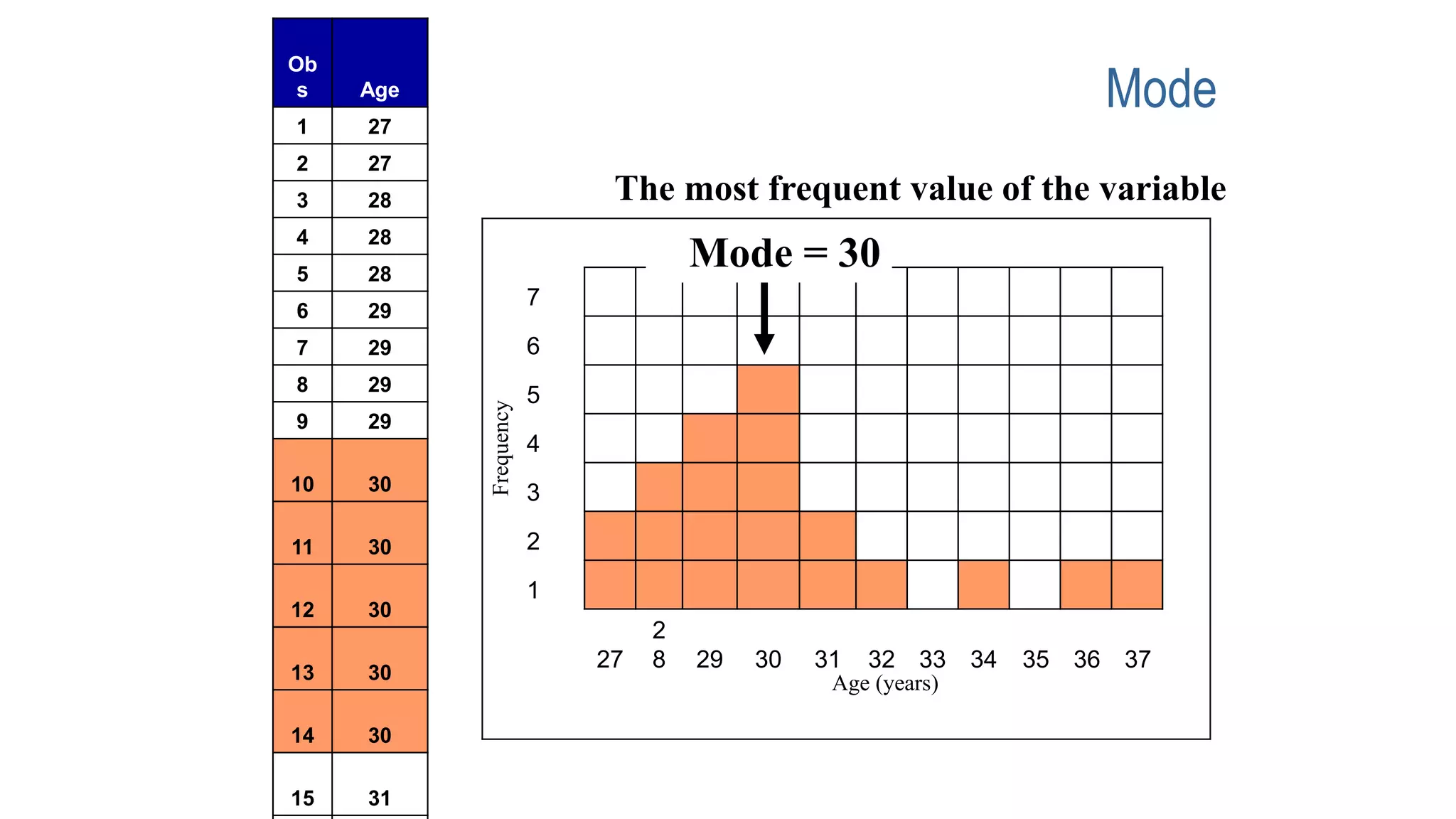

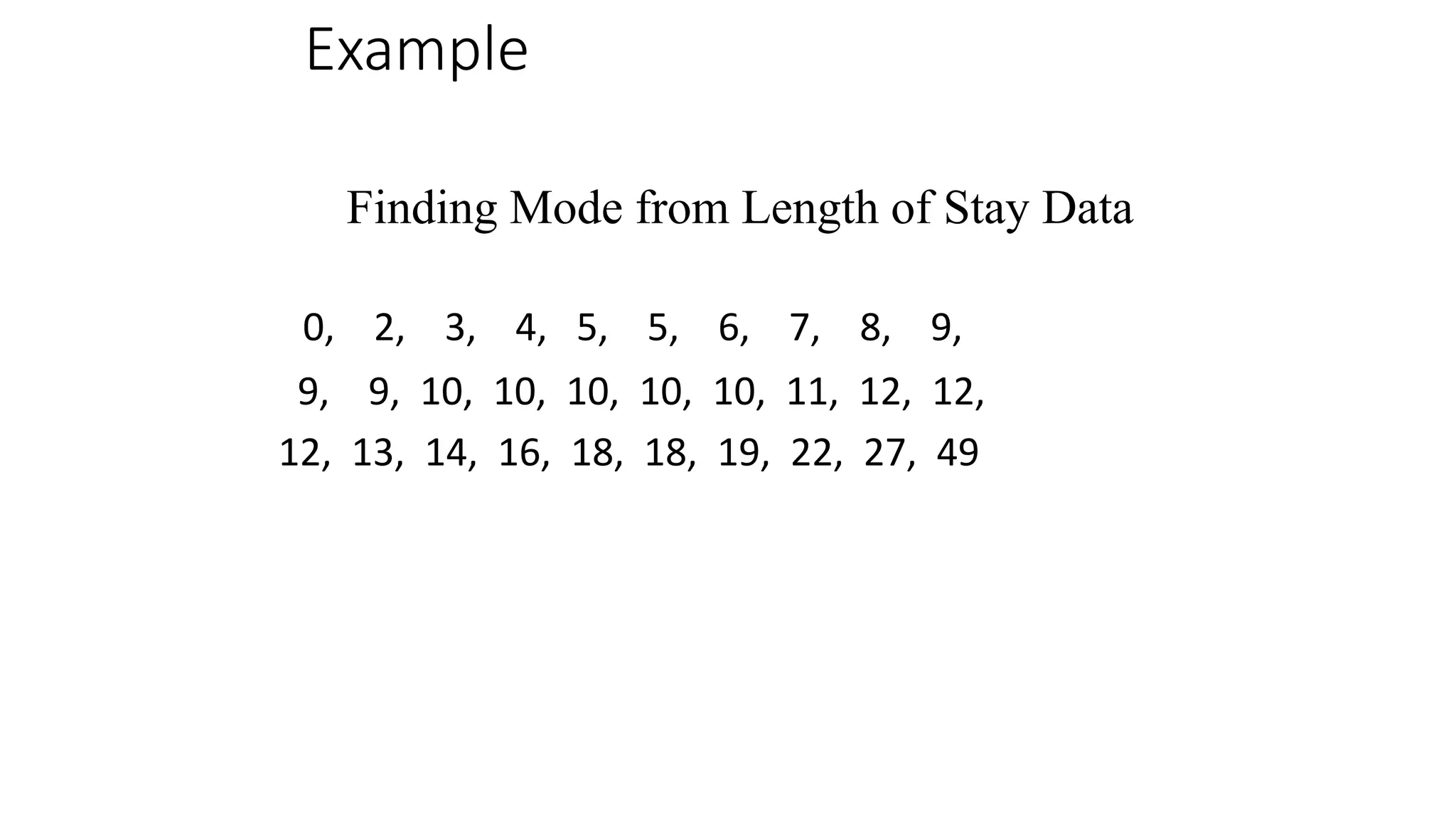

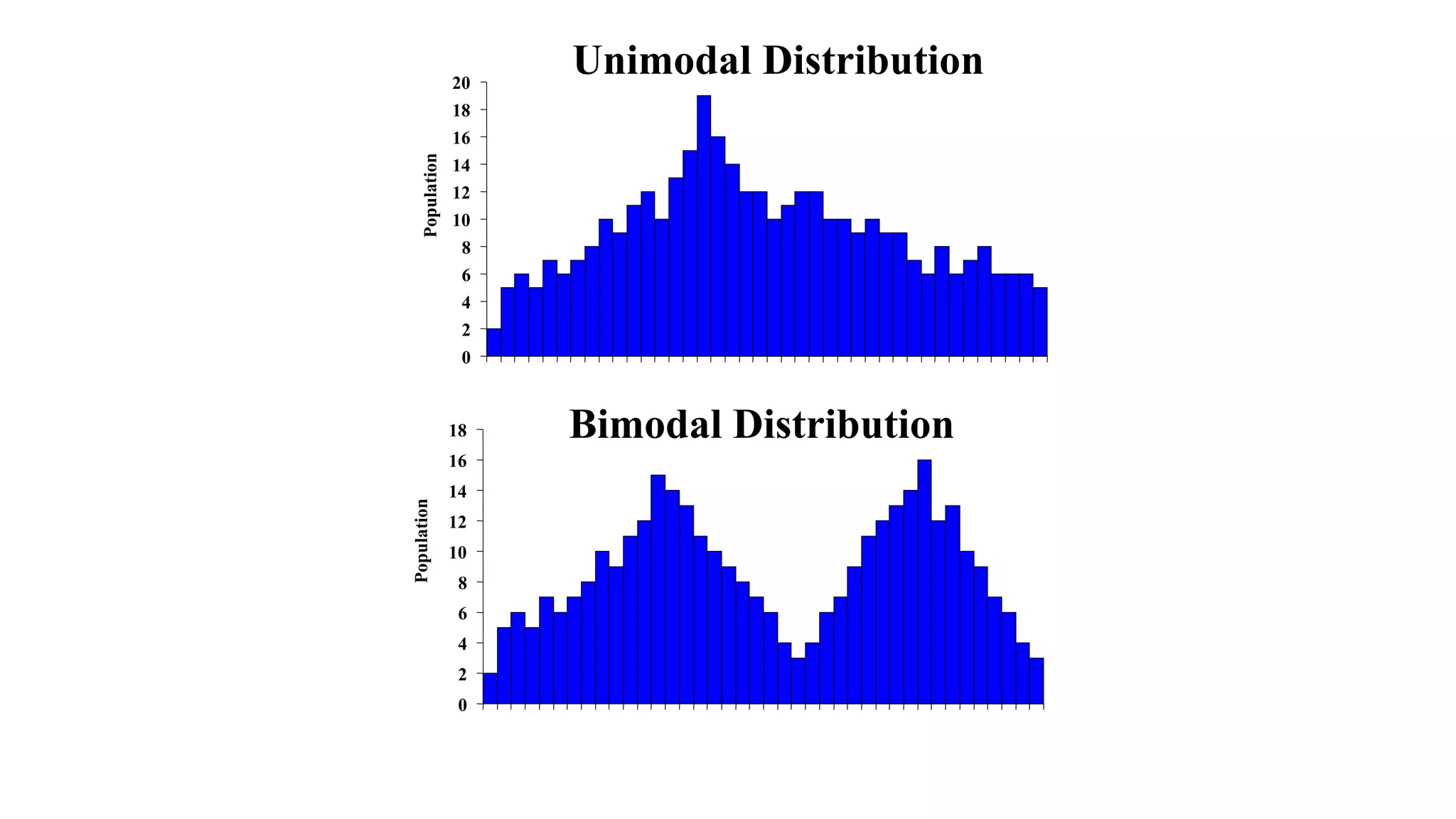

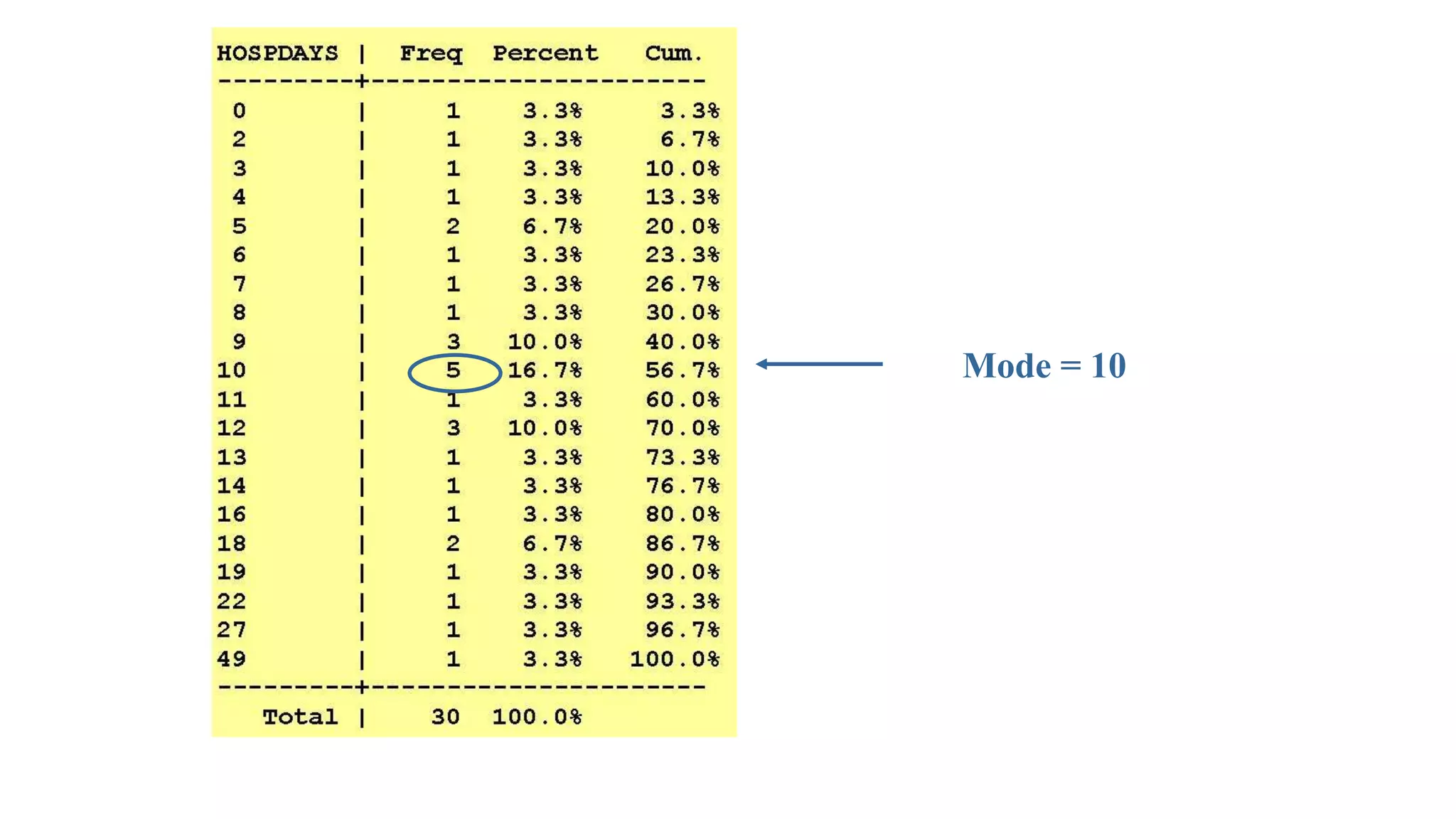

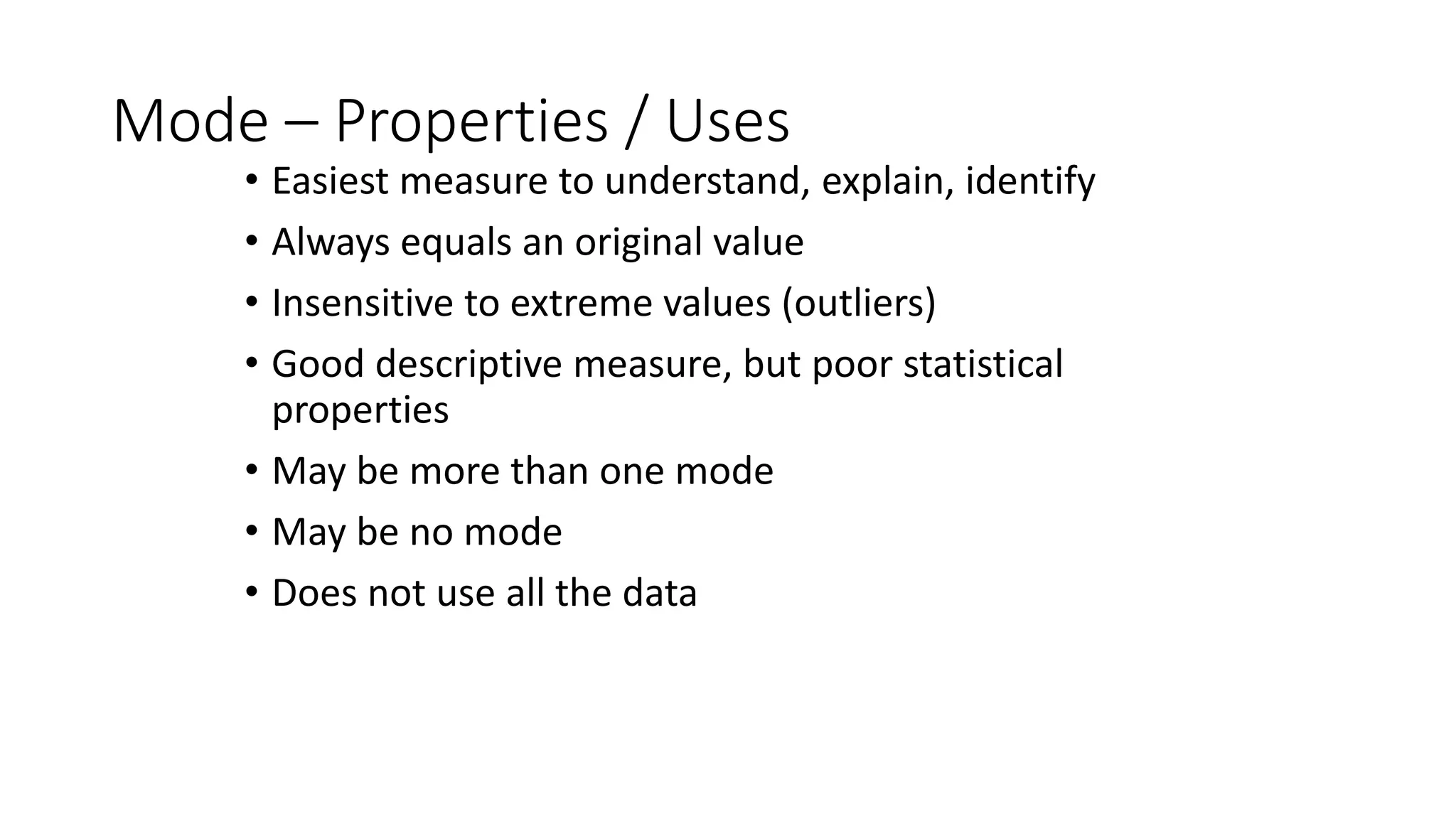

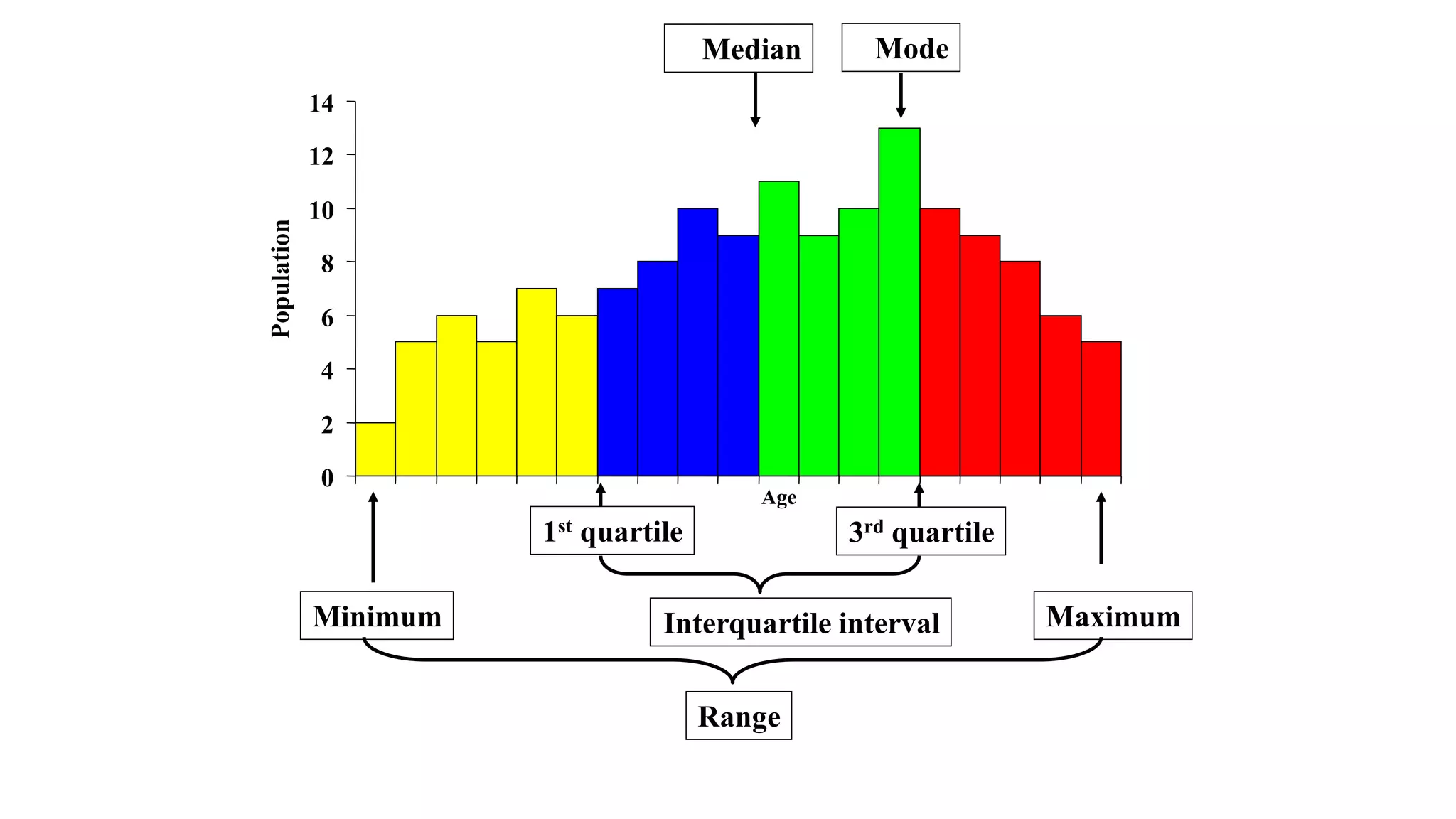

This document discusses various methods for summarizing and presenting data, including frequency distributions, diagrams, charts, and graphs. It provides guidelines for constructing tables and describes different types of frequency distributions like grouped and ungrouped. Common charts covered are bar charts, pie charts, histograms, and pictograms. It also discusses relative frequency, cumulative frequency and how to represent these graphically using techniques like frequency polygons and ogives.