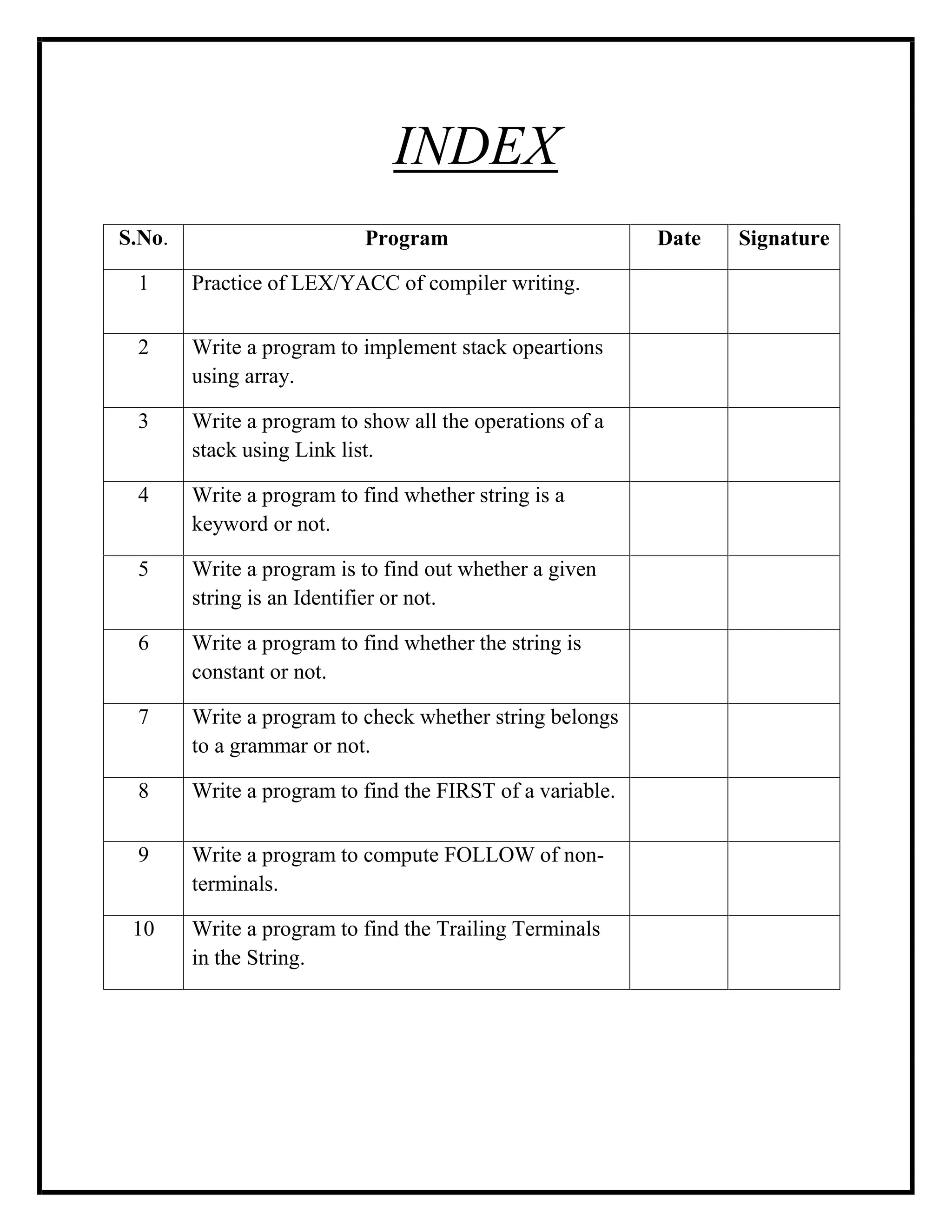

The document discusses compiler theory and provides code examples. It covers:

1. Lex theory - how regular expressions are used to specify patterns for tokenization and how these are implemented as finite state automata.

2. Yacc theory - how context-free grammars are specified in BNF and parsed using shift-reduce parsing. Issues like shift-reduce conflicts and reduce-reduce conflicts are explained.

3. Code examples of stack implementations using arrays and linked lists, and a program to check if a string is a keyword.

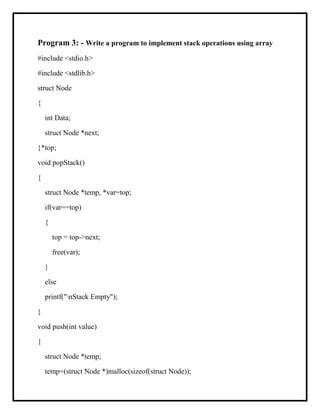

![Program 2: - Write a program to implement stack operations using an

array.

#define MAX 4 //you can take any number to limit your stack size

#include<stdio.h>

#include<conio.h>

int stack[MAX];

int top;

void push(int token)

{

char a;

do

{

if(top==MAX-1)

{

printf("Stack full");

return;

}

printf("nEnter the token to be inserted:");

scanf("%d",&token);

top=top+1;

stack[top]=token;

printf("do you want to continue insertion Y/N");

a=getch();](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-7-320.jpg)

![}

while(a=='y');

}

int pop()

{

int t;

if(top==-1)

{

printf("Stack empty");

return -1;

}

t=stack[top];

top=top-1;

return t;

}

void show()

{

int i;

printf("nThe Stack elements are:");

for(i=0;i<=top;i++)

{

printf("%d",stack[i]);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-8-320.jpg)

![printf("n");

}

else

printf("nStack is Empty");

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int i=0;

top=NULL;

printf(" n1. Push to stack");

printf(" n2. Pop from Stack");

printf(" n3. Display data of Stack");

printf(" n4. Exitn");

while(1)

{

printf(" nChoose Option: ");

scanf("%d",&i);

switch(i)

{

case 1:

{

int value;

printf("nEnter a valueber to push into Stack: ");](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-14-320.jpg)

![Program 4:- Program to find whether string is a keyword or not.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<conio.h>

#include<string.h>

void main()

{

int i,flag=0,m;

char s[5][10]={"if","else","goto","continue","return"},st[10];

clrscr();

printf("n enter the string :");

gets(st);

for(i=0;i<5;i++)

{

m=strcmp(st,s[i]);

if(m==0)

flag=1;

}

if(flag==0)

printf("n it is not a keyword");

else

printf("n it is a keyword");

getch();

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-17-320.jpg)

![Program 5:- Write a program is to find out whether a given string is a

Identifier or not.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<conio.h>

#include<string.h>

#include<ctype.h>

void main()

{

int i=0,flag=0;

char string[10];

clrscr();

printf("Enter a string :");

gets(string);

/*----Checking the 1st character*----*/

if((string[0]=='_')||(isalpha(string[0])!=0))

{

/*---Checking rest of the characters*---*/

for(i=1;string[i]!='0';i++)

if((isalnum(string[i])==0)&&(string[i]!='_'))

flag=1;

}

else

flag=1;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-19-320.jpg)

![Program no.6 :- Program to find whether the string is constant or not.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<conio.h>

#include<ctype.h>

#include<string.h>

void main()

{

char str[10];

int len,a;

clrscr();

printf("n Input a string :");

gets(str);

len=strlen(str);

a=0;

while(a<len)

{

if(isdigit(str[a]))

{

a++;

}

else

{

printf(" It is not a Constant");](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-21-320.jpg)

![Program 7: Write a program to check whether string belongs to a grammar

or not.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<conio.h>

#include<string.h>

void main()

{

clrscr();

int i,j,k=0;

char x,y,z;

char S[10],A[10],B[10],C[10];

printf("t Enter String S->");

gets(S);

for(i=0;i<=strlen(S)-1;i=i+1)

{

x=S[i];

z=S[i+1];

if(x>='a' && x<='z')

{

printf("n n t First(S)-> %c",x);

break;

}

else](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-23-320.jpg)

![{

printf("n n t Enter String for %c-> ",x);

label1:

gets(C);

for(j=0;j<=strlen(C)-1;j++)

{

y=C[j];

if(y>='a' && y<='z')

goto label;

else

{

printf("nt Enter String For %c-> ",y);

goto label1;

}

}

}

}

label:

printf("ntFirst(S)->%c%c",y,z);

getch();

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-24-320.jpg)

![Program 8: Write a program to find the FIRST of a variable.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<conio.h>

#include<string.h>

void main()

{

clrscr();

int i,j,k=0;

char x,y,z;

char S[10],A[10],B[10],C[10];

printf("t Enter String S->");

gets(S);

for(i=0;i<=strlen(S)-1;i=i+1)

{

x=S[i];

z=S[i+1];

if(x>='a' && x<='z')

{

printf("n n t First(S)-> %c",x);

break;

}

else](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-26-320.jpg)

![{

printf("n n t Enter String for %c-> ",x);

label1:

gets(C);

for(j=0;j<=strlen(C)-1;j++)

{

y=C[j];

if(y>='a' && y<='z')

goto label;

else

{

printf("nt Enter String For %c-> ",y);

goto label1;

}

}

}

}

label:

printf("ntFirst(S)->%c%c",y,z);

getch();

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-27-320.jpg)

![Program 9: Write a program to find the FOLLOW of a variable.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<conio.h>

#include<math.h>

void first(char ch);

char p[10][10]={"S->aAB","A->Bc","B->d"};

char stk[10];

int top=-1;

int c=0;

int follow(char ch)

{

int i,j,c1,count=0,x;

if(ch=='S')

{

printf("$");

//break;

}

for(i=0;i<3;i++)

{

if(ch==p[i][0])

count++;

for(j=3;p[i][j]!='0';j++)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-29-320.jpg)

![{

if(p[i][j]==ch && p[i][j+1]!='0')

{

if(p[i][j+1]=='a' || p[i][j+1]=='c' || p[i][j+1]=='d')

printf(",%c",p[i][j+1]);

else

first(p[i][j+1]);

}

if(p[i][j]==ch && p[i][j+1]=='0')

x=follow(p[i][0]);

}

}

return count;

}

void first(char ch)

{ int i;

for(i=0;i<3;i++)

{

if(ch==p[i][0])

{

if(p[i][3]=='a' || p[i][3]=='c' || p[i][3]=='d')

printf("%c",p[i][3]);

else](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-30-320.jpg)

![{

top++;

stk[top]=p[i][3];

if(p[i][3]=='B')

{

if(p[i][4]=='a' || p[i][4]=='c' ||p[i][4]=='d')

printf("%c",p[i][4]);

else

{

top++;

stk[top]=p[i][4];

}

}

}

}

}

while(top!=-1)

{

char ch1;

ch1=stk[top];

top--;

first(ch1);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-31-320.jpg)

![}

void main()

{

int i;

clrscr();

printf("Grammeris-------->S->aAB A->Bc B->d");

for(i=0;i<3;i=i+c)

{

printf("nFollow of %c is:" ,p[i][0]);

c=follow(p[i][0]);

}

getch();

}

Output:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-32-320.jpg)

![Program 10: Write a program to find the Trailing Terminals in the String.

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

#include<conio.h>

#include<string.h>

#include<iostream.h>

void main()

{

clrscr();

char str1[10],str2[10];

char x,y,z;

int i,j,k;

printf("nEnter String For finding Trailing Terminalt S-> ");

gets(str1);

for(i=strlen(str1)-1;i>=0;i--)

{

x=str1[i];

if(x>='a' && x<='z')

{

printf("nTrailing Terminal of the String t S-> %c",x);

break;

}

else](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-33-320.jpg)

![{

printf("nEnter Production for t %c-> ",x);

label1:

gets(str2);

k=strlen(str2)-1;

y=str2[k];

if(str2[k]>='a' && str2[k]<='z')

{

y=str2[k];

goto label2;

}

else

{

printf("nEnter Production for t %c-> ",y);

goto label1;

}

label2:

for(j=i-1;j>=0;j--)

{

z=str1[j];

if(z>='a' && z<='z')

goto label;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cd-150109034136-conversion-gate02/85/Compiler-Design-File-34-320.jpg)