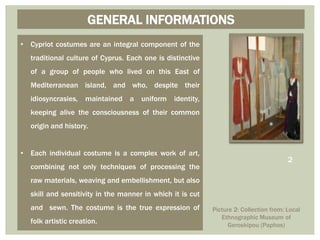

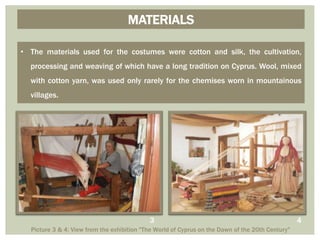

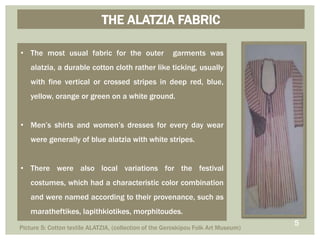

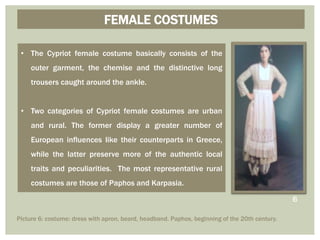

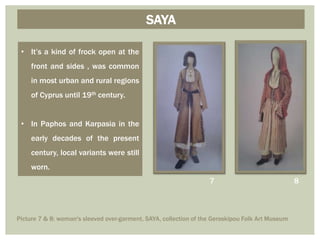

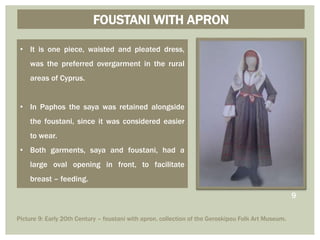

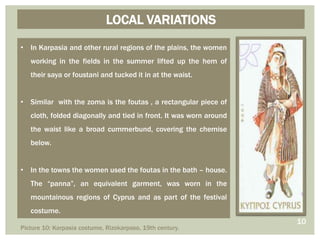

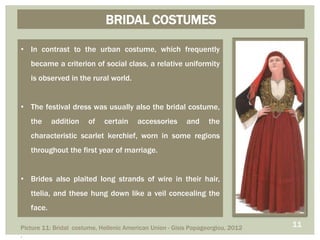

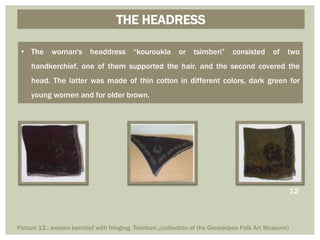

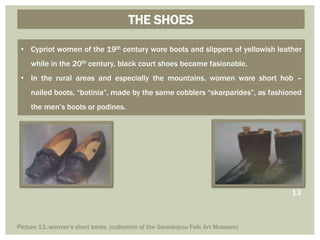

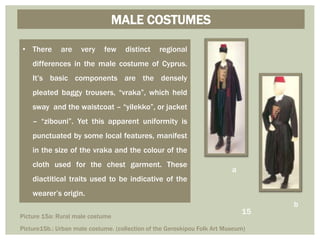

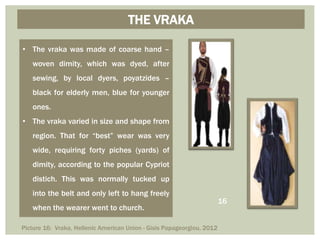

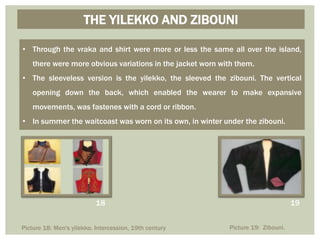

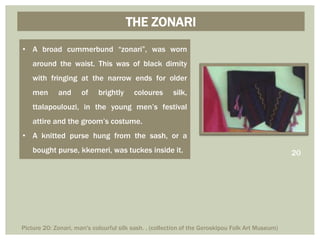

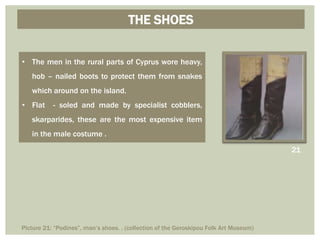

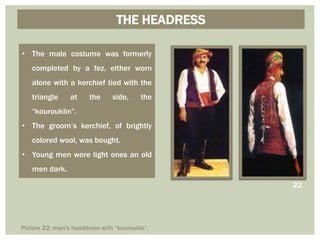

The document provides information on traditional Cypriot costumes from various regions of Cyprus. It describes in detail the typical elements of male and female costumes, including the materials used, pieces of clothing, accessories, and some regional variations. The female costume generally consisted of an outer garment, chemise, and long trousers, with the main outer garments being the saya, foustani, and saya. The male costume was characterized by baggy pleated trousers called vraka, along with a waistcoat or jacket. Accessories for both included head coverings, jewelry, and footwear. The costumes reflected the local traditions and identities of the island's communities while also incorporating some European influences over time.